25 years ago, in 1987, the English music scene felt debilitated by a certain, deliberate, postmodern smallness. The highly influential C86 cassette put out by the NME just months earlier set the indie tone – groups like The Wedding Present, Bogshed and pre-rave Primal Scream, dubbed the “shambling bands” by John Peel, were deliberately colourless, unambitious and low-key, retaining the provincialism of punk and post-punk but little of its energy or rage – a drizzle after the storm. The Housemartins from Hull were the pop epitome of this new dispiritedness – clever purveyors of wry, sidelong ditties. It was as if the music were beset by an inferiority complex, that new generations could aspire to be no more than pygmies mooching on the shoulders of dead giants. To reach for the sky, rather than into one’s pockets, was considered unseemly, even pretentious, the worst thing one could possibly be. No air, no grace.

This stooped cultural tendency was exacerbated by the recent introduction of the sampler. Although this new technology opened up infinite possibilities, many of which would be pursued in time, it was initially used as a filching, quoting machine – the backbeat to James Brown’s ‘Funky Drummer’ or Led Zep’s ‘When The Levee Breaks’, or the retro-stream of M.A.R.R.S’ ‘Pump Up The Volume’. The overall effect of the sampler, as deployed in 1987, wasn’t in general to undertake fresh sonic exploration but to wittily refer to the past, a halcyon, disappeared age of innocence and greatness destined to be alluded to in a new, perma-era of retro-gradism. The earnest cod-soul of the pop day, meanwhile, seemed to come in with a built-in, earnest, reproachful reminder that no modern music could possibly match the grainy greatness of Motown and 60s soul, of which it was almost a duty to generate inferior, worthily unworthy versions.

Fortunately, our weatherbeaten little Atlantic rock was buffetted from one side by the expansive likes of Sonic Youth, The Buttholes, Big Black (and from Ireland, My Bloody Valentine) and also from Europe, The Sugarcubes, Front 242, Einsturzende Neubauten and others, all of whom, in the different ways, dared to inflate, expand and rearrange notions of what rock could be, if it chose not to settle into the morose, trad-indie furrow.

The Young Gods were from Switzerland. They were formed in the mid-80s by Franz Treichler, a conservatoire-trained classical guitarist. However, while there was guitar noise aplenty in The Young Gods, they used no guitarist. Their initial line up was Treichler (vocals), Frank Bagnoud (drums) and Cesare Pizzi, who operated the sampler that supplied the remainder of their sound.

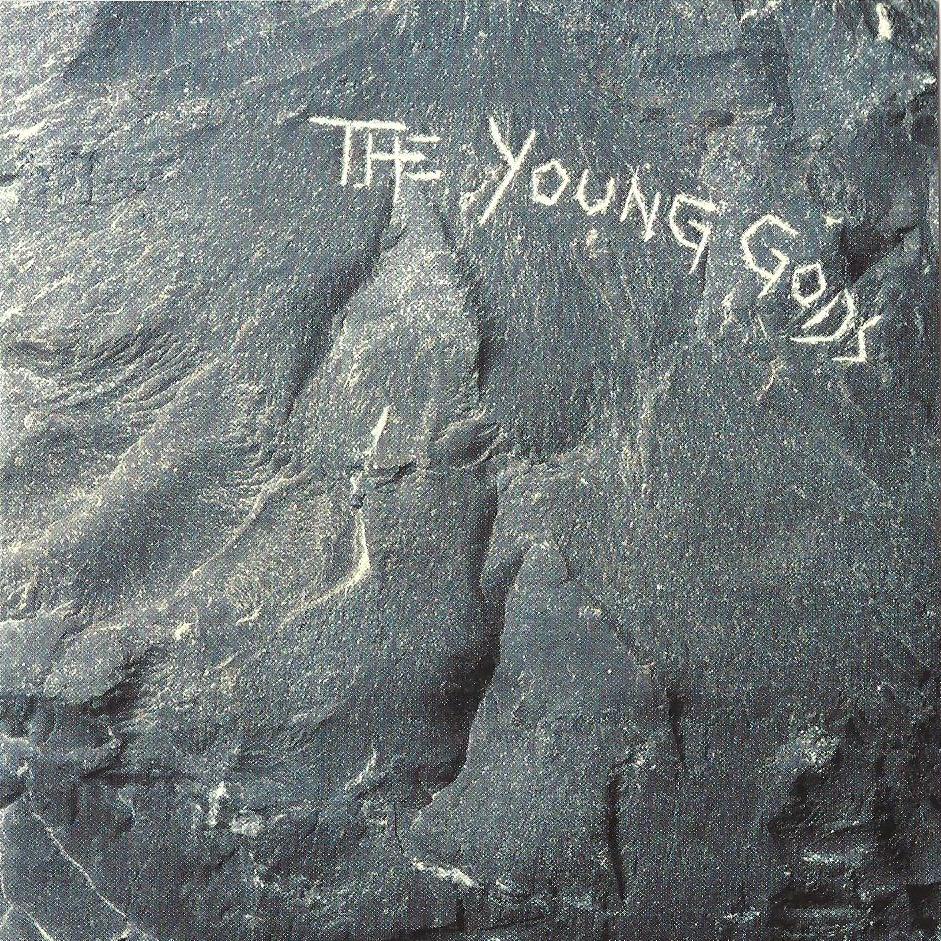

Released a quarter of a century ago, The Young Gods’s eponymous debut album featured a cover in which the band were depicted as stick-men chalked onto a stone surface, like early cave paintings. Their line-up and approach were unprecedented. It was as if history began again with this record, this group. We weren’t in Hull any more. Treichler bore some physical resemblances to Bono whose U2 had, with titles like The Unforgettable Fire, had pompously assumed the mantle of bearers of rock’s pure late 80s flame. However, as Rattle And Hum, their 1988 would confirm in all its nauseating osmosis-masquerading-as-homage, they were in deadly, earnest retrospective thrall to rock’s roots and origins, to Presley, BB King, to Bo Diddley, to antique soul and prepostmodern authenticity.

