Alma Warren is a successful, internationally-acclaimed artist who nevertheless continues to lead a low-key life in her local Northampton, where she is regarded as a loveable if slightly dangerous eccentric. She is also a fairly obvious stand-in for Jerusalem author Alan Moore – to the extent where it’s impossible to imagine the hulking, curtain-haired, dope-smoking old woman, who is a pivotal character in the novel in question, without a huge bushy beard to boot. Jerusalem begins with a vivid dream that Alma experiences as a child, setting up the book’s two parallel strands; a sometimes nostalgic but always unsentimental portrait of life in Northampton’s Boroughs district throughout the ages, and an equally detailed rendering of the vast supernatural universe of significance, symbolism and destiny that lies behind it.

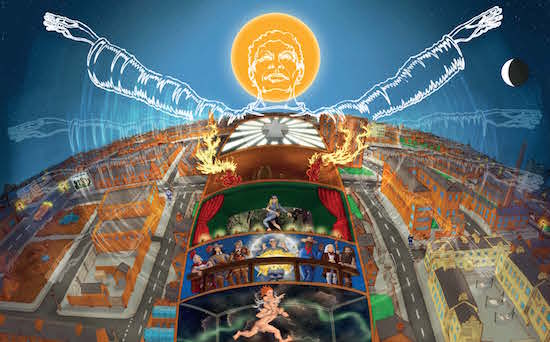

This is a working-class cosmology, in which gods and angels are not kings and lords but working men: building and crafting the universe, playing billiards and generally getting their hands dirty. They’re also not above settling matters with a cosmic punch-up if it comes to it, and it does, all because of the near-death experience as a three-year-old of Alma’s younger brother Michael. When another brush with mortality as an adult causes Michael to recall some of what happened during the ten minutes as a child when he was technically dead, Alma is inspired to create a series of 35 paintings which mirror the chapters of the book and are exhibited at its conclusion.

Michael’s adventures in the afterlife, in which he’s aided by a clutch of ghostly Bash Street Kids known as the Dead Dead Gang, take up the entire 400-page middle section of Jerusalem. Around this, books one and three span hundreds of years and dozens of characters in the Boroughs and occasionally Lambeth (which in Jerusalem’s dream-logic are almost the same place, or at least adjacent). We meet poor mad Ernest Vernall, whose doors of perception are wrenched open so wide he’s condemned to Bedlam in the 1860s; his equally afflicted / visionary offspring Snowy and Thursa; and all of their various descendants- mostly generations of strong, complexly drawn women- right down to Alma and Michael Warren. Outside of the Vernalls and the Warrens, we also meet Marla, a modern-day teenage sex worker obsessed with Princess Di and Jack the Ripper, whose real life seems almost permanently delayed; her equally marooned contemporary, the damaged poet Benedict Perrit; a medieval monk with a sacred burden; Henry George, a black American and freed slave who comes to live in Northampton at the very beginning of the twentieth century; and many more individuals, all with their own interwoven stories, and all of them in some way symbolic of the resilience and potential of ordinary people and their environment, and the way that potential is so often crushed by circumstances and the impersonal forces of history, but can never be lost for good.

Jerusalem is essentially an epic, multi-generational saga of ordinary, working class folk that just happens to have a high preponderance of ghosts, angels and devils among its cast. It is also based on a true story: Moore’s own family history, from his great-great grandfather’s visionary apocalypse to his brother Michael nearly choking to death on a cough sweet as a child. A cosmic exploration of the nature of time, existence, the afterlife and the multi-faceted universe we live in, it’s also a conscious piece of visionary myth-making centred on the Boroughs, the poor, working class district of Northampton where Moore grew up. It’s an attempt to record its characters and legends, its places, its past, present and disassembled future, and to somehow save and redeem it all through art. In so doing it takes on the pernicious and callous materialism of Isaac Newton and Adam Smith, as well as The Destructor, a 1930s incinerator that still exists on a higher plane and is obliterating everything meaningful in the Boroughs and beyond, simply through what it stands for: "This is where we send our shit, the things that we no longer have a use for. This means you."

Unfortunately, while Jerusalem has generally been well-received, there’s a snobbish, patronising undertone to some of the reviews, where certain critics appear to have taken obscure offence at being presented with an ambitious, 1200-page literary work written by an eccentric upstart who is a) a writer of comic books and b) working class. As a result, their reviews have an implied message of: stick to making comics, son, and leave the proper books to educated, middle-class writers who were born to it, and know what they’re doing.

