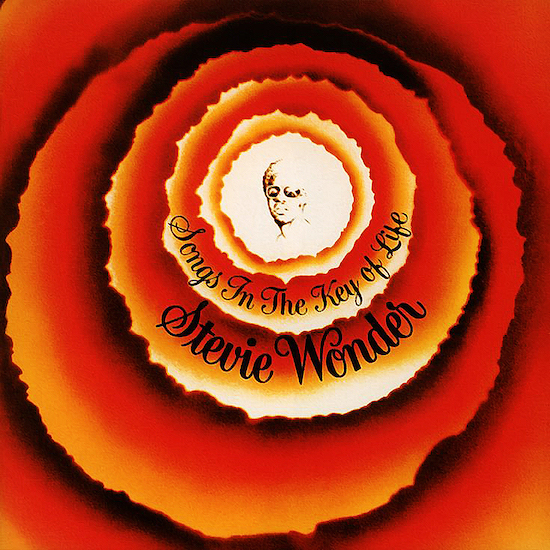

This Sunday, July 10, Stevie Wonder will perform his classic double album Songs In The Key Of Life in its entirety. Shameless nostalgia and actual storms notwithstanding, it is almost certain to be a stormer. Wonder has never lost his sheer, infectious, convulsive ability to entertain, to wrench every last, fat droplet of emotion out of any song he turns his voice to.

He’s 66 now – he was 26 when Songs In The Key Of Life was released, in 1976. At that point, he was absolutely on top of the world, the greatest soulman on earth whose magnificence overshadowed even rock and pop. Earlier that year, accepting a Best Album award at the Grammys for 1975’s Still Crazy After All These Years, Paul Simon thanked Stevie Wonder personally for not releasing an album that year.

Having made an initially awkward transition from his teen prodigy days with Motown, with the fitful, coming-of-age album Where I’m Coming From, Wonder then embarked on a series of albums throughout the early 70s which overlook the pop landscape like Rushmore – Music Of My Mind, Talking Book, Innervisions, Fulfillingness’s First Finale. These albums had the sort of universal outreach only The Beatles could match – from cruise liner MOR standards like ‘You Are The Sunshine Of My Life’ and wringing, emotive ballads like ‘You And I’ to lasciviously wrought, superbad funk outings like ‘Maybe Your Baby’ and ‘Boogie On Reggae Woman’, to canonical songwriting like ‘Superstition’ and ‘Higher Ground’, which will endure as long as there’s life on earth.

What’s more, these albums were composed from the most up-to-date fabric of modernity – the Arp and Moog synthesizers of Bob Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil. Wonder wasn’t the only pop and rock artist to use synths but only he among his popular peers had the patience to cope with their waywardness; born blind, he was more profoundly immersed in the soundworld they afforded, more curious as to their possibilities. The result was a newly established relationship between soul and synthesized sound in which he used the instruments not for novelty’s sake but to enhance the emotional range and warmth of his songs, as well as give them a more flexible physicality. These albums didn’t represent tentative, avant-garde experimentation; they were future-proof accomplishments which were immediately embraced.

By 1976, Stevie Wonder was the highest paid superstar in the world. During 1975, always heart-on-sleeve about his social conscience and disgusted by the behaviour of America’s Republican administration, the recently disgraced Nixon in particular, Wonder had openly contemplated quitting the music industry. He toyed with the idea of one last big farewell concert before relocating to Ghana and dedicating his life to charitable works. Wiping the sweat from their aghast brows, Motown’s executives persuaded Wonder that he would have better leverage in changing the world through his music than in working in a soup kitchen and, what’s more, slapped on the table a seven album, $37 million contract with complete artistic control. To rasping sighs of relief, Wonder accepted.

Anticipation for the album was immense, especially as it was put back, at Wonder’s insistence, from its original 1975 release date. Wonder was reputed to be sitting on a stockpile of some 250 songs from which he would make his final selection, his decision based on which way he thought current pop trends were drifting. Margouleff and Cecil were no longer part of the production team, with Wonder overseeing the album’s making alone. His blindness meant that he didn’t abide by the regular patterns and rhythms of everyday life, going long stretches without food or sleep, leaving studio co-workers flagging. He had a roster of guest musicians, however, ranging from Dorothy Ashby (who cut 1968’s soul instrumental milestone Afro-Harping) to Herbie Hancock, George Benson and Minnie Ripperton.

Songs In The Key Of Life is without doubt worthy to sit alongside its mountainous predecessors in Stevie Wonder’s formidable 70s pantheon. The unbridled, explosive, brass funk joy of ‘I Wish’, the violently happy obituary to Ellington that is ‘Sir Duke’, ‘Ordinary Pain’, a standard, self-pitying ballad which comes furiously to life when backing singer Shirley Brewer exercises her right to reply in the song’s so-sassy-it-hurts second half, ‘As’, on whose tidal, ocean waves of ecstatic jazz-funk a thousand subsequent careers were launched, notably that of Theo Parrish; ‘Another Star’, a Latin avalanche of pop joy which brings you to the verge of tears the way only Wonder can.

