It is 1995. BrrrrBrrrr. BrrrrBrrrr. A phone rings in a hallway. I stop building and burning and pick up.

"Hey Neil, is it ok to speak? It’s Ian Crause here."

"Yeah, Ian, blimey, how the fuck are you?"

"Fine. Disco Inferno is over. I’m starting a new band called Floorshow and I need a front man. I think you’d be brilliant."

Later, in fact for years later, I see it as the biggest missed opportunity of my life, lash myself at my craven chicken shit-ness, wonder what might have been. In 96 things are simpler. I’m in tears.

Disco Inferno is over?

Inconsolable.

Still, 16 summers later, absolutely inconsolable.

That band weren’t just a possibility, a chance, a favourite. They were the only fucking soul band we had; the only fucking pop band we had. When they were on they were the only band that mattered, the only real show in a British pop world being taken over by craven pantomime and the only noise that sounded like it had walked the inner chambers of your heart and head taking notes. The only fucking band that mattered. The only band.

"No sorry Ian, I’m too shy. I just couldn’t do it man, I can’t sing, and… I just couldn’t do it."

"Fair enough man. See y’soon."

We don’t speak again for 16 years. Until last week in fact.

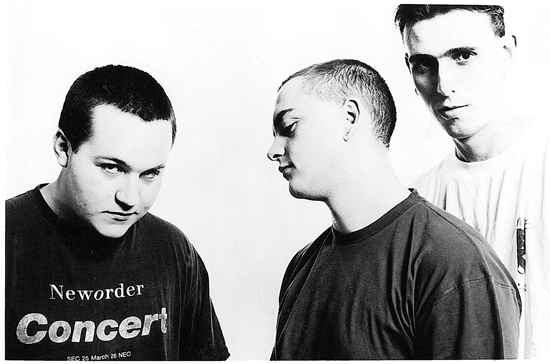

Disco Inferno’s unique, unmatched music is getting the reissue treatment it’s so long needed. 5 EPs collates the pentacle of 12"s Disco Inferno put out between 1992 and 1995. Hardly any of this music found its way onto DI’s equally astounding DI Go Pop and Technicolor albums. DI started releasing music in 91 with a few stunning singles for Che Records that were all faltering early steps, beautiful Durutti/Joy Div-inspired post punk as collected on the sublime In Debt compilation. In 1992 something changed that made DI go beyond being just a great band, that charged and transformed them into a way of life, a new way of hearing and seeing. Fired by innovations in sampling technology DI started making music absolutely incomparable to anyone else, a startling maelstrom of found sounds and broken rhythms, puckered by Crause’s liquid guitar and obscure, hugely suggestive lyrics. Music literally TOO accurate for its time. For three years, to my mind, they were simply the greatest, most important British band I’d ever heard.

And 16 summers on, we pick up where we left off, because for all of us, the hope can’t simply be batted away. It still burns, especially as pop’s doubtless gonna soon celebrate 20-years since Britpop with the same old red white and blue blinkers stitched into its sockets. And 16 years on, still absolutely inconsolable, I speak, separately, to the estranged-heart of DI, front man/guitarist Ian Crause and bassist Paul Wilmott but before we even get started I’m curious. Why the fuck did you ask me to do that Ian?

"You are imagining this. I suggest you seek some kind of help."

Shit, really? I wouldn’t put it past myself to have daydreamed it. But no, I remember, clear as day, I remember putting the phone down trembling…

"No. I’m joking. What a cunt I am. I did it because I wanted to be in a band with someone I liked, who made me laugh, who I could relate to as a mate and who had an aptitude with words as I had decided to just be a musician again and not sing. You should have done it. It might have made all the difference, seriously."

Fucking guilt trips, how many things a moment of doubt can derail.

Where were you in 92? Were you in love? Did you have someone on your arm? Did you have places to go? Clubs you loved? People you loved? I’m ever so pleased for you. I had none of that myself. Just plastic to live by. The kids, my peers, my contemporaries, generation-Britpop and me in 92 were never gonna truly get along because we wanted different things. They were cool, sexy and young in head, heart and body. They wanted music that sounded like life, that filtered it, that made it fit, funny and whole. Bluetones. Shed 7. Blur. Oasis. I, prick, gobshite, lonely, 19-yr old pensioner, could unfortunately only exist on music that was life, that refused to filter or ‘satirise’ its times, that was only in hock to its sources in what pioneering spirit it could attempt to emulate – not what it could steal.

