“First, I systematically tried all 1,000 combinations of the lock,” Holly Herndon tells me, referring to her suitcase mishap upon arriving in London a couple of days before our conversation, amusingly recounting a member of hotel staff opening the lock in seconds, only after she had entered every possible three-digit combination. We are meeting to discuss her second full-length album proper, Platform, and her first with 4AD, having previously worked alongside Brooklyn-based RVNG INTL – the record is a shared release between the two, Herndon keen to build relationships. “A lot of artists might start out on a smaller, more independent label and then say ‘see you later’, but that’s not how I like to work,” she says. She views this move as a chance to extend her reach and that of Platform as just that, a platform.

Assembling an extensive team of collaborators, Herndon presents Platform as both a vehicle for her and a number of creatives, whose works and theories she has heavily invested her time and work in, to ask questions, politically and socially. Embracing the concept of ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response), the pleasurable tingling sensation that may arise in response to certain stimuli, ‘Lonely At The Top’ questions the motivations of the financially and socially privileged, the narration of Berlin-based ASMR-tist Claire Tolan plunging the listener into the sterile climes of a spa treatment as she repeatedly assures her unheard client “you really deserve it, you work so hard.” Working alongside duo Amnesia Scanner, as well as theorist Suhail Malik, on ‘An Exit’, Herndon poses that “when there is nothing to gain, there is nothing to lose.” Artist Spencer Longo (who operates under the @chinesewifi Twitter account) wrote the text for ‘Locker Leak’, which sees Herndon reeling off self-help quotes and various spoken word iterations (“Be the first of your friends to like Greek Yogurt this summer”, “Add it to your Bucket List”), products of an industry that increasingly disguises self-gain and profit in ethical marketing campaigns around self-improvement, mentally and physically.

The album’s title itself derives from strategist Benedict Singleton’s platform dynamics theory, which, as Singleton outlines here, presents a collective effort “to get out of the present, not lock down the future.” As Herndon tells me, Platform is an opportunity for not just her but “other people to communicate and share ideas” too, and bringing together this cast of minds is therefore a natural move to take. “If I’m talking about us as a society and communicating collaboratively, the first step to doing that should be through my own practice.”

