“What you’ve just been listening to is the ultimate in recorded sound,” said Jeffrey Watson, presenter of Australian TV series Towards 2000, after a short blast of classical music. “It’ll make all conventional disc and cassette systems obsolete. It’s dust proof, scratch proof, digitally recorded, read by a laser and it’s called the compact disc.” As he spoke, Watson held up a CD, shiny data layer side facing the camera. “And that’s it, the biggest revolution in the recording industry since the long-playing gramophone record.”

On 1 October, 1982, the first album to be released on CD, Billy Joel’s 52nd Street went on sale in Japan, Sony’s CDP-101 CD player hitting the shelves on the same day. Early the following year, they hit Europe and North America as record labels made bigger selections of music available on the format.

Towards 2000’s heralding of the CD as the dawn of a laser triggered high-fidelity age wasn’t unique. On a Tomorrow’s World feature, Kieran Prendiville marveled at the six billion microscopic pits and spaces encoded with music. “In reality, the track on this disc is two and a half miles long.”

Like Watson, Prendiville talks up the robustness of the format: “You don’t have to worry about grubby fingers, or even scratches,” he says, before scratching the disc, but notably not then putting it in the CD player. More boldly, a BBC Breakfast presenter smothered a CD in honey and coffee, wiped it down then played it.

Quite why anyone needed a breakfast-proof music format is not really addressed, and anyone who’s owned a CD Walkman will know that while they might not be disrupted by honey, they definitely will be by running. As someone who started listening to CDs in the early 2000s, the ones I had never seemed quite as indestructible as those BBC Breakfast got hold of two decades earlier – a couple of months packed in a backpack or left face up without their case would make them start to skip.

That BBC Breakfast feature makes another point though, one which appears throughout all these TV spots. “The hi-fi world has become something of a graveyard for bright ideas that came to nothing,” the presenter says, listing quadraphonic records, eight tracks and L-cassettes as music fads that went nowhere. John Atkinson, editor of Hi-Fi News counters that the CD represents “real” change.

To an extent, he was right. The CD has become the dominant physical music format. According to BPI figures, 2021 saw the lowest drop in CD sales in three years, 12 per cent lower than predicted and apparently boosted by “CD friendly releases from superstar artists such as Adele, Ed Sheeran and ABBA.”

The BPI figures tend to focus on the surge in cassette and vinyl sales – 2021 was also the 14th consecutive year of growth in vinyl sales and an eight per cent increase on the previous year. A 20 per cent increase in tape sales was their ninth consecutive year on the up. However, looking at the actual sales numbers rather than growth and decline, CD remains the most popular physical format by some distance. 14 million CDs were purchased in 2021 versus five million vinyl LPs and just 200,000 cassettes.

The audio CD originated in the failure of another format. In the 1970s, developers at Phillips were working on optical discs capable of storing audio and visual information, Kees Schouhamer Immink, a Dutch engineer involved in the project, wrote in an essay titled The CD Story, first published in the Journal Of The AES in 1998, that research management at the time dismissed audio only discs as “far too simple and not worth the effort.” In 1975, Phillips launched Laservision. Just 400 units were sold, according to Immink, and 200 returned because customers mistakenly thought it’d let them record rather than just play back video. “It was a monumental flop.”

Eventually, in the late 1970s, Phillips joined up with Sony to work on the new disc format for sound. According to Immink, the “physics” were provided by Phillips and the “digital audio experience” by Sony. The collaboration was crucial to the CD’s success. Where previous audio-visual innovations, such as VHS vs Betamax, had confusing standards and compatibility issues, the CD evaded these – any CD was compatible with any player.

If CDs marked a new era, it is perhaps as much in the way they suggest specific ways of interacting with recorded music as in questions of fidelity. As the Towards 2000 coverage noted: “You can select your own sequence in advance, so you can play [the tracks] in any order you want.” The fact CDs can be programmed, and tracks easily skipped, is perhaps their most significant feature when it comes to their legacy. They loosened up the album as a fixed document. You could more seamlessly put one track on constant repeat, skip the interludes you didn’t like, or imagine a hypothetical ‘better order’ for your favourite album.

They prefigured many of the key features we’d associate with mp3 players, iPods and, most recently, streaming. CDs introduced randomization and customization to a physical format, and that bled through into later music technologies. It presented a possibility to mess with sequence which artists and labels embraced and explored.

On their third album, 1999’s Guerrilla, Super Furry Animals slipped one of their best songs, ‘Citizens Band’, into the pre-gap, that is, the neverzone before the album proper. Autechre pulled the same trick, in the same year, on EP7, hiding an eerie six minutes of intricate sound design which seems years ahead of its time, and then three minutes of silence, before ‘Rpeg’. They did it again, including the untitled track in the pre-gap to the fourth disc of EPs 1991-2002.

