In the mid-1980s, the proliferation of samplers provided, for many musicians, a mere means to filch the choice elements of a supposedly superior past, from old soul licks to John Bonham’s gargantuan kick drum. The sampler became an instrument of postmodernism, a wry admission that there was supposedly nothing new under the sun and all that was left for modern music was to pick at the carcass of its history.

Franz Treichler, who had fronted a punk group in his native town of Fribourg, Switzerland, saw past this. He envisaged the sampler as a radical new means of reanimating rock music – breaking into the realm of the post-postmodern. In his bedroom, he began to create a new music, a new mode of composition which dispensed with the predictable structures and progressions of the conventional guitar trio.

Initially, he and fellow electronic musician Cesare Pizzi operated with just vocals, sampler and drum machine. However, they realised that this was a little too mechanical and so brought in drummer Frank Bagnoud to lend their sound a vital physicality, a greater sense of the man-machine dynamic.

For their 1987 debut, self-titled album, they worked with Roli Mosimann, also Swiss, who had worked in New York with the likes of Swans and Foetus. An instant critical smash, it reworked elements of heavy rock, metal, found sounds as well as classical elements to create a powerful collage, a cybernetic improvement of traditional rock that somehow hauled it back to its first principles – fiery vocals, thunderous percussion, concussive, looped riffs. It was a sound that would influence groups as diverse as Nine Inch Nails and U2.

They further developed their sound on subsequent albums, including their follow up, the more molten L’Eau Rouge, whose samples ranged from Hendrix to Shostakovich. However, on 1992’s T.V. Sky, with Al Comet, aka Alain Monod now working the sampler, Treichler decided to sing entirely in English, in the hope of reaching a wider audience – with it, the group achieved the pinnacle of their commercial success. In the 1990s, The Young Gods went on to be increasingly influenced by the sounds of ambient and techno, of which they created their own, uniquely processed versions as evidenced on 1995’s Only Heaven and its offshoot Heaven Deconstruction.

While they have not been the most prolific of bands in their 40 year lifespan, as reflected in the title of their most recent album Appear/Disappear, they have been among the most consistent and have continued to evolve. They have tended to oscillate between the “classic” Young Gods sound they established at the outset, on albums such as Super Ready/Fragmenté and more experimental outings, challenging both themselves and their audience, including 1991’s The Young Gods Play Kurt Weill, a reworking of German radical cabaret, Music For Artificial Clouds, in which they infused ambient with an underlying eco-consciousness and The Young Gods Play Terry Riley In C, their own take on the great minimalist composer’s open-ended masterpiece. Decades on, their curiosity and ferocious creativity remain undimmed.

‘Envoyé’ (1986)

Franz Treichler: I used to be in a band playing guitar and singing, but then I saw the sampling machine the Emulator in a shop for the first time. It was £10,000; unaffordable. But I thought, that it could be the future. I had to wait until a guitar pedal called the Super Replay came on the market before I could sample from vinyl using a turntable. I focussed on pure sound, not chord progressions. With ‘Envoyé’ I tried to do something with my own guitar though, rather than sampling anything else. I came up with something I would never have been able to play again… the magic of sampling! I had to get it right down on cassette. It was a whole new approach to writing. When we played live a lot of people would say, “Where is the guitar player hidden? Behind a curtain?” We were considered blasphemateurs, cheaters. The rock police would say, ‘You can’t do this! You have to have a guitar!’

‘Jimmy’ (from The Young Gods, 1987)

FT: Roli Mosimann, coming from working with Swans to be our producer, understood straight away what we were trying to do: to make music that wanted to kick asses. Plus, he was Swiss like us, so he wanted to help us. I had no experience of recording studios. He was the architect. He wasn’t involved in the writing. But I learned from him how to emphasise this relationship sounds can have when you juxtapose them, like colours on a painting, or by emphasising the space between sounds, or how to use and abuse studio effects. Once Roli told me to go for a walk and to come back in 40 minutes. He worked with the sound engineer on the kick drum. I came back 35 minutes and couldn’t hear any difference. I was like, what the fuck have you been doing? My ear wasn’t yet trained for studio subtleties.

‘Longue Route’ (from L’Eau Rouge, 1989)

FT: There was a visual shift in our album covers from the grey of the debut, to the molten fire of L’Eau Rouge. I was very interested in the elemental at this time – wood, metal, fire. We didn’t want our faces on the cover, we didn’t want people to be influenced by the look of the people making the music. Grey was the start of the band, earthy, stone – L’eau Rouge was like a burning plate of metal, fusion, fire; we were young, we had this fire. And it was a more romantic album, more classical samples. We did a remix of ‘Longue Route’ – it’s sampled from a record by Voivod, from Canada, who I really liked. It’s the story of the band – four years from our beginning felt like a long time! Touring, touring, on this trajectory, how fast things were moving, feeling like comets, not knowing where we were going, making holes in the sky.

