"There had been a series of rapes in the underpass on the way to the station. Josie Long — who is a lovely woman — was playing The New Theatre. She said to me after the show: ‘So I have to walk past the abandoned shops, past the old factory with the broken windows, go through the underpass and then past the burnt-out pub to get to the train station? This area’s a little rapey, isn’t it?’ We said we’d walk back to the station with her."

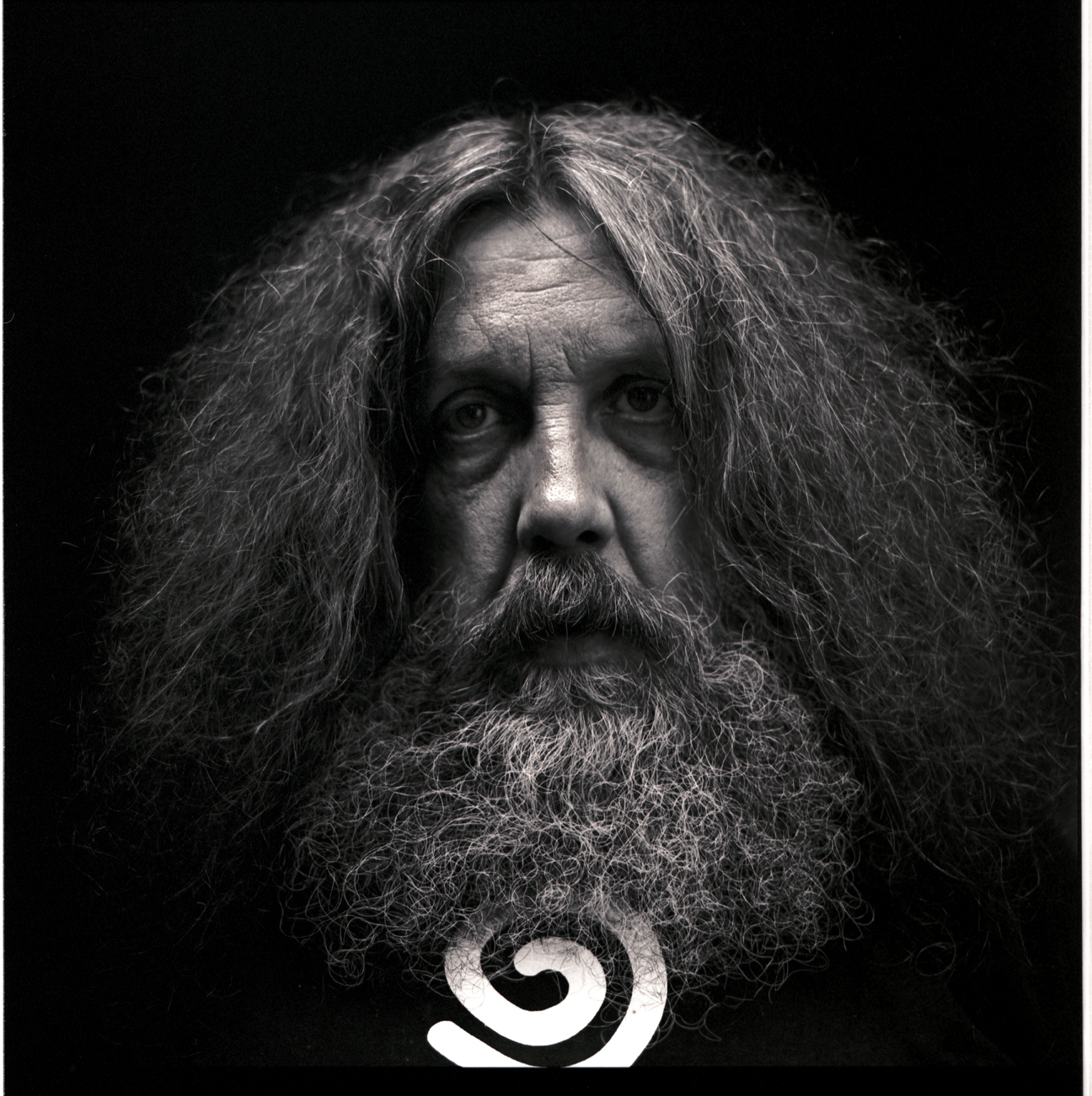

Alan Moore is holding court. He has a terrifying work ethic that belies the myth of laziness often lazily ascribed to his sub-cultural fringe of writers, anarchists, psycho-geographers, psychedelic bon vivants and occultists, and he doesn’t usually have much time for interviews. This said, he is extremely good company and you can tell he enjoys playing the expansive raconteur all the more because he gets little opportunity to indulge himself.

And while he is reassuringly genial, he is much bigger, more leonine and prestidigitatoresque than photos make out. He looks more like a Brian Bolland drawing of himself than himself. Even the permanently smouldering joints on which he tokes are much fatter and longer than you’d credit — although filled from a soft, dark block of Moroccan hashish resin the size of a cigarette packet, not some discombobulating new strain of super skunk.

He only darkens during a brief but measured aside about sexual assaults in the area and the way in which a visiting comedian dealt with the theme during a recent stand-up routine. Then he reveals a steeliness more in keeping with his status as the only comic book writer in the world who is regularly talked of in the same terms as some of the great novelists of the late 20th Century and beyond. Part of this reputation is built on the 1986 comic series turned graphic novel Watchmen, which indelibly changed the face of its industry and produced a leap forward in process and potential equivalent to those realised by Citizen Kane. That’s not bad work for a lad who was kicked out of school while a teenager for dealing acid. He was turned-on by the hip psychedelic counterculture of the late-sixties and became a performance poet in a local multi-media collective, the Arts Lab. He was also an autodidact who pursued his love for imported American comics (which at the time were so worthless they were used as ballast in trans-Atlantic ships) into writing strips for Sounds, Doctor Who Weekly and then 2000 AD.