In 1992 what I did have was a record made by Disco Inferno, a four-piece from Essex who suddenly that summer started traumatising their stunning post-punk psychedelic gloom-pop with the sampling technology that had so excited them. They took their lead in this respect from Public Enemy and The Young Gods to start creating an entirely new kind of British pop music. "The gulls are coming in off the coast/The smell of corpses passed them in." Crause didn’t sing with much volume, or humour.

"Mass graves uncovered, must be abroad – it can’t be here/ I can sense your violence, but I still don’t understand." I had Disco Inferno in my ear, on trains, on the street, in my room, everywhere. "How when the past seems dead and you’ve got the future/ In the palm of your hand". Disco Inferno came out with a single in the summer of 92 that I heard on no dancefloors, true glorious, fearless British pop. "Foreigners get hushed-up trials/ And you’re waiting for a knock at the door/ Which would tell if you spent the next few years/ Free from life attacked by petrol bombs/ The price of bread went up five pence today/ And an immigrant was kicked to death again."

These words were not projected from a pretty-boy drama-school boy, all fringe and jazz-hands, but mumbled, hunched, choked out, from the ungainly genius Ian Crause. Along with his friends Paul, Daniel Gish (keyboards) and Rob Whatley (drums), he spoke more clearly of the a-z of fear I was inhabiting than anything else in 92. This was music that entertained no delusions about us all belonging again, that knew how dangerous a sense of belonging could be. "And I’m scared for my life for the first time in it/ And we’ve known all along that a home can put your life at risk/ So I guess we’ll just disperse again." The real battle in 90s UK pop was never Blur Vs Oasis. That was just a quote-generating cooked-up PR confrontation between different versions of the same hiding, the same retreat. The real battle was between a shaky, scary, thrilling, possible future and a definite, drab, permanent past. The real battle was Disco Inferno vs. The World. Crause might be older, wiser, but he’s still bitter about his band’s defeat.

Ian C: It’s a very thin line between doing what Blur did and what we did, especially before the sampling. Similar influences to a degree though, 60s music, post-punk – but I think the fundamental difference between us and most of them was that we were excited by music, not music culture. There was a lot of received wisdom at that point about there being apparently nothing new under the Sun and as there was no such thing as a genuine artist, and because the audience were all so clever that they chose not to be musicians but to earn money in proper jobs.

The bands who came from this milieu seemed to be able to see that being in a band innately as a cultural and career activity, making it by using the crudest cultural building blocks. That, of course, lent itself more than anything to irony and distance, which they had in spades, [something] that we couldn’t do in music. We were too angry for that. I mean, if you don’t believe in anything, what is there to write about? That’s what Britpop was like. One or two of those Britpop types have surfaced recently in pseudo-artistic culture vulture roles and it’s interesting to see how some of them are spiritually as young and exciting now as they were back then. Read that how you want.

Paul W: We were doing something that was out of kilter to what was happening around us. I’m not sure we realised at the time how difficult it might be to get people interested in what we were doing. What we were trying was not that radical. Essentially housing new technology and means of expression within a ‘pop’ format. 15 years seems a long time for something so simple. Especially as Ian was always worried that other bands would be doing it and reaping the rewards ahead of us [in the band’s lifetime]. I think that if Ian’s voice had been more traditional, the music would have been palatable to a wider market. It’s only now, with the huge proliferation of music both past and present via the internet that people are more willing to accept the awkwardness of the overall sound and delivery. If the rumoured Coldplay cover of ‘A Night On The Tiles’ happens, then I fully expect the arena dates to follow next year.

Do you think DI were always gonna be out-of-the-loop of mainstream UK pop in the 90s just by dint of where you came from? The wrong bit of Essex.

Ian C: Essex is the heart of where the white working class who took Thatcher’s shilling and began the process of destroying English society settled. White flight the BNP calls it: the whites from inner London decided to get clear of the blacks and Asians and move out. They are really the white working class heartlands of the south east. You will hear the cockney accents that have disappeared from inner London there now. There’s definitely something in the demographics but Blur come from what I’d call High Essex, out in Colchester. There’s a lot of the posh middle classes out that way, even if they do put on cock-a-knee accents like Jamie Oliver to try to fit in.

