V masks modelled by occult Scottish noise rock group Black Sun

It happened again the other day. This time the unmistakeable mask flying across the internet and newspaper front pages was associated with the Occupy movement and, for some at least, November 11 was morphing into V Day this year. Earlier in the year, as Egyptian protestors occupied Tahir Square and tried to overthrow the Mubarak regime, images circulated showing the Sphinx with a familiar moustache and smile.

The face is that of V, the anarchist terrorist at the heart of Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s classic comic book V For Vendetta and the mask of choice for 21st Century protestors from the Anonymous hackers to students protesting against higher tuition fees.

Dressed in the Parliament-bombing finery of one Guy Fawkes, V is the mysterious protagonist set on destroying the fascistic Norsefire regime installed in Moore and Lloyd’s dystopian England after a nuclear conflict has laid waste to much of the world.

Starting in 1981, Moore and Lloyd extrapolated a beautifully realised nightmare. The extreme right wing regime of Adam Susan (renamed Sutler in the film which Moore famously hates but Lloyd likes) rules over a grey unhappy country kept in line by a police state armed with the Eye, the Ear, the Nose and the Finger. At the centre of it all is the Voice Of Fate – a supercomputer personified by an actor – who broadcasts the regime’s propaganda; ending each message with “England Prevails”.

The V mask seems to have been first worn regularly in a protest by members of the online community Anonymous, who pitched up outside Church of Scientology centres in January and February of 2008. Anonymous – whose no leaders philosophy V would surely have approved of – were out to expose the heavy handed nature of Scientology after the new age cult tried to get a Tom Cruise interview effectively removed from the web.

Anon, by Ewan Alnak

Anonymous, who, among other protests against control of the web, were also involved in internet attacks on companies who denied services to Wikileaks, are believed to have been inspired by Epic Fail Guy rather than V directly. Epic Fail Guy first appeared on the 4Chan message boards from which Anonymous grew in 2006 and when he picked a V mask from out of a dustbin and stuck it on he gave Anonymous members a convenient protest shorthand for their actions in what they call “meatspace”. So, bizarrely, it seems that the V mask started its journey into protest land as a dig at the film – if Epic Fail Guy does something, it’s bad.

Since then, the mask has gone global and spilled across the political spectrum. This November 5, visitors to London’s tourist hotspots could see libertarians organised by the Bastard Old Holborn blog marching on Parliament in V masks carrying banners proclaiming “Cut deeper. Taxes = slavery” before popping down to St Paul’s to see the Occupy LSX campers in their masks discussing how to rein in global finance.

Bastard Old Holborn would, I suspect, have little time for Alan Moore, and, like Paul Staines of the Guido Fawkes blog is more likely to be channelling the original Gunpowder Plotter (“the last man to enter parliament with honourable intentions”) than the anarchist V. Whereas those newspaper commentators who get huffy at the sinister implications of anarchists in Guy Fawkes masks are probably missing the point of those protestors.

To some then, the face is that of a 17th Century Catholic ultra-monarchist terrorist, to others a fictional anarchist freedom fighter.

The marriage of Lukas and Josie Best, 5 November 2011, West Australia

