In anticipation of the (eventual) release of the Watchmen film, click here to see our gallery of Film Allegories of The Cold War.

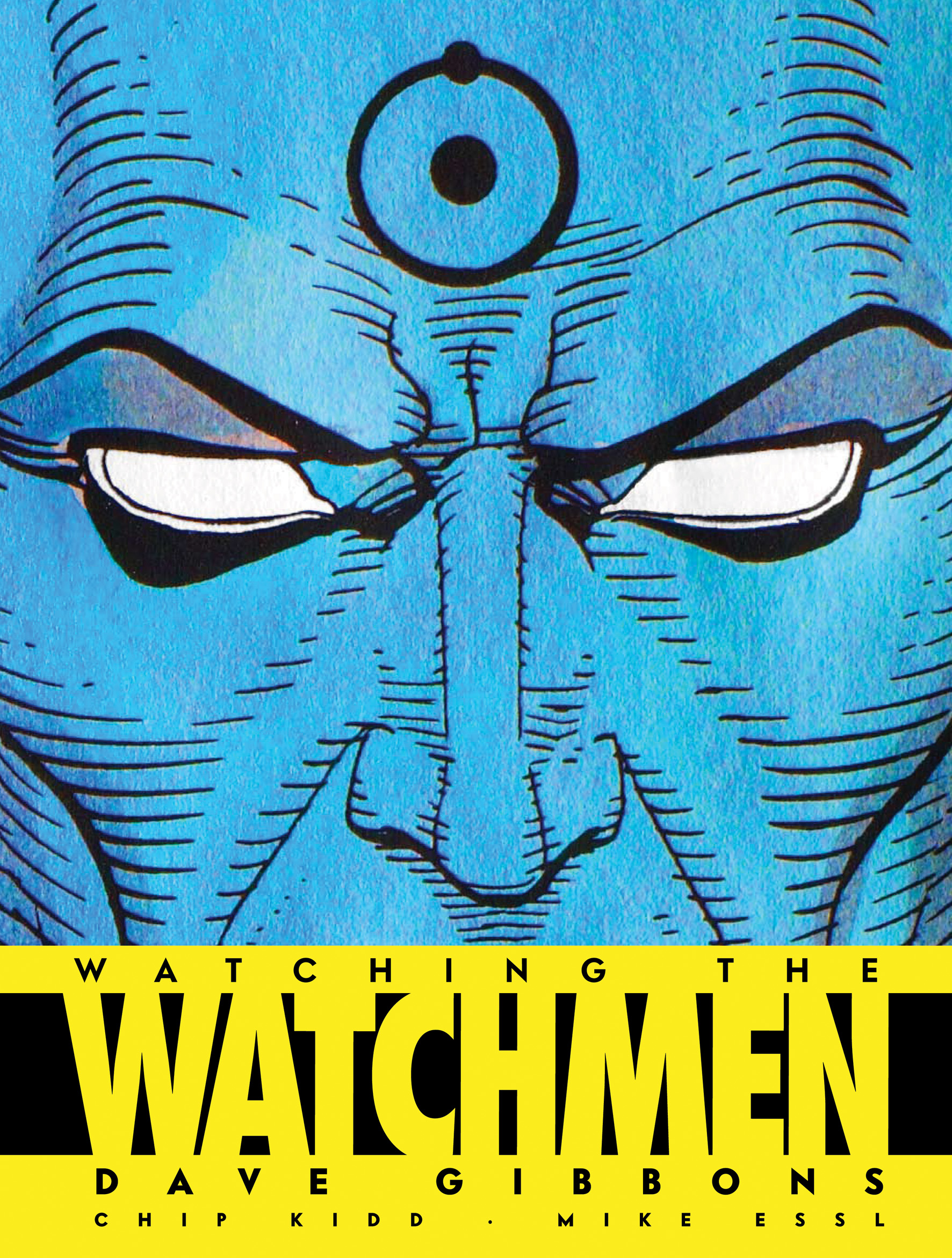

Watchmen is one of the most exalted comic books of all time. Current speculation is rife as to whether or not the over-20-years-in-the-making film adaptation will ever actually reach our cinema screens (Warner Bros. is swamped in a much-publicised legal entanglement over who owns the rights to the movie). There has never been more interest in the comic than right now. In his new book Watching the Watchmen, illustrator Dave Gibbons opens his archives to reveal early versions of the script, original character designs and sketches and very rare Watchmen artwork and posters. He was kind enough to invite us into his world recently . . .

It must be getting a bit busy for you now, I imagine?

"It is, and it has been a bit busy for a while, and I expect it’s only going to get more so!"