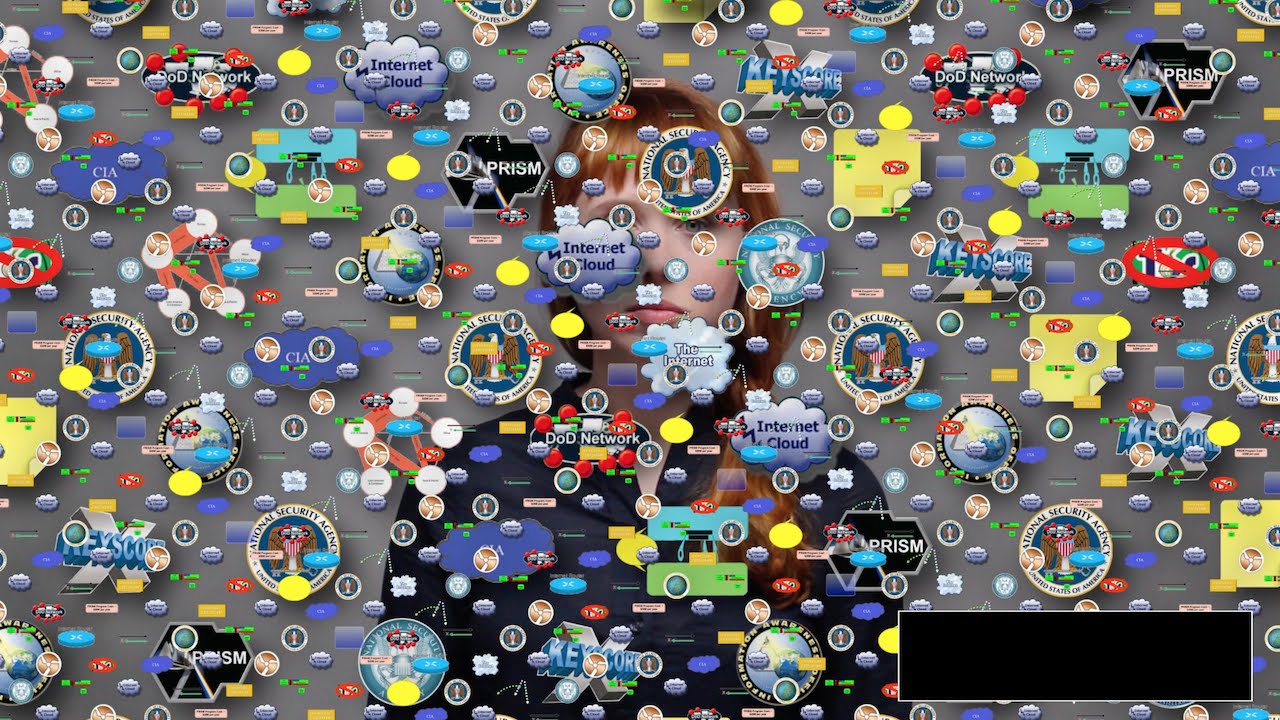

Talk of conceptual theory can often garner accusations of pretension and disconnection, a problem that Herndon says she faced in the critical response to 2012’s Movement, but, importantly, Platform also sees Herndon bathing every concept in arresting, silky melodies, created with the level of detail that those familiar with her work have come to expect. Choral harmonies figure throughout, the somewhat angelic vocal of collaborator Colin Self forming a particularly striking accompaniment to Herndon’s manipulations on ‘Unequal’. “We have to believe that we can actually make it better,” she tells me. With Platform, Herndon is offering an opportunity to address particular problems – inequality and government surveillance (on the NSA-based ‘Home’) to take two examples – and, above all, thanks to the coming together of her collaborators and their theories, as well as the backgrounds from which those ideas have been sourced, offering an optimistic channel by which people can put forward solutions, collectively, via the platform that she has.

Taking the idea that you often put forward of your laptop as a central instrument, there’s a pervasive view often presented by a certain old guard of media that we apparently don’t have real, face-to-face conversations anymore, and that technology is harming real life interaction. Do you think, through your work, and what you produce using technology, you’re pushing against that idea somewhat?

Holly Herndon: I think our society likes to talk about technology in really black and white terms, so things are simply defined as positive or negative. That doesn’t solve any problems and I think it can be anti-intellectual. So with my work, I like to ‘complexify’ issues a little bit and show that certain concepts are not just simply good or bad. With a track like ‘Home’ it’s obviously very critical of the NSA and aspects of technology in my life and people have been like, ‘So, does that mean you don’t like your laptop anymore?’ My response is always, ‘No, that’s not what that means.’ It means that I can still have a love and appreciation of that as a tool but you can always still be critical of it.

Following on from ‘Home’ and its subject matter of the NSA revelations, do you think that confirmation that governments were snooping on us affected your work on the rest of Platform?

HH: I think it seeped in in very subtle ways because I was using Mat [Dryhurst’s] ‘net-concrete’ concepts, but also taking parts of field recordings that I had gathered from all kinds of different places. I had never really done that before in terms of using field recordings, so I started integrating various domestic sounds a little more. So that idea of everything being public started to push through in a very subtle way.

When it comes to sampling and going through all of the recordings you collect via your use of ‘net-concrete’, do you find it can be a laborious process in terms of picking out what is suitable for use?

HH: It can be. I think that, sometimes, one of the hardest things can be just getting started on actually making a project, so I like having a process that will generate those beginnings, that you can listen through, audition it and decide what works and how it will work. So yes, sometimes, there are just volumes of samples to work through and filter out sounds, but that is one of the parts I most like doing in a studio. It’s very cathartic to listen through it all and hit upon something and say, ‘Oh, that.’

So it’s not tedious in any way to you?

HH: It’s super tedious, but I think most electronic musicians enjoy some level of tedium [laughs].

Do you think you could identify a particular reason for that?

HH: I think it’s that level of catharsis in a studio. It’s one of those ‘love-hate’ concepts, the detail work, the moving of the hit a couple of milliseconds forward and then listening to that loop over and over – it’s part of producing.

Having read a lot of interviews with you in the past, a general focus tends to be mostly on the technological aspect of your work. Do you feel that there’s a more personal level that you would like to be discussed in more detail?

HH: For this album?

I think generally, including CAR and Movement as well, for example.

HH: I think that’s actually a shift that has been happening more with this album. I think it’s more overtly ‘emotional’. That’s one criticism that people had towards Movement, that it was apparently so technically precise that it had no soul or something, which was really funny because that was actually a really personal record and had a lot of ‘soul’ or whatever.