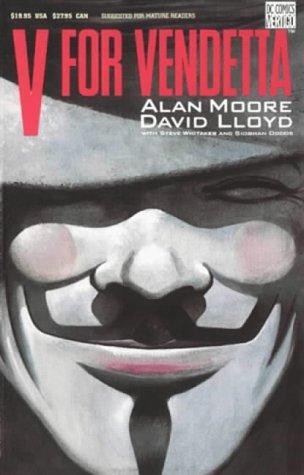

Since his big break writing Swamp Thing in 1983, he has remained at the top of his field (completely in critical terms and mainly in commercial terms; some of his most ambitious work stalled before completion with the astounding Big Numbers frustratingly only reaching two issues), and he has done so by consistently kicking against the pricks. From insisting on having strong female protagonists (The Ballad Of Halo Jones), to writing about anarchy and insurrection (V For Vendetta), to exposing the illusory nature of modern histories (From Hell), to making pornography (Lost Girls), to introducing a discourse on perceptions of reality and free will into the ‘low’ form of the superhero comic (Watchmen) while maintaining a fiercely unpretentious and by turns disturbing, warm, profound and, at times, hilarious tone; he has booted down numerous doors… some of which others are yet to follow him through.

As he carries on the anecdote, laying mercilessly into another figure, recognisable by his long mane of hair, distinctive beard and black goth/punk/metal clothing, you get the sense that he’s not much interested in fashion but is keenly interested in how people present themselves to the world. "A few days later we had that Russell Brand here doing stand up at the same theatre and he started doing a routine about the local rapes," he says. "Wouldn’t stop, even though it was fresh in everyone’s mind. Very daring of him."

Whatever he talks about, it isn’t long before he returns to the subject of Northampton. This town where Moore (also a poet, illustrator, magazine publisher, magician, spoken word artist, smoker, toker, mid-afternoon joker) was born in 1953 may be directly in the middle of the country, but it is not Middle England. Anyone who lives in Leith or St Helens will instinctively know this place. Anyone from Gillingham or Swansea will recognise its pedestrianised town centre; streets pock-marked with boarded-up units, vacant in the face of competition from rapacious out of town retail parks, their core industries long since gone and replaced with an insubstantial service industry varnish. Places like Harlow, where the streets have no names, just numbers.

