Cabaret Voltaire’s world has always been strange though it was perhaps at its strangest between 1974 and 1982, before tracks like ‘Sensoria’ and ‘Just Fascination’ propelled them more forcefully onto dancefloors. A major part of that story is Chris Watson, one of three founders, who reluctantly left the band in 1982 in order to pursue the vocation of television sound recordist. This was a métier that would take him to Tyne Tees in Manchester and then across the seven seas of Planet Earth, recording the sounds made by penguins and polar bears for award-winning David Attenborough nature documentaries.

At the invitation of Stephen ‘Mal’ Mallinder, Watson is back in the fold for a series of shows the Cabs are undertaking to celebrate fifty years of groundbreaking electronic music. Unfortunately, he’s absent today due to problems with his teeth, though Mallinder, on the line from his home in Brighton, is in irrepressible form with an acute memory of the ten tracks in question, even down to the variety of drum machines that were used.

Another absentee, of course, is Richard H. Kirk, who sadly died in September 2021. The musician had not long revived the Cabaret Voltaire name for solo work, and released Shadow Of Fear in 2020, the first album under the moniker since 1994’s The Conversation. Kirk’s death has robbed this reunion of a total consolidation, though Mallinder has ensured that the musician’s original parts suffuse the material at the shows they are performing, with the assistance of Ben “Benge” Edwards and Eric Random. Questions still remain as to whether this reunion could have taken place were Kirk still alive.

“I don’t know,” admits Mallinder. “Because Richard had gone down his own path. I always wanted to think a full reunion could happen, but I can’t second guess how Richard would have reacted to the idea. He’d become quite reclusive and he had developed his own specific way of doing things. He’d done an album, he’d done some shows – not many. It’s why I didn’t want to do new music, because I feel as though Cabaret Voltaire was always the collaboration of all of us. And even though he’s not playing on these shows, we’ve managed to sort of redo the parts he did. Richard’s completely embedded in what we do, and it’s done very much to acknowledge the work he did.”

Sixteen tracks will be getting the full visceral live Cabs treatment for one last year-long run of sporadic dates, finishing up at the Sheffield Octagon in October 2026. Nevertheless, Mallinder declares a caveat to the ‘no new music’ rule: “There is one new piece,” he reveals. “Since we started again, Chris has been working a lot more closely with myself and with Benge and Eric – he’s woven himself into the entire set and it’s brilliant. But being mindful of not wanting Chris to be a token presence, we took some of his sound design and integrated it into what we do to contemporise it. And out of that came a new track that Chris had been working on called ‘Tinsley’. It’s a very Sheffield-based track.”