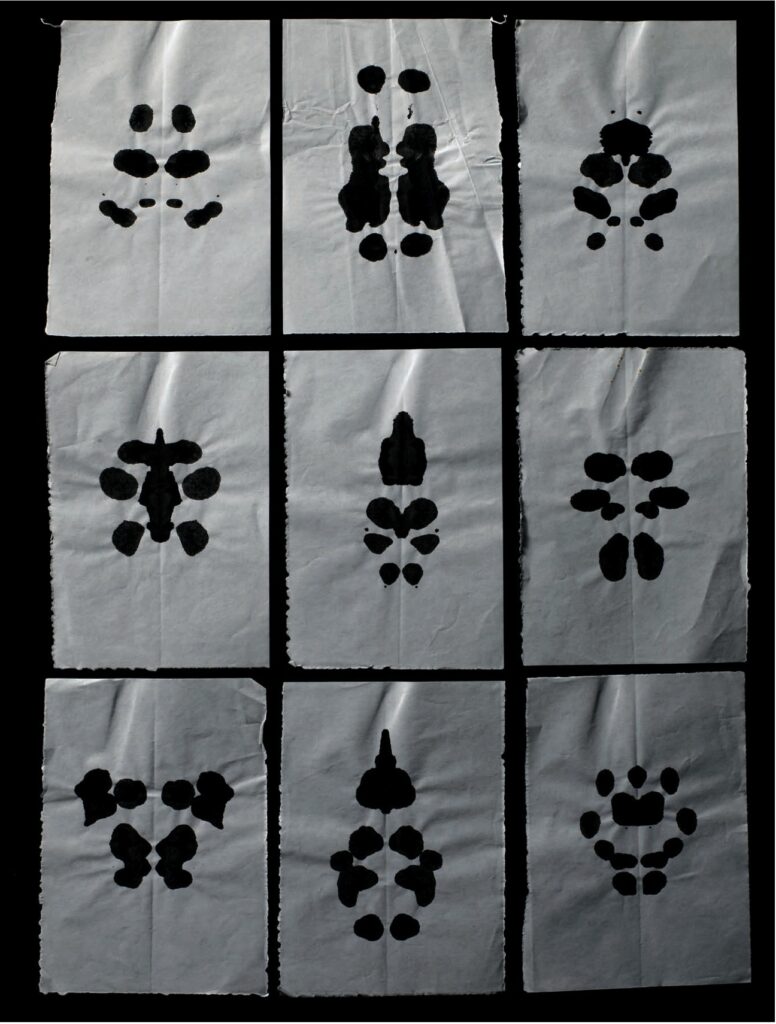

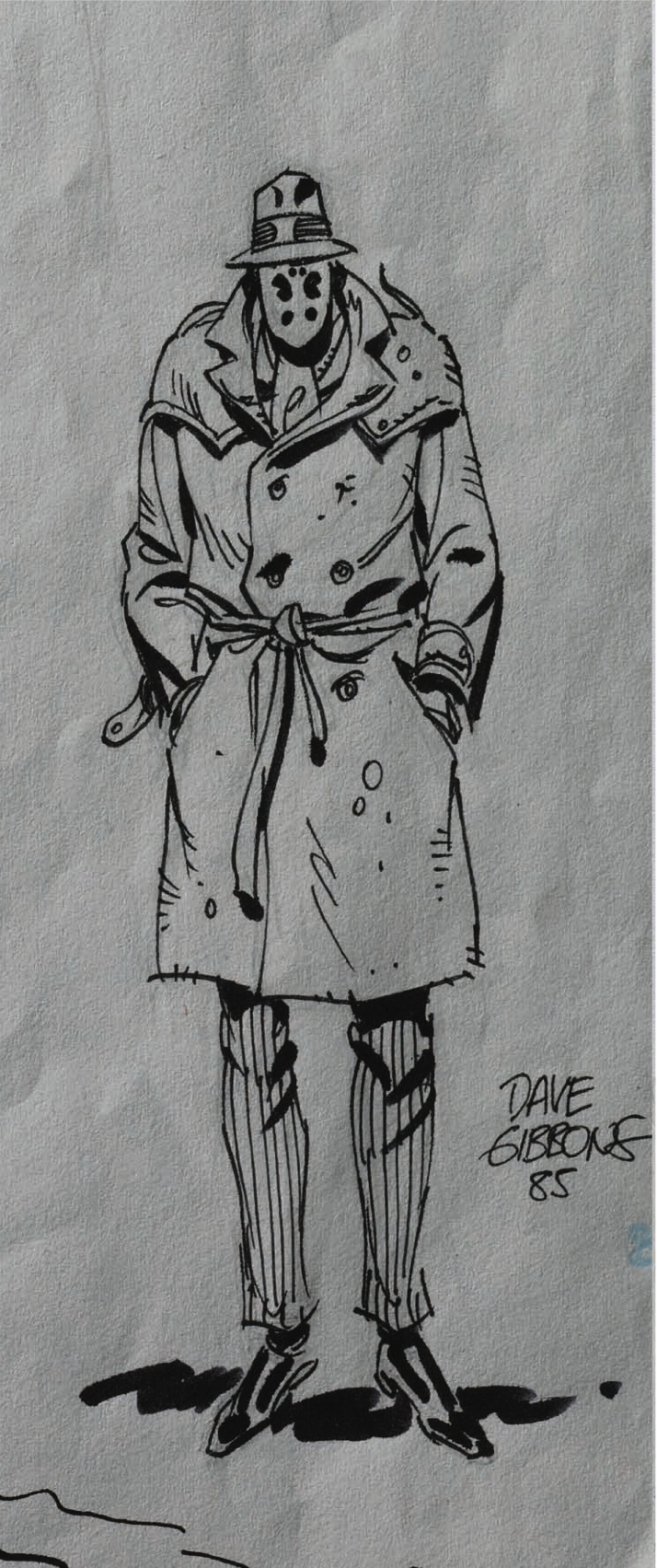

I’ve got a copy of this wonderful big Chip Kidd book that’s just come out, Watching the Watchmen. I do like some of the preliminary sketches that you’ve got in here, they’re quite insightful. I didn’t realise that at one point early on Rorschach was going to wear a full suit of the Dr. Manhattan ink-blot material, instead of just his mask…

"It’s strange, you know. That was an idea that we had early on that I must say when I look at it now seems a bit silly, this idea that he would whip his coat open and kind of flash his Rorschach blots. But we were obviously very attached to it, because it went through many, many iterations, and it’s in a lot of the even quite finished work that I did, so it’s very interesting to look back with hindsight and see what could have been."

There has been a lot of quacking about changes to the end of the story being made in the movie adaptation. Are you completely happy with – er, I mean, well, of course you would be, it’s one of the classics – but, as you say, with hindsight, and having gone through all the earlier material that you would have gone through to compile this book, did you come across anything and think, ‘I should have put that in,’ or ‘This would have worked better than this’?

