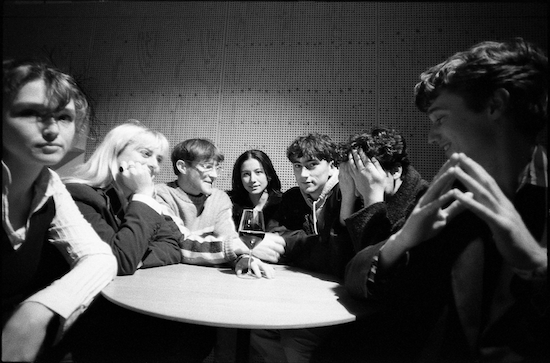

Band portraits by Benedicte Dacquin

Once in a blue moon, on the very, very rare occasion that a new band expresses joy that I have become a vocal fan of their music, I’m always quick to temper their happiness with a sour observation: “I don’t know what you’re looking so pleased about; this is just the start of your troubles.” Such can be the commercial, critical (and in some cases literal) kiss of death augured by my endorsement, that I can only start this feature by apologising to the band I currently believe to be the best in the entire world, Black Country, New Road.

If anything, the Cambridgeshire-by-way-of-London seven piece modern rock band haven’t been going out of their way to court any press attention at all, let alone mine: they said no to this interview twice before eventually agreeing. They may have only formed about 18 months ago but so far they haven’t really needed to do any press. Their road-tautened live shows, stupendously electrifying affairs that they are, have created all the intense word of mouth heat they’ve required.

Whether it’s being adequately reported on or not, there is something kicking off right now at the peripheries of rock music, which is so exciting that it’s in danger of dragging the centre outwards, while warping, inverting and destabilising its ecosystem (hopefully sloughing off some old fuckers in the process). There are a clutch of bands using a post punk and post hardcore framework to explore various other influences that run from acid folk to Krautrock via klezmer, jazz, funk and no wave, combined in odd new ways to create strange new affects. These bands are young but have amazing chops, and are often current or former music students (this being an acknowledgement primarily of the need for young musicians to have access to practice spaces that don’t cost money in which they can experiment and grow, rather than a comment on their privilege). But I’ve laid out why I think this is happening and what I think it means elsewhere, and all I really want to add here is that I think BC,NR are key to what I’m talking about, alongside Rough Trade signings, Black Midi.

Most of the musicians involved in Black Country, New Road were previously in an ill-starred band called Nervous Conditions who formed in an East Cambridgeshire village in 2014, when some of them were still at school. To call their kinetic shows exciting would be a gross understatement. Their double-drummer line-up added an air of The Fall in 1982 or NoMeansNo in 1993 to the rancorous Beefheartian clangour and Bad Seeds swagger. And their glittering brilliance, where grindcore fury and hectoring scorn could give way to placid beauty at the drop of a hat, had not gone unnoticed. Not last winter but the winter before, it was nearly impossible to get into their gigs for A&R scouts, but then, in January 2018, singer Connor Browne was accused of sexual assault by two separate people via a social media post and the band split up a few days later. In a statement, Browne apologised to the two women who made the accusations but also to his band mates, saying that they were “wholly unaware of any allegations that might have been made” against him. And that was that.

Within months, and with barely any fanfare, a new group with a similar line up was gigging hard around London and the South East. Browne was gone and former guitarist Isaac Wood was now the frontman, they’d lost Johnny Pyke, one of the drummers, but kept Charlie Wayne behind the kit. And everyone else filled the same roles: Tyler Hyde on bass, Lewis Evans on saxophone, May Kershaw on synths and Georgia Ellery of Jockstrap on violin. (In more recent months they’ve picked up a second guitarist, Luke Mark.)

But if the line-ups were similar, as bands they sounded notably (if not entirely) different. BC,NR it was obvious, even after a handful of shows, were the better proposition. For me, it took their actual existence to help me articulate the few small musical issues I had with Nervous Conditions. Whereas the obstreperous and declamatory, front and centre Browne was clearly operating from a place of sincere, if somewhat overpowering, Fall-fanship, it was harder to pinpoint exactly what was going on with Wood – stage left and in the shadows – who often appeared to be undergoing some kind of literary psychotic break or transcendent Damascene fugue during early BC,NR shows, let alone where his sonic inspirations were coming from.