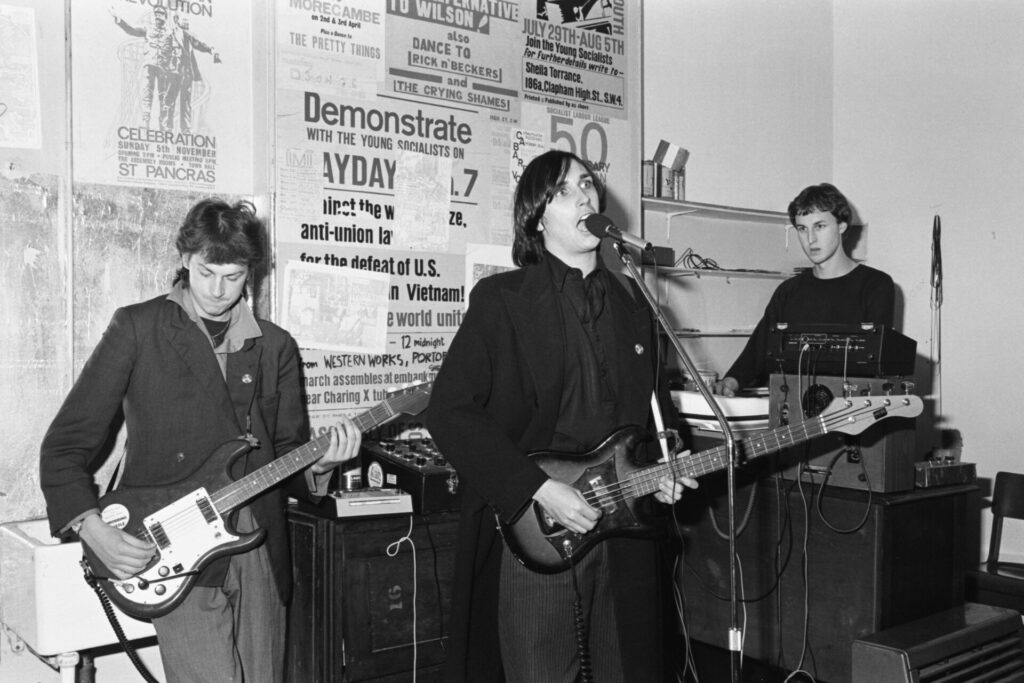

And back to Sheffield we go – to the attic in Chris Watson’s house in Totley where the three began experimenting with a National Reel-to-Reel tape recorder and assorted instruments, from 1973 onwards. What was it that drew them to the Cabaret Voltaire name, and were there any placeholders? “No, it was straight in,” says Mal. “The whole Dada thing was always a touchstone for us. We’d been through punk before punk happened, because we were connected with Dada and its non-conformity, flying in the face of authority and the bourgeois – it was kind of art and anti-art.”

Were they aware of Guy Debord and the Situationist movement at that time? “Yeah, we knew all about the riots of 68 but Situationism wasn’t as absorbed into mainstream culture as it is now. Obviously, now, it’s a heavyweight part of twentieth century culture, but the Dada thing represented something that was a little bit more real. The artists that came out of Dada – Tristan Tzara and Hugo Ball – they’re identifiable figures, and then you have Marcel Duchamp and Surrealism coming later. It felt part of a lineage that followed on and linked up with [musique concrète originator] Pierre Schaeffer, whereas the Situationists were more part of a movement. No tangible artwork came from it so it was also lacking a lot of artifacts and a lot of key figures as well, whereas Dada had representation. The Situationists had a spirit, it was really important, but it didn’t have those tangible connections that Dada and twentieth century art did for us then.”

‘The Dada Man’ (1974)

Stephen Mallinder: This would have been an early one from about 1974. Its nomenclature is probably quite notable, in the sense that we used to make tracks and we’d give them names which were usually quite tongue-in-cheek, as you can probably tell. We never sat down and said: ‘It’s going to be ‘The Dada Man’. We’d just go and work in Chris’s loft twice a week and make tracks. It probably sat there on a reel-to-reel for ages, and it became named ‘The Dada Man’, subsequently. It wasn’t that much more distinct from some of those experiments that we were doing at that time. We weren’t overly self-conscious about what we did – it was completely experimental, just working with a four-track TEAC, with delays and the primitive synths that we had.

‘The Dada Man’ would have been made before we were called Cabaret Voltaire. [It was eventually released in 1980 on the cassette-only compilation Cabaret Voltaire 1974-76 via Throbbing Gristle’s Industrial label.] I don’t know what made it distinct from any of the others, it was just part of that whole period of experimentation. In terms of the making of it, we just used to chop and change instruments. Richard played clarinet, and I did bits of voice. Chris and Richard were doing voices at the time too, so we would just bounce off each other. We were just kids in a loft, finding out what we could do with primitive electronic equipment and tape recorders. I think there was a smashed piano on the track. We did the John Cage thing and sort of bashed a piano around. We recorded it on cassette as it was being taken apart.

’Do the Mussolini (Head Kick)’ (1978)

SM: We recorded tracks such as ‘The Dada Man’, ‘Do The Snake’, and ‘A Sunday Night In Biot’, but we reached a point where we went, “Well, these are fun for us to listen to, but maybe we should try to distill this feeling into tracks that are slightly more coherent, so we can send them out to other people.” We’d had rejections and while we didn’t expect to get signed, we were still sending music out to record labels. There was a realisation by about 1977 that if we were going to send tracks out to people, it’d probably make sense to make them a bit more coherent, like ‘Do the Mussolini’.

