All photographs by Paul Allitt, courtesy Wysing Art Centre

I am inside the Wysing Art Centre, inside the Wysing Art Centre. That is to say, I am inside a computer-generated representation of the Wysing Art Centre, controlling my movements with an old X-Box controller, while standing in the middle of the Wysing Art Centre.

The gallery inside Lawrence Lek’s simulation of the Wysing only contains one exhibit: a virtual copy of Tree Keep, a wooden folly, resembling almost some lost pagan fort, that outsider artist Ben Wilson spent two years hand-carving in an open field outside when the centre first opened, a quarter of a century ago. Tree Keep still stands a few hundred yards outside the doors, now surrounded by trees. But the wood is rotting at the base so it’s roped off, no longer open to be clambered about on as it once was.

In a science fiction narrative, presented in a computer-animated video exhibited next to the aforementioned video game, Lek imagines the Wysing in a post-apocalyptic future, two centuries hence, now an isolated shrine to Wilson’s odd little timber castle. As Tree Keep rots away, Lek sees it rebuilt in less perishable materials: first glass, metal, plastic, finally pixels. Suspended in the permanence of pure simulation, it gleams as if composed of light itself while outside the gallery, the world burns. This future Wysing is now surrounded by a scorched earth, pockmarked by pixellated palm trees.

Shiva’s Grotto(2015) continues a series of Bonus Levels that Lawrence Lek has been engaged in for some two years now. In first-person playable simulations, he has rebuilt the Royal Academy, the Crystal Palace, and Efes pool hall in Dalston. Each one, as he puts it in an essay on his website, is “a continuation of architecture through other means … fictitious, utopian landscapes conceived as site-specific simulations.” For Donna Lynas, artistic director of the Wysing Art Centre, the series is about “how to preserve something that is decaying” and the role technology plays in our emotional bond with a place, or with the memory of a place.

The copy of Tree Keep preserved in Shiva’s Grotto is perfect in every way – almost too perfect – except for one detail. He has omitted the strangely totemic human figures that Wilson carved onto its exterior. I am at a loss to think why – unless, perhaps, there was something he found disturbing in rendering a copy of a copy of a person. What could have a certain charm when rough-hewn in spruce becomes somehow grotesque in the too-perfect glimmer of the digital.

In the real Wysing Art Centre where I stand trying to control my avatar around Lek’s virtual Wysing Art Centre, repeatedly butting my head against walls and getting stuck in corners, the many works on display all circulate around this notion of the “Uncanny Valley”. The phrase was first coined by the Polish-born curator/critic Jasia Reichardt as a translation of Japanese robotics researcher Masahiro Mori’s theory of ‘Bukimi No Tani’.

Mori had sketched out a graph plotting a thing’s attractiveness against it resemblance to real life. He found that certain kinds of humanoid robots and stuffed toys became more and more appealing as they got more and more anthropomorphic. But then something odd happens. Just as the replica reaches the point of perfect likeness – a prosthetic hand, say, or a zombie – the allure axis dips dramatically into horror. There is a narcissism of small differences which makes people recoil before something which comes so close – but not quite close enough – to resembling a real live human. If you’ve ever seen the CGI-heavy (2001) film Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within you may well know the feeling.

It was while watching another film, three years later, that Donna Lynas first experienced the unnerving sensation of the uncanny valley. Polar Express is so heavily reliant on digital motion capture technology that critics like Paul Clinton of CNN found the film “at best disconcerting, at worst, a wee bit horrifying.” Going to see the film with her children, Lynas, likewise, found the Robert Zemeckis picture, “really strange and horrible – but none of us could work out why.”

There’s something of this feeling in Benedict Drew’s film here in the gallery, The Onesie Cycle. A stuttering video in oily black and blue-greys interspersed with elliptical inter-titles, it seem to indicate the dawning consciousness of a latex halloween mask. “It tried speaking,” the text goes, “it couldn’t.” And we see the hollow gaping maw of this Freddy Krueger-esque visor. Still, “it felt” the titles insist, “it was not aware of its status as a by-product of the petrochemicals industry that travelled by container ship.”

It’s not the only mask in the gallery. Sidsel Meineche Hansen took a cast of her face and cast it, flat, in clay, producing something like an H.R. Giger dinner plate. Elsewhere, Estonian artist Katja Novitskova presents a readymade sculpture built around a Babymoov robotic infant-rocker, adapted to run a short loop of recorded nature sounds as artificial supplements to human affection.

