CONTAINS SPOILERS

I guess it’s relevant from the off to out myself as the comic book equivalent of the much-maligned 10-CDs-a-year-guy. In fact, that’s not even close – these days, I pick up the occasional title from one man. And that man is Alan Moore.

Moore has come to occupy a unique position in both the comics world and the wider culture. He broke out of the superheroes ghetto (as was) in the 80s with a series of game-changing titles (Swamp Thing, Watchmen, V For Vendetta etc.) that redefined expectations of what a comic could be and unwittingly ushered in the concept of the ‘graphic novel’ (a term which Moore dislikes because it smacks of high-culture appropriation). For a while, Moore became an irregular presence in the media and found himself elevated to the level of modern day sage ("Alan Moore knows the score", as Pop Will Eat Itself put it), an impression not entirely dispelled by Moore’s resemblance to an Old Testament prophet and his pronouncement on his 40th birthday that he intended to become a ceremonial magician.

Moore isn’t so visible these days – though he’s still producing material at a rate of knots, most notably The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen – but he continues to cast a sizable shadow across the popular imagination. Much of the darkness and ‘adult themes’ that pervade modern superhero comics and films can be traced back to Moore’s seminal works, with the alternately straight-laced and campy antics of yore replaced by existential crises and heavy metaphors among the bone-crunching action. Ironically, given his vocal disavowal of all movie adaptations of his works, perhaps the biggest impact that Moore has had on the world at large is via the co-opting by various protest groups (Anonymous, Occupy etc.) of the smiling Guy Fawkes mask worn by the hero of V For Vendetta, as popularised by the 2006 film version.

For my own part, Moore first entered my consciousness during his mid-80s heyday when, as a callow teenager at university, I would haunt city-centre record and comics stores for want of anything better to do (such as writing essays on Descartes). I distinctly remember reading chapter VI of Watchmen (where the grim details of Rorschach’s origin are revealed) while listening to Big Black’s Atomizer for the first time, and having what can only be described as some kind of dark epiphany, as though suddenly given access to the "map of (a) violent new continent" that Rorschach describes (I was a serious-minded if impressionable young man). It’s hard to conjure the feeling now, but with the Cold War at its height (and televisual doomfests such as Threads turning up the chill factor), there was a background murmur of dread and fatalism that permeated that time – and Moore captured this mood horribly well with Watchmen‘s countdown to Armageddon and V For Vendetta‘s oppressive post-nuclear war society.

However, another title appeared during the 80s bearing Moore’s name that has become legendary among comic fans due to its subsequent unavailability for over 20 years. That title is Miracleman. As with many things in the Moore universe, the reasons for its disappearance and now finally its revival (courtesy of Marvel) are torturously complicated and need not delay us. Suffice to say that Moore has refused to have his name appear anywhere on the re-published issues, and is instead referred to only as ‘The Original Writer’ (which intentionally or otherwise makes Moore sound even more godlike than ever).

As was also the case with V for Vendetta, Miracleman originally started life in 1982 (prior to Moore’s breakthrough in the US with Swamp Thing) in the pages of Warrior magazine, which was a more grown-up version of long-running UK sci-fi comic 2000AD (which Moore also wrote for). Just to confuse matters further, when it appeared in Warrior, Miracleman was titled and based on the character of Marvelman, a British Superman knock-off from the 50s. Following Warrior‘s demise, Eclipse Comics re-printed and resumed the series in 1985, but was forced to change the name following pressure from Marvel Comics (ironically enough, as it now turns out). This was a serendipitous move though, as the key theme that the series ultimately explores is the idea of the superhero as a divine being (a theme that would also be integral to both Watchmen, as embodied by Dr. Manhattan, and Swamp Thing, where the titular hero is re-imagined as a plant elemental).

However, this mythical ‘lost’ series is perhaps best known as being Moore’s first attempt to inject a healthy dose of reality into the superhero genre. As with Watchmen, it tries to think through what would actually happen if beings with extraordinary superpowers walked among us. But as we will see, it comes to rather different conclusions than Watchmen.

Moore has said his inspiration for writing Miracleman was the idea of an ex-superhero wandering the streets, no longer able to remember his magic word. It’s a fantastic image (and one that resonates with anybody who no longer feels able to access the mental inspiration or physically stamina they once had), and it’s where the story proper starts, with freelance journalist Mike Moran plagued by bad dreams and migraines, tortured by something just out of reach.