"I don’t know. We did have the luxury of time when we were putting the whole thing together – quite often with comic book series, you’re told you’re gonna do it on Friday, and on Monday you start work, but we did have a luxury of thinking time beforehand, so I think by the time we actually came to put pen-to-paper, or typewriter-to-paper, in earnest, we’d pretty much thought through everything, and we’d really come up with what we felt was the best solution.

"Of course, once you’re up and running you’ve kinda got to stick to that. There’s the other strange thing that hindsight does, when you’re working on anything, the point at which you start, you’re convinced that it’s gonna be the best thing you ever did, and you then start working on it, and of course it’s work; it’s problems to be solved, it’s compromise. Then you get to the point where you’re sick of the sight of it – by the time you’ve finished it you think it’s probably gonna be the worst thing you ever did. It comes out in print, all you can see are the mistakes and things that could have been better. It then sits in a drawer for years, and you look at it again with somebody else’s eyes, and you think, ‘That’s pretty good.’ Not, ‘It’s the best thing ever in the history of the universe!’ And so, when I look back on what we did then, I’m amazed at our energy and our inventiveness – I hope I say that with modesty, ‘cos as I say it’s like looking back at something somebody else did. I think we probably came up with the optimum solutions. I don’t think we could have done any better. If we’d re-thought it and re-thought it and re-thought it, there comes a time with any endeavour where you gotta say, OK, that’s my best shot, here we go, you know?"

You mentioned that you had a certain freedom, that there were no time constraints during the project. Was that simply down to the nature of the commission?

"DC basically asked us to come up with a treatment for some characters that they had acquired, and Alan did that, and then they decided that perhaps they didn’t want these characters that they’d paid money for to be . . ."

That was Captain Atom and … that lot, wasn’t it.

"Yes, it was all the characters that were published by a sort of a rather a second-string company called Charlton Comics. I think they really published comics just to keep the presses busy in between, you know, paying work from outside. But be that as it may, they decided that probably they didn’t want the characters they’d just paid money for dealt with in such a definitive and often fatal way, so they asked Alan to come up with some new names, and at that point I was on board and we came up with some characters that fitted much better with the kind of story that we wanted to tell. But we were also working, while that was going on, we were also working on a Superman story, which was quite a lengthy story, and so we had to do that, but it meant that when we would want to change the mental scenery we’d spend a day or two and think about Watchmen, so you know that was able to kind of bubble away on the back of the range while we were doing some serious cooking at the front of it – not to stretch the metaphor. By the time we came to do it we really had had a chance to let it ferment – to use another metaphor – and to let it become what it was going to be, basically."

So you had worked with Alan Moore previously then?

"We’d known each other for probably five or six years by the time we came to do Watchmen. And although you’d only have to look at a photograph to see that we’re rather different people [laughs], we got on very well personally and we had very similar tastes in comics there was a lot of shared ground, you know. Alan’s a very visual writer and I think I’m a very literary artist, if you see what I mean, so there was a lot of overlap and we’d really enjoyed working on shorter pieces, primarily for 2000 AD. So it was wonderful to get the chance to work on something that was in much, much longer form. There was nothing else we would rather have been doing, I think."

Whenever I read Alan Moore talking about Watchmen he discusses how you were ‘pushing the boundaries’ with what you can do within the confines of a comic book series. How much of this ‘pushing the boundaries’ attitude can be attributed to you, or to Moore, and was it a conscious decision?