The music industry tends to work with nostalgia and archetypes, especially in terms of emotionality. We’re supposed to understand that this certain vocal inflection means I’m really feeling it right now. For me, I know that is designed to trigger that, so it’s not a particularly emotional concept for me to take on because it’s not actually coming from anywhere – it seems to be more lifted from somewhere else culturally. So I’m trying to find what emotionality is with these tools and also what I can gain from various online relationships. For new relationships and a new paradigm that we’re living under in 2015, we need new modes of expression, so I try not to rely on established or traditional ideas. People who might be used to that seem to read into it as me not being personal or expressive when there’s actually a lot of that in there.

Would you say, speaking rather generally, too many people are still set, both musically and technologically, in certain ideas of orthodoxy?

HH: In music, I think so, definitely. Music can be quite conservative and then in club environments, there are so many references of orthodoxy that we can speak about in the club. One example is when it comes to the tools that you use and the looking down upon of laptops, so it’s considered authentic to use old-school forms of hardware, but it’s also expensive to do that. An original 808 is thousands of pounds and I don’t like the idea of authenticity having a price tag like that. I think that’s fucked up.

And it also, of course, makes music production and sharing the reserve of the privileged.

HH: Sure, as if that wasn’t the case already. That makes it even more dangerous, so I don’t like authenticity being tied to how we present music. That word ‘authenticity’, I wonder what it even means anymore. I feel quite uncomfortable saying it, but people often try to tie it into concepts like that.

Reading a recent interview where you referred to your religious upbringing in Tennessee, you said that it’s deeply personal to you and hard to talk about for that reason. How are you drawing out what’s personal to you on Platform in terms of your own experiences?

HH: I think it’s a very personal record. Religion and spirituality isn’t a particularly large part of my life. It’s such a weighted topic for some people but it’s not something I spend a lot of my time thinking about. It comes down to me feeling that I don’t really have anything to add to that conversation so I try not to delve into it. My parents are extremely religious and I was raised going to church about three times a week. That was one of the questions I was asked at the RBMA talk about whether I was spiritual and I was like, ‘Argh, why did you ask that?’ [Laughs] For some reason, it’s just not something I like to go into, not that I’m trying to hide anything.

Talking about Platform then, where and how do you think those personal elements are drawn out sonically?

