As soon as a jingly-jangly indie band appears today, the C86 tag isn’t far behind. And yet, this wasn’t always the case. Over time we seem to have diminished a scene that was far more musically and culturally complex that is often assumed. For all its janglyness, C86 was about much more than just that.

Looking back 25 years to the original C86 era, the Britain of then might be unrecognisable to us today. Unemployment into the millions, rising inflation, an unrepentant Tory Government; it’s difficult to comprehend, but that’s what life really was like.

Musically, Live Aid (which had taken place a year earlier) perfectly exemplified the landscape of the time with a rosta of bands so irredeemably anodyne they managed to make Queen look interesting.

Against this background, a musical rebellion was fermenting. At first it began in isolated pockets around the country, in places like Bristol and Glasgow but would soon coalesce to produce one of the most eclectic scenes in the short history of independent music.

One of the earliest people to really pick up on this change was Roy Carr, then a journalist with the NME.

"During the mid 80s, a few of us at the paper were starting to hear and see a load of bands coming through with a different sound to that which had dominated the independent scene for much of the earlier part of the decade. You got the feeling that something was happening, like the ground was shifting slightly."

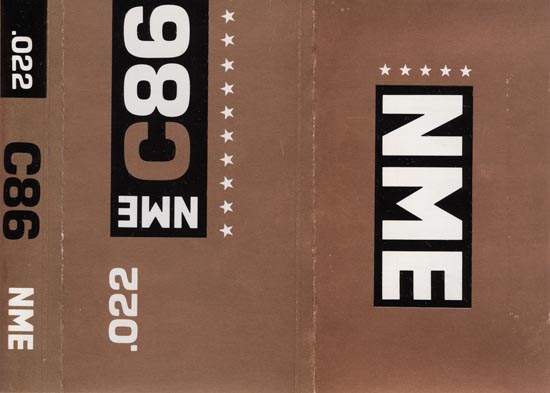

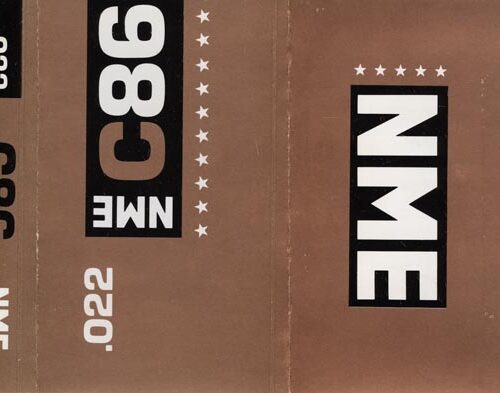

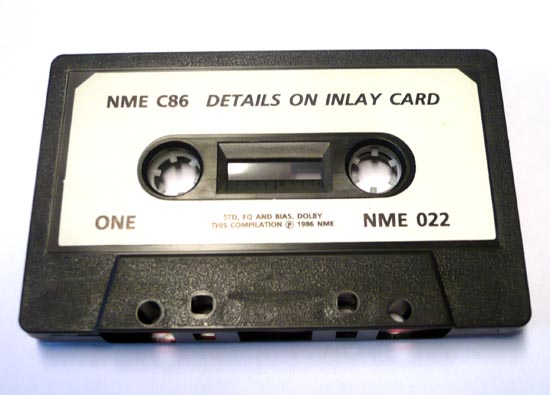

At the time, the NME was fond of putting together and releasing mix-tapes covering any number of different genres. It might sound quaint today in an age of unfettered access to anything ever recorded, but in those far off days a simple mix-tape could be one of the best chances for its readers to get hold of something new.

"We thought we’d do one of these for what was happening in indie music at the time. I’d done it for the paper before in 1981 – the imaginatively titled C81 – and that had been quite popular. So a few of us got together and started picking the bands we wanted to go on the tape."

The tape did well, selling thousands of copies via mail order and eventually being released as an LP a year later by Rough Trade. According to Sean Dickson, former lead singer with The Soup Dragons, this success acted as something of a catalyst – not just on the 22 bands featured, but on the scene as a whole.

"The tape was the key to the whole C86 thing taking off," he says. "Aside from its impact on our profile, which was big, its release threw a spotlight on everything. I think what you can say is that it made what was underground suddenly over-ground. It took all these little scenes from around the country and pushed them together into the limelight – scenes like mine in Glasgow, where bands like us and Primal Scream had been knocking around for a few years; going to the same gigs, enjoying the same taste in music and sharing a similar attitude in the way that we made music."