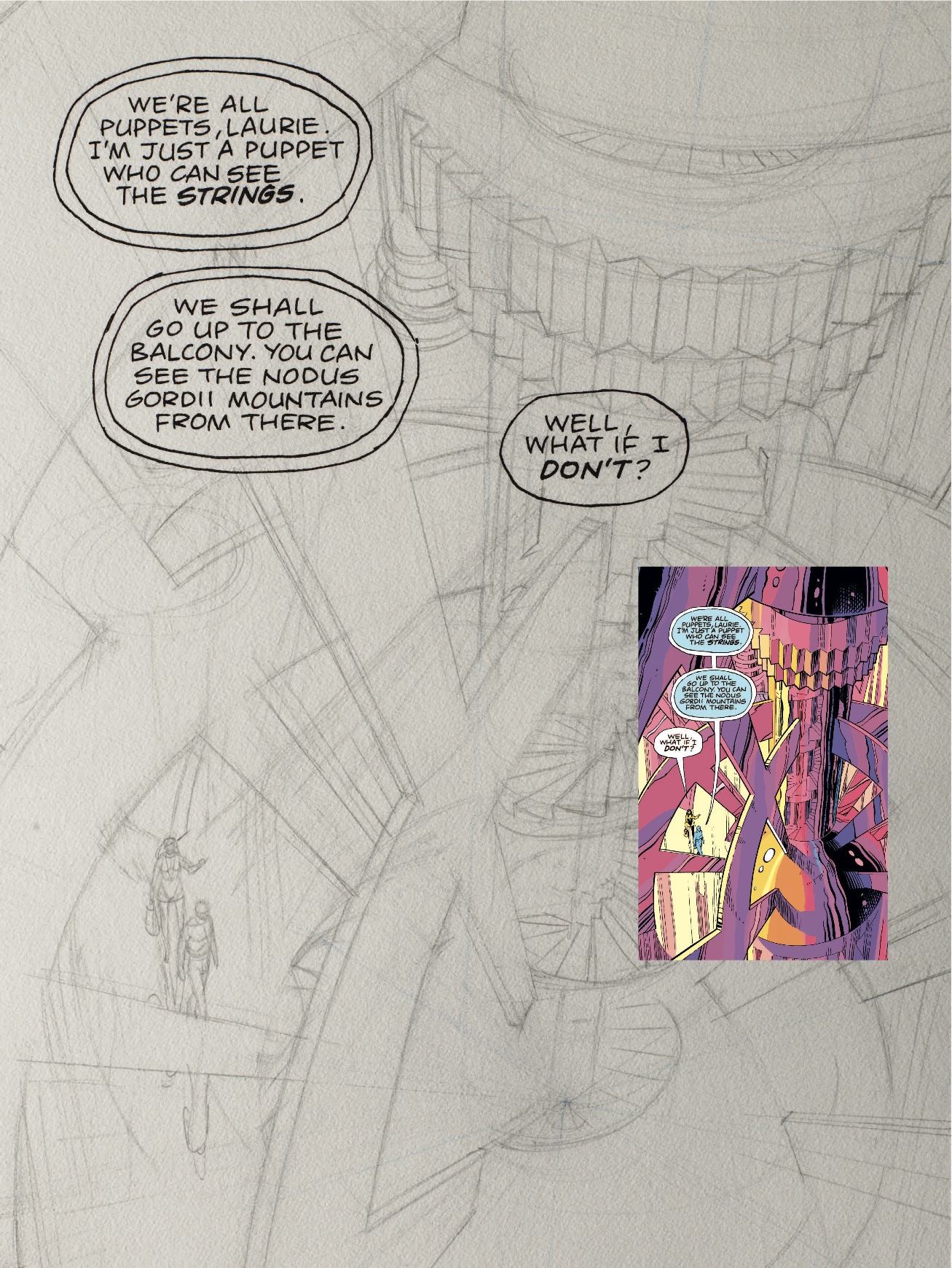

"Collaboration is always a strange thing. As Alan himself once said, if you’ve got a successful marriage, you never care about who bought that CD, or who paid for the CD player, or something like that, but when the marriage comes to an end, that’s when you have these bitter rows about who owns what, and because Watchmen has never ended in a bitter row, we’ve never had to decide who created this and who created that, and I think it’s a bit unfortunate when sometimes collaborators come to that. The best collaborations happen without any ego at all, you both have to be prepared to throw in everything you’ve got, have it shot down if it isn’t for the good of the project, or go with the other person’s suggestion if that’s better. And I’ve always enjoyed collaboration and Alan and I had a particularly happy collaboration and it’s really hard to say exactly what came from where. If you look at our original treatment you’ll see that the story is laid out in great detail, and when I came on board, certainly I was concerned with making all this look good. And so I was responsible for the design of the comic book; the nine-panel grid was a thing that I suggested.

