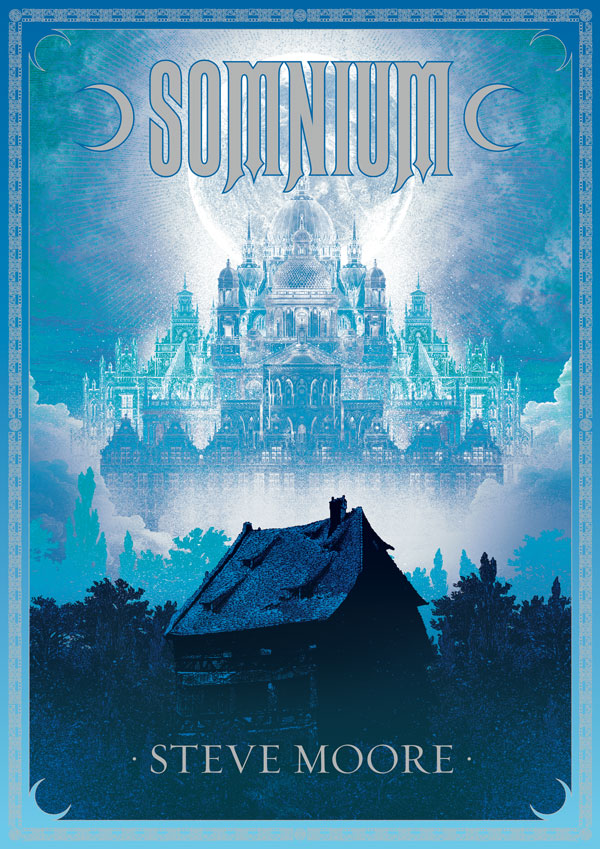

Alan Moore says it’s “a masterpiece”. Indeed. Steve Moore’s Somnium is a tour-de-force of playful majesty and magic, of style and of love. Spanning centuries, even aeons in its dreamworld, it ranges from Gothic novel through Elizabethan tragedy and mediaeval romance to piquant Decadence, all via the Greek myth of lunar goddess Selene and her mortal lover Endymion. It is nothing short of an epic love song to The Moon and of, as per her reflective nature, “the love the Moon has always had for Earthly things below”.

Those familiar with Alan Moore’s Unearthing, will know of his friend, mentor, and collaborator Steve Moore’s long obsession with the Moon-Goddess. In October 1976, having improvised a magic ritual with a Chinese coin sword, he awoke near dawn to hear an unexpected whisper which would provide a clue to his life’s work. Though, as Steve notes below, perhaps the lunar associations were always there. Unearthing takes us through Steve’s life – writing comics, studying and producing scholarly work on the I Ching, editing and contributing to Fortean Studies and Fortean Times – and also shows us the beginnings of Somnium, his debut novel.

In 1803, Christopher Morley travels to Shooter’s Hill to write the story of Endimion Lee, an Elizabethan knight who one evening at a crossroads finds himself transported to the dream palace of Somnium, there attended on by Diana Regina and her nymphs. The language throughout the book is exquisite, especially the poetic speech of the Moon-Goddess Diana and all within her realm. As Morley composes this tale (and others that Endimion Lee will find within Somnium’s fantastic library), he begins to notice strange and alluring similarities between it and his present circumstances. Not without their dangers and not entirely sure he isn’t going mad, Somnium expands outwards in rich layers as Morley begins to suspect the existence of an author 200 years in the future who may also have a hand in writing this grand story. Like the enchantments of the night, it takes us to quite unexpected places and is alive with hints that, although they might not play out as we thought, are no less delicious for it.

There was also something of the magical in how I came to read the book. Having learned of Strange Attractor Press and its biography of Austin Osman Spare, Somnium also caught my eye as I was perusing their website. But I thought nothing more of it until a few weeks later I had just finished Israel Regardie’s essay ‘The Art And Meaning Of Magic’ and the following day, quite out of the blue, I was asked to interview Steve Moore regarding his new book. Regardie’s essay, when describing the Sephiroth of The Tree of Life, primarily deals with Yesod, the sphere of the moon. So fresh in my mind were the traditional attributes of that heavenly body – its colours purple and silver, its jewels pearl and moonstone, its number being nine, and so much more; traits Moore makes wonderful use of throughout the book. Though one need not be familiar with these to appreciate its splendour.