So Britpop was middle-class?

Ian C: The ascendancy of the newly dominant middle class seeped through everything. So the Britpop thing coincided with this, certainly at the start of it. A lot of these bands were most definitely upper middle class and privately educated, from what I saw of them. Albarn is obviously a very clever bloke who like a lot of middle class people sees the working class as a bag of mythical others to be encountered and observed. You’ve got the performing monkey for them to laugh at, like they do with Shaun Ryder, where they can listen to him yet feel superior at the same time through the smirks; you’ve got the hard man archetype that they’re so scared of after closing time on the buses and streets of the big city, which was why the 90s were full of lad’s mags and fake football bullshit as they felt they had to hold their own on in a hostile environment.

I think the whole Cool Brittania thing in the light of Blair’s neo-liberal legacy is a beautifully bitter and apposite soundtrack. Pulp are the obvious exception due to their lyrics. I remember Geoff [Travis] played us an advanced cut of ‘Common People’ in his office shortly after he got the tape back to see if we were interested in working with the producer, Chris Thomas, but all you thought as you heard it, even that first time, was, "This is gonna be a classic song." It was that obvious. The Britpop thing in hindsight makes a decent soundtrack to the push over the top as neo-liberalism had a last good crack at destroying British society by creating massive class difference within it, whilst pushing pseudo-liberal propaganda to paper it over.

That’s in retrospect though Ian – at the time what did you think of your contemporaries and ‘peers’?

Ian C: Well our generation has to have been one of the most conservative in Britain since the Second World War. That’s why they felt the need to dress up in beads and go on about how stoned they were, pretending to ‘dig’ Hendrix and the Doors. I found it disgusting at the time, to be honest. I’m actually surprised that little chap from Kula Shaker never got an Ivor Novello. His drivel embodied our generation’s play acting at rebellion as much as anyone. When you hear his social views he could have sat in Franco’s cabinet so it kind of embodies the whole picture for me. He’s not any kind of an exception – he was the epitome.

Was the lack of political bite partly what annoyed you about Britpop?

Ian C: Well it annoyed me about my generation. In about 1990 a lot of the people who rioted and demo-ed would have been those opposing Thatcher through the 80s, I think – older people. Our generation was the one that told itself and anyone else who’d listen not that they had come up with any answers to anything but that all the answers had already been found or were not worth knowing. I used to read the letters in Melody Maker through this period all of them trying to educate the likes of you and me to the illusory concept of originality and how it could never be achieved.

Which really meant: "My name is Joshua. I am taking a degree in critical theory at Leicester Polytechnic. I would have liked to have been an artist of some sort but I tried and it was difficult so I have decided to let you know for your own benefit that it can’t be done and oh, here is the empirical proof in a book I heard about on my course. I’m off to Thailand now where I will pretend to help some brown people but really just laze around and take drugs and drink lots. When I come back from my round the world doss – sorry, cultural odyssey – I’ve got an internship lined up at BAE/Credit Suisse/Deutsche Bank so I’ll have won anyway and you’ll all still be poor.

And indeed they did, and indeed I was, and still am.

I remember David Stubbs telling me about bumping into you the week after he gave you single of the week (the Maker and Lime Lizard were pretty much the only boosters DI ever got) and you telling him you were skint and working in Tescos.

Ian C: Yeah, well, it was the generation where the class war against the poor really embedded itself in the culture and art of the time like second nature. That’s what Britpop was to me, a bohemian fantasy they were indulging in, which is one of the knock-on effects of living in a destabilised society, you can dress up like the poor and mimic them but when the whistle blows it’s rags off and home to mater, pater and finance capital. I hope that complacency and arrogance were very much of our generation and I’m glad we’ve had our time, to be honest, cos the kids coming through can now start clearing up the mess our lot left – and what a fucking mess it is, eh? Their immigrant underclass shadow gave them a taste of working class reality a few months back and they didn’t like it, did they? All their organic coffee shops got smashed up and the latte went everywhere.