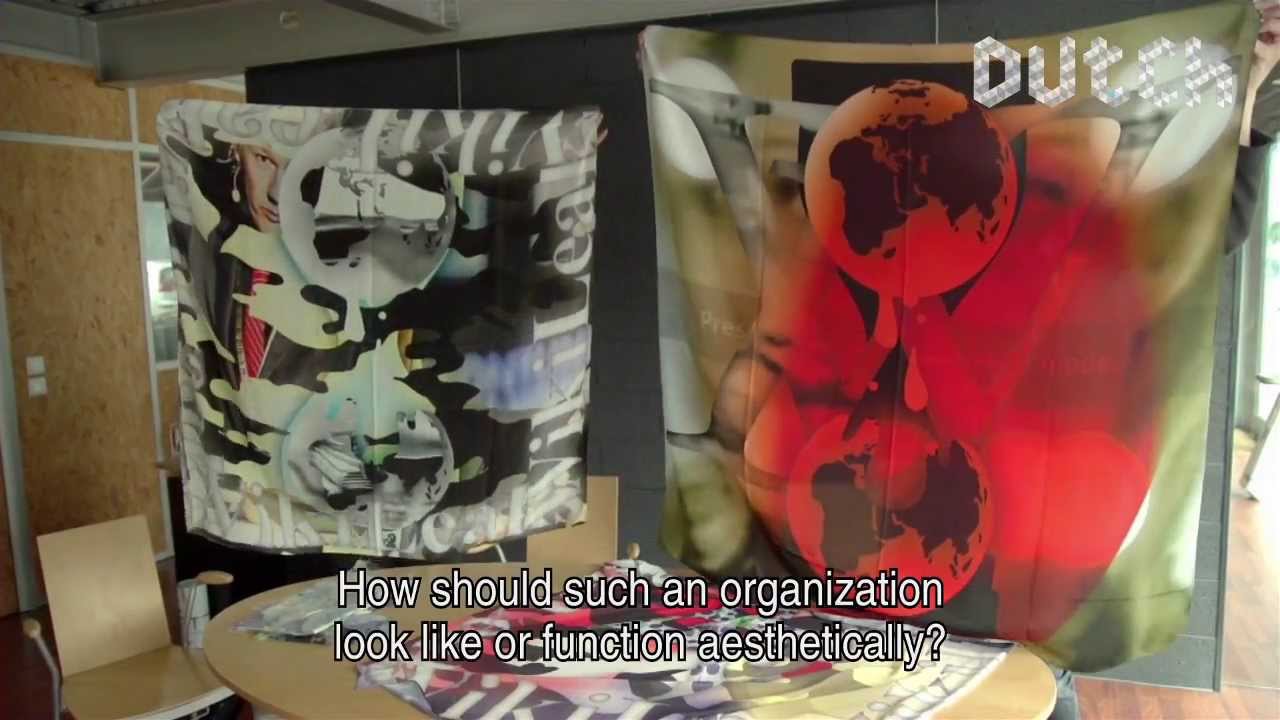

HH: Those domestic sounds I incorporated across the album and my work with Metahaven too. They often use the slogan that ‘the personal is the political’ which is a term that I really like, so I tried to include a lot of personal sounds with that in mind. There’s also a part from recorded Skype conversations between myself and my partner Mat where I’m laughing really hard and sound like a weird animal, so I used that in a song. There are a few really personal and domestic moments like that, but they’re not necessarily overtly like, ‘Here’s a private conversation between myself and my partner.’ It doesn’t have to hit people over the head. I feel like the whole palette is hyper-personal and made from my browsing, the sounds around me, my body and those of my collaborators.

There’s very little actual synthesis, so there are some synthesisers and drum machines, but it’s mostly really personal sounds. The content as well, like ‘Morning Sun’ is a love song. The lyrics are about having to leave my partner all the time and go on tour and I just sat down and wrote that in about five minutes without even intending to make it to be released. I played it to Mat and he was like, ‘No, this is a great song’ and at first, my reaction was, ‘No, this is so silly’ [laughs].

Listening to Platform, I guess ‘Morning Sun’ is one of the moments that would be picked out as most accessible or ‘pop’ to take a broad term, but do you find putting those kinds of descriptors on art can be problematic regarding the possibility of restricting how we think about and enjoy music?

HH: It can be, and I think it’s something that’s heavily tied in with the economics of the music industry which I’m sure will all dramatically change soon, like we’re all into wax, which seems insane.

The physical format is something that you addressed, of course, in your RBMA talk in Tokyo, regarding the loss of instancy.

HH: It always pisses people off where they’ll say, ‘What? You don’t collect vinyl?’ I move around a lot, so it makes no sense. The whole process of sharing music, the physical format makes it a lot longer. I finished the record in September and we’re talking about it now. Television, for example, is so much more instant, where something might happen politically and then South Park will have a cartoon addressing it the next week, so it’s immediate and fresh in people’s minds. It’s sometimes frustrating to have to wait so long for people to hear something. You can be immediate if you put it on Soundcloud or whatever, but then the media doesn’t take it as seriously. Everything seems to revolve around the physicality.

There’s always a constant drive as well for what people horribly refer to as ‘content’.

HH: Yeah, it all has value to people in different ways. It holds value to the media outlets that are trying to sell clicks and advertising with their banners. Then there’s the value to the ‘consumers’ which is a horrible term that people use to refer to fans who are enjoying what you produce, and enjoy it for a lot longer than the one day it’s on the cover of whatever magazine. That’s what matters more. I still have people that will tweet me about how they just listened to a track from Movement and say it made them feel a certain way, so people are always discovering things.

In terms of releasing though, I’d love to have a way to finish something, have it mastered and then not have to wait eight months because it’s just a very long time. One of the most interesting things about vinyl is that the most profitable releases are generally reissues which is quite depressing and comes at the expense of supporting new, young artists. There’ll be a Led Zeppelin reissue, but Robert Plant’s fine. He doesn’t need anymore of that kind of support.

Coming back to your work with Metahaven and that slogan of ‘the personal is the political’, I spoke to Jam City recently about similar ideas based around optimism and I noticed you commented on his work, via Twitter, saying that, ‘The most important thing you can do in 2015 is believe in something.’ I found that very interesting and, personally, wonder whether cynicism is getting in the way of active change. Do you think we’re a generation that’s too caught up in cynicism?

HH: Cynicism, sarcasm and mockery are the main ways in which we seem to deal with the shit storm that has been delivered to us, economically and politically speaking. In the US, socially speaking, there are obviously huge racial issues being addressed, particularly around police behaviour. It’s tough to see, culturally, the response be so cynical. It doesn’t particularly solve anything to be cynical. It doesn’t change a situation to just mock it, so if we want situations to be better, we have to learn how to communicate better. We have to believe that we can actually make it better. Also, I think it’s part of our responsibility as artists to present what we want that future to look like. We can’t just say ‘this sucks, I don’t like this’. What is your dream? What do you want? Be creative because that’s why you do what you do.