And yet, while others find in it astonishing range, a gamut of styles and emotions which saw both Prince and Elton John rate it as the greatest album ever made, it’s also an inconsistent, puzzling flawed album, not exactly an endorsement for the principle of total artistic control, and containing the seeds of his future staidness.

Never shy about being overly preachy on his albums, Wonder began with ‘Love’s In Need Of Love Today’, an anti-hate song drenched in gospel humming and synth strings, before swinging into the chippier, zippier Moog-flecked ‘Have A Talk With God’, crediting the Almighty with being the world’s “only free psychiatrist”, before swinging back, in contradictory, doleful mood to the mournful, synth-phonic strains of ‘Village Ghetto Land’, whose angrily despondent lyric surveys a terrain of desperate inner city poverty, of families living on dog food, which feels utterly Godforsaken. It’s hard to think of any one else who, like Wonder, can simultaneously harbour religious, affirmative elation and utter pessimism about the world in the same bosom.

‘Village Ghetto Land’ is one of the album’s best tracks, later reverentially simulated by George Michael. On side three, however, the album plunges to a nadir of mawkish, clumsy didacticism with ‘Black Man’, which anticipates the almost Sesame Street type fingerwagging of his infamous 1984 outing ‘Don’t Drive Drunk’. A paean to the multi-coloured races of the world and their contributions to humanity, it hears him deliver lines like “Farmworkers’ rights were lifted to new heights, by a brown man” in an agony of Wondersoul mannerisms that is hard to bear.

Worse, the track goes on an age, leaving the listener longing for a fadeout that never arrives, and before it does, inflicts a call and response section between teachers and schoolchildren in which they recite the names of multiple American pioneers. This is a recurring problem on the album – the endless modulations of ‘Summer Soft’, for instance, which sees Wonder ascend higher and higher through the registers with each superfluous chorus. Or ‘Isn’t She Lovely’, which makes its essential point about his daughter’s loveliness very early on, then rotates on the spindle for several needless minutes. If Wonder had so much material available, you wonder why these tracks spin out so long, or why he felt it necessary to add a supplementary EP of very ordinary Wonderfare, including ‘Easy Goin’ Evening (My Mama’s Call)’, a fireside instrumental harmonica workout.

Still, this was 1976, this was Stevie Wonder, this was Songs In The Key Of Life, and there was no reason to think he would only step up to even higher ground from here. And yet . . . that was pretty much it. Next up, two years later, was the largely instrumental album Secret Life Of The Plants, which made a good pitch for the affections of Prince Charles but otherwise baffled critics.

1980 saw a partial return to form with Hotter Than July, and the bountiful, bouncing ‘Master Blaster’, which optimistically heralded a bright future to come for newly free Zimbabwe. But thereafter? He attained even greater commercial success in the 1980s but on the back of more sporadic and distinctly weaker material; ‘Ebony And Ivory’, his facepalm duet with Paul McCartney which marked the decline of two towering artists into granny-friendly balladry long before their time and ‘I Just Called To Say I Love You’ are but two examples of how he’d cooled from black hot to tepid. ‘Happy Birthday’, meanwhile, calling for a National Holiday in honour of Martin Luther King. It’s as if Stevie Wonder himself had passed from innovator to national institution, answerable to nobody, retired from the responsibility of making decent records. Songs In The Key Of Life would turn out to be his last major stand.

What happened? Well, despite his groundbreaking use of synthesizers for textural purposes in the early to mid 70s, rhythmically he was somewhat hidebound, mostly working with a conventional drumkit, on which he was adept enough to play himself. By 1977, however, thanks to Giorgio Moroder and Kraftwerk, sequencers and electronic percussion were about to become the new drivers of funk and disco. Despite his use of sequencers on ‘Black Man’ and, on Secret Life Of The Planets, the brilliant, under-regarded ‘Race Babbling’, Wonder never really went disco as such, never got rhythmically down with the post-‘I Feel Love’ age. He preferred his slow singalongs. Even Songs In The Key Of Life’s up-tempo tunes, like ‘Contusion’ and ‘Sir Duke’ rely more on their surface energy then their percussive chassis. Ironically, he found himself eclipsed by electronics.

Suppose he had gone with the new electro flow? What might he have produced? A track like Soul Clap’s ‘Love Light’, an accelerated reworking of one of his better, later moments ‘Love Light In Flight’, gives a strong hint.

It seems like a waste of a once-prodigious talent; five years of brilliance followed by 40 years of . . . well, who remembers? But perhaps it doesn’t matter. Wonder’s legacy is huge in any case, one of colour and soul fabric which has gone on to inform the work of Prince, Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis, right through to contemporary R&B. For this alone, plus a voice that won’t quit, he remains among the very greatest solo stars on earth, thankfully still with us, one of the last living gods left. And Hyde Park will be an absolute stormer.

Stevie Wonder plays as part of Hyde Park’s BST series this Sunday, 10th July