"So next time Brand comes down here, I’m going to rape him. And then phone his granddad up live on air to tell him about it."

He gamely signals that, of course, he’s joking, just in case we are the sort to judge him unfairly on this and not on his body of work. And this work, which has also taken in ritual magic, the worship of a Roman sock puppet deity called Glycon and a subversive underground magazine called Dodgem Logic, has recently come full circle. He has returned to the spirit of the Arts Lab by releasing the spoken word piece Unearthing on LP and CD along with music by Mike Patton, Justin Broadrick, Stuart Braithwaite, Zach Hill and Crook & Flail, accompanied by a book of photographs by Mitch Jenkins. The piece was originally commissioned by psycho-geographer/writer Iain Sinclair for his anthology London: City Of Disappearances (2006) and concerns his friend, fellow comics writer and cultist, Steve Moore. Thirty-five years ago, Steve (no relation) bought an ornamental sword for use in a magic ritual, which triggered off an obsession with the Greek moon goddess Selene and the arcane history of his life-long home, Shooter’s Hill in southeast London.

It’s almost a luxury to be able to smoke indoors these days.

Alan Moore: It’s very civilised. I’m not keen on having to go to places where you have to stand outside to have a smoke. People complain about passive smoking but they don’t realise that my passive smoke has a measurable retail value. I’m thinking about charging people to stand next to me. I smoke indoors. Although since I got married to Melinda [Gebbie, co-creator of Lost Girls], and she’s moved in with me, I have relented and will open a window now.

Do you think, on the quiet, you’re a lot more of a traditional Englishman than people might presume?

AM: That depends on which English tradition you’re going for. I like to think of myself as a traditional Englishman, at least in so far as the traditions of Northampton go. But we have been on somebody’s shit list since about 1263 and we only made matters worse by supporting Cromwell during the Civil War and making the boots for the New Model Army — for which I don’t think we were even paid! And then, of course, Cromwell turned out to be even worse than Charles I and he only lasted for 15 years before we had Charles II back on the throne. He didn’t look favourably on us and he pulled down our castle. I guess he took it to heart that ‘we’ had chopped his dad’s head off.

Does this ‘traditionalism’ tie in with your mistrust of the internet? I find it slightly odd that someone who is renowned for working in speculative fiction and near-future writing isn’t interested in a tool with such potential.

AM: I’m practically Amish when it comes down to it. I practically mistrust any technology that came after the buggy. What I tend to think is that the internet is fine for everyone else in the world. I can see that it may have some disadvantages. In fact, I can see a few problems arising from it, but, by and large… everybody in the entire world apart from me uses the internet and seems to get on quite well with it. For my part, I don’t want to be connected to that all-pervasive kind of cyber culture any more than I want to be connected to the physical world that is around me, more than I can help it [laughs]. I’m largely a solitary creature, just by nature and by my work. That said, I venture out into town, but I very seldom leave Northampton.

Is it important that not only is Northampton close to the physical centre of the UK but, as it has gone through the last two or three decades, it now looks like a lot of other places in Britain with its pedestrianised shopping centre, chain stores moving in, and local family-run businesses closing down?

AM: That’s it. You could even be forgiven for thinking that some of these councils are actually trying to divert the life and activity away from town centres to the more profitable retail parks which are surrounding most of our conurbations nowadays. That certainly seems to be the case in Northampton. We’re all practically living in the same place. There has been a great levelling. We have the same brand names reiterated in all of our shop fronts; the same chain stores in every town. All of them have the surveillance cameras, although probably not to the same degree to which we have them here. We’ve got ones that talk. They say things like, ‘Pick that cigarette butt up. Yes, you, the one in the anorak.’ It’s this kind of sub-Orwellian theatrics that just make people more annoyed than anything else. They don’t alter crime, just people’s happiness.

