All photos courtesy UP Center for Ethnomusicology

Maceda thought a lot about time. He once noted, on a flight from New Zealand to the Philippines, that the particular recording of a Chopin Berceuse being played through the tannoy “was so stiff that I wanted to jump out of the plane!” He knew what he didn’t want musical time to be: stiff, like that Chopin on the plane. And he had an inkling of what a more flexible approach to time might open up.

In a 1975 paper for the Third Asian Composers’ League Conference and Festival in Manila, he laid out his proposal for a reimagined sense of Asian musical time. This would not be measured by the clock, he explained, nor by barlines or time signatures, but through natural events such as the migration of birds and the flowering of plants. Accordingly, his own music plays tricks on regulated time. It moves at a pace that refuses to be either steady or erratic – somehow it is both and more, an eddying equilibrium, a fluidity that gives the impression of being totally loose and organic. I say ‘impression’, because in fact his seemingly elemental flux is meticulously constructed.

Maceda thought a lot about drones. By ‘drone’ he did not mean a monotonous repeated note or single long sound. His drones are more coruscating than static, made of hundreds or thousands of enmeshed individual parts, and the overall effect is a shifting continuum. Imagine a shoal of fish. That’s the iridescent constant he was getting at.

Maceda thought a lot about opposites, and how they seemed to him to be a Western obsession. In an essay called A Concept of Time in a Music of Southeast Asia, he references Jacques Derrida on the subject:

Good vs. evil, being vs. nothingness, presence vs. absence, truth vs. error, identity vs. difference, mind vs. matter, man vs. woman, soul vs. body, life vs. death, nature vs. culture, and equal entities. The second term in each pair is considered a negative, corrupt, undesirable version of the first. In other words, the two terms are not simply opposed in their meanings, but are arranged in hierarchical order which gives the first term priority.

Add to that list: tonic versus dominant, the linchpin relationship around which tonal harmony pivots. (Take the key of C major: C is tonic, G is dominant.) Maceda believed that Western tonal music is dominated by an obsession with closure – and that although such an obsession might give comfort and seem to solve problems simply, he considered it a “narrow view” that “may lose its contact with other perspectives, especially a concept of the larger space, infinity, a metaphysical construct of the universe”. He lamented that “there is less room for qualities like patience, sorrow, doubt and humility, and other spiritual attributes which are spurned by the righteousness of logic and precision”. Maceda, like Nan Shepherd, sought to be unmade.

He knew full well about the many movements that were concurrently trying to break down the post-Aristotelian dualism that had been at the heart of Western classical music for centuries. Movements including atonalism, total serialism, musique concrète, aleatoricism, modal jazz, free improv, minimalism and more. But his particular way of prising open the tonic/dominant supremacy was to build an alternative based on Asian foundations. He favoured the egalitarianism of the five-note pentatonic scale (imagine playing only the black notes on a piano), which he felt gave every note equal importance. He was also increasingly interested in mass participation as a way of dodging hierarchy in performance. He began writing works in which every voice and limb contributed to the whole.

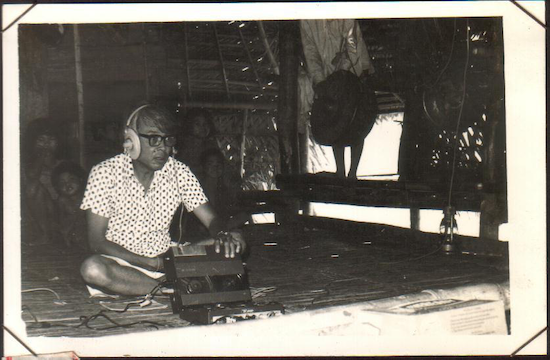

In 1971, Maceda made a piece for a hundred cassette tapes. A hundred performers with a hundred portable tape players infiltrated the lobby of the Cultural Center of the Philippines. He called the piece Cassettes 100, and the tapes played recordings of indigenous instruments and natural sounds, together making a happy heap of field material and musique concrète. “The recordings are my dictionary,” he explained. “They are a receptacle of ideas from which I can pull at any time.” As the participants moved their bodies in slow choreographed gestures, brandishing tape players in their outstretched arms, the sounds swirled accordingly. Cassettes 100 was the first time Maceda brought the village to the heart of the city, and the first time he braved a large-scale performance happening. Three years later, he would repeat the act in Ugnayan, this time involving millions.