Because it was the beginning of punk, we could see that there was a music press that was probably more sympathetic to things that we were doing. As a result, ‘Do The Mussolini’ got onto one of Jon Savage’s playlists in Sounds, and it was part of that first EP [Extended Play, released by Rough Trade in 1978]. I suppose it typified part of what we were, which was serious – as opposed to po-faced – but also quite tongue-in-cheek. And with this track we were being quite flippant.

‘Do The Mussolini’ was a nice finger flip to people, and we liked the idea of inventing a dance. I think it was partly inspired by ‘Do The Strand’ on the second Roxy Music album, For Your Pleasure, and we thought that was quite funny. In our own mad world, we created a dance called, ‘Do The Mussolini (Head Kick)’ which was obviously anti-fascist. We were making a statement but it was also intended to take the piss. What was one of the lines? “Black shirts and perverts”. So we clearly weren’t singing the praises of 1930s Italian fascism. As horrific as he was, Mussolini was also a figure of ridicule with all his movements and facial expressions. He was a ridiculous character in lots of ways.

‘Nag Nag Nag’ (1979)

SM: I don’t think we’d recorded in a commercial studio before ‘Nag Nag Nag’. We’d done Extended Play and we’d done Mix Up and Geoff Travis at Rough Trade said, “We need to make sure this single is the best it can possibly be.” And Red Krayola’s Mayo Thompson had kind of become connected with Rough Trade and I think Geoff wanted to really spearhead the idea of him being the in-house producer for the label. It was funny because he came from this subversive psychedelic scene but he always showed up in a suit.

The rhythm, with the tom rolls, was created on a Selmer drum machine. Obviously, now we’re doing ‘Nag Nag Nag’ live again, and the weird thing is, we couldn’t find any trace whatsoever of the drum machine that we used on originally. But the Korg Mini Pops has a similar setting so we actually had to adapt that drum machine so we could recreate the sound for these live shows. I remember when we went to buy that Selmer drum machine, back in the 70s when there were music shops everywhere. We were three fucking idiots who didn’t know what they were doing who went into a music shop at the bottom of a shopping mall and were really interested in listening to this drum machine. Drum machines in those days were pretty much designed for people who had home organs and used them to entertain their kids and neighbours; or you’d have a cocktail in a nightclub and somebody would play the organ live with drum machine accompaniment. So we already had a much older drum machine, and for some reason we thought we would be able to swap it for a newer generation one. We asked the guy in the shop: “Could we part exchange it?” And the guy behind the counter said, “What, for a fucking kazoo?” [Laughs] We said, “Alright, mate, don’t worry about it.” We walked out of the shop. We’d got some money from Extended Play, so we just went straight to the bank and drew the money out in cash, walked back in, slapped it down and walked out with the new drum machine. We didn’t say a fucking word.

Are you surprised at the cultural reach of this song?

SM: Yeah, I am actually! [Laughs] Jarvis Cocker always says it’s the best track ever. I shouldn’t give the game away but early on we did a cover version of The Seeds’ ‘No Escape’. Back then there was this kind of unwritten law that if you did a cover version, it made more sense to put it on an album where you would have to split the royalties with that writer so they only got a proportion of them. If it came out as a single, they got all the publishing. So we did our own version of ‘No Escape’ – ‘Nag Nag Nag’ has got the same simple kind of change in the chords. That’s all it is. I think what gets me, about how popular this track is, is we’re sort of known as these groundbreaking pioneers of electronic music and it’s the least electronic track we ever did. But it works, I’m not knocking it – it’s kind of fun to play live.