I also attended Steve’s first ever public reading a few days after that. Wondering which section he would read from, and knowing the excerpt below, I almost blushed for an unsuspecting audience to hear such words. But he began, decked out in his black satin Oriental jacket, at the beginning. And I smiled, musing on all those thus-enchanted had yet to experience.

Where did Somnium come from? The book often speaks of real life and the world of dreams being one and the same. For many years you’ve kept a dream journal and you’ve mentioned that you worked on the book at night, did any of Somnium actually come directly from dreams or were they more of a springboard?

Steve Moore: Hmm, starting with the easy stuff, huh?! Where to start? As anyone will know who’s read or heard Unearthing, Alan Moore’s biography of me, my relationship with the moon-goddess Selene goes back to 1976 and a ritual request for guidance, after I’d acquired a Chinese magic sword. As I’d been thinking in a Chinese context, the result was completely unexpected, but after that I started researching Selene’s mythology (and have now almost completed a non-fiction book on the subject, which should be finished early next year). At the same time, certain lunar elements started creeping into my comic-strip work, and the story of the goddess Selene and her sleeping mortal lover, Endymion, became not only an archetype that seemed to be taking over my life but also something of an artistic obsession.

My first attempt at handling the subject was actually the blank verse play, written sometime in the early 1980s, which I ended up inserting into the final version of Somnium, and the hero of the book, Kit Morley, actually refers to it as a work he’d written in his youth. Then sometime in the early 1990s (I think), Alan and I talked about doing a graphic novel based on the myth set in Victorian times, just called Endymion. I wrote the script, and Alan was actually going to draw it, but nothing ever came of it. Come 2001, I decided to combine a certain amount of magical practice centred on Selene with writing the novel that became Somnium. The two things were pretty much inseparable, but that’s often the way Alan and I do Moon And Serpent things … the magic and the art combine in a creative process and the ‘working’ ends up as a ‘work’, in this case Somnium. It was a completely fresh start, though there really isn’t anything of Endymion that’s ended up in Somnium, except perhaps a similarity of mood. At the time my emotional life wasn’t in the most positive state, so Somnium became a way of working through that and an act of self-transformation, as well as an offering to Selene.

Alan’s suggested in the afterword that there’s some sort of connection between the Diana Regina character and Diana Rigg, and it’s true that, like an awful lot of guys who were teenagers in the 1960s, I did kinda have the hots for Diana Rigg. And she does linger in the memory (The Avengers remaining one of my favourite TV series to this day; in fact I’ve just finished watching the complete series all over again). But I don’t think there was any conscious connection when I was writing the book. Diana Regina was simply ‘Queen Diana’, and so a suitable title for my lead character, and I really didn’t visualise her as looking like Diana Rigg. Far be it from me to claim anything was ‘mere coincidence’, but I suspect this was more of a subconscious mind-trick than anything else.

There were two reasons I was working on the book at night. One was that I was doing commercial comic-strip work during the day; the other was that it seemed more appropriate to make it a nocturnal activity, considering the subject matter. And, besides, it was purely a spare-time activity that I worked on when I felt like it, without any particular intention to publish, so it took three or four years to finish, with numerous revisions. The word ‘Somnium’, of course, is Latin for ‘dream’, or ‘sleep’ in general, but it also seemed to have something of the name of a fantastic city about it, so it was an obvious choice. I’d started keeping a dream journal several years before the 1976 ritual and, apart from a few years in the early 80s when I was too stoned, I’ve kept it up ever since. Generally I’d say that the dreams were more of a springboard, though for years I’ve dreamed of gigantic buildings with fantastic architecture, rather like the beautiful palace that John Coulthart has pictured on the cover of the book, though usually decorated with huge art nouveau statues as well, and this is so common I just refer to it in my journal as ‘Somniac architecture’. As far as I remember, there’s only one actual quoted dream from my journal appearing in Somnium, which comes in the letter from the modern author, ‘S’. It’s on page 203, and it’s ‘I was walking past The Bull with Alan, talking about Somnium, and I told him I’d decided to include a sequence where he and I were walking past The Bull, talking about Somnium, and including a sequence where he and I (etc., ad infinitum).’ That’s absolutely genuine, and was obviously so relevant to the book, with its layers of reality and dream, that I just had to include it.

How does it feel now the book is completed and published?

