“When Rainer suggested I work with him, I was thrilled, because he was a young man with a brilliant record. I loved the things he’d done. People think of him as just a motorcycle lad who took too many pills, fucked boys, and jumped out the window. It’s not so. He did all those things, but on the side he was a really good guy. He was a brilliant director; he knew more about the camera than even Cukor or Visconti.” — Dirk Bogarde, Interview, 1991

Rainer Werner Fassbinder was just three months old when the Nazis surrendered in 1945. The unspeakable atrocities undertaken by the National Socialist Party were always there in his subsequent art – though, mostly, implicitly. Growing up in Bavaria under the long shadow cast by the Third Reich, there’s a sense Fassbinder could never rest during his 37 years because of the horrors committed on German soil. That would have been the case for most of his contemporaries.

“Our generation in Germany is skeptical about the culture of the past,” Ingrid Caven, the director’s one-time wife and Fassbinder perennial, told Cahiers du Cinema in 1993: “All that German culture accomplished didn’t prevent people from turning into murderers. That’s why there’s all this denial. We had to find new ways of expression. We needed to recognise that German culture is unthinkable without German-Jewish culture. Germans, whether they are Jewish or not, must understand this. To us, it was impossible to simply go on as before, to forget what happened”.

It may come as a surprise then that Fassbinder’s theatrical company only ever made one film set during the Second World War: Lili Marleen in 1981. Even the films of the BRD trilogy are all post war pictures; The Marriage of Maria Braun starts at the end of the war, while an affair with Goebbels is alluded to briefly with the titular character in Veronika Voss, back when her career was at its zenith, a singer loved by the Nazis by implication. Despair is an oddity in that it’s the only Fassbinder picture set in the run up to 1939 (although his epic 15 hour 1980 serial Berlin Alexanderplatz returns there). It’s an anomaly for lots of other reasons too, which we’ll come to later.

If he wasn’t making films about Hitler directly, then Germany’s past is often the elephant in the room in Fassbinder’s melodramas. Life continues as normal and nobody talks about the war, but everybody remembers – how could they not? Themes of power and cruelty are explored in most of RWF’s films, usually derived from situations contrived by the autor, such as when a German cleaning lady marries a Moroccan immigrant two decades her junior in Ali: Fear Eats The Soul. Emmi goes to a bar one night for a glass of coke and sits at a table on her own, and she comes home with a husband. Despite her apparent happiness, she has to face down racial intolerance from family, work colleagues and the racist at the local store (Fassbinder takes the technicolor melodrama of Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows and further subverts its central premise).

In one scene Emmi and Ali visit Hitler’s favourite restaurant in celebration of their conjugal felicity and are embarrassed by their own seeming lack of sophistication. The 1974 movie is bleakly funny and offers pockets of hope, at least where Fassbinder’s weltanschauung is normally so cynical. While we are supposed to root for the unusual couple, his contempt for the rest of West German society is clear.

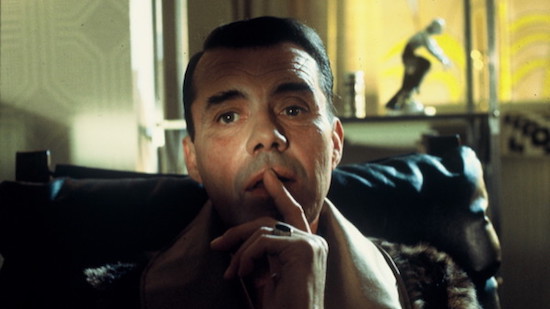

Despair’s leading man Dirk Bogarde certainly thought so. Speaking candidly to Interview in 1991, the actor who plays Hermann Hermann in the picture, talks of his relationship with the troubled director, and his disdain for RWF’s hangers on, who he felt encouraged the debauched lifestyle that would eventually kill him. He told Gary Indiana: “Rainer and I became enormously good friends. As I’m very ordinary and proper, I disapproved of his group. I didn’t like them because they were destructive to him. But I was devoted to him, and respectful. Couldn’t stand his mother. One day Rainer said to me, after some conversation I had had with her, ‘Never, never, Dirk, ask anybody of your age-group here what they did in the war.’ He loathed the Germans, vehemently. I had a room in the Bauscherhof hotel in Munich, and Rainer came around one night for a script conference or something. He was appalled when he got off the elevator; he was shaking – well, he often was shaking. He’d have taken a little white pill or whatever, and I said, ‘What’s the matter? Sit down.’ So he sat down and said, ‘I’ve just seen the elevator doors. Have you seen them, the gold doors in the elevator? They’ve all got swastikas scratched on them from somebody’s key.’ He couldn’t believe it. He said, ‘You see, we’ll never eradicate it.’ And he was beginning to get weepy. I said, ‘Come on, let’s pull ourselves together.’ And I gave him a huge… well, half a bottle of brandy, I think, and he staggered out into the night.”