It’s the same with technology where it’s so much easier to just criticise it in a very simple way, but to actually deal with the situation and isolate what is good or bad is more positive. People should take their role seriously as being able to present new ideas or champion other people with those ideas. I think what Jam City’s doing is awesome, because it’s finally someone actively speaking out rather than some mysterious, brooding guy being all shadowy. I think that offers a new paradigm or archetype for other people to step out like that and for their fans to take on these ideas too and be positive.

How are you looking at incorporating Platform into live settings?

HH: That’s something that’s quite TBA right now. I have to grow it incrementally but what I would like to do, scaling it according to the venue, is use Platform as a platform, in some instances, for other people, that were involved in the record or inspired the record, to share their work and their ideas. We’re experimenting with that here and there, so we’re going to be performing with Metahaven, for example, in Berlin, as well as Amnesia Scanner and Claire [Tolan]. I like the idea of inviting theorists to do something at a show as well, like Suhail [Malik] who is a regular reference point for me, but it’s just figuring out how to make that work and not be didactic.

Do you try to be specific about what kinds of live environments you play in?

HH: To an extent. If you get too picky, then you start to restrict yourself on where you play and who you reach. I like to be flexible and use different venues in different ways. I haven’t played many outdoor festivals, so that could be a new, interesting thing for me to take on.

Recalling your show at Wysing Arts Centre last year where you were backed by visuals displaying social media profiles of different people in the audience, was there an element to that project of trying to make people feel uncomfortable?

HH: [Laughs] Everything has been thought out of course. We wanted to flip the dynamic and make the audience part of the show, but also, like ‘Home’, show how much personal information is on public display. Mat was really careful to not click on an embarrassing shot of somebody, so it’s definitely not about making people feel shitty, but rather just thinking about how accessible we are online, post-NSA. Mat does a lot or work around artists’ rights and privacy in his own practice and he recently released some software called SAGA and it’s a continuation of that theme.

Focusing on some specific tracks on Platform, I was quite intrigued by some of the spoken world elements on tracks like ‘Locker Leak’ and ‘Lonely At The Top’. Taking the latter particularly, what was the idea behind that track?

HH: ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response) is a really interesting community that I was drawn to because, like we were saying before, there are so many over-simplified viewpoints on technology and people saying that we aren’t connecting anymore, but with ASMR, there are these strangers online connecting through YouTube videos acting as a nice counterpoint to those simplistic arguments. I met an ASMR-tist, Claire [Tolan], in Berlin, who has a radio show there [on Berlin Community Radio], and I really wanted to work with her. She recorded it, we wrote the text together and then we edited it together too. ASMR is quite therapeutic – I’m really sensitive to acrylic fingernails on smartphones – and you can watch various YouTube videos which will help you to identify something that you might be sensitive to. Since it’s quite therapeutic, we thought it would be funny to flick the switch a little and write something critical about the ‘1%’ and how, if you’re a very wealthy person, you might feel that you really deserve these good feelings like they’re a birthright. There was an article I read about the theory of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ where there is a psychological term for wealthy people believing this because you kind of have to convince yourself in order to believe you should have something. It’s often people in that kind of position that can make changes towards the system, so they have to convince themselves it makes sense. Otherwise, they should do something about it because they’re in a position to, so that was our dig against those people.

One of the most interesting aspects for me is how you only hear that one person’s voice and not the voice of the wealthy person being spoken to.

HH: That was really difficult to write and record because we were describing a person that you never hear. That was a fun challenge and Claire is awesome. She works for an NGO in Berlin that’s called Tactical Tech where they help educate people on privacy issues, and she’s also working to build an archive for content that is too difficult for YouTube but captures war crimes. It would be taken down from YouTube because it’s too graphic so she’s helping to build an archive for that material so it can be retraced and people responsible for crimes can be traced. Working with people who have such multi-faceted skills and ideas is really important to me.

Honing in on the technique of ‘Musique Concrète’, and how seminal it is to your work, what do you appreciate about that form of production?

H: That’s something that came out of my use of sampling and Mat’s ‘net concrete’ system which is very much related in terms of jamming sounds together, while also wanting to bring in the sounds of my environment more, including the messiness. I really like that messiness you can get with sampling. It sounds more earthy and I appreciate the idea around DIY technology and the aesthetics around that. I think when people imagine the future, they seem to imagine this sterilised lifestyle, but I don’t think nature or dirt and that messy imperfection has to go away.

Platform is out now, via 4AD and RVNG INTL. Holly Herndon plays London’s XOYO on June 10 and Birmingham’s Supersonic Festival on June 12