SM: Well, obviously it feels good, and I’m delighted at the reaction so far. I’d completely failed to sell it to the commercial market soon after it was finished, which didn’t surprise me in the slightest, considering the nature of the book, so I’d begun to think it was going to be one of those things I just showed to friends. Fortunately, one of those friends was Val Stevenson at Nth Position, who suddenly announced a few months ago that she was starting publishing ebooks and wanted to do Somnium. Alan then immediately said that he wanted to write an afterword, and also suggested that we do a limited edition hardback that we could both sign. So at that point I spoke to Mark Pilkington at Strange Attractor Press, who did all the production work and distribution on the hardback, and suddenly we were in print. I was pretty surprised, but I’ve come to realise that these things happen when they’re supposed to happen, and sometimes I feel that everything that Alan and I do with regard to Moon And Serpent related stuff is just part of some bigger process. You know, we ‘delegate upwards’ to the gods, and they sort things out when the time’s right. It makes things a lot less fraught than trying to do everything yourself!

Have you become aware of any “unusual occult feedback”, like Alan Moore suggested to you might occur when one introduces “a loop of self-reference”?

SM: No sooner was the book out than Luminous Books decided to hold a ‘Moon evening’, so I ended up doing my first ever public reading there. It’s very tempting to see some entity amusing themselves with things like that. More specifically, though, Mark tells me that someone reading the book had tweeted that it was ‘affecting their dreams’. Isn’t that just perfect? And while I was actually sitting here writing this answer, a cousin emailed me a whole bunch of very artistic moon photos. This sort of thing happens to me all the time…

Speaking of Alan Moore, how has Unearthing affected your life?

SM: It’s a bit hard to say. At least no one’s cried ‘Burn him!’ (Yet.) I tend to look on the whole thing with bewildered surprise… as I’ve said elsewhere, I think everyone tends to define ‘normal behaviour’ by what they do themselves, so when someone thinks you’re interesting enough to write about, you tend to think, ‘Why?’ And when it then becomes an audio-recording, a soon-to-be-published photo-illustrated book, and who knows what else in future, you can see why I’m baffled! On a day-to-day basis, I can’t say it’s really affected my life so far. What it’s probably done, though, is to make me a bit more confident. After all, Alan’s done such a thorough exposure of me I’ve really got nothing left to hide. Everyone can see I’m a lunatic, so I might as well just get on with it!

Alan and I tend to see all this as an ongoing process, somehow. Somnium, the non-fiction Selene book, Unearthing, Alan’s forthcoming novel Jerusalem, The Bumper Book Of Magic… they all seem to be part of some sort of vague, barely-defined Moon And Serpent project to provide an alternative view to simple materialistic reality. We’re willing partners in the project, but control’s been delegated upwards. It all kicked off with that ritual in October 1976, but where it’s going from here… well, I guess the gods know!

If you care to, tell me about the Chinese coin sword and your first attempt at magic. I find it interesting that the sword contained 108 coins, which adds up to nine. How much association did you have with the Moon before this?

SM: In the 1970s I was really into traditional Chinese culture, an interest that sprang from my fascination with historical Chinese sword-fighting movies and later led to work on the I Ching. One day in 1976 I picked up a book with a picture of a Chinese coin sword in it. They were used as talismans to ward off evil spirits, which were thought to be yin. So the coin sword is all yang: the coins bear the name of the emperor, the Son of (yang) Heaven, it’s bound with yang red thread, the sword is straight and sharp, which are yang characteristics, and so on. 108 is originally a Buddhist lucky number, but became popular in China and, as you say, 108 adds to nine, which is the number of the moon in western occult tradition (you won’t be surprised to hear that I now have nine coin swords, though actually I’ve only just realised this). So, having seen the picture I thought ‘I want one of them!’ and about six weeks later I was passing an antique shop in Blackheath, and there was one hanging in the window. Needless to say, it was priced at £9.00… but the woman in the shop let me have it for £8.50 because I could tell her what it was!

So, having acquired a ‘magic sword’ I decided I was going to do a ritual with it. I didn’t have any practical experience before but I’d been interested in occultism and I had a few books, so I checked things out and wrote myself a little ritual. It was all done without drugs or anything else to get me into a trance state. I made myself a little circle, with the trigrams of the I Ching round it, and so forth, and I went through with the whole thing and asked any gods, spirits or (Taoist) immortals that might be listening for some sort of guidance, and for a confirmatory dream. I was so into China at the time that I expected that, in the unlikely event of my getting a result, it would be something with an oriental flavour, but I woke up at 4:00 in the morning to hear a voice say ‘Endymion’, which I later found to be the name of Selene’s lover. So that prompted many years of research and a total immersion in Greek myth and religion, etc. And my life’s pretty much been ‘guided’ by a lunar obsession ever since.