If I’m trying to sidestep the usual journalistic pitfall of describing a band I really like in terms of who they sound like, I often try and imagine them as a pile of books on a bedside cabinet. This makes even more sense with BC,NR as there’s clearly some kind of literary bent at work here. I’m not just referring to the already commented on sprechgesang (spoke sung) vocals, which suggest narrative songwriting, with lyrics that may be partly or wholly fictional, rather than someone merely singing about their personal experiences. There is also the breadth of writerly technique to take into account, with Wood switching between prose, blank verse and rhyming couplets with ease, often in the space of one song. He employs multiple narratives with shifting narrative perspectives related by wholly unreliable narrators and various postmodern techniques, such as meta-textual references to other songs. In their debut single, ‘Athen’s France’, released earlier this year by Speedy Wunderground, Wood name checks two singles in close succession, the 100 million streams and counting ‘Thank U, Next’ by Ariana Grade and the possibly slightly less well known ‘The Theme From Failure Part 1′ – a song released by the singer himself during the same year under his solo guise as The Guest. These and other sure-footed juxtapositions, both lyrical and musical, provide the first lot of clues about where Black Country, New Road are coming from.

Over the course of what became this interview I met Isaac Wood once in a West End bar just to be rebuffed, I ran into him at gigs on a couple of other occasions and then, after a change of heart, met most of the band round at a flatshare in Kentish Town where they cooked me tea. (For the record, they made excellent fish burritos and got me into watching Bojack Horseman: I would highly recommend going round to their house for tea in the unlikely event the opportunity comes up. You should consider this my five-star Trip Advisor rating.) Half of this interview was then carried out later by email, question by question, rather than in a questionnaire format and then finished off face to face with Wood in Kings Cross, at the Lexington venue where I used to work. And if anyone is wondering if I normally go to this much trouble in order to do an introducing feature on a new band, the answer is most definitely, no I don’t, but I’ll leave you to figure out why I made an exception in this instance. The band were all happy to let Isaac do the talking in this instance and, after giving it a lot of consideration, I elected to not ask them any additional questions about Nervous Conditions.

When I asked him if he’d been a writer of any stripe – a diary keeper, a teenage poet, an impassioned essayist, a keyboard warrior – before he became a songwriter he replied: “I don’t have a particularly long or rich history with writing words. There were a few early attempts but the first thing I remember seriously committing to writing was ‘Theme From Failure Pt.1’ in mid-2018, the year of fear.”

The song is a hilariously arch, meta-modern piece of synth pop with the lyrics: "I asked every girl I’d ever slept with to rate my performance and the results were horrifying.” It’s a truly terrifying idea – so bad, so ill thought out, so destined to end in disaster and shame that it belongs in Greek mythology or a book about the collapse of the Persian empire.

Wood is keen to put a tiny stretch of clear blue air between him and the song’s narrator: “I did about 80% of the things mentioned in that song but that was not one of them. ‘Theme From Failure’ is proof that you can find 50 ways to say the exact same thing.”

Speaking about lyrical influence he namechecks peers, or people he looks up to, who can be found in his own micro-scene centred around The Windmill pub in Brixton and the Speedy Wunderground label. He specifically heaps praise on Jerskin Fendrix: “He was totally formative for me. There were a lot of musical concepts that I had barely begun to grasp when doing my own music that were already fully formed in Jerskin’s set by the time I first saw him. What he did was funny and very moving but never particularly naff. I think the most accurate description of our relationship would be that I am his nephew.” Likewise he has a lot of praise for the barely Googleable Famous and James Martin (aka Ronald Rodman). A few weeks after the interview is over, he emails me to rave about ‘Don’t Make Friends With Good People’ by Kiran Leonard, a track he’s currently playing on repeat. As for literary influences he initially offers a faux-callow: “Obviously I have read some books and they have had some uncertain influence on the words too.”