It’s been noted before that you successfully predicted the pervasive intrusion of CCTV cameras into all aspects of urban living as far back as 1982, when you started V For Vendetta. I guess you only have to look at the graffiti of figures such as Banksy and other loosely anti-capitalist aligned artists, and then onto late-adopters such as bands like Hard-Fi, to see that, two decades later, it has practically become a great pop culture icon of the times.

AM: There are an interesting number of people turning up at protests these days dressed as V [Guy Fawkes mask-wearing protagonist of V For Vendetta]. I know there is the Anonymous Group down the bottom of Tottenham Court Road barracking the scientologists [who sometimes adopt his disguise]… a good bunch of lads and lasses! But I’ve also seen some pictures recently from the Climate Change Summits and the anti-globalisation demos and there appears to be a growing phalanx of people wearing Guy Fawkes masks and wigs.

It’s handy, I guess, that not only does it tie in morally, philosophically and politically, but it also looks pretty fucking cool as well, right?

AM: It’s a pretty good look, isn’t it? And of course it preserves your identity. Everybody is becoming [a superhero]. In the past I’ve tried to say, ‘Look, we are all crappy superheroes,’ because personal computers and mobile phone devices are things that only Bat Man and Mr Fantastic would have owned back in the sixties. We’ve all got this immense power and we’re still sat at home watching pornography and buying scratch cards. We’re rubbish, even though we are as gods. I think the idea that we can all be superheroes if we want might still be contagious, like in V For Vendetta. I’ve heard of urban superheroes springing up across the world. I think there’s one in London called Angle-grinder Man…

Ha ha ha!

AM: I think he removes clamps from cars and things like that. They have them in America as well, apparently. And like in the same way serial killers would be caught with The Bible on them or a copy of John Fowles’s The Collector, there is a common link between vigilante heroes: all these little urban superheroes have copies of Watchmen!

Have you turned your back on superheroes now?

AM: I’m interested in the superhero in real life, but not the comic book version. I’ve had some distancing thoughts about them recently. I’ve come to the conclusion that what superheroes might be — in their current incarnation, at least — is a symbol of American reluctance to involve themselves in any kind of conflict without massive tactical superiority. I think this is the same whether you have the advantage of carpet bombing from altitude or if you come from the planet Krypton as a baby and have increased powers in Earth’s lower gravity. That’s not what superheroes meant to me when I was a kid. To me, they represented a wellspring of the imagination. Superman had a dog in a cape! He had a city in a bottle! It was wonderful stuff for a seven-year-old boy to think about. But I suspect that a lot of superheroes now are basically about the unfair fight. You know: people wouldn’t bully me if I could turn into the Hulk.

Your latest project Unearthing has gone through a number of different stages, starting off as a piece for an anthology put together by the pyschogeographer Iain Sinclair to how it stands now with these amazing photos and music by great musicians, along with yourself doing spoken word which is like performance poetry. I was wondering how much you’ve come full circle and returned to your days back in the Arts Lab in the late-sixties.

AM: Very much so. I suppose it could be argued that I’d never really gotten away from the Arts Lab, but certainly over this last year I have very much returned to my roots. The multi-media explosion of Unearthing rather took me by surprise, because it was such a strange project to begin with. It all really commenced with Steve Moore himself — the subject of the writing. Back in 1976 he bought a Chinese coin sword made of 108 coins all tied together and used it in this very simple magical ritual which he came up with on the spot. He used it to ask for guidance and perhaps a confirming dream. The next day, he woke up with a voice in his ear saying the word ‘Endymion’, which, he later found out, was the title of a John Keats poem. This started the bizarre course that Steve’s life would take in many respects. It began his unusual relationship with Selene, the Greek Moon Goddess. So, in 2004, when Iain Sinclair asked if I wanted to contribute something to his London: City Of Disappearances book, I had something to write about. I’m always a sucker for anything that Iain suggests, really.

Is Unearthing a work of psychogeography?

AM: It’s more of a human excavation than the excavation of a place, but because Steve Moore has lived his entire life in one house on top of Shooter’s Hill and he currently sleeps no more than four paces from the spot where he was born, it does become a work of psychogeography as well. So we do go very thoroughly into what Shooter’s Hill is.