"But to give an example of how the collaboration worked, we had a character called The Comedian who I struggled with for a long time to come up with the look for, and in the end he ended up being dressed in black leather, which is always a good fall back. And I thought, he doesn’t really look very comedic. So just on a whim, I drew a little bright yellow smiley badge on him. Alan saw this and then thought, ‘Ah, that can be the opening of the book – if we throw that in a gutter full of blood, that symbolises that The Comedian is dead’ – it’s his symbol in the blood. And so we put a splash of blood on it, and then we realised that what we had was really a symbol for the whole series, you know, the smiley face was the, or is the, most elementary cartoon. Apparently it’s the least configuration that a baby will smile at, so it’s the ultimate cartoon of the human face. And then to splash realistic blood about it, it shows what we were doing – we were taking what was essentially cartoon fodder and suddenly treating it in a very realistic way, and I had none of that in mind when I drew that little smiley face. And with the pirate comics, that was just a little suggestion that I threw in, is that, ‘Oh, on this world maybe they don’t read superhero comics, they read pirate comics.’ It was just a throwaway detail, but then Alan turned that into something which was a complete kind of subtext of the whole thing. I think you could say that the story was, a huge amount of that was Alan’s. And of course, all the words were Alan’s, because what we would do would be to talk on the phone for hours, three or four hours, and kind of knock an issue together, but from that point on, Alan would write it and I would draw what he wrote, and what I drew would be what got published.

You would do this over the phone, did you say?

"We would talk at great length every time Alan started to script an issue, he’d run by how he thought it might be broken down, then I’d give him my suggestions on that, and then based on the various thing we were talking about – we would both go off into reminiscences, and speculations about how we came through music to comics to childhood experiences to vague feelings about things – somehow we’d come back to the topic of Watchmen again, and this stuff, largely contextual and largely sort of, er, mood as much as anything, would find its way into the finished comic book. We just talked and talked a lot, and then Alan typed and typed a lot and I drew and drew a lot. And then John Higgins – I shouldn’t leave him out – he coloured and coloured a lot, and I very much would talk things through with him, and then just leave him to his own devices. I think good collaborations are like that; you have to trust what the other guy’s going to do, have him put into it, stir the pot, throw in what you’ve got and leave it alone."

You mentioned colourist John Higgins, who was responsible for the muted neon palette. But you did the lettering, didn’t you?

"Yes. I actually broke into comics by doing balloon lettering and I always liked to do my own lettering because it really is such an important part of the way the page looks, and I think actually it would have been impossible or very hard to do Watchmen if I hadn’t lettered my own stuff, because space was very much at a premium, so everything had to fit just so. Whenever I laid an issue out one of the first things I would do would be to pencil the lettering in, or just where the lettering was going to be, the general shape of the balloons, so that I’d know how much space I had left to draw. Now, when it came to the final artboard I would actually physically ink all the lettering in and then draw in the space that remained, so that was really a vital thing, the fact that I lettered my own artwork."

You’re a comic book fan yourself, obviously?

"Yeah."

Are you reading anything at the moment?

"I don’t read anything like as many comic books as I used to, although I get sent many, many more than I used to [laughs]. I’ve always been a fan of comics and when I broke into comics, I was one of the generation whose life’s ambition was just to do comics. Before that, the people you’d get in the field would be people who had aspirations to be novelists, or magazine journalists, or magazine illustrators, or fine artists who were just slumming, doing comics until something better came along. In most cases, nothing better – in their terms – ever did come along, and there have been wonderful comic artists who’ve worked in comics like that, but my generation, we really just wanted to do comics. That’s all I ever aspired to do, I’m happy to have spent my working career doing that. When you ask people for their favourite comic book influences it’s a bit like the usual suspects . . ."