What happened before that?

SM: Before that? Well, I was born at the full moon atop a crescent-shaped hill, the main mineral found here being selenite, and I have a slightly rough-edged crescent birthmark on my left forearm … so I was obviously destined to be either a werewolf or a lunatic. Fortunately there’s been no sign of fur or ripping out people’s throats so far. It was really only the ritual that made me fully aware of this lunar disposition, but since then the synchronicities have just kept on coming. I guess someone up there in the moon likes their little jokes.

This is only a vague notion but I bring it up because it came to mind on more than one occasion and also gets a mention in Unearthing – the novel, The Turn Of The Screw. It’s been years since I’ve read it but something of that unnamed menace/danger seems to me present in Somnium. Obviously I don’t want to give away too much, but was Henry James’ novel in your mind at all? Does that book mean anything to you? What are your favourite novels?

SM: Obviously it’s very flattering to have Somnium and The Turn Of The Screw mentioned together, but I have to confess I’ve never read Henry James’ novel, despite the fact that Alan mentioned it in Unearthing. So I’m afraid it doesn’t really mean anything to me.

What was Kit Morley reading in 1803? What are your favourite novels?

SM: In 1803, as mentioned in the book, Kit Morley would certainly have been reading William Beckford’s wonderful Gothic/Oriental fantasy, Vathek, which happens to be one of my favourite books as well. And I suspect he’d have been reading other Gothic novels of the time, such as Matthew Lewis’ The Monk, and possibly some of the German Romantics like Goethe. As for my favourite novels… hmm. Probably at least half of my reading is non-fiction, anyway, but I’ve read a lot of science fiction in the past, particularly people like Jack Vance and Leigh Brackett. But I also read mediaeval romances, like Malory, the Decadents, like Gautier, Wilde and Huysmans, and Romantics like E T A Hoffmann. Probably my favourite author of all is Clark Ashton Smith, the American Weird Tales author, because, like the Decadents, I just love his language but, of course, he only ever wrote short stories. What I don’t read much of, I confess, is contemporary fiction but then I guess you’ve only got to read Somnium to realise that.

With so many different stylistic sections of Somnium, do you have any particular favourites or any that were most pleasing or difficult to write? The poetic language of Diana Regina and her world is especially lovely, did that come easily?

SM: Writing prose fiction the way I do is always pretty hard work because I pay so much attention to word-choice and to rhythm; all the time I was writing I was reading it back aloud to make sure it flowed properly. I can’t say that anything was particularly difficult, though I did have to be careful with the Elizabethan Diana Regina material not to make it overly sentimental. If I had to pick out one ‘favourite’ section of the book, it would probably be the inserted story ‘This Dull World, and the Other’, which you’re running an extract from. It just has more humour and elegance than some of the other material, and it really allowed me to let my peculiar imagination run wild.

Interview continues after cover art

I gather the ‘Decadent’ short story was something you had already written and then imported into Somnium, coming from the future back to 1803 from an author known only as ‘S’, clearly yourself. I was particularly impressed with how well this worked and its lightness of touch, the presence of a ‘future author’ only occasionally hinted at in Morley’s dreams and their recollection, never too much. Were you tempted to write more of yourself into the novel?

SM: Actually, the only section that was pre-written and imported into the book was the Endymion play. I started off with a draft of the 1803 Kit Morley section, which was originally written as a series of letters, rather than a journal, and then followed that with the Elizabethan Diana Regina material, though both of these went through frequent, hefty revisions, especially as I was fitting the book together. After that came the Decadent ‘Dull World’ and finally the Mediaeval ‘Lady Luna’. Then probably the Kit Morley section got the most revision of all, as I attempted to fit all the other material into it. But, no, I wasn’t really tempted to write more of myself into the novel. I think at the time my thought was more, ‘Can I actually get away with this idea?’ so I tended to keep my presence as minimal as possible.

Let’s talk about the excerpt. What was the inspiration for this short story?