Pre-gap tracks are a CD-specific phenomenon, paralleled only by DVD Easter Eggs, or hidden levels in a computer game. On the one hand, they’re only possible digitally, on the other, they seem to be an attempt to add some mystique to a circle of plastic. They are a defense of the physical medium because it is impossible to rip them to your computer. Finding them meas having a bit of extra knowledge about the artist, uncovering a hidden layer of depth others hadn’t noticed.

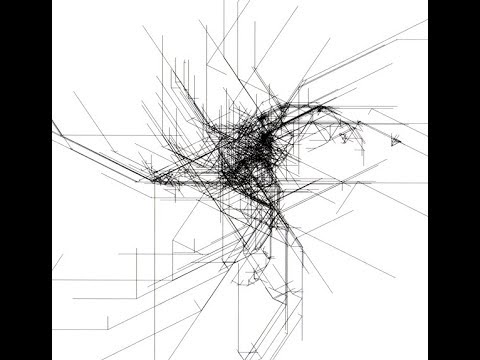

Earlier, experimental artists took even greater strides into the CDs unique sequencing possibilities. Otomo Yoshihide’s 1993 release The Night Before the Death of the Sampling Virus is a fluctuating voice collage designed specifically for the medium. Its 77 tracks are tiny, most less than a minute, few going above two. The listener is encouraged to hit the random option on their hi-fi. “To play this release in random mode is to allow the SAMPLING VIRUS to regenerate, to mutate with near infinite possibilities.”

Eccles, UK-based experimentalists Stock, Hausen, & Walkman encouraged listeners to do something similar with their debut album, Giving Up. From the release notes: “The Original CD had 60 ID points deliberately inserted in the middle of a lot of the tracks so that random play would cut the music up and present the listener with a new and unique ‘remix’ version if desired.” There were things you could do with a CD, that you definitely couldn’t do with a tape or LP.

More recently, London-based composer and performer Jonathan Higgins uses hand modified CD players to explore the materiality of CD sounds. His albums, such as the soon to be released Good Thanks, You?, engage with the particular nature of the glitch in CDs, amplifying and remolding the jolts that happen when one does go wrong. It’s as if he’s trying to give voice to the pits and spaces that allow a CD to produce audio. But, while there have been and continue to be artists working with the CD as a material, there’s yet to be a Disintegration Loops or a Selected Memories from the Haunted Ballroom made from CDs, in the sense of a release which has jumped out of experimental circles. Why is that?

Part of the explanation could be the relative ubiquity of the CD outlined above. It’s so familiar as a physical medium that it doesn’t have the distance to be exoticised or fetishised. Another explanation is less about distance and more about the object itself.

Will Straw, in a 2009 journal article titled In Memoriam: The CD And Its Ends, suggested the CD was becoming a victim of its own noise reduction success. “When the materiality of music playback technology no longer shapes music’s meanings in recognisable ways, that technology becomes little more than a temporary host for music.”

Both William Basinski’s and The Caretaker’s work are deeply storied, no doubt that’s a big part of what’s allowed them to jump beyond the experimental underground. Their choice of media: tape and vinyl respectively, have a lot of the audible materiality that Straw mentions. The imperfections of the materials they use weave into the stories that surround them. The surface noise adds a layer of history and a layer of nostalgia. The fact Higgins’ work relies on hacked CD players shows the lengths that need to be gone to make the materiality of a CD apparent.

Just as much as cassettes or LPs, CD’s have qualities and quirks. And they also have affordances that make them ideal for certain kinds of music. But, despite being 40 years old, and gradually being replaced by downloads and streaming, they don’t seem to trigger the same nostalgia and whimsy.

The Quietus has a regular cassette reviews column (which I write). I’d venture that its very existence says something about the CD. Spool’s Out is not the only column focused on the tape underground, indeed two other music publications have started regular cassette features in the last twelve months (although Bandcamp Daily also had a dedicated tape feature prior to its latest incarnation). These columns celebrate the underground networks that have sprung up around the cassette as much as the music that’s released on them. As far as I’m aware, there’s no similar dedicated CD column. For all its unique qualities, the CD doesn’t capture the imagination, or at least critical bandwidth, in the same way.

Yet, there are signs the underground is increasingly embracing the CD. A few years ago, heads of DIY labels started bemoaning the rising costs of making tapes. CD had become more viable, which is somewhat ironic, given its past reputation as an inordinately expensive format relative to the cost of production. Kyle Devine notes in Decomposed: The Political Ecology Of Music that once mass production had been perfected, CDs were 75 per cent cheaper to make than vinyl LPs, yet these economic savings “controversially, were not passed on to consumers.”