Out they came with their fucking brooms and rosy cheeks, sweeping the ‘scum’ away. Did you see the photo of them holding their brooms up in The Guardian? They need to invent a red-cheek filter to go with the redeye one. As one of the illiterate ‘scum’ in their eyes I found that part of it funny, to be honest. Welcome to Paaaaahhhk Life! I look at that whole Britpop period as part of a necessary fantasy where the newly ascendant middle classes came in from the shires and camouflaged themselves in working class garb before they really took over and financially raped the whole place into buggery, which is where it now is.

Nice to see we’ve all moved on. From anger you found it difficult to live with, to analysis that leaves you resigned but still resistant. S’called growing up. Disco Inferno made the most grown-up kids music I’d ever heard.

"I may need dreams from time to time,

But dreams aren’t keeping me alive.

My dreams have torn my life in two–

Now I just need a rock to cling to"

What became clear on the Summers Last Sound EP and the astonishing other EPs that followed, as well as DI Go Pop (the 2nd greatest British LP of the 90s that forced both DI’s pop sense and sonic-speculation to dazzling new heights) was that what was revelatory about DI wasn’t that they were ahead of their time. They were (more fatally for their success) entirely of their time, honest about that time, in an era where everyone else was too scared to do anything except look back and pretend.

For me isolated from the mainstream by dint of race and radginess, DI spoke deeply because it sounded like they too were stranded without friends, following ideas in isolation, unfashionable yet on fire artistically and mentally from music that usually had nothing to do with the band-conventions Britpop would cling to. Futurism not as concept or theory or attitude but as the only way to stay alive, respond to the shittiness and wonder of the present.

Ian C: "It’s related to the definition of the word prophetic, I think. The word is often taken to mean being able to see into the future yet it really means to see to the heart of things, thus rendering time irrelevant. Ted Hughes’ translation of Agamemnon has the most electrifying description of this if you can get hold of a copy, all about how the eye that opens into the grave sees to the heart of all things. The application to any of the arts of this split interpretation is obvious: technical innovation was increasingly seen through the high arts in the 20th Century as being prophetic in itself, as it shows the truth by showing process. So while we’ve sometimes been read as having made a very cold, elitist kind of arthouse music, I think it’s a misreading. Our sound was bent to human words and emotions: song, for all its shortcomings.

From 92 I had become hell-bent on innovating cos things like Public Enemy and Young Gods blew my mind, but it’s when it’s allied to a human perspective that technical innovation holds its artistic power otherwise it’s just a technical exercise. That’s what a lot of that post rock is, as I understand it. So while I tried consciously to innovate, as I’d absorbed the influence of doing so partly from the likes of you and your old colleagues like David Stubbs, my instincts led me to value the other side of things and that’s the essence of the band’s appeal, I think. We had both sides. I like the fact there seems to be no consensus about what our best recordings are. Some people like DI Go Pop most, some the EPs and some Technicolor. All will say they have proof of why X is the best as opposed to the others. I like that and I have no favourite.

Paul W: We had recorded the Science EP [last EP for Che in 1991], got some slightly better press, but were still playing to the bar staff most nights in any venue that would let us play. We were frustrated, ambitious and wanted to make an impression. Bands that we liked were using samplers and there seemed to be no reason apart from the financial that we shouldn’t look to use them. We were listening to Blue Lines, Loveless, Adventures Beyond The Ultraworld; open to possibilities. We were conscious of the clone indie kid and wanted to be anything but tribal. We had been together just over three years and collectively were getting nowhere; it became a shit or bust moment. At least we would die trying. I always thought that the thing that made DI distinctive post-In Debt was the complete lack of pretence in our approach.

"We were more naive than a lot of our contemporaries. It took us a few years before we were aware of Can, Beefheart, Neu! There was no college/University education – we took what we knew straight from school via the MM and met people in a difficult, rudimentary way via the pay-to-play circuit. Rehearsing next to mainly pub bands. We were straight from the A12, close to London but definitely not apart of it – on the outside looking in. Rob and I drank in a pub next to the Gant’s Hill roundabout which was our main social haunt. Our vehicle of choice (actually Rob’s as he was the only one with a licence) was a beaten up Ford Capri. A lot of the people that we met had the confidence of education. I often felt much safer at a football match, than trying to have a conversation with somebody after a gig.