’Silent Command’ (1979)

SM: Richard and I particularly had grown up on ska and bluebeat. We really liked early reggae; The Skatalites and Prince Buster and all that. Then we really were into King Tubby and all the use of echo and later, obviously, Lee Perry. So it was part of our makeup, listening to a lot of dub. With the track, we had a rhythm and it just worked as an offbeat kind of ska rhythm. It works naturally for us because we were so familiar and immersed in that sound. We were really into delays. We used tape delay itself and we also had the Watkins Copicat for delays and, later – particularly in our studio space Western Works – we had echoes. We loved delays because we loved the idea of repetition and rhythm. And also bass, and getting into the idea of the space in music which is really important.

‘Seconds Too Late’ (1980)

I’ve got to be careful here. I shouldn’t really say this but hopefully Geoff Travis won’t read it. Geoff wanted to produce ‘Seconds Too Late’ but we were quite happy with the basics of the track: we already knew what we were doing. He got a co-production credit on it and I’m sure he had some input. But it did actually work out for us him being there because we wanted to use an EMS Vocoder, so we hired one and said to Geoff: ‘You can produce it… if you can bring the vocoder up on the train with you?’ Which he did, so we got the vocoder out of it. We did it in Western Works on the eight-track and it was all hands on the mixer because you’d mix all the channels live in those days. And we said to Geoff: ‘That’s your fader there, you keep an eye on that one, you ride that up and down’. We didn’t want to be rude, we kind of already knew what we wanted to do, and I don’t think that there was anything on Geoff’s fader [laughs]. The drum machine on this was the Electro Harmonix. It has very few variables on it and it’s really fat and basic. We also used it on ‘Sluggin’ Fer Jesus’ and ‘Taxi Music’ from Johnny Yesno which we’re doing in the live set as well. Luckily, Benge had one. He is an obsessive collector of drum machines that don’t really work half the time; which means he’s perfect for Cabaret Voltaire in 2025 because most of our shit didn’t work back in the day either.

‘Kneel To The Boss’ (1980)

SM: I mean, lyrically, vocally, thematically, this is about control and power, but the lyrics become a separate component. They’re in their own world, almost, and they just work. They kind of seemed empathetic to the track. I’m trying to remember the drum machine on that one. I think that’s the Selmer again. This one has kind of stood the test of time. I did a cover version – if you can cover your own song – in Sheffield once with members of In The Nursery, Floy Joy and Clock DVA. I think Chris played the organ on this one. It’s just got that really nice, simple tonal feel to it. We did it as a one-off 7” single, which we’d do if there was a track that was a bit catchy. Don’t put it on an album, save it and do it as a single, and then we could hopefully give it to somebody like John Peel who would play it on the radio. We liked the idea of working tracks around a format: certain records should be on 7”, others should be part of a collection as an album track, and certain tracks should be a 12”. Certain tracks could run at 33rpm because they’re more experimental. We loved playing with those.

‘Jazz The Glass’ (1981)

This has the swagger of Hex Enduction Hour-era Fall…

SM: It would have come out around the same time as Hex, so yeah, it does. We knew The Fall, we were good friends with Mark E. Smith, particularly around that time when we were both on Rough Trade. Mark used to say we were the disruptive northerners on the label, because at the time they had The Raincoats and Scritti Politti, so it was a little bit west London and we were northern.

We did ‘Jazz The Glass’ around the time that we did 2X45 with that amazing sleeve that Neville Brody did with the mad envelope that opened up. It was beautiful. As well as formats, we loved the idea of packaging too, so we went: “Let’s do a 12” and a 7” and bring them out together.” And they came out in a plastic Ziploc sleeve. You couldn’t buy them separately, you bought the 7” and the 12”. We liked to bring things out quite quickly. We were quite spontaneous. So if we recorded something like ‘Jazz The Glass’, we didn’t polish it into nothingness, we just went, ‘That’s fresh, let’s bring it out’. And Rough Trade were really good in those days, when we’d say that we wanted to bring this out as 7” and a 12” they were into the idea. The title ‘Jazz the Glass’ comes from Californian sixties surfing culture.