What’s striking about the bands both on the tape and those associated with the scene is the lack of a defining sound. If you listen to it today, the NME tape alone sounds like a load of bands with very little in common.

"We sounded nothing like a lot of the groups," says Kev Hopper, bassist at the time with Stump. "Our song, ‘Buffalo’, is totally different to something like ‘Breaking Lines’ by The Pastels. When people today think of C86 it’s the bands with the fey melodies and jangly guitars that come to mind. But there were many other groups that were loud and energetic, such as Big Flame and The Wedding Present, and then people like us and Bogshed who were quite experimental. Listen to the tape today and it’s clear that the scene was about much more than just indie-pop."

It is possible to pick your way through C86 and find several bands whose music did share bits in common. Many of those from Glasgow, such as The Pastels and Primal Scream, indulged in the more classically fey sound normally associated with C86, whereas on the Ron Johnson label, acts like The Shrubs, Big Flame and A Witness released songs that were fast and furious. But these connections were limited, and overall there is little to unite all the groups together, beyond a certain under-produced quality that characterised much of what was released during this period.

"The thing about music round then is that the people making it were drawing their influences from so many different places," says John Robb, whose book Death to Trad Rock catalogues many of the bands around at the time. "Yes, there were bands that were heavily into the Velvet Underground and producing jangly pop, but there were others who were taking ideas from punk, blues, jazz, funk, rock & roll, ska, dub and anything else they could get their hands on and then twisting it all into something new."

And yet to say that these groups had nothing at all to unite them would be wrong. One of the strongest shared characteristics evident in the scene was the rediscovery of punk’s DIY ethic.

"This was all about bands doing it for themselves," says John Robb. "This aspect of the scene isn’t always appreciated. There was no grovelling to major labels. Bands pressed their own records, put on their own gigs, designed their own record sleeves and published their own fanzines. It could often come across as quite amateurish but most of the time that was because those involved didn’t care about being slick. This wasn’t corporate rock; these bands didn’t have to sell millions. They were making music their own way. This was independent music in the truest sense of the word. Anti-establishment and everything that trad-rock wasn’t."

Yet despite its obvious musical and cultural complexity, over time C86 has been reduced to just one thing: journalistic short-hand for indie-pop. Its role in the creation of this genre is certainly an important one; the jingly-jangly sound we all know so well was formed during the mid-to-late 80s. C86 bands played a huge part in this, building on the foundations laid by Postcard Records at the beginning of the decade. Indie pop, in all its various forms since, owes a debt to bands such as The Pastels, The Shop Assistants and The Bodines.

But this shouldn’t be the only recognised legacy of C86. Some of its more abrasive groups have been quoted as influences by bands as diverse as the Manic Street Preachers, Lambchop and Franz Ferdinand. What’s more, its success stories included groups like The Wedding Present, who reflected the energetic side of the scene. And a few years after C86 had fizzled out, its cultural dimension was also a clear spiritual influence on Riot Grrrl – something acknowledged by bands who possessed the same DIY ethic, such as Bikini Kill and Bratmobile.

C86 as a scene and a tag is a more complex beast than we give it credit for. In the spirit of the DIY ethic this is my attempt to get off my arse and do something to right the wrong that has been done to C86 over the last thirty years. Spread the word dear reader; C86 was jangly, C86 was fey but C86 was also about much more than that too.

Track Listing

Side One

Primal Scream – ‘Velocity Girl’

The Mighty Lemon Drops – ‘Happy Head’

The Soup Dragons – ‘Pleasantly Surprised’

The Wolfhounds – ‘Feeling So Strange Again’

The Bodines – ‘Therese’

Mighty Mighty – ‘Law’

Stump – ‘Buffalo’

Bogshed – ‘Run to the Temple’

A Witness – ‘Sharpened Sticks’

The Pastels – ‘Breaking Lines’

Age of Chance – ‘From Now On, This Will Be Your God’

Side Two

The Shop Assistants – ‘It’s Up to You’

Close Lobsters – ‘Firestation Towers’

Miaow – ‘Sport Most Royal’

Half Man Half Biscuit – ‘I Hate Nerys Hughes (From The Heart)’

The Servants – ‘Transparent’

The Mackenzies – ‘Big Jim (There’s No Pubs In Heaven)’

Big Flame – ‘New Way (Quick Wash And Brush Up With Liberation Theology)’

Fuzzbox – ‘Console Me’

McCarthy – ‘Celestial City’

The Shrubs – ‘Bullfighter’s Bones’

The Wedding Present – ‘This Boy Can Wait’