When pressed he namechecks Thomas Pynchon and Kurt Vonnegut, two novelists he was reading a couple of years ago. When I mention their lack of respect for a high and low art boundary, he offers a not-very callow corrective: “It’s an issue that some people don’t respect that boundary but slightly more successful writers respect it, understand it and choose to subvert it or manipulate it, which is to an end rather than just doing it for the sake of it. They’re not doing it to make some boring generalising point about culture but to actually say something emotionally resonant that people can relate to. We all experience things that you could deem high or low in terms of cultural worth but when those things intersect or when the boundary doesn’t feel like it exists, during the point when that boundary is eradicated, then it becomes part of that poignancy and part of the emotional resonance of that moment. That is something which, if it can be described accurately, can be incredibly impactful and I’m interested in this because of writers like Vonnegut.”

Which is me told.

Early literary experiments of his own include ‘Kendall Jenner’, a Black Country, New Road song with an odd, James Ellroy-scripting-Mulholland Drive vibe, which features a narrator who gets strong-handed into visiting the reality TV star in a hotel penthouse suite against their will. Once inside Jenner complains of ennui ("Baby I’m all strung out on Netflix and 5HTP/ My whole adolescence has been broadcast on TV/ I can’t feel a thing when anybody touches me/ And I’m lighter than air when I take off all my jewellery") before stabbing and killing herself. The pay off line – "Kendall Jenner is bleeding all over this couch/ It’s gonna take a lot of bleach to get these stains out", I took to be a nod at the complicity of the viewer when watching reality TV but he’s on hand, again, to correct me: “I just wanted to try out a narrative device that I thought would be entertaining. The end of the piece of music was a pretty stark contrast to the previous section, and I thought the story needed some sort of climax, so it ends, like many things, with a death. It’s not really intended to be any wider commentary about her position or place, nor on her fans or viewers, I’ve always enjoyed keeping up with her and her family’s goings on and find them all to be quite entertaining people and good celebrities.”

It was, however, an early experiment, and one he now expresses some reservations about: “It was my first attempt at a straight-up narrative piece and possibly a little bait looking back on those words now.” Narrative storytelling or not, I ask him if he’s aware that simply by singing about such things, he’s running the risk of being labelled a misogynist, and initially he sounds dismayed: “I hadn’t really considered that – I hope I’m not putting that idea across.”

He returns to this sentiment later in the interview when I ask him if he ever adopts a persona (or mask) which is very close to his actual self when songwriting. I mention the technique used by such writers of autofiction as Karl Ove Knausgard or the comic Stewart Lee, who adopts subtly different character traits depending on whether he’s writing about politics or performing stand up: “With the first songs (‘Athen’s France’, ‘Sunglasses’), I’ve been focused on the pathetic and cynical thoughts that start appearing when we start to defend ourselves in times of great insecurity. So I guess yes – [I have been] writing in the character of the inner dude man relentlessly defending himself and re-writing his flaws and missteps as other people’s mistakes. It’s tricky and I’m sure it doesn’t really translate well sometimes… I definitely regret what could be perceived as a slightly reductive and one-dimensional portrayal of women in those early songs for example.”

Swivel-eyed break-up song that digs into uncomfortably raw territory or not, ‘Sunglasses’, for what it’s worth, is my track of the year. It’s form marches in lockstep with its function and meaning all the way through its implacable nine-minute running time. Given the intensity of the track, that speaks of bruised egos, jealously, insecurity, and all the rest of it, unsurprisingly Wood tries to duck talking about it in concrete terms. When pressed he mentions a “difficult experience” that a friend he’s no longer in touch with had as regards source material: “It’s written from the perspective of a particular voice which is inside a lot of people; a voice that can feel incredibly pessimistic and arrogant. One thing that I think is good about the song is something that struck me in a similar way about Father John Misty. I think the first time a lot of people hear ‘Sunglasses’ they find it grating and abrasive, and not just in the sonic way. It’s actually voiced in quite an irritating way with these quite stupid inflections which are so whiny, affected and performative, it’s quite over the top. I get quite irritated listening to it so I can imagine a lot of other people will as well.”