DI were always a pop band in my mind – is post rock is a term you’d reject?

Paul W. We certainly never called ourselves that. Well before such a term had been devised, Ian and I started off rehearsing in his bedroom in Redbridge, Essex, with bass and guitar, via a double jack adapter going into the mic socket on his hi-fi. Rob and I were very much from working class backgrounds, both living at home with a lot of encouragement from our fathers. Ian from a more middle class background with a greater need for rebellion, culminating in a regular freak out of bacon and avocado sandwiches in a kosher kitchen – it was wild.

Ian C: Most of these other what are now called post rock groups, I think they regarded us as a kind of tinker-toy group because of the pop songs and the sampling so there was little chance of them deciding to follow us in the sampling – no critical consensus had been built for them to aspire to it – we kind of got ours from Public Enemy, who were too black and the Young Gods, who sang in French, for fuck’s sake! And it wasn’t seen as ‘serious’ enough, perhaps meaning it wasn’t seen as commercially viable enough… who knows. Anyway, I did it cos I had the ideas. Remember ideas? Good, weren’t they? I wanted to be like Public Enemy and The Young Gods so I bought a Roland S-750 sampler with my savings and sat in my bedroom for 6 months (when I didn’t have to go to work) and started programming stuff.

I think a lot of them post-rockers (like the Britpoppers) had had musical training so they aspired to classical musical ideas as something beyond the pop song. By contrast most of our stuff was three or four minute pop. Also, most groups dressed up to take the stage whether they did leftfield art house stuff or went on TOTP pretending to be working class. Paul and I were naturally two of the scruffiest cunts you could find so that was never gonna happen, added to the fact that once we had the sampler thing going we became able to either silence, repel or provoke violence in an audience just by playing our songs so it didn’t seem necessary to dress up. If an audience can’t hear something they have never heard before, and which they had been told was impossible to do, and not feel the need for the artists in question to black up, twirl canes and prostrate themselves, then fuck them.

Also I think us being a bit fat made it look like we weren’t bright enough to do what we were doing and that it must have been some sort of accident. Some of the more middle class people around the band often mistook me for some kind of idiot savant despite comparatively few other people of any age or background being able to do what I had done to the most populous art form in the western world before I turned 18. I did not like that and I started to get more bugged by it as the years went by. Nascent class consciousness, you could call it.

Live DI were just astonishing, entirely unique in their use of technology and more-importantly their attempt in music to reflect their consciousness with utter accuracy. A 93 gig at Sheffield Leadmill is possibly my favourite gig of that entire decade. Most British pop at the time used old techniques to make people feel secure and on steady ground. In contrast DI sounded like a simultaneous rollercoaster, flood and earthquake – they were the sound of where your young head was at, a sound that refused to bow that head in deference to the past or any sense of cowed inferiority. DI didn’t have influences. They had chaos.

Ian C: I had a kind of pantheon of greats who were my touchstones: Joy Divison and New Order, Gang of Four, The Only Ones, Wire, REM, Public Enemy, My Bloody Valentine, the Young Gods, Velvet Underground, Talking Heads – so many, to be honest, too many when I started listening to classical music as well to even think about being ‘influenced’ by them. They were just part of the sound in our heads.

Heads also affected by everything else.

Ian C: All our family lives were a mess, to be honest. It’s not for me to talk about anyone else but I regarded my own family life as having been the most stable and middle class of the three of us, which in hindsight was pure naïveté because it’s only as you get into your 30s and you look back at your childhood and youth that you attain the perspective to be able to think, "Jesus Christ. I can’t believe I put up with that." I was bullied all the way through school for being a fatso and a weirdo – basically I was intelligent and ended up with a lot of thickos or inadequates and mediocrities (the most dangerous sort of people) – and when I look back at some of the interviews I was quite clearly disturbed by having gone through this and needed help.

