The Sentence is original. It is not original simply because of the story it tells. Like all science-fiction, you will be able to find precursors to its ideas in other work if you look hard enough. Likewise, there are other novels that have been written in a single sentence, although they perhaps lack a strong enough reason to take that form.

No, The Sentence is original because of the effect that reading it has on you. Its trance-inducing monosyllabic beat is irresistible, a literary four-four preventing you from leaving the page or the mind of the book’s narrator. No other style of writing has been able to take such high and lofty ideas and punch them down into the base of your lizard brain, where they belong. There is a PhD awaiting any neuroscience undergraduate with a copy of the book and access to a MRI scanner.

One unfortunate side effect of reading The Sentence is that it affects how you view the book you read after it. Unfortunately for me, I followed The Sentence by reading Steve Aylett’s Heart of the Original. Its central premise is that although we as a society claim to value originality, we actually find it upsetting and actively shun it. With hindsight, I have nothing but praise for Heart of the Original. It is a rich, wonderful and remarkable book, full of insights and ideas you will find nowhere else. If you were to read this book after watching a film like Jurassic World, or Star Wars: The Force Awakens, or Finding Dory – all beat-for-beat remakes of comfortable, familiar films that filmgoers flocked to in their millions – then Aylett’s argument seems unarguable. It’s only when you read his book after reading The Sentence that the problems start. It’s hard to take complaints about our failure to produce originality when you have just been drenched by originality in its purest, most self-evident form.

In Heart of the Original’s defence, The Sentence is something of an outlier in our broader culture: the reason why there is nothing else like this book is because there is no-one else like its author. Alistair Fruish is an alien. He arrived here from the Planet Ork in a large flying egg on a mission to understand our human ways. He thinks we haven’t realised. You’ll notice how he is intensely interested in everything. Pay him a visit and you will find him experimenting with ice baths, or bicycles that you row instead of pedal. There are strange items pickled in large jars around his home, which it is best not to ask about. This is all classic alien-scout behaviour. If humanity was able to produce people with their heads wired like Alistair’s, we would be living on Mars by now. I would love to see the file MI5 have on him.

Alistair is also intensely interested in language, to the extent that he wrote this entire novel in monosyllables because he wanted to truly understand them. This is not normal behaviour. Students of Artificial Intelligence will recognise it as the sort of thing you might expect a neural network to do, albeit a neural network programmed in a bit of a hurry. The Sentence should be a cold, abstract thing and yet, for all that Alistair Fruish is an alien supercomputer passing himself off as a Northamptonshire writer, this is also one of the most human stories you will have the good fortune to read. Its unnamed central character will become more real to you, in all his failings and strengths, than some people who have been in your life for years. Fruish’s obsessive desire to understand words and break them down into their constituent parts is all an excuse to understand a single human being by mercilessly breaking him down also. Fortunately this is not just an endless process of destruction. It does lead to the white light of understanding.

The Sentence is the sort of cultural bar raising that we so desperately need right now. I would hate to think that we lived in a world that failed to recognise cultural black swans like this when they emerged, or that this is a culture that turns its back on what is genuinely fresh and only payed it sufficient attention decades later, when it is judged safe and can no longer change us. I would hate to think that Steve Aylett was right, even though I know that Steve Aylett is probably right. My fear is that we cannot rely on our cultural gatekeepers to spread a work like this to all who need it. This is where you come in. If you find this powerful, which you will, you need to tell at least three people. You’ll know who. They will thank you for it.

It’s disturbing, but publishers and agents tell us that 73% of people who sit down to write a novel proceed to write some unnecessary shit about a vampire cop. I don’t know why this is, but I do know that if our culture is to aim higher then we need to embrace and celebrate the genuinely original. In artistic terms, ‘original’ means work that leads its audience’s consciousness into a new and unexplored state. This is what The Sentence does.

It is tempting to see The Sentence as the spirit of all books raising their game now that virtual reality threatens to take their place as our most vivid art form. So, please, spread the word. The last thing we want is for Alistair Fruish to return to Ork and report that humanity’s culture peaked at Finding Dory.

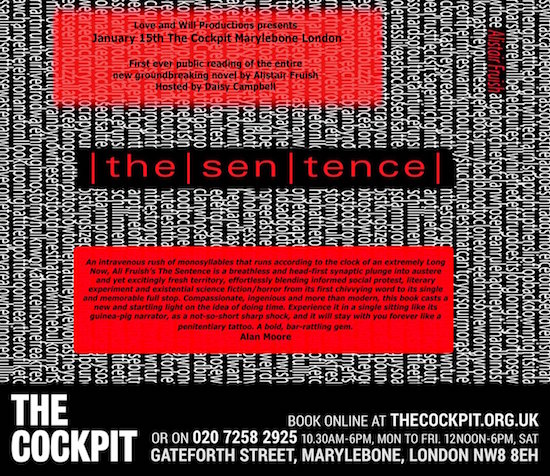

A live, non-stop reading of The Sentence by a group of actors will take place at The Cockpit in Marylebone (Gateforth Street, London NW8 8EH) on Saturday 15th January. Tickets available here.