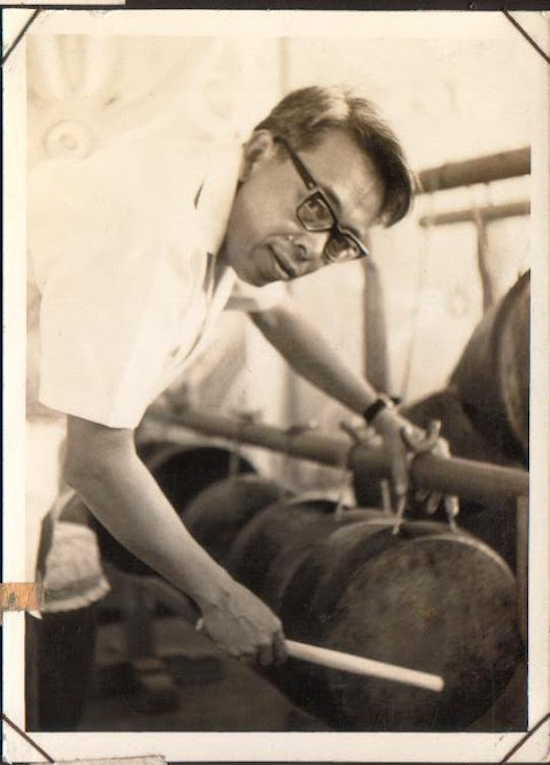

Ugnayan begins with forty kolitongs (zithers), all playing tiny melodies, all tuned slightly apart. Beaters patter off strings like rain on a tin roof, insects flitting against lightbulbs. There is no measurable pulse, no regular beat. Then in come the hectic balingbings (rasping bamboo buzzers) and the low, docile bungbungs (bamboo flutes that sound like slow-moving herbivores). The rain gets heavier then eases off; bangibangs (yoked-shaped wooden bars that are struck with beaters) join the party, all at their own pace. The bungbungs layer up; the kolitongs whip themselves into a frenzy then fix on single pitches. A new voice arrives: the ongiyong whistles, short, sharp, shrill. An exquisite dance ensues, circling between buzzers, gongs and Chinese cymbals. And then – thirty-seven minutes into this amassed percussive ritual – human voices! Emerging from all directions, intoning a single syllable: YAA! All on the same pitch at first, then they move ever so slightly apart, and there is a narcotic sensation of being in the thick of this incantation, that the music is swirlingly multi-dimensional. The vocalists murmur then open their mouths, dazed, ecstatic, elastic. Cymbals crash, gongs gong, kolitongs flicker then fade into breath. The ongiyong whistle flutes have the last word, and then it’s all over, cloudburst cleared as suddenly as it began.

The early decades of independence had been a bumpy ride for the Philippines. On the back of rising crime and regional unrest, a botched assassination attempt on a key government figure (possibly staged by the government) and the potential of a communist uprising backed by China, President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law on 21 September 1972. He slashed press freedoms, opposition politics and the powers of congress. Protesters were exiled or just plain murdered; poverty soared and human rights were trashed while Marcos and his wife stole billions in public money to collect gold kilobars and, infamously, a lot of shoes.

As well as designer footwear, Imelda Marcos had a taste for lavish cultural and infrastructure projects. She went in for exorbitant, staunchly brutalist architecture like the snaking San Juanico Bridge (a birthday present from Ferdinand in 1973) and the breathtakingly austere pyramid bunker of the National Arts Center. These projects and others earned her dubious notoriety for having an “edifice complex”, but it was not just buildings she indulged in. The vast scale of Maceda’s Ugnayan was possible only thanks to the First Lady’s personal support.

“They used me,” said Maceda. “They changed the word. Ugnayan. It means ‘working together’.” Initially, Maceda had a different name in mind. He originally wanted to call it Atmospheres – for him, the thrill of the ginormousness mainly had to do with the amassed multi-textured sounds made possible by the sheer number of participants. But he had to acknowledge that “there was a political side to it. I agreed to it just so I could do the project. One letter from Mrs Marcos to all the radio stations and, well, I got what I wanted. At least in theory.” Promotional blurbs that appeared in newspapers and pamphlets in the lead-up to the premiere explicitly aligned Maceda’s work with the regime’s agenda. Here is one such advert:

As a creative ideology for unity and community . . . Ugnayan can operate in large or small groups . . . brought together or linked together for positive ends. It would be difficult for this nation to develop its full potentials, to experience its longed-for democratic revolution . . . in the generation of a new reform-oriented and a compassionate development-oriented society, unless its people are one in body and in spirit.

The Marcos regime aimed to foster an image of collective harmony, and to cast Manila’s cultural elite as a central civilising force in its prosperous new society. “For the regime, it was convenient to have someone like Maceda around,” says de la Peña. “Someone who was respected internationally and who kind of paralleled their agenda.” De la Peña was still a child in 1974 but he remembers the hype and the literal noise around the event. “Martial law – it was a bit like lockdown now,” he tells me during the coronavirus pandemic, “but even worse. New Year’s Eve in Manila is usually very loud. For the first time in 1972–3 it had been silent because of martial law. Then came 1973–4, only the second time we had New Year’s under martial law. And they staged this piece. It was packaged for us as the new way of merry-making. Like: who needs fireworks when you’ve got Ugnayan!”

How should we understand the symbolism of Ugnayan now? As a musical experience, it was surely designed to incite collective attentiveness, collaboration and zen. The year of the premiere, 1974, Maceda spelled out what he saw as the positive ideological overtones, writing that “the idea that only large groups of people can put together sounds spread out over a big area is paralleled by the co-operation necessary for large numbers of people to achieve a certain purpose”. In his history of Filipino noise music, the musician Cedrik Fermont hints that, for him, Maceda’s political collusion taints the spirit of Ugnayan. For him, despite Maceda’s claims to transcend nationalism, the composer’s “emphasis on the identity and the history of the Filipino people felt well under the appreciation of the President’s views of national values”.

Dayang Yraola is more equivocal, explaining that these are still sticky subjects among Filipino academics and musicians. “The Marcos regime, as you know, is a whole murky story on its own,” she explains to me, and proceeds to give a précis of what happens when a political history is oversimplified and a national artist is lionised beyond scrutiny. “People have been avoiding this for a long time,” she emails. “At present, when many are against all of the Marcos legacy (regardless of its actual effect on the nation), how would you reconcile the association of rare talent such as Maceda, who is now considered pride of the nation? Enemy of the Nation + Talent = Pride of the Nation.” She concludes: “This is not actually a viable equation.”

Sound Within Sound: Opening Our Ears to the Twentieth Century by Kate Molleson is published by Faber