’Sluggin’ fer Jesus’

SM: I must point out that this came out before David Byrne and Eno did ‘Jezebel Spirit’ and all that. Tony Wilson always used to say, ‘They fucking ripped you off’ [laughs] but we were just doing similar stuff at the same time. It was similar, obviously, because it was kind of at the peak of American TV evangelism. The first time we were in the States was around 1980 and we were staying with V. Vale from Re/Search Publications for a while, and we became quite obsessed with all the TV we saw when we were there. We were kids from Sheffield in North Beach in San Francisco staying with somebody who had cable TV with a million channels, and loads of TV evangelists. We would record them because they were just brilliant showmen, these grifters, these hustlers. But the language they used to get money was so smart, they were just like market traders but selling Jesus for money over the telly. So it was the three of us: me, Richard and Chris in North Beach, recording the voices from TV. Then we came back home and put drums to it and played along with it, and that was it. My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts was just one of those things. That was on a bigger label and we were just on Crepuscule, the Belgian label which is part of the Factory Benelux imprint. Now it’s funny. At the time I bought My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts straight away and loved it. But it’s kind of funny when other people went, ‘Oh yeah, you got ripped off there’. But that idea was in the air at the time.

Landslide (1981)

SM: This is only about two minutes long! The live version we’re doing for these shows is a little bit longer – It’s probably about four minutes long [laughs]. It was quite nice when we did things that we didn’t do too often; it’s an instrumental, which is sort of weird. It’s just a real nice kind of breath of air track, isn’t it? We were capable of making tracks of all descriptions. Our reputation was for making challenging, confrontational music and trying to push the envelope, but at the same time ‘Kneel To The Boss’ and ‘Landslide’ and certain things had a different feel, not that there was anything wrong with the music. Not everything should be the same. We’re quite aware of that, so we quite liked it, and it just added a lovely kind of groove to it, really.

Was it throwing things into sharp relief like, say, Shakespeare when he drops some comedy into a tragedy? Not that this is comedy, of course…

But we do drop comedy into things. I don’t think there’s anybody who works collectively with musicians who doesn’t have a sense of humour, and everyone has their little in-jokes. So there is humour in some of the stuff we do and music can also offer light relief as well. I mean, we did a Christmas track called ‘Invocation’ and to this day, I think it’s absolutely beautiful, it’s a lovely piece of music. And we didn’t go, ‘Oh, it’s too nice’, we just went, ‘Oh, that’s different’.

‘Yashar’ (1982)

SM: There were two parts to this. There was The Outer Limits “70 billion people” sample which we had floating around and then the other part was the rototom rhythm which Alan Fish played. No one uses rototoms anymore but they were kind of small, very tight, high-pitched tom tom drums. And it had a real eastern feel to it, a bit like ‘Eastern Mantra’, that we were drawn to; the esoteric sounds and tonal kinds of things that come with eastern music. We were really into The Master Musicians of Joujouka and Moroccan rhythms. And it came at a time when we were listening to a lot of Miles Davis and Ornette Coleman and that kind of stuff, and Jon Hassell as well. So I think it was done at a time when there was a slightly more esoteric jazzy thing going on in a fluid sort of John Coltrane way. We never really had a style that we wanted to hone and polish and perfect, we were just like, ‘Let’s try something in a different vein’. We felt that all our tracks should stand up as individual, unique tracks, not just be a stylistic continuation of the track we’d done before. It quickly became a standard track for us to play live, because it was quite immediate. It’s quite punchy.

The Outer Limits represented the kind of otherness and weirdness that we were into. It also represented American popular culture, and we were kids growing up under the guise of the Cold War and the space age and aliens and all this stuff. But also, I think with the stuff we were doing in the 70s, there was a weird nostalgia for sixties sci-fi, and it’s a bit like the Mark Fisher thing whereby our ideas of the future were really still quite set in that idea of Forbidden Planet and The Outer Limits and the weirdness of the future and I don’t think we’ve ever left that.

Cabaret Voltaire tour the UK for the last time in 2026 with Gazelle Twin