I know it’s beholden on me to suggest to him that he’s mistaken but really, from my point of view, he really is. In the history of vocalists that I really like, very few of them could have sung their way out of a wet paper bag if their lives depended on it – if we’re talking in strictly technical terms. It’s obviously an odd state of affairs but if you’re talking about a very wide and loosely defined continuum of post punk and post punk adjacent singers, the ones who can actually carry a tune proficiently – Ian McCulloch, David Bowie and Scott Walker for example – are the exceptions rather than the rule. I very vividly remember hating so many singers who are now my favourites when I first heard them… Mark E Smith, Sioux, Ian Curtis, Iggy Pop, Bernard Sumner… Most of them go way beyond the idea of vocals being distinctive and into the arena of jouissance.

He agrees begrudgingly: “Hopefully if they listen to the vocals a lot the listener’s experience of it will flip at some point. Then they fetishise it, then they start to enjoy it.”

When I ask how the song got its unusual arrangement, he gets exasperated: “I think it’s pretty blatantly set up musically to follow a narrative in terms of what happens in the story. Come on… I don’t have to explain this.”

I tell him that actually he does have to explain it if he doesn’t want me to put words in his mouth: “Ok, well it starts one way, something happens and then it ends another way and the music follows that.”

He sighs and adds: “And whether it works or not is for you to decide. But I find this way of writing effective especially if I can’t write a genius pop chorus or something like that.”

But is he absolutely sure he can’t? It’s unfair of me to keep on going on about his age but he is actually dead young. He was still a teenager at the start of the year. He still has time, just about, to write his generation’s ‘Groove Is In The Heart’ or ‘Umbrella’ if he wants… The post post rock ‘You’re So Vain’ maybe…

He laughs: “Maybe. I’ll have to get some lessons in how to croon properly first though…”

Observing BC,NR in real life – a bunch of mates not long out of their teens, doing normal stuff, making fish burritos, talking about football, laughing about a cartoon alcoholic horse, cracking up at the way dads use stickies in text messages – I’m forced to admit that before I met them I was guilty of projecting onto them slightly. I had this idea of them being laureates of anxiety, simply because it fitted in neatly with some preconceived ideas I had about them being part of an emergent generation, with everything that implies. There is some anxiety in Wood’s song writing and the belting BPM of as-yet-unreleased hyper-klezmer wipe-out ‘Opus’ – “Everybody’s coming up. I guess I’m a little late to the party” – helps underline this, but poor mental health is not their USP. He says: “I wouldn’t consider anxiety a conscious influence of mine at all really – but it is often felt at times of great importance and times of great importance are naturally things we might choose to write or sing about. And during my delivery, I can simply find myself quite overwhelmed sometimes.”

If anything they’re still just trying stuff on for size to be honest. By the time they release an album – I ask about this but he’s charmingly evasive – I have a feeling it will contain mainly different songs than the ones that are in their set now. And my guess is they’ll sound slightly different as well. Even though, it was only written a year and a half ago, ‘Opus’, must already seem like it was the product of half a lifetime ago. Wood says: “It was the first thing we ever did. It would have been [written] at our first meet up after Nervous Conditions ended. We were in Dulwich round at a friend’s house and it just came out of a small get together and some improvising. We’ve not really done anything quite as fast since. It can be a little slice of enjoyment for the audience for a very brief period and a little slice of anxiety for the rest of us.”

He describes their initially odd-feeling name, as being like “propaganda”: “It’s like our very own ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ or tea-mug proclaiming that you don’t have to be crazy to work here but it helps. It basically describes a good way out of a bad place. Excited people sometimes claim to have lived near the road and I keep having to explain to them that it doesn’t exist.”

I think it’s important to note that their group is already firing the imaginations of young fans, even if sometimes concerning road accidents. One can only presume that during the first ever session, the one that produced ‘Opus’, there was some kind of discussion about how to differentiate the new group from the old one: “I can’t remember specifically how or when it was reached but I believe there was an understanding of what we collectively wanted to do with BC,NR. We had been doing the other group for two or three years and certainly wanted to employ a few of the things we had developed in that time. But of course there is the desire to try to make a different kind of music to that which came before and the current output is actually a little more at home for all of us – which is probably as a result of a slightly more collaborative writing process.”