In my late 20s I eventually began the process of psychoanalysing myself by thinking long and hard about how things got to where they were but this was long before then. So I was genuinely miserable, as I think a lot of people are. I had been told by pretty much everyone I was talentless and would fail, including my own family, so the amount of guilt I felt about being in the band was huge and as it became apparent we were failing it started to affect me. My advice to anyone being bullied is to knock their bully’s head off now. Otherwise you will be bullied all your life. I realised after a while I wrote in what I now recognise as quatrains and couplets – the most basic, doggerel verse – and held on to it like a guide rope in a storm, especially as the sound around the words took off into crazier places. Thematically I tried to place myself in my world and make sense of it. With no framework behind it. Just intuition.

All the joy in my life had rotted away,

I saw a vision in blue and my blues flew away.

And just for a second I truly believed,

Though I don’t know what in.

We tried to talk to each other,

But the words that came out of our mouths

Were carried away on the wind,

Which turned them inside out.

In desperation I tried

To communicate with my eyes

When all you’ve seen is people’s pain,

It’s hard to feign surprise.

And we just smile. The beauty Disco Inferno bought into the world carries a bitter, brackish aftertaste for me. It was the first moment as a pop writer where I fully apprehended my own powerlessness, and how the delusion that you can affect pop music in some way can never battle the wider cultural forces at work in the era you’re working in. I started reading the music press because one day I was walking through WH Smiths and spotted Public Enemy on the cover of Melody Maker. A decade later, and a couple of years into the time I ended up writing for Melody Maker black music had been pretty much banned from the cover, and the pioneering fearless spirit of 88 that would’ve had DI on the cover like a shot was being slowly replaced by a cowardly ABC-fixated terror-of-the-new that gave us three page features on Zoe Ball, page upon page of shit rag-mag bollocks and theme-park visits and stickers and sex-issues and desperation.

One of the first things I ever wrote was a Single Of The Week review of the astonishing ‘Second Language’ single. I wasn’t dumb enough to think DI’d be on TOTP the next week, but at the same time the sparse tiny-numbered disconnection of DI’s audience, the rarity of finding anyone else who understood just how great they were, became disheartening, for me, and I’m sure, for David Stubbs, Taylor Parkes, Lucy Cage, Jon Selzer, Simon Price and other fans who’d written about them. Sorry about the reviews lads. Reverse Midas.

Ian C: Unfortunately, you bastard, I was certainly lulled into a false sense of achievement. I remember our manager once telling us we had enough good reviews to wallpaper our houses with but we needed to pay our bills. It did start to become apparent in the last year or so that the reviews, especially in MM, counted for absolutely nothing in sales terms, which I belatedly came to realise were the be all and end all of being in a band if we needed to survive. I had just thought if we made amazing sounding music and lived record to record on our merits then we’d survive but there are no rules about who gets to do that, are there? Otherwise Glen Madeiros would still be playing Wembley. I was burnt out, to be honest, and the thing with Paul really finished it all for me. Reading became a sanctuary for me and a way to keep expanding and working into the future, so by about 2000 I had completely closed down as far as modern music went. I kind of felt that when someone caught up with what we’d done then wake me up, you know, and I’ll have a look? Otherwise leave me in peace. I just had my head in books for a few years. That’s another one of the best things I ever did and know I won’t regret on my deathbed.

Paul W: We slogged our guts out for six years trying to develop, evolve, create with very little reward. Ian was exhausted creatively and ran out of steam. We needed to take time to take stock and to spend the next 12 months working up new material. Ian couldn’t bear to be in the same room with me and convinced himself that I was the sole reason for most of his woes. He suggested that he write and record the next album his on own and Rob and I should write the album afterwards in readiness. An idea that I thought was bizarre and unworkable and created a way out for him. We had become totally disenchanted with the music press, which was extremely limited then.

The NME completely ignored us throughout. We had some great pieces in the MM, but were never actually able to nail a full feature and could never gain any momentum. Radio completely ignored us with the exception of a few loyal local radio DJs. We tried on several occasions to get on tours as a support, but weren’t able – until finally Steve Severin asked us to support the Banshees. What is more frustrating is that we were finally getting some recognition as we split. The last gig that we had played was our biggest, headlining at The Purcell Room which was also featured as a Mixing It session on Radio 3. I recently tried to get in touch with Ian through a third party recently to discuss the release. I was told that he has no interest in speaking to me. Rob seems to exist in the ether. I guess the reunion is some way off. I best keep that million-dollar Coachella offer to myself. Oh shit.