The Young Gods, by contrast, aspired to what might be called postpostmodernism. Though the turbulent, elemental sound spectacle they presented felt like Earth before the dinosaurs, The Young Gods’s use of samplers was symbolic – they used artifice and synthesis, mechanically retrieving the sounds of the dead rock (and classical) past, but forging them in such a way as to create something bold, grandiose and absolutely new under the sun. “They have chosen the right time to rediscover fire,” I wrote at the time. “They are at once a funeral pyre and a giant ignition.”

The Young Gods certainly got their first hearing among the more inquisitive of those into goth and post-industrial and certainly, in their unabashed grandiosity, with titles like opener ‘Nous De La Lune’ (We Of The Moon), featuring tolling bells and Treichler’s vomiting, bass growl, they were not short on portentousness. With its martial beat preceded by what sounds like the sounds of Martian heavy industry, it was, however, subtly unlike anything conceived by Throbbing Gristle’s world of moral decay or Neubauten’s deconstruction or Sisters Of Mercy’s moshpit-friendly shape throwing.

This is affirmed by “Jusqu’au Bout”, whose juddering progress and exhaust fume sputters of revving guitar feel both quintessentially rock and yet, in its strange and visible joins, revealing that this is mechanically simulated, revolutionary. Treichler’s melodramatic, pterodactyl-like screams again intimate that this a new prehistory is dawning here; an effect exacerbated on ‘A Ciel Ouvert’, in which the skies blacken and redden at time lapse photography speed. As with Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Voodoo Chile’, the lyric is about unrestricted, infinite capability. “Stop the wind / with your teeth / Encircle the earth / Pay homage to your being."

Then comes ‘Jimmy’, which could be perceived as in tribute to either Hendrix or Page, both of whose volcanic contributions to rock history are referenced here; the mid-section reminds of the abrupt, reverberating detonation that punctuates Zeppelin’s live version of ‘Dazed And Confused’. But again, the straight ahead rotor effect of the riff, feels manufactured, freshly minted, could only have occurred as late as 1987.

On ‘Percussione’, there’s a dialogue, a gladiatorial tussle between primitive, muscle-powered percussion and the synthetic variety, while on ‘Feu’, a looped riff crashes and burns over and over, as the track temporarily buckles under its own, lava-like intensity. The historical rules of progression, verse, chorus, are all suspended; America is no more, or has yet to happen. The Young Gods, insisted Treichler, represented “a quintessentially European idea of rock”.

‘Did You Miss Me’ is a temporary diversion, a Laibach-like version of Gary Glitter’s ‘Hello, Hello (It’s Good To Be Back)’, but ingeniously constructed from orchestral samples, and the “Yeah!!” chant a forgivably sly lapse into homage, drawn from a live album by fellow Zurich based innovators Yello.

The clouds lift hereafter, with early hit ‘Envoye’ driven by a fast-somersaulting guitar sample and hectic, motorik percussion. ‘Irrtum Boys’ is like some cubo-futurist take on Thin Lizzy’s ‘The Boys Are Back In Town’, stabbing at you from all angles. ‘C.S.C.L.D.F.’, meanwhile, loops a Ruts riff to solemnly mesmeric effect, the sampler used to frame, maximise and preserve its energy, which on the original suffers a conventional death by ordinary progression and decay. The song is broken up by what sounds like a moment of instant, nuclear annihilation, before resuming.

The Young Gods did not achieve instant success; their Swissness, their insistence on singing in French all precluded a wider audience, while some looked askance at the sort of extravagant language heaped on the group by writers such as myself and approached them suspicious of hyperbole rather than open to experience. In 1991, they did achieve the pinnacle of their commercial success and were namechecked by the likes of Nine Inch Nails, David Bowie and even U2. They continued to record, achieving notable brilliance with 1995’s Only Heaven, though today they are one comet among many in a dark sky of processed electronica/rock crossover.

I was afraid, coming back to the album and listening to it in full and in sequence that it would sound tinnily dated and disappointing in 2012, superseded by the sheer volume, capacity and weight of 21st century recordings – that it would seem significant only as a pivotal, if improperly acknowledged moment in the dialectical process. But no – crank it up and immediately I experienced again the rush of blood I felt as a young writer, having just interviewed the band in Zurich, heading to a cafe in the city that had been a Dadaist hangout back in 1916 in naïve search of psychogeographic inspiration, blackening a notebook with screeds of adjectival frenzy as the album raged on my headphones. It retains both its molten power and own, grandiose sense of purpose – the fire that came along to torch an entire era of white-socked hipsters, crewcut mumbling indie dullards, smirking ironists, lumpen, Luddite grebos and post-Live Aid white soul hegemonists and Bono’s stupid big white hat.