Similarly, the BBC Breakfast segment on CDs noted that players would cost about £500, individual CDs £9 or £10. For the time being it’s more likely to be a gadget for the rich”. No doubt laptop computers with CD burners and CDRs started to redress that balance. In terms of sheer economics, there are signs CDs are becoming an increasingly prudent way to release music, and not just for ABBA and Adele.

Kate Carr is a sound artist and composer whose music frequently works with field recording and intricate uses of electronic and acoustic instrumentation. She also curates the Flaming Pines label, dedicated to experimental music and sound art. Many of her releases, of her own work and on the label, are published physically on CD. For her, it’s a pragmatic decision.

“To be honest I am not really someone who has a huge emotional or nostalgic attachment to any physical format,” she explains over email. “CDs are simply a practical choice for me, I can get a small run done, more people buy them than tapes, at least for Flaming Pines I find tapes quite a bit harder to sell than CDs, and they are cheaper to post in the UK system as well, being thinner.”

Carr suggests that the CD is appropriate for the kinds of music she releases: intricate, detailed, and perhaps best experienced not disrupted by needing to be turned over.

“I think they probably are better suited for very subtle and quiet field recording type works,” she continues.

“The thing I find most interesting about the whole thing regarding format and materiality is that even though a large proportion of people may listen almost exclusively digitally to music, there is still a sense that if something doesn’t have a physical release it is a less substantial album. Even people who would never listen to CD, tape or vinyl I think still assign value to an album existing in a physical format. That physicality kind of haunts the release, giving it a substance even in its digitality. For me, given this, CD offers a really easy and practical way of providing this physical option.”

Perhaps, however, this practicality is also part of why CDs don’t seem to trigger the same warm affection as cassettes or LPs. Maybe they’re a little too digital and functional. In the wake of the vinyl revival, there are environmental reasons why CDs might be a way forward. They have a lower environmental footprint than an LP, at least in terms of the audio objects themselves, things can get a little more complicated if you include the packaging.

“But polycarbonate [which CDs are made of] is less toxic than PVC [which vinyl records are made of] and CDs also use less plastic per unit than LPs: A CD itself weighs 15 grams, while an LP is typically about 100 grams,” explains Devine in Decomposed.

Of course, and as Carr suggests, some music just seems to fit better on CD. The fidelity and relative noiselessness make it popular with jazz and IDM. Its uninterrupted durations are well suited to minimalism, the perfect physical vehicle for Julius Eastman’s Femenine, for instance. Age and context undoubtedly also play a role. As someone who got into music in the first decade of the 21st century, my music tastes started with pop punk before a sudden left turn to post rock. The CD still seems the perfect format for both.

Blink 182’s Enema Of The State makes a lot more sense to an angst riddled, socially unsure teenager if you can skip straight to ‘Adam’s Song’ and keep it on repeat for a while. Likewise, Greenday’s Nimrod can be the soundtrack to juvenile japes if you follow the numerical order from ‘Nice Guys Finish Last’ into ‘Hitchin’ a Ride’, or heartbreak if you start on ‘Redundant’ then skip direct to ‘Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)’.

Labels such as Kranky or Constellation, meanwhile, made the CD an art form. Take Labradford’s Mi Media Naranja released in 1997. A nocturnal world of shimmering electronics and reverb drenched guitar twang, each track flows into the next while remaining its own distinct entity. They accumulate into an atmosphere that fills your surroundings with charred effervescence. The album has a vinyl release as well, but the thought of stopping to flip it half-way through seems unthinkable. Similarly, streaming it on a phone or computer, with all the potential distractions that could entail, risks diluting the effect. Early Stars Of The Lid albums, or Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s F♯ A♯ ∞ have a similar feeling. Once you’ve heard them on CD, played through without interruption, it’s hard to imagine them otherwise, however much vinyl crackle and warmth might be on offer.

There’s an interesting paradox with the CD. While they’re the ideal format for customizing the listening experience, disrupting the album’s flow, or entering an endless repeat, they’re also the format par excellence for the album as a comprehensive, self-contained unit to be played from start to finish. The Necks are a perfect example of a band whose music seems made for CD. Similarly, Thomas Ankersmit’s stunning electro-acoustic world from 2021, Perceptual Geography, made clear the CD is the ideal physical format to convey it. As the liner notes say: “This is a digital-only release (CD and download) because the “ear tone” material can’t be adequately transferred to vinyl.”

They might not have the specific imperfections that attract so many of us to tape or vinyl, yet CDs are a unique format with all manner of possibilities embedded into them. More than just a curious stepping stone in the digital transition, for better or worse they facilitated a specific way of relating to sound that could be as playful as it was functional.