Stranger things have happened. Weirdly for such an elementally British band, DI have long been of almost mythical status in the US. My old Maker/Metal Hammer mucker Jon Selzer recalls wearing a rare orange DI shirt to Washington DC and being stopped every five minutes by someone insistent on telling him how much DI meant to them. In recent years bands like Deerhunter, Animal Collective and MGMT have acknowledged DI as a big influence, MGMT’s Ben Goldwasser rhapsodizing that they "still sound like the future". But what’s galling is how unrepeatable DI’s music still sounds, how the precise mix of people, environment and technology that created it will never come together again. As a fan I can only thank DI for ever existing, particularly at the time they did, because they offered a faint hope of a party I’d be proud to attend, an art I’d be proud to follow, a community, no matter how displaced and splayed out, that provided a genuinely and specifically English dissident pop alternative to the Cool Britannia bullshit patriot-games being played everywhere else. C’mon lads. Why not ride that reunion train to the land of gravy?

Ian C: I have no desire to do it again. Who can speak for the future but I think not everything has to be recycled to extract every single drop of life and mystery out of it. It’s done. I’m more interested in the music I’ve spent the last few years working towards which still taxes me every bit as much as all the Disco stuff ever did – and God knows it’s taken me long enough to get to the point it is finally starting to work – and it’s a great feeling to still feel I’m at the start of something big. Never having had a record come out that was taken seriously has the added benefit of making people’s reactions a near irrelevance.

What does it feel like now, listening to the 5 Eps?

Paul W: It’s strange listening to the music now, time has created a detachment. It’s difficult to be objective about it having been so close. I’ve got no idea if it’s good/bad/ok. There are certain tracks where the purity of the idea is realised more than others, with something like ‘Summer’s Last Sound’. I’m a little uncomfortable with the looseness of most of it, although I understand that if the recordings were perfectly quantized the product would create a different impression. I also think that there was a lot of unrealised potential. The pressure to keep moving at too swift a rate is something that although benefitted our evolution in the short term, caused Ian problems in particular. He put the band under enormous pressure and personally felt the strain in song writing. I think that if we had taken a longer view and allowed ourselves more freedom to create over a period of time, we could have achieved a better balance. Virtually everything that we wrote was released. The time between writing and recording was usually very short and didn’t leave much time to fully evolve each cycle. The writing and recording of DI Go Pop was the longest time that we had spent out of a studio concentrating on a spread of songs. I find it difficult when I hear about Ian’s issues throughout this period, as they are usually horribly remembered and pay little or no attention to his own behaviour which can at best be described as erratic. I do become embittered when I listen to the music as it brings back enormous feelings of resentment. We could have continued to exist had Ian not been entirely impossible. We never truly discussed the issues that he was perpetually angry about as he had communication issues. I didn’t fall out with Ian – he fell out with me and didn’t want to discuss it.

Ian C: I actually find it less painful to listen to now than when we were making it, to be honest. Back then I was close to it and young and as the lyrics had lots of personal stuff embedded in them, and I think were sometimes badly written. It is often pretty embarrassing to hear your own stuff in these circumstances. Now I’m almost 40 so when I do have a little listen to it it’s as though I’m listening through a strong set of memories. I think if I hadn’t been in the band and I had stumbled across us recently I’d be quite surprised by what I was hearing, given that it seems to have become commonplace to talk about how dull and conformist most rock music is. I would have been surprised by it at the very least, for sure. So I feel, to quote Peter Cook, nothing but pride. Empty, stupefying, vainglorious pride. My regrets are that I wasn’t able to make it as a musician and have had to spend most of my adult life working in low paid jobs being treated as, at best, a performing cockney monkey who can read and at worst a savage. Class is alive and well in the City of London, I can tell you. So, whatever I think of the recordings, having made them is one of the few worthwhile things I’ll be able to look back on. Obviously my family life and kids is another. Strangely enough I don’t recall any of the documents I’ve photocopied for lawyers in the last 15 years with anything like the same pride. I’m nothing but glad I did it.

Same here. 16 summers since. Inconsolable.

Five Eps is out now on One Little Indian

Next week: Part Three: I Hate Lovers – Insides and ‘Euphoria’