The etymology of the place name?

AM: Absolutely. Well, right back to the basic geology of how it formed. Apparently it was just because of a chalk fault that collapsed on the north side of the hill and that’s what created the Thames Valley. So without that, no river Thames, no London. And yet it’s this fairly isolated little hill, and there are lots of strange little places on it. We look into the place, but it’s more an excavation of Steve’s peculiar life which crosses into all sorts of different areas and crosses over with my life to a certain degree. It was certainly an odd little story that was self-referential. I’ve often found that if you write self-referential stories that feedback into your actual life then all sorts of weird things start to happen, or at least appear to start happening. Then Mitch Jenkins called round. I hadn’t seen Mitch for years, but he told me he’d got to a point in his photography career where he was pretty much at the top of his field. He was bored of getting all these commissions to re-touch the irises of the latest American TV star, so he asked if I had any pieces of text that he might be able to turn into a series of photos. The only thing I had lying round was Unearthing. I said, ‘Look, this is a bit big and unwieldy but there might be something in there.’ Mitch came back in a state of excitement, saying that he wanted to realise it as this huge book of photographs. I said, ‘Sounds good to me.’

How did it expand from that into music?

AM: Mitch said he’d been talking to the people at Lex records and they suggested all these wonderful musicians, which sounded fantastic. I came to this studio and recorded the various passages which the music was then composed around.

The piece has this ending where you describe sending the first draft of the piece to Steve and the instructions that he had to follow on opening the envelope. You read it, or listen to it, for the first time with him…

AM: He first read it exactly as it’s described in Unearthing itself. I sent it to him in an envelope with the ending already written that was actually telling him to go out for a walk around this neighbourhood, and he did. He went all the way round to the burial ground and stood with his back to it, as I’d already described in my creepy self-referential story. He said he felt very weird.

Well, you would, wouldn’t you!?

AM: He did actually feel a shudder run through him when he was standing with his back to the burial ground and since then his life has changed drastically. Unearthing itself was a big part of that in that there were people Steve had known for decades, and lived with in the case of his brother, who did not know how very, very strange he is. The thwarted love interest in the story read it and she was quite upset by it at first, but their relationship and their friendship recovered and became a lot stronger and healthier because of it. Steve has a new love interest. His brother contracted motor neurone disease just after Unearthing had come out and a couple of weeks ago Steve finally buried his ashes in the back garden. I was there with a number of the characters from the story. And, yes, this will eventually lead to a sequel. I have told Steve that I want to write a story called Earthing…

Would it be right to say that he’s your best friend and he’s been crucial to your career in a lot of ways? How did you first meet him?

AM: Oh yeah. Well, this was a different world, a long time ago. It would have been around 1967, so I would have been 13 and I was a comic fan. Every Saturday I’d go out and buy all of the Marvel or DC comics that had been shipped over from the States as ballast. And I would also buy the very few interesting British comics that were around then, which were mainly published by Odhams. They used to re-print black and white versions of the American Marvel titles. And there was an announcement in one of the issues of Fantastic that their new tea boy, Sunny Steve Moore, had got together with some friends and had put on the first UK comic convention. Now, I was probably too young to attend that, but I became an associate member, which meant that I paid some money and got all the literature. And in one of the fanzines that came in my introductory package there was an actual address for Steve Moore. I basically began stalking him and wrote him a couple of letters and we began a correspondence that has lasted for years. When I was starting out he was an invaluable help. When I decided to move from being a cartoonist to being a writer, it was Steve who read through my early scripts and told me to lose half the words and gave me a lot of pointers on how to do it. And then later it was him who inspired me to become a practising magician. In many ways, he’s completely ruined my life!

This isn’t the first musical project you’ve done. In the past, you’ve been associated with David J of Bauhaus and have even released records yourself. Is there any sense in which you are a frustrated rock star?