It’s interesting that Bogarde saw Fassbinder as a victim at the mercy of his entourage. The actors who worked with him are often described as “victim collaborators”, pushed to the limit, sometimes violently so, and hostages to his notoriety, forever fearful of being ejected from the company to disappear into obscurity. In Chaos As Usual: Conversations about Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the actors parrot his almost cult-like mantra that “working must be fun”, though claims of button-pushing, of twisted nipples on set to make actors cry for dramatic effect, and even tests for proficiency in Latin – it’s a working environment that doesn’t sound entirely agreeable or healthy. “Very authoritarian” is the expression used by his longtime cinematographer, Michael Ballhaus.

In the same Interview tête-à-tête, Bogarde, born Derek Jules Gaspard Ulric Niven van den Bogaerde, speaks of seeing Heinrich Himmler’s lifeless body at the conclusion of the war. Laughing, he confirms: “Yes, I did. Just after breakfast, too. Yes, he was lying there in the bay window of a little parlor in Luneburg. I was absolutely amazed, the wretched little beast. He’d taken cyanide. Terrible pair of old army boots on, hairy shins, and a blanket. I thought, God, you really have been the bogeyman of all time.”

Bogarde joined the Queen’s Royal Regiment as an officer in 1940 and eventually attained the rank of major in the Air Photographic Intelligence Unit, awarded seven medals for his five years service. His division helped liberate Belsen in April 1945 which he described as being “like looking into Dante’s Inferno”. He went on to become one of Britain’s best-loved and most uncompromising actors.

In the 50s he became a matinee idol, which seemed to bore him. During the 60s, his choices of film became far more interesting, working with arthouse directors like Joseph Losey and Luchino Visconti. While Fassbinder was openly bisexual, Bogarde remained closeted throughout his life – after all, he was 46 by the time homosexuality was decriminalised. There are coded pointers in films like The Servant from 1963, where Bogarde put in perhaps his finest performance as the sinister manservant, Barratt, though he never officially came out.

By the time he came to film Despair in 1978, he was all but through with acting, mostly spending his days writing novels and memoirs instead. He made a few TV movies and was coaxed out of retirement for one final film alongside Jane Birkin in Daddy Nostalgie in 1990, but otherwise Despair would have been the full stop to a great body of work as a movie actor. In terms of who was involved in the screenplay, it could hardly have been more illustrious.

The budget was massive for an RWF film too. According to E.A. Berry’s blog In a year with 44 films, Despair cost six million Deutsche Marks compared with Chinese Roulette’s one million. Most Fassbinder productions cost half that.

The director devalued his own productions by refusing to adhere to the unwritten rules of the market, namely he brought out four films a year instead of one, including TV productions. Despair is an adaptation from the book of the same name by Vladimir Nabokov, and the script – a first in English for RWF as well as a first picture with a script not written by his own hand – came from the acclaimed British playwright Tom Stoppard. With Bogarde on board as well, it surely couldn’t fail.

“The script was almost an hour too long,” said the producer Peter Märthesheimer in Chaos As Usual. “We knew it would require a considerable amount of work. Tom Stoppard himself said he was sorry the script had gotten too long and that he wasn’t quite happy with this first version. But Fassbinder said, ‘No, it is an excellent script. I am going to shoot it kind of boulevard style, the dialogues in ping-pong rhythm, the whole thing at a very fast pace. I’ll cut some dialogue here and there.’ With that pronouncement, he relieved everybody of their responsibilities… Everybody thought he would eventually get this thing into reasonable narrative shape. I, however, felt it was already too late”.

