All photos: Ed Reeve for the Design Museum

In the centre of the Design Museum’s subterranean exhibition space is a room constructed from scaffolding and long curling beanbags. When viewed from above, these intertwining cushions resemble the folds of a human brain. It’s an appropriate staging for a show examining the cerebral world of ASMR. The room is busy, but the atmosphere here is tranquil. People are lying on the beanbags, relaxing with their headphones on, watching one of the many TV screens hanging from the ceiling. Each screen shows footage that may trigger a pleasurable physical response in the viewer. This could be something benign like a series of close-miked cooking tutorials or a film featuring a young Björk explaining how television works.

The term ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response) was coined by ethical hacker Jennifer Allen to describe the physical sensations of euphoria, tingling or deep calm that can arise from auditory stimulation. Textural sounds such as whispering or tapping can trigger ASMR, but the feeling is highly subjective. Allen first encountered this phenomenon in her twenties, later documenting her experiences on a health forum in 2009. As it turns out, many other people experienced tingling in this context and it wasn’t long before a decentralised ASMR community grew online. Allen launched the first ASMR Facebook group and lobbied Wikipedia to reinstate the original entry about the phenomenon, after it was found not to have met the editors’ standards. Reproductions of documents from Allen’s archive, which relate to the movement’s early manifestations are displayed on the gallery walls.

ASMR is a child of the internet, flourishing on video sharing platforms such as YouTube and Twitch. Its proponents, otherwise known as ASMRtists, generate content that ranges in genre, from whispered roleplay videos to looping digital animations. In recent years, ASMR has exploded in popularity, with some videos racking up millions of views online. One creator, Gibi ASMR, boasts around 4.24M subscribers on YouTube. Weird Sensation Feels Good: The World of ASMR is the first time that this popular interest which is, conversely, rather niche at the same time, makes itself palatable for an IRL mainstream audience.

In a short trailer for the show, the exhibition’s curator James Taylor-Foster of ArkDes (Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design) puts ASMR’s popularity down to an innate desire for slowness and tactility in a culture dominated by ubiquitous and alienating digital devices. “ASMR came out at a moment in which our smartphones were becoming quicker, bandwidth was becoming more plentiful,” he says. “This strange constellation of things was designed to make our lives more efficient. ASMR harnessed them and, within that, carved out a space for slowness, softness and sweetness.” He goes on to say that ASMR is often designed to help deal with loneliness, social anxiety or insomnia. It satisfies our need for intimacy and is ultimately trying to replicate the feel of human touch.

Aside from supporting Taylor-Foster’s argument for ASMR’s use as self-medication, the exhibition also highlights the phenomenon’s relationship with audio technology. In an effort to make your experiences as sensorial as possible, many ASMRtists employ binaural microphones for their recordings. A few of these are on display, such as the Neumann KU 100 Dummy Head, and great fun can be had whispering into the microphones, especially if somebody else is wearing the headphones.

The London-based artist and researcher Julie Rose Bower takes the opportunity for somatic exploration further with a specially commissioned piece Meridians Meet. Bower’s installation is a live-studio environment where visitors are invited to interact with a variety of tactile materials: a desk with an assortment of brushes, a faux leather mountain range, a cave with multiple suspended speakers urging you to clap into the microphone and listen out for the generated echoes. For those who lack access to microphones or simply have little experience in music technology, it can feel empowering to experiment with sound and texture. Children seem to revel in this participatory element, as do many of the adults.

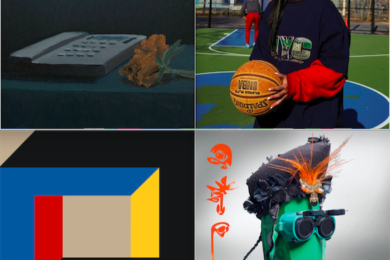

ASMR can also be a disconcerting experience. One of its converse characteristics is misophonia: the emotionally-driven hatred of sounds such as eating, yawning or chewing typically made by other people. Next to a bank of TVs featuring popular ASMRtists, who attempt to define their vocation on camera, stands a sculpture by Tobias Bradford. That feeling//immeasurable thirst (2021) is a disembodied rubber tongue, which writhes and salivates in a perpetual loop. The artificial organ is convincing in its imitation of the tongue and is all the more unsettling for it. Nearby, Marc Teyssier’s Prototype for Artificial Skin for Mobile Devices (2019-2020) and The Voice of Touch (a skin-like silicone tablet that triggers vocal bursts upon contact), from 2022, further invert the generally positive spin of the exhibition and summon a grotesque Cronenbergian future where your Instagram feed can be stroked, pinched and squeezed.

Thankfully, there is a Bob Ross chill out room to placate any dystopian associations. Ross was an American painter and host of the long-running instructional TV show The Joy of Painting. In around thirty minutes, the viewer would be shown how to create a landscape painting step by step. Ross’s soft spoken demeanour, combined with the sounds of palette knives mixing oil paint and brushes scratching canvas, made him the ‘Godfather of ASMR’ in the popular imagination. His show is indeed hypnotic. Despite the banal outcome of the actual paintings, the finished versions of which flank the walls, the programme is a pleasurable watch. At the time of writing, the Bob Ross YouTube channel has 5.27M subscribers and there are plenty of certified Bob Ross instructors who carry the torch forward.

Artists like Holly Herndon, in collaboration with Claire Tolan (‘Lonely At The Top’, 2015), were already treating ASMR as an aesthetic concern several years ago. However, their work reached a largely underground audience, many of whom would have been well versed in online culture. It’s fitting that an institution such as the Design Museum is finally recognising the aesthetic significance of ASMR, just as the movement reaches adolescence and strives for maturity.

Taylor-Foster, who has met the challenge of curating an exhibition largely composed of digitally native content, sees ASMR as an important contributor to the future of design: “ASMRtists are some of the most finely attuned material culture-ists of the world. They understand that all these materials don’t just have a function, but they’re sensory objects. All these questions of close-looking, close-listening and close-feeling are going to become even more important for designers in the coming years.”

Weird Sensation Feels Good: The World of ASMR is at London’s Design Museum until 16 October 2022