SM: When I started writing the book I was nearing the end of my ‘Obsession With The Elizabethan Period’ phase, and by the time I got to the ‘Dull World’ story I was into a ‘Let’s try reading everything I can find by or about the Decadents’ phase, so I wanted to write something in that style. Probably a more direct inspiration for the story was that, now I’m becoming old and decayed myself, I find I tend to nod off while reading (especially after a good lunch) and fall into a sort of ‘daylight dream’. So I’ll be reading a really ordinary passage about, say, ladies at a tea party, and then it’ll seem to say something like ‘and then the fourth brother hacked them to death with an axe’, and I’ll jerk awake and think ‘What was all that about?’ So that’s where the whole idea of the book that hides in other books came from, and after that I just let my imagination go.

I was very impressed with your article on the Decadents in the third issue of Dodgem Logic. Any favourite personalities, works or anecdotes from that era?

SM: Thanks for the kind words. I just found the 1890s fascinating, especially for its resonances with the 1960s – new styles of art, writing and music, drugs, dandyism and a disregard for convention, a feeling of renaissance and a lot of that applies to the Elizabethan period too. And, naturally, people like Oscar Wilde, Théophile Gautier, Lafcadio Hearn and the like just wrote so beautifully, with a full command of the language and a vocabulary to die for. And, of course, they did tend to ‘upset the bourgeoisie’ quite a lot, which is always a good thing. Of the poets, there was John Barlas, who took a dislike to the Houses of Parliament and shot [at the building] with a pistol; or poor Edward Dowson, who laid his heart at the feet of an 11-year-old girl and then waited until she was legal, at which point she promptly married a tailor. Absinthe and tuberculosis carried him off soon afterwards. And there was Sarah Bernhardt on the stage, and Alphonse Mucha producing that wonderfully lush art nouveau illustration. How could I resist paying a literary tribute to guys like that?

How is The Moon And Serpent Bumper Book Of Magic coming along? Any interesting recent findings? When you say it’s about half-finished, how long does that portend the finished book to be?

SM: Well, it’s still coming along, but very slowly … though Alan and I did some more work on it a few days ago. It’s been held up recently because Alan’s been busy trying to get Jerusalem finished and working on other projects, and, of course, I’ve been seeing Somnium through the press. It doesn’t help either that he lives in Northampton and I in London, but we’re both aware that we need to get down to serious work on it again. It’ll be 320 pages long … not for any particularly magical reason, but just because it seems like the right sort of length to cover everything, and books are printed in signatures of 32 pages anyway … and we’ve got about half of that written. We’re currently stumbling through a series of pieces on ‘magical landscapes’ that can be visited in trance or by ritual, each of which is being compressed into a single page, but once that’s out of the way we can get back into some of the stuff that isn’t quite so labour-intensive, so then it should speed up a bit more.

What else are you working on at the moment?

SM: I’m otherwise semi-retired, so I’m not doing any commercial work at the moment. As I mentioned, I’m finishing off my non-fiction book on the mythology of Selene, which is more or less complete but needs a fair amount of revision. And I’m very slowly working on a humorous fantasy novel called Scrollwork, which may see the light of day eventually. That’s completely different to Somnium, being set in a total fantasy world and featuring a lead-character who’s an idiot, though it still centres on some of my usual obsessions, like the fluid nature of reality. And sometimes I just write short fantasy stories to entertain myself and my friends. When you’ve been writing all your life, it’s very hard to stop …

Where would be a good place for a beginner to start with the I Ching? Any reliable books?

SM: I’ve been a bit out of touch with the I Ching in recent years, mainly because a terminally-ill relative took up a lot of my time. Although it has something of a Confucian bias in its interpretations, I’ve always used and referred to the Richard Wilhelm translation, and I haven’t so far found one I prefer. A good compendium of material on The Book Of Changes, if a bit expensive, is my old friend Edward Hacker’s I Ching Handbook. A really good (and cheap) historical introduction by another friend is William de Fancourt’s Warp And Weft: In Search Of The I Ching. My own book, The Trigrams Of Han, is mainly about the I Ching’s structure, and really wouldn’t be a beginner’s book… if you can still find it.

I found your essay in Strange Attractor Journal 2 fascinating, with the combination of artistry, rivalry, and (perhaps well-meaning in some cases) misplaced and incomplete information that went into early Western interpretations. Any more to say on this?