No! No, no, no, that’s as awful a question as, ‘What’s your favourite band?’ Terrible question. No, I was wondering if there’s anything recently that you’ve read and gone, ‘Hey, this is . . .’

"Well, something I read last week, it’s a book called Alan’s War, which is a graphic novel by a guy – if I can scuttle over to my shelf I can tell you exactly who it’s by. It’s by a guy called Emmanuel Guibert. It’s a true-life story of a guy in World War Two, and that’s a fascinating book, so that’s the one that springs to mind. I do read a lot of mainstream stuff, I do try and keep up with what my friends are doing. Of course, with the Internet it’s now so easy to see what’s going on."

Did you read Joe Sacco’s Palestine?

"No, I have seen it, do you know I never got round to reading that. There is a thing that happens, and part of being a comic book fan is that when you’re at school you were told, ‘Oh you should read the Classics, and you should read this,’ but you just preferred your comic books. And Palestine, I have to say, is one of those books that enough people have said, ‘Oh you’ve really got to read this,’ that actually the anarchic comic book reader in you thinks, ‘Well I don’t want to read it just ‘cos you say so, I’ll read it when I want to read it.’ So that is something … It’s a bit like Persepolis, that I know I should read but I haven’t actually got round to it yet, because too many people have told me to. But, one day I will."

I tell you, a friend just gave me Bone to read, and . . .

"Oh, Bone is great! Actually I was just re-reading that on my iPhone, ‘cos you can now download it from the iTunes store, which is quite a novel way to – er, yeah, I mean, Bone is an absolutely charming thing, and again it’s so well done in technical terms that it’s a seamless and very entertaining read, definitely."

You can download it onto your iPhone. That’s amazing. I want an iPhone. What with e-Books and other emerging technologies, what do you suppose is the future for the comic book and the graphic novel?

"I think the slim monthly pamphlet, the comic book as it is known – the real problem is that, in comics, I don’t think so in other fields, but most of the terms we’ve got are grossly inaccurate, because most comics aren’t actually comic, and most comic books as I say are pamphlets or magazines rather than books, and most graphic novels, although they may be graphic, are not novels, they’re just big comic books. So, erm, I think that possibly that monthly format will dwindle, I mean they are very expensive now. I think most of the publishers in truth look upon the ‘graphic novel’, the book collection, as being the final product. You can reach a much bigger market with that. People will always want to have books on their shelves, people who love books, love books. They love the object, they love a well-printed, well-produced book. I think increasingly though, for cheap entertainment, people are turning to digital delivery. Reading a comic on the iPhone is not quite the same experience as reading a book; however what it does solve is the problem of, ‘How do you get paid for it?’ That’s always been the problem, how do you sell somebody something online for a quid or 50p? Certainly the iTunes store seems to be the way to do that, so I think that’s going to be something to watch in the future."

Now that our conversation has drifted into technology, perhaps you can answer once and for all whether or not there is any truth to the rumours that there is a sequel planned for Beneath A Steel Sky [legenday mid-’90s point and click cyberpunk game]?

"Funnily enough, about half an hour ago I was talking to Charles Cecil of Revolution Software, who were the company behind that. I don’t think so. We’ve sort of joked about it. We did actually work out a whole storyline, because I was involved with Beneath A Steel Sky doing artwork and designs and having some story input, and I actually worked out a whole way that the story might go. Whether that will ever see the light of day, I don’t know. I have been doing some stuff with Charles – not very recently, but doing some artwork for him. I don’t play computer games to any great degree, but there’s a similar feeling in that field to the one in comic books. A lot of people who are in it got into it ‘cos they love playing games, and they were writing their own games when they were kids, so it is a field that like comics has a lot of enthusiasm and creativity in it. I wouldn’t rule it out."