AM: Well, yeah. I mean, back in the Arts Lab days all I wanted to do was to be able to support myself through being creative. There was a time when I thought I might be a superstar poet, then I realised that was an oxymoron and that would never happen. Then I thought ‘rock star’, until I realised that I couldn’t play an instrument, so I tended to gravitate towards writing and drawing. That just seemed to be the easy way in although, yes, I have been involved with various musical projects — The Sinister Ducks, then with [cult Northampton psych musician] Mr Liquorice of The Mystery Guests and then The Emperors of Ice Cream.

All of these names have a very psych rock feel to them.

AM: Yeah. I am a huge exponent of psychedelic culture. I don’t care whether it’s fashionable or not but the ethos that was around [in the late-sixties] was an incredibly productive and benign one. I suppose that a lot of my work since then has been soldiering on with the same basic agenda.

As much as this could either be a cliché or a truism: to what extent do you feel that taking LSD as a teenager acted as a catalyst or a key as it were?

AM: Of course you can never say what would have happened if it had gone otherwise. I would say that it had a tremendous impact on my life. When I first took acid, I saw a quality of

hallucination that was only like that for a few years. Very much like a Martin Sharp [of Oz magazine] illustration. It was very liquid and drifting. But then, a few years later — I’m sure that the acid was exactly the same — it was the landscape that had changed. The experience had become more crystalline and hard-edged. A bit more paranoid. But, yes, it made me realise that actually reality was a state of mind and that, as your mind could change, so could your reality. This was something that would have a big influence on my later thinking, and I also think I realised that my perceptions about art and writing and music when I was in those sorts of states were wonderful. But it didn’t mean that I liked everything — far from it. I became quite critically acute, but I would enjoy the piece of art, whatever it was, on a much more profound and glowing level. So I think I probably resolved to try and write or draw or create for people in the same kind of condition as I probably was when I’d created those words. It’s a bit like Jason Spaceman and Sonic Boom from Spacemen 3 back in the day when they wrote ‘Taking Drugs To Make Music To Take Drugs To’. I thought, ‘Yeah, that’s an elegant formula and I’m sure that an awful lot of art in the history of the world has been created in this way.’ I’m sure that’s what Wilkie Collins was doing and I’m sure that’s what Samuel Taylor Coleridge was doing.

Did you ever see the really bad side of acid? I don’t just mean feeling a bit weird or paranoid, but having the full-blown simulacra of paranoid schizophrenia?

AM: Not quite that bad, but I did have plenty of bad trips. I laid off the acid around the time that I got expelled from school. I’d already done 50 or 60 trips in a year up to that point and I was probably starting to have some strange ideas. But this was only ever recreational. In the West, it’s always going to be in the context of getting out of your head. Say in the case of eighties’ rave culture… you would get kids going to raves and having a blissful experience — an experience of satori [Buddhist term for enlightenment]. But after the weekend was over, they would have to go back to the council estates that they were trying to escape from. They were still there. And for some of them a chasm opened up between their desire and their circumstances that they fell into and didn’t get back out of.

Do you still take acid?

AM: I take magic mushrooms. The first time I combined them with a rudimentary magical ritual… well, that was the eye-opener. I suddenly realised that the combination made the magic work and made the drug much, much stronger and more profound. And since then I’ve only taken mushrooms in ritual circumstances. There just doesn’t seem to be any point in doing it otherwise.

You’re proud of your status as a hipster. Do you regret the way it’s become a disparaging, pejorative term now?

AM: Has it? Yeah, that’s probably true. It used to be a fashion statement, but it was information as a fashion statement which is probably going to do you more good than the clothing you wear. I got an incredible education starting from the point at which I was thrown out of school. Now, I could probably hold my own intellectually with most people who have had university or college educations. And indeed some of them will have done courses on my books. So, despite the fact my ‘education’ ended at 16, I had hipsterism, which was wanting to be hip, and that led me to read this incredibly diverse array of books on science, mysticism, science fiction, literature, art… I would find out about these movements that I had heard about, and it’s given me a pretty comprehensive education. Now I am an autodidact, which is a great word… I learned it myself.