But before we get there, there’s a very funny prologue set in the original Marvelman universe, where invaders from the future are preparing to wreak havoc on the innocent world of the 50s: "It is 1981, 25 years in our future, and Kommandant Garrer of the Science Gestapo is scheming with this atomic storm troopers…" In keeping with the traditional modus operandi of superhero comics, the ensuing battle adheres to the simple ‘might is right’/clobbering time school of conflict resolution, with the Miracleman Family (Miracleman plus Young Miracleman and Kid Miracleman) inevitably triumphant. And here Moore establishes another core theme of the series, a fear of progress and the nuclear gods that science has created – "Beware golden age of the past! A futuristic doom approaches!" (You could also read this as a veiled metaphor for Moore’s own agenda of attacking the old superhero conventions)

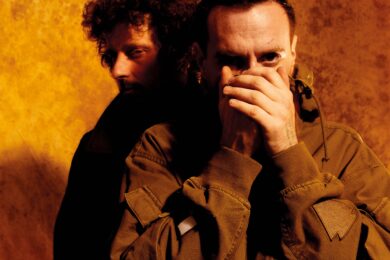

photo by David Ma

During a protest at a nuclear power station (of course), Moran finally remembers his word – Kimota! (that’s ‘Atomik’ backwards) – and transforms once again into Miracleman (drawn as an Aryan version of Paul Newman). It’s interesting that one of the first things he says is, "That’s right, I’m not human" – unlike the majority of other superheroes, there’s no pretence that he’s a mere mortal in tights: he is simply other. As the story progresses, the disconnect between the very human Moran and his alter ego – which isn’t helped by Miracleman impregnating his wife – becomes such that Moran ultimately elects to disappear altogether, unable to compete.

So what happens when gods walk the earth? Well, they have a bloody big scrap, of course, while we scuttle about like so many ants waiting to be crushed… Miracleman discovers that Kid Miracleman is also still very much alive (following the mysterious explosion in the 50s that erased Moran’s memory and killed Young Miracleman), and in the meantime has acquired great wealth ostensibly as the head of Sunburst Cybernetics. However, he soon drops his guard and reveals that absolute power has indeed corrupted him absolutely. Cue the first battle between the two, Kid Miracleman relishing the gruesome demise of any people who happen to be in their path. Miracleman initially prevails, but the series was notorious at the time for their final showdown, with its Goya-esque depictions of limbless, impaled victims (though the issue that caused the most controversy was the one that graphically featured the birth of Miracleman’s child – a dilated vagina clearly being more disturbing to the average comics fan than scenes of mass carnage).

Perhaps the cleverest sleight of hand that Moore pulls in this series is the new creation story he gives the Miracleman family. While they believe themselves to be superheroes, we discover that their adventures in the 50s have all taken place inside a virtual reality program, and that they are in fact genetically-engineered übermensch created using alien technology. And why have they been made? Not for the advancement of humanity, but as an ultimate weapon – "Imagine the mega-death potential of such a creature in an international conflict." But when the government agency running the project becomes fearful of losing control of the family as their conditioning starts to break down, they are lured into a trap in the real world rigged with an A-bomb in an attempt to destroy them. (Here’s an example of what happens when a weapon becomes self-aware)

The parallels with the Cold War world of the 80s are inescapable, with mankind teetering on the brink of total annihilation because of its scientific curiosity. In splitting the atom and acting as gods, we had only succeeded in creating monsters. Miracleman is ultimately about what happens when the monsters take control of their own destiny – which soon becomes our destiny. None too pleased to discover that his entire life has been a lie, Miracleman plays the role of the vengeful god, punishing those responsible. But things get really interesting/downright strange when he starts to think about the possibilities of his unique position. Why is it always just the bad guys who want to take over the world? Why not see if you can create heaven on earth instead..?

(It’s been noted before, but the apparent dichotomy between the two main series that Moore wrote for Warrior is intriguing: in V For Vendetta, the hero fights against a fascist power structure and espouses anarchy as a means of putting choice back into the hands of the people; in Miracleman, the hero seeks to establish a benign global dictatorship because mankind can’t be trusted to make its own decisions.)

Has it been worth the wait to see Miracleman re-published? Marvel is certainly hoping so, having run adverts for the recently released Book One: A Dream Of Flying (which collects the first four re-published issues plus assorted ephemera) in US cinemas and The New York Times. Leading with a (not exactly guaranteed to pull the punters in) quote from Time magazine – "A must-read for scholars of the genre" – and claiming that it’s "the series that redefined comics" might be somewhat over-stating the case, but for anybody who’s seriously interested in Moore’s imperial phase, it’s pretty much essential reading. Yes, there’s a lot of clunky expository text and purple prose here (though bear in mind that Moore was still in his 20s when he started this series, and the demands of writing a story originally split into 6-8 page chunks when published in Warrior are different from a long-form book), but Moore’s quicksilver imagination and innovative approach to structure are already much in evidence, as is his desire to push at the boundaries of what’s permissible/acceptable in comics.

For the casual comics reader (such as myself), Miracleman might not appear on the face of it to be as compelling or mainstream as Moore’s more well-known works. And unlike Watchmen and V For Vendetta, the artists change throughout the series, which means that it never develops the type of consistent visual grammar that helped make those titles so successful (though both Garry Leach and John Totleben do some great work). But for all that, Miracleman still fizzes with Moore’s conviction that comics can be so much more than just dumb entertainment. Though that’s certainly part of the equation, he wants to challenge us and make us think, just as he wants to thrill us and make us feel. He may have moved on a long time ago from this particular creation, but Miracleman is still a great place to experience The Original Writer in the raw.

For more information about all things Miracleman and to view scans from the original comics, check out the excellent Miraclemen.Info.