"Obviously literature was still seen as the sole preserve of the elite, which is just one of the reasons why John Bunyan’s writings, crystal-clear allegories conveyed in common speech, were so incendiary in their day… these weren’t the rakish, courtly witticisms or the fawning tributes of contemporaries such as Rochester or Dryden. These were written by a member of that new and dangerous breed, the literate commoner. They were composed by someone who insisted that plain English was a holy tongue, a language with which to express the sacred. Of course, they’d banged Bunyan up in Bedford nick for getting on a dozen years, while art and literature are still most usually a product of the middle class, of a Rochester mind-set that sees earnestness as simply gauche and visionary passion as anathema. William Blake would follow Bunyan and, closer to home, John Clare, but both of these had spent their days impoverished, marginalised as lunatics, committed to asylums or plagued by sedition hearings. All of them are heirs to Wycliffe, part of a great insurrectionary tradition, of a burning stream of words, of an apocalyptic narrative that speaks the language of the poor."

-Alan Moore, Jerusalem.

Born into a working class Northampton family in the early 1950s, Alan Moore was expelled from school at the age of sixteen for selling LSD. For good measure, his headmaster wrote to all the other schools and colleges in the area advising them not to accept this morally degenerate troublemaker as a student, or words to that effect. Despite Moore’s evident intelligence and creativity, all options at conventionally bettering himself and getting on in life had been taken away from him. The doors to the academy were closed, and Moore found himself working in a sheep-skinning yard and cleaning toilets to make ends meet. A lifetime of shit jobs, low pay and drudgery stretched ahead of the would-be writer /artist, and working in comics seemed the only viable way out.

In 1970s Britain, comic books didn’t enjoy even the grudging modicum of respect they attract today. Graphic novels were unknown, and while black and white reprints of Spider-man and The Hulk shared newsagents’ shelves with Roy of the Rovers, the Beano and Whizzer and Chips, the idea of writing for Marvel or DC over in the states was nearly as remote for an unqualified Northampton lad as being taken seriously as a budding novelist by the big London publishing houses. UK comics on the other hand were strictly aimed at little kids, and writing or drawing for them was considered hackwork where the only minimum standard was the ability to stick to the formula while working fast and cheap. While a slightly older and London-based working-class writer like Michael Moorcock could earn decent money and build up a literary portfolio knocking out science fiction stories for the pulps, even that market was dwindling by the time Moore came on the scene. Writing comics was really the only option, yet even this was to some degree a closed shop: Moore’s contemporary Bryan Talbot has recalled the suspicion and mistrust with which the regular comics freelancers regarded a young hippy kid who actually wanted to do good, creative work in the medium. This was a line of business where earning a living meant churning work out on a production line basis to the bare minimum standard; the old guard didn’t have the luxury of being able to spend time crafting art.

Moore’s salvation came in the form of a mini-renaissance in British comics, triggered by the appearance of a science fiction themed comic aimed at slightly older kids, 2000AD, in 1977, and Marvel UK’s decision to start commissioning and publishing home-grown material, also aimed at slightly older readers. Moore sold some back-up strips to Marvel’s Dr Who Weekly, and then was given the chance to work on a reboot of the company’s perennially misguided but oddly likeable Captain Britain character. Meanwhile he was selling one-off, 3-5 page strips to 2000AD and eventually created Halo Jones and DR & Quinch for the comic. Most significantly, in 1982 ex-Marvel UK editor Dez Skinn launched a short-lived intelligent comics anthology called Warrior, in which Moore’s Marvelman and V for Vendetta soon proved the most popular strips. Moore was now the darling of the British fan community and as a result was soon spotted by the voracious eye of the ever-hungry American comics industry. The rest is bittersweet history, leaving Moore- a self-described "experimental artist" who is also a magician, film maker, illustrator, musician, poet, performer, essayist and journalist- fated to be remembered forever as the man who reinvented comics / the superhero and then got famously grumpy about the whole business and disowned the lot.

But perhaps not. Actually, I think there’s every chance that for future generations Moore will be remembered primarily as the author of Jerusalem; as a genuine working-class genius and world-class writer who just happened to get his start in comics because there were no other avenues open to him. Of course, at times Jerusalem recalls elements of Moore’s previous work. He’s explored the nature of time, drawing on the theories of Einstein and Ouspensky, from Watchmen onwards. Promethea gave us a detailed tour of a metaphysical universe mapped onto the Kabbalah, while in The league of Extraordinary Gentlemen Moore borrowed the Blazing World from Margaret Cavendish and made it into a crossroads of fictional universes that has much in common with Jerusalem’s Mansoul (itself borrowed from John Bunyan, and overlaying Northampton while the Blazing World is accessed from above the North Pole). There are even faint echoes of Moore’s proletarian comedy The Bojeffries Saga, leading one to wonder if some of that strip’s weird grotesques were loosely inspired by the same real-life Northampton folk Moore more closely draws on here. But even Moore’s greatest comic scripts now seem like rough sketches for the full flowering of the mammoth, ten-years in the making Jerusalem. This may be not only Moore’s masterpiece, but one of the most significant serious novels of the 21st Century so far.