I guess if there’s one thing that pushed your career forward more than any other thing then it was the 12 Watchmen comics. It was a watershed in how people looked at comics in general and shifted them into becoming acceptable for adults to read them (as long as they were referred to as graphic novels, of course). But if Watchmen kicked these particular doors off their hinges, why haven’t people flooded into the room?

AM: Er, well, I don’t know. Initially Watchmen gained a lot of its readership because it was taking an unusual look at superheroes, but actually it was more about redefining comics than it was about redefining one particular genre. I think both me and Dave Gibbons [artist] had a lot of knowledge about that scene and we were able to take it and change it around to our advantage. And, as you say, there hasn’t been a more sophisticated comic released in the 25 years since, which I find profoundly depressing, because it was intended to be something that expanded the possibilities of comics rather than what it has apparently become — a massive psychological stumbling block that the rest of the industry has yet to find a way round.

It did codify a lot of things.

AM: Well, yeah. It wasn’t necessarily planned at the time. We just intended to do a really good superhero book and then when we got to issue three, we suddenly realised that we potentially had something much bigger on our hands. Things like From Hell or Lost Girls are in some ways as complex and as subtle as Watchmen; it’s just that they’re not in as mainstream a genre as superheroes. You know, I would have thought that sex would have been a more mainstream preoccupation than superheroes but… apparently not! But, you know, at least the superhero thing is accessible to a wide variety of people. Whereas the brutality of From Hell or the sexuality of Lost Girls might be taking people into areas which they’re not comfortable with.

When originally reading Watchmen in comic form, I got the impression that the plot was being written as it went along.

AM: Yeah, absolutely. I think we got to issue three and, on the first page, there were all these things coming together; there was a new way of telling a story. We got the captions from the pirate comic [within the comic]. We got the balloon from the news vendor. The radiation sign was being screwed onto the wall on the other side of the street and they were all in this dance together. And then we thought, ‘This is new. This is good. We can take this further.’ And so with the next issue, we did that complicated thing with Dr Manhattan where we were slicing up time and rearranging it to achieve a kind of specific effect. And then we made the issue that was entirely symmetrical. Making all the scenes mirror each other from front to back. In every issue, we were trying to push it a bit further. We were thinking, ‘Are we doing something new with the storytelling? Are we doing something that hasn’t been seen before?’

You talked about the link between drugs and environment and culture before. In the mid-eighties, was it serendipity that you chose to use the smiley badge on the front cover of the comics just before it was adopted wholesale by acid house fans?

AM: That was just one of the many strange little coincidences that seemed to happen. When Watchmen came out, Tim Simenon from Bomb The Bass put a splash of jelly across one of the eyes in homage. But I can remember walking through town wearing an old Watchmen T-shirt with the sleeves ripped off and somebody shouting ‘Aciiieeeeeeed!’ at me from the other side of the street! Which was a pleasant and engaging experience! Working as a writer, one of the reasons I got into magic was because you start to notice this feedback between the writing and real life. It might be entirely in my head, but it seems significant. I mean, there was a conference last weekend in Northampton called Magus. It was academics coming from all over the world to talk about me and my work. So I went down with Melinda. They were nice people. One of the academics at this conference was saying that he was working on a book which was about Watchmen as a post-9/11 text. I can see what he means to a degree. One of my friends over there, Bob Morales, said he’d been talking to some people on Ground Zero on September 12, 2001 and he was asking them if they were alright and what it had been like. Two of them, independently of each other, said that they were just waiting for the authorities to find a giant alien sticking half way out of a wall.

Ha ha ha… fucking hell!

AM: There was that atmosphere of a cataclysmic event happening in New York, which I don’t think had been depicted previously… even in science fiction terms it was perhaps unimaginable! Yes, you do find that a lot of odd, little coincidences like that haunt your life.

This interview was originally published in the mighty pages of The Stool Pigeon. The latest issue – also featuring Robyn, Chrome Hoof, Mike Patton and Tamikrest – is out now. Click here for more information.

Unearthing is available for pre-order now. Tickets for the live show at the Old Vic Tunnel are also available from here.