You’ve got the Martha Washington Omnibus coming out soon, right?

"That was something that Frank [Miller] and I had done over the past 20 years, kind of in-between doing other projects, and it’s amounted to something like 500 pages, getting up to 600 pages. So it’s quite a body of work, but it’s never been available in one place before, so I’ve been doing some work on that. I’ve done some introductions to the chapters and Frank’s written an intro to it, and I’ve done a new cover, and we’re gonna try and bring together in one place everything that’s been printed that features Martha. That (I hope) will be out around, I don’t know, maybe March or April? It’ll be an oversized book, what we call the ‘Absolute’ format, which is that larger format that Absolute Watchmen is in."

That lush slip-case edition?

"Yeah, it’ll have a slip-case, and it’ll be rather a nice production. Something that hopefully lovers of elegant books will treasure."

What do you think of Frank Miller’s loonier, more right-wing Batman he’s done for DC’s All Star series?

[Laughs.] "Well, the thing I like about Frank is that he doesn’t do what’s expected, and he doesn’t mind upsetting people. I don’t necessarily like everything that he’s ever done, but I always admire his guts and I think that the, the kind of the follow-up that he did to The Dark Knight Returns that was out maybe, I dunno, five or six years ago [The Dark Knight Strikes Again, published 2001], I know it rubbed a lot of people up the wrong way, but I thought it was tremendously bold and fearless and that’s really what I admire about what Frank does. Again, as I was saying earlier, comics is about words and pictures, and Frank knows just what to put on the picture track, and just what to put on the sound track, and I’ve really enjoyed our collaborations together. Completely different in feel than working with Alan, but, no, Frank is one of the real modern geniuses of comic books, I think.

He has got The Spirit movie out at the moment.

"Which looks interesting – I mean, it’s obviously very, very close to the sort of look that Frank has had in Sin City. I think, again, the thing that people often overlook with Frank’s work, is that he has got a very good sense of humour. It can sometimes look a bit grim and forbidding on the surface, but I hope that his particular sense of humour will come through in The Spirit adaptation, and that people will find it amusing…"

Inevitably, as we are now onto adaptations, I must ask about the Watchmen movie. One of the things I got from the trailer is that, as with his adaptation of 300, Zack Snyder’s movie looks incredibly slick, which I’m not sure if that’s in keeping with the spirit of the Costumed Adventurers, who are basically just a bunch of thugs, going around beating people up…

"I don’t know if ‘thug’ is the word that I would use for all the characters in Watchmen, although in a few cases I think that’s apt. And I don’t know if I would describe Zack’s work as slick. I think he’s got a wonderful visual sense and what I got from seeing a rough cut of the movie was that it’s very rich; there’s a density to it, there’s a feeling of formality to it as well. I’m not a technical expert on films, but Zack shot it all with a single camera, so in other words, everything was composed on a single camera, lit for a single camera, and the set-up was changed to do cut-aways, and different views of the same scene. I deliberately drew the comic book in a very considered, formal style. I think that carries over into the comic book. And because of the information he’s having to get over, travelling around in space and in time, he’s had to be very specific about what he includes in the images and so it’s got a very rich, kaleidoscopic kind of feel to it."

Does God live in Alan Moore’s beard?

[Laughs.] "I don’t even want to think about what lives in Alan Moore’s beard, or even what kind of god we might be talking about, but I think as somebody on an earlier interview said that I can say pass to any question, I will say ‘pass’ on that."

‘Watching the Watchmen’, published by Titan, is available in all good bookshops.

‘The Spirit’ movie is in cinemas now.

‘Watchmen’ the movie, ought to be released – legal battles with Twentieth Century Fox aside – on March 6th.

In anticipation of the (eventual) release of the Watchmen film, click here to see our gallery of Film Allegories of The Cold War.