SM: You’re right about the peculiarity of Western interpretations of the I Ching. One thing I’ve always found fascinating is the way it’s presented in the West as a book of instruction as to the correct way to act in certain situations, rather than one that could be used to make predictions; whereas in China it was both. But, of course, a predictive use can suggest that the universe is deterministic and predestined, which doesn’t fit with either Christian or Western rationalistic ideas of free will, so predictive divination becomes the ‘elephant in the room’ that no one talks about. The way my life’s gone, I tend to find an insistence on ‘free will’ quite amusing…

You wonderfully tell of the music of the Moon through both your 19th Century character, Kit Morley, and his 16th Century creation, Endimion Lee – pavanes, “lute-notes”, Phrygian modulation… These are of their time but the Moon herself is also both eternal and rapidly changing in her 28-day cycle. What do you yourself think the music of the Moon sounds like?

SM: I actually wrote a little story called ‘The Music of the Moon’, with a Chinese setting, which suggested that it was so rarefied that it could hardly be heard at all in the world of the living. I tend to think of it as something cool and crystalline and distant, probably played on a solo instrument, like the lute, harpsichord or the Chinese zheng, but very complex… perhaps something like a slow Scarlatti harpsichord sonata, but played a very long way off, at the edge of hearing.

And my standard last interview question, seen a bit differently in this light, is always – Say you’ve stolen a space shuttle and are flying it directly into the sun, for whatever reason, what would the soundtrack be?

SM: If I’m flying directly into the sun … the obvious answer would have to be The Misunderstood’s 1966 single, ‘I Can Take you To The Sun’, which was actually a track I dearly loved at the time. But music I’d want to have playing as I cast myself into a fiery inferno? Not really sure … my musical tastes tend to vary so much, having run through English R&B and psychedelia to West Coast rock, to jazz, classical, World, and all kinds of stuff, even Oriental. I’m sure there’s more beautiful music to die to, but if I could only take one album with me it’d probably be the second one by the Yardbirds, known these days as Roger The Engineer. Mono version, of course. Always very fond of Jeff Beck. And in case you’re wondering, the answers to this interview were entirely written to Paco Peña’s flamenco guitar.

Somnium is available via Strange Attractor Press now

An Extract From Somnium By Steve Moore

And then she told him he should stoke the fire and strip down to the waist, so she could paint Egyptian hieroglyphics foully on his chest that came from ancient Karnak, and several words in Greek, that evil reeked, and certain Hebrew letters too, that seemed to him the worse, for they were angel-script and spoke of naught but demons. And when she had, she stripped herself quite naked, all unblushing, and told him he should paint the same on her; and how he trembled as he brushed those burning words across her soft young breasts. Then standing hand in hand, they called upon the name, Opusculum Mercurialis. Or he called it by its name, at least, and she sang noxious incantations hardly heard since golden gloried Rome fell from its might and crumpled like a craven to the conquering Christian horde.

Ten minutes passed and nothing happened, yet they did continue just the same; then Théophile’s attention wandered somewhat. For the beauteous Eugénie was swaying nakedly before him as she sang, and once again he saw her young bared breasts, and all the rest of her which, not exactly flaunted, was not exactly covered up. And sin began to heat up Théophile’s imagination then; and from the corner of his eye he saw a vagrant greenness first and, almost shyly, that quite improbable book slipped across the gulf of time and space from its strange, uncertain world and nestled snugly in his hand.

And Théophile, who rather feared the holding of it would burn his flesh away in agonies quite transcendent, then remembered all he’d dreamed, and tempting promises of Hermes, and six bright eyes that sparkled ‘yes’, and all the sin of his desire, and how it did allure… and handed then the book forthwith to eager Eugénie.

She clutched it close and made it fast with certain noxious recitations learned in Smyrna, that orient city scented all with myrrh and unbecoming foulness, and painted symbols on its back and front that would not let it get away, back to its own and other world, no matter how it sorely wished to. Then, without the merest thought of covering up her nudity, she took a pace or two toward the fireplace, opened the little, innocent-looking book and began to read aloud such evil things he thought he would expire.