It’s a long book because it has to be. Moore takes a maximalist approach; he wants to include everything. There are perhaps moments when it feels like every scrap of unlikely history and notable figure relating to Northampton has been shoehorned in, but these are never less than interesting and intriguing (and if you’re not actually from Northampton, back issues of Moore’s locally focussed underground mag Dodgem Logic may help to fill in some of the background). All of the digressions are relevant, as are all of the scenes repeated from different characters’ points of view, because this is one of the book’s central messages: everything is relevant. Everyone’s point of view is relevant, and everyone’s history is relevant, and every moment is sacred and eternal. Actually, Jerusalem could easily have been longer; several major plot points are resolved only by implication, and what eventually happens is clearly suggested but never spelt out. For all its size, Jerusalem is pretty economical, relying on the reader’s own imagination and reasoning to fill in the gaps.

For those still put off by the sheer stoutness of Jerusalem the book is available in a slipcase edition of three very manageable 400-page paperbacks, albeit with painfully small print, and isn’t on the whole a difficult read. The exception to this statement is the notorious 45-page chapter written from the perspective of Lucia Joyce, incarcerated in a Northampton asylum following a breakdown, which is written entirely in the style of Finnegan’s Wake. Persevere however and this chapter yields up some of the novel’s most rewarding moments. Moore has always been adept at creating multi-layered composite words and at having fun with puns and allusions, and the wordplay in this chapter is frequently both insightful and hilarious. Plus it conceals the book’s most outrageous sex scenes.

Jerusalem is also psychedelically informed without being a ‘druggy’ book. Moore’s avatar, Alma Warren, may be shown to smoke heroic amounts of weed fairly continuously, but otherwise drug use is portrayed as just another mundane facet of contemporary life. Alcohol, crack, smack, crystal meth and even salvia divinorum are presented as potentially ruinous crutches that those poor and bruised by life are forced to fall back on. But elsewhere a passing character is described approvingly as having a psilocybin mushroom and the legend ‘Magic’ tattooed on one arm and ‘fuck off’ on the other, which Alma Warren thinks are both "worthy creeds to live by". Certainly, anyone who has enjoyed the beneficial properties of mushrooms or LSD will recognise some of the visionary ideas and descriptions in Jerusalem. But if those substances open a crack in the cosmos to give one a glimpse of the divine, then Jerusalem opens that crack wider and shows us the full complexity of the world in a grain of sand, and a heaven in a wild flower.

Even the metaphysical premise of Jerusalem favours the poor, huddled masses rather than the "great leaders" of conventional history. This is the theory of Eternalism: the idea that everything that happens has already happened and is always happening, and that our sense of time is just a necessary illusion that enables us to function within a simultaneous universe. This means that everything that occurs in our lives is already there, and our consciousness just moves along it from moment to moment, like the light of a projector striking each frame of a film, or indeed our eye moving across a comic book from one panel to the next. When we die, our consciousness simply returns to the beginning and repeats the process, although with no memory of having gone through it before. In Jerusalem Moore suggests that this eternal return is optional; we can also "go upstairs" to Mansoul, a kind of imperfect afterlife, a fallible heaven-cum-dreamworld. There is also the "ghost seam," inhabited by "rough sleepers": departed spirits who feel that they’re not worthy to go upstairs but instead remain to haunt the sites of their previous lives, existing in a colourless, intangible realm overlaid on our own and able to move freely through time, though seemingly limited in how far they can travel in space.

Eternalism implies predestination, and so denies the existence of free will. But as an archangel says to one of the recently dead characters in Jerusalem, "did you miss it?" Free will, like time, appears to be just a necessary illusion, apparent on a personal level but growing less so the more you look at the fate of whole communities, countries or planets. Of course, it is the poor who are most often blamed for their actions when in fact circumstances and social forces conspire to rob them of any real choice. Jerusalem then is both a highly moral work and deeply non-judgemental: we largely have no choice in our actions, we are not being continually judged from above, there is no such thing as sin and no such thing as virtue. But at the same time we should be mindful of trying to live each moment in a way that we can live with forever, because if Moore is right, we may have to.

Drawing on Blake and Bunyan, Moore has created a fully-realised working-class mythology that is utterly contemporary and much-needed. In an era when the working classes are portrayed as hopeless victims or demonised as thugs and idiots, while all the while being urged on to greater extremes of racism and xenophobia by the popular media, Jerusalem rejects the portrayal of limited horizons and the glamorisation of poverty that Moore sees in TV shows like Shameless in favour of a work that grants dignity and profundity to life at the bottom of the economic shitheap, while also urging us to raise our sights above our immediate circumstances. We are our own final judges, our own imparters of meaning, and in amongst the dark satanic mills of our ordinary oppressed existences, we are all already living in the shining, eternal city of Jerusalem. Nothing ever ends.