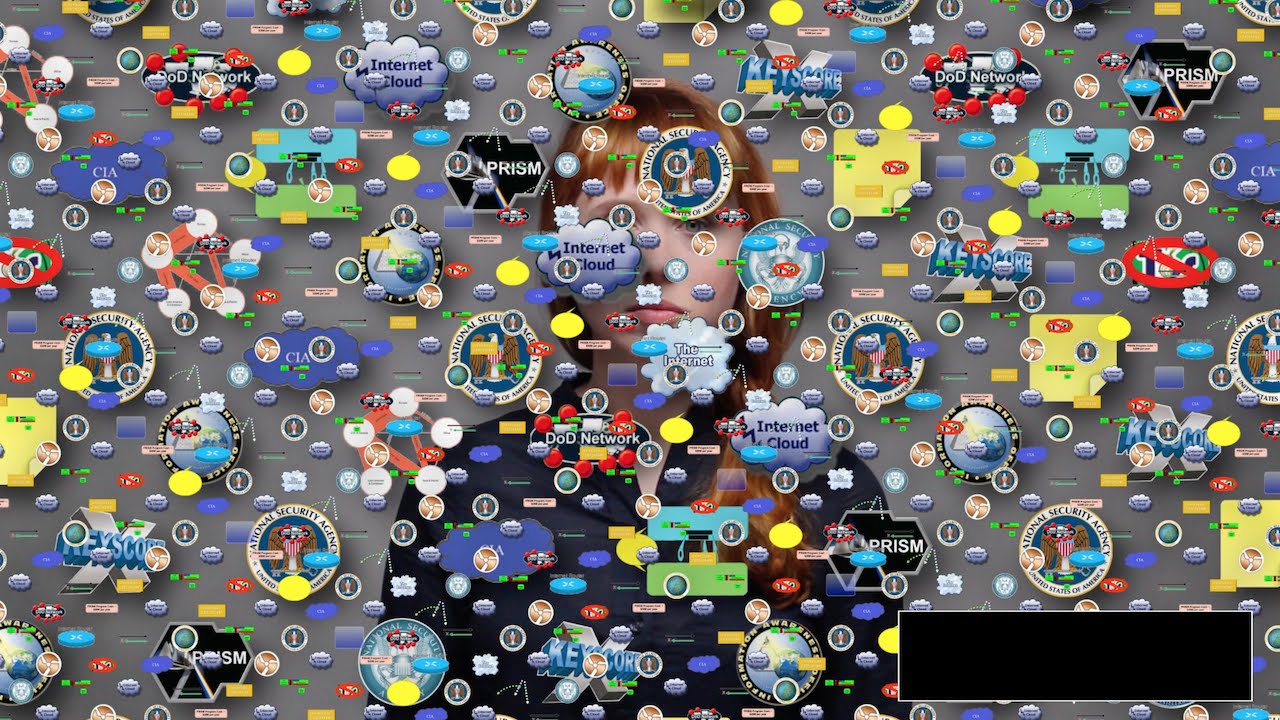

Every fifteen minutes, the relative peace of the space is interrupted by the synthesized voices and crunching digital samples of Holly Herndon’s ‘Home’. The video, by Mat Dryhurst and Metahaven, plays on the big screen at the end of the gallery. Through crashing beats and stutter fx, Herndon serenades the NSA operatives she presumes (post-Snowden) are keeping tabs on her. “I know you know me,” she sings, “better than I know me.”

Donna Lynas tells me she wanted the rude interruptions of Herndon’s video to “build up a sense of paranoia in the space.” For Lynas all these works are dealing with the emotional pull of technology. This, she believes, is why artists have started to get interested in the digital space again. Precisely because it’s no longer about cool tech. Things have progressed to the point where the machines have grown tender, they cast sentimental appeals. Holly Herndon always used to talk about the laptop as the most personal musical instrument ever invented. After all, you can’t Skype your boyfriend on a violin. ‘Home’ is all about the intimate sense of betrayal that the Snowden revelations produced.

The other thing, more recently, was a YouTube video from the DARPA-funded engineering design firm, Boston Dynamics, showcasing their BigDog, a quadrupedal robot military pack mule. Looking rather like a headless deer, the BigDog can scale harsh terrains and even stabilise itself when kicked from the side. It is also, at least, potentially a lethal weapon. A bomb dog, if you will, ready to cock its leg and release the apocalypse in zones no human – and few previous robots – could ever reach.

But here’s the thing: it also looks kind of cute, strangely fragile. When you see the guy in the video kick it in the guts, you feel that same odd wrench in the stomach as if you were watching someone stick pins in a kitten.

Something of this feeling is captured in Julia Crabtree and William Evans’s film Critters, also on display at the Wysing. Another CGI sim, Evans and Crabtree’s film pictures another barren, cratered landscape populated only by a lonely radio telescope, seemingly keening and calling for attention. It flaps its chromed slats and quivers in the wind, desperately reaching out to some alien other that remains forever out of reach, glinting in the light of a dying sun of some hostile far-future Cambridgeshire.

The form of this metal beast was not plucked out of nowhere from the artists’ imaginations. It is based on the arrays that lie waiting and rotting at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory, a kind of graveyard of lost hopes to contact alien life, based in Lord’s Bridge, not far away. We passed it on the drive from Cambridge station to the art centre.

The Wysing’s surroundings are not scorched and cratered, but rather bucolic. Tilled fields and cobbled farmhouses suggest an older world of agriculture and warm scrumpy. But these appearances are deceptive. The local farming industry largely collapsed decades ago. In fact, over 90% of the technology in your iPhone was designed by Cambridge University scientists, many of whom now live in the rural hamlets outside the city. I’m told they call it the ‘Silicon Fen’.

It reminds me of David Cronenberg’s film eXistenZ in which networked virtual realities have relieved the tech industries of the need for urban life so the forests and the farmlands are now stuffed with video game designers and computer engineers.

As we drive back into town from the Centre, passing through a village called Toft I am suddenly struck by déja vu. There’s a shop, a bus stop, the way the road curves and the peculiar bent of the sign all looks uncannily familiar. I have been here before – only last time it was in Kent, somewhere near Tenterden. Surely it’s only the high streets and the big cities that globalisation is supposed to be rendering as facsimiles. A curious feeling starts to take hold: am I in Cambridgeshire… or Kent… or am I still trapped in Lawrence Lek’s game, circling endlessly in a virtual English countryside?

Uncanny Valley runs at the Wysing Art Centre until 8 November