How Remus had been sodomised to death by Romulus while giant birds of prey pecked out his bleeding lungs until he had no breath to scream. How Helen, cursed by all the Gods at birth because her beauty was too great, aged never more than up to twelve until her dying day, and always was a child in bed who did not understand at all the things that men desired, and did; and ever wished that she could die, and didn’t. How handsome Antinous, because he was too loved, was cut in tiny pieces by old Hadrian his lover, fried with onions, most sacred plant of Egypt, and eaten by the emperor, all his blood-sauce drunk as well, and bones boiled up for soup, till nothing did remain. And how Pyriphlegethon, the fiery river, rises up from hell each night, to burn the innocent as they pray to all their innocent Gods, who quite refuse to save them. And of the sex-life of the dead, decayed, which was more lewd than all the whores of Paris could imagine, put together. Of living stones that turned to fiery lions, all-hungry in the all-too evil night; of gates to other worlds where everything was worms, and maggots and corruption, stinks and blight. Of oceans turned to crimson by the blood of sacrifice, and all for nothing but the charm of coloured death. Of sepulchres that glow on moonless nights and spiders twice as large as Athens ever was. And hordes of giant rats that ate the sun itself when it settled on the horizon. So many things the slim, unwholesome volume seemed then to contain, he knew they would not all fit in, and somehow it was more than first it did appear… so many times more over.

And Eugénie, she stood there naked by the fire, and read with such a lickerish look upon her lovely face, that Théophile cried: ‘hold, enough!’ and asked her to explain. What meant this awful book, and why had she desired to have it?

Then Eugénie glanced up, and saw the look of innocent, tremulous pain upon his face and, if not for long, the spell the book had wove on her was, for the moment, broken. She put it on a table (it did not disappear), invited him to sit down in a chair nearby, sat down herself, and took his hands in hers, so small.

‘Dear Théophile,’ she said, a phrasing he thought rather pleasing, naked as she was, ‘I’ve always known, in ways that you perhaps have not, the difference between what’s real and what we think is true. For what we think is true is mostly what we have been told, and not what we have seen with our own eyes. And what we have been told about the ancient world, is lies, and lies, and lies. The Christians, when they took the world, they made it over as they wished, and so they made it plain and dull and boring, denied all mystery and all sensual entertainment, declared that incest, sodomy and bestiality, necrophilia too, and both the ways of Onan, all those things that make life sweet and full of interest and variety, were foul and horrid sin. And banished Gods and fauns and nymphs, lamiæ and sphinxes, chimeræ and wyverns, Mormo, Baubo, Gorgons, gryphons, gigantic worms that fed on shuddered maidens’ flesh till they were done away with quite by heroes armed with adamantine blades of orichalch, though always then there came another, hungrier than before, and larger too… and more, they did away with sorceresses, with their violet eyes and lovely breasts, and red hair swirling round their dainty ankles, who thought it fine to fornicate with fauns and pans beneath a golden gibbous Moon, and make sweet music with their sighs and gasps and cries and moans; and so they did away with spells and wonder too; and tombs that housed the living dead, and parricides that slept then with their mothers and charred their hands and feet besides, and drugs that show a glimpse of heaven and blind us then for ever more, and women with the heads of crows and feet of mice, and ladders quite of diamonds leading to the very stars themselves, that glitter in the night of time, and tell eternal hours of pain in hell. So hardly surprising was it then that men were bored, and prayed unto the Christian God to save them from this dullness. And he, of course, so full of goodness, leaves them as they are. Do you wonder then that men do open up a vein and die, a-weltering in red blood that’s all their own? The only surprise to me is that they do not do it sooner and more often.

‘No, Théophile, I will not live in such a world and nor, I hope, will you. I want to live in Hermes’ world, which, though it is not here with us, was never quite destroyed. It hid, and saved itself for those who sought it, such as me, who thought it not a sin to live a sensual life, and think such thoughts… such pagan, lovely and, by Christian standards, evil thoughts as I do. I know you think me sweet, my dear, but all the line Sylvaire have been voluptuaries since the pagan Franks they first arrived, and took their joys promiscuous. And if I cannot gratify my body and my mind, destroy my foes like angry Mars and love my friends like soft and lovely Venus, all perfumed, and think then all the thoughts that can be thought within the world at large without a moral judgement just the same as Hermes-Mercury, trim the fatheads like young smirking Glycon, naughtier far than man and snake together, storm like triple Hecate when she magic-makes the world as she desires, and sleeps with all her dogs so dark, or copulate like Thracian Bendis of the leather dildo, then what’s the point of living, and what’s the price of body and of soul?