‘Alabama Song’ (from The Young Gods Play Kurt Weill, 1991)

FT: This music was initially supposed to be just for special live shows. But we liked it so much that we included it in the repertoire for the L’Eau Rouge tour. So we thought we should record them. They were ready to go. Most people only knew ‘Alabama Song’ by Brecht and Weill because of The Doors, David Bowie covers. It made no sense to imitate the way Weill did it; we wanted to open it up to people who wouldn’t be sensitive to the cabaret versions. But Brecht and Weill were the ancestors of good pop muslc. The songs featured hookers, priests, criminals. ‘Mack The Knife’ is a deep, underlying, political statement. So all the things I love in pop – the popular style but also the underlying politics, the dissonance; what the Nazis called “degenerate” – it was the definition of what we called pop music from the 1960s on.

‘Gasoline Man’ (from T.V. Sky, 1992)

FT: I had spent a lot of time working in New York with Roli and that made me went to sing in English. After two months I started to think in English, to get all my inspiration from English words, from TV, from conversations with people. Singing in French is a bit exotic for some people, especially in the USA, Germany, and Holland. I wanted to get people to understand what we were trying to do. When we were in the studio I didn’t have a beat for this track, so Roli told me to go off for a walk. When I came back he’d assembled it, inspired by ZZ Top, who we both loved. As a drummer he could conceive of ZZ Top meeting Kraftwerk: rock, plus the precision of the programming. The lyrics came from a conversation with Al (Comet) who compared love with gasoline: how much love you can spare for family and for music, asking where people put their energy.”

‘Moon Revolutions’ (from Only Heaven, 1995)

FT: This was when we wanted to share our love for ambient electronic music with our audience: our love for Aphex Twin and Plastikman. It wasn’t easy. It was hard to persuade Roli to listen to Aphex Twin. “What’s this bubble music?” he’d say. I was sampling stuff like that, making big ambient drones. For ‘Moon Revolutions’, we wanted to go further into those dreamy atmospheres, psychedelics. wanted a long, beatless part that reminded me of early Pink Floyd, the track ‘Echoes’. I listened to ‘Echoes’ so many times when I was a teenager, before I discovered punk, which meant I had to stop listening to Pink Floyd. Now it’s more, the Pistols? Pink Floyd? Whatever. Throw it all in together.

‘Eregreen’ (from Music For Artificial Clouds, 2004)

FT: We had a commission from the Federal Office of Public Health, Switzerland. We were supposed to do a 30 minute ambient mix which people could listen to on headphones to while lying on long chairs next to this huge lakeside installation. So we generated a lot of material and some of it was a little more weird, not suitable for relaxation. We thought we might as well make a proper record which included the weird stuff. Also, I had travelled to the Amazon and made field recordings of insects and so on, which I included in the background. I like ‘Eregreen’ very much. It puts me in a state of belonging to the planet. Of course, not all our fans liked it, and our label said, ‘C’mon! Our contract says you have to provide ten songs with lyrics in a rock style!’ So they were nice about it and left us free to release this record, just not with them.

‘You Gave Me A Name’ (from Data Mirage Tangram, 2019)

FT: We were playing a jazz festival in Cully, Switzerland, playing three sets a night in this underground wine cellar, to 80 people maximum, for five days. In the middle of this wine making region you have this jazz festival with three main stages and twelve cellars with musicians playing everything from Dixieland to bebop to experimental, and one that featured music like ours, which is not really jazz but is in the improvising spirit of jazz. It was very fruitful. I took my guitar, we generated so much material, including this piece, playing in a Can-like style of jamming. Cesare [Pizzi] was back in the group and he was very much into jamming with his computer.

The Young Gods Play Terry Riley In C (2022)

FT: We first performed this piece in 2019 with an 85-piece orchestra that had some of the feel of a marching band about it. To prepare, I watched all these different versions of the piece on the Internet. It was supposed to be a one-time thing but we enjoyed doing it so much it ended up taking on a life of its own. We worked with dance companies, percussive ensembles, scored it for a film. At the end of the whole process we thought, let’s record a power trio version of this. And that’s what we did in 2022. It’s such an “out of time” piece – it was written in 1964 by Terry Riley but still sounds totally contemporary – with loops that are not quite the same length, each performer having to listen carefully to the others. It’s a mind blowing way of playing music. It is how it should be; forcing you to make decisions that give unexpected results.

‘Appear Disappear’ (from Appear Disappear, 2025)

FT: It’s a good description of us. ‘Longue Route’ was a metaphor for where the band was at time. ‘Appear Disappear’ is about our presence and absence from the music industry over the last 40 years. We have had these periods where we are off the radar but then we reappear. Also, it’s about how you position yourself in society, day by day, how we confront, or avoid what’s happening in the world, socially and politically. I read a lot of newspapers, I watch the news, I talk to people, but then at other times I think, I should stick to music, and express myself that way. Also, it’s about lifespan. We have 70 or 80 years on the planet; we appear, we disappear, this ephemeral thing is amazing. Having a body, all these things around us. I like this song for that reason. Lines like “matter doesn’t matter” is typically Treichler!

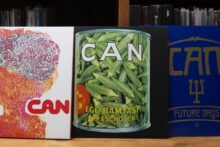

Appear Disappear is released on Friday via Two Gentlemen. The Young Gods tour Europe and the UK in Autumn