Is there a specific song writing process though? It seems unfair to even mention this but a friend of mine said she got on the same train as BC,NR after leaving Sea Change Festival in Totnes heading back East and they were embroiled in some protracted argument over which carriage to sit in, which naturally made me assume that the songwriting process had the potential of being a very hotly contested thing.

He begs to differ: “There’s no real specific process but initial ideas are usually sketched out by Lewis and I, then the more harmonically-able members of the group augment those sketches with top lines and so on. Its then fleshed out and taken apart by the group as a whole and worked into something that satisfies all of us. At that point I’ll work out the theme and put together some words for the song. Despite what your hot intel suggests there are very rarely arguments during the writing process – there is a certain level of musical trust that has built up between us over time.”

And you can hear it clearly in the way the elements in the band’s sound are combined. This isn’t just rock music with some ‘exotic’ colouring agents for example. Given that two of the more obvious elements that are synthesised are the ostensibly very different – klezmer and post hardcore – it’s tempting to assume there are a number of ‘different camps’ in the band.

Wood breaks it down for me: “There are definitely some pockets of relative expertise. Georgia and Lewis both have a lot of experience playing klezmer music, Georgia currently performs with the Happy Bagel Klezmer Orkester and Lewis played with experienced klezmer musicians when he was much younger – they taught him how to improvise and this massively influenced his writing. May devotes the most time to classical disciplines and I own the most Arcade Fire albums. But it’s not a case of these influences battling one another for ground – we all share a passion for rock music and try to individually employ what we can to make the music something satisfactory.”

But let’s not beat around the bush here… this is Isaac Wood’s band isn’t it?

He is obscure rather than diplomatic in answer: “Black Country, New Road is ‘my band’ in the same sense that that Australian man in his crashed car was ‘just waiting for a mate’.”

Ignoring the fact I have no idea what he’s talking about I plough on. What kind of bandleader is he though? Benevolent man of the people; Stalinesque tyrant; ultra-relaxed liberal democrat who will get disappeared during the dead of night and replaced by an altogether more steely and morally ambiguous member of BC,NR…

The unlikely and equally impenetrable reply is: “I am widely respected like Vice President Al Gore.”

The only inconvenient truth about Black Country, New Road, for me at least isn’t that they’re not quite the absolute vanguard of newness that I secretly want them to be but simply that my wish for them to fulfil this role is typical of problematic old wallopers like me. They simply don’t sound like anyone else even if you can name most of the component parts – and that’s obviously more than adequate. Every time someone claims they sound ‘exactly’ like some other band – Slint, Joey Fat, Oxbow, Cows – it’s demonstrably easy to prove them wrong and, let’s have it straight, it’s not like these are obvious reference points in the first place even if they all deserve to be considered. I feel like pop culture is more rhizomatic now, there’s connectivity up the wazoo and it all works in strange and unpredictable ways. If someone wants to accuse BC,NR of being a Shellac knock-off, the first thing they have to consider is the klezmer and free improvisation with sax, strings and synths but then secondarily, their non-ironic immersion in global pop culture is also part of the mix. The unbearable lightness of Kendall Jenner; the ubiquitous relationship wrecking shadow cast by Kanye West; a precognisent glimpse at love’s failure lit by a large 4k TV showing “the best new six-part Danish crime drama”. But also an unmistakably savage satire of English parochialism: “And in a wall of photographs, in the downstairs second living room’s TV area‚ I become her father/ And complain of mediocre theatre in the daytime‚ and ice in single malt whiskey at night/ Of rising skirt hems‚ lowering IQs, and things just aren’t built like they used to be/ The absolute pinnacle of British engineering.”

Like their name suggests, there isn’t a destination in mind yet for Black Country, New Road, just velocity and sense of escape; a disaster narrowly averted, a hard earned sense of freedom. Absolute potential. I don’t want to jinx anything by making any great claims for this band (I’ve done enough merely by expressing an interest) but you should go and watch them play live very soon if you haven’t had the pleasure already; in any sane plane of existence 2020 will be their year.