Despair is a strange film indeed, and while it’s not perfect, there’s plenty to recommend it. As Fassbinder’s first English language film, it’s often the one Anglophones comes to first (either that or Querelle), but in many ways it’s his least typical. It’s more visually lavish than what we had hitherto been used to, with lush art deco mise-en-scène and clever camera work. What’s more, the motivation behind Hermann’s descent into madness and dastardly behavior is clearly signposted well enough, though the way he unravels is pure surreality, from him watching himself making love to his unfaithful wife Lydia (played delightfully by Andréa Ferréol) wearing an SS hat, to his single-minded machiavellian crime that makes no sense to the viewer. What’s more, Fassbinder seems to conjure up a sympathy for Hermann Hermann that Nabokov could never find for the character himself. “Hermann and Humbert [Humbert, the paedophile narrator from Lolita] are alike only in the sense that two dragons painted by the same artist at different periods of his life resemble each other,” Nabokov wrote from his Montreux home in 1965. “Both are neurotic scoundrels, yet there is a green lane in Paradise where Humbert is permitted to wander at dusk once a year; but Hell shall never parole Hermann.”

Resemblance is the key to Despair, or rather lack of it. Russian emigré and chocolate magnet Hermann is feeling the pressure as the fascists rise in the early 30s, and is thinking of ways of escaping the Weimar Republic. He hatches a plan when he meets his dopplegänger, a plot of fiendish cunning that involves murder and a sizable insurance policy. The only shortcoming in his strategy is that derelict Felix, his lookalike played by Klaus Löwitsch, actually looks nothing like him. Apparently Stoppard wanted the lead to play both parts, but Fassbinder insisted on his “double” being played by somebody else, a visual anomaly that puts a very different slant on the same script. One imagines the former way would have been more noirish, but under Fassbinder’s direction it’s an inscrutable and hypnagogic two hours. Despair is almost operatic in its ostentation and preposterousness (as part of the playful obfuscation, Fassbinder cast Armin Meier in three incidental roles). It’s funny too, in every sense of that word.

Humour was in short supply for a Nazi-themed film Bogarde made four years earlier. The Night Porter takes place in a hotel in Vienna, and features a sadomasochistic sexual relationship between an incognito former Nazi guard and an erstwhile captive of the concentration camp he presided over, played by Charlotte Rampling. Is it Stockholm Syndrome or something else that drives Lucia into the arms of her former captor, who she recognises while staying at the hotel with her American orchestral conductor husband? We’re given few clues as to why she’s drawn to her tormentor, and while many critics trashed it at the time, it’s a scenario that doesn’t seem completely infeasible given the perversity of human nature. Director and co-writer Liliana Cavani based it at least partly on a true story, though the soldier died at the end of the war, and each year the woman would fly to Germany on the same day to lay flowers at his graveside. Cavani decided to imagine what might happen had he survived after the war.

“The first part was fine, the middle a mess, the end a melodramatic mish-mash,” wrote Bogarde in An Orderly Man. “Too many characters, too much dialogue, two stories jumbled up together where only one was necessary, but the point was that in the midst of this tumult of pages and words, buried like a nut in chocolate, there was a simple, moving, and exceptionally unusual story; and I liked it.”

Many critics didn’t agree. Roger Ebert said it was “as nasty as it is lubricious, a despicable attempt to titillate us by exploiting memories of persecution and suffering”. Charges that the film was cheap Nazisploitation, a perverse trend in cinema at the time, were repudiated by Bogarde, who said he, Rampling, and Cavani never thought they “were making a porno movie” until producer Joe Levine “got hold of it. The point was, we thought – and I’d been to Belsen, I’d been to Dachau – that it was possible, in that hell and awfulness, that you could find one little seed of human compassion that would grow and form a plant of love. And it did happen. Not very many times, but I know that it did happen.”

With a similarly strange premise and with nods and winks to the erotic theatre of its predecessor, Despair is The Night Porter‘s younger, weirder nonidentical twin, a reflective prequel that takes the dreamlike quality of the former to its illogical conclusion. Like the SS officer, Hermann Hermann similarly ends up in a Viennese hotel assuming a disguise and on the run from his past. It’s the Night Porter back to front and upside down. Fassbinder would no doubt have been aware of the 1974 picture and it was likely his motivation for hiring Bogarde. Well that and The Damned from 1969, which he once listed as his favourite film of all time. Visconti’s picture is another sensationalist Nazi drama set in Weimar Germany paid for with Italian money, featuring a particularly brutal reenactment of the Night of the Long Knives. That film also starred Bogarde and Rampling strangely enough, making Despair the concluding part in an unofficial trilogy of disquieting Nazi stories starring Dirk Bogarde. While the war ended in 1945, clearly it never ended for Bogarde, and for Fassbinder it was just beginning.

Jeremy Allen is currently crowdfunding a book about Serge Gainsbourg. To support the project by buying an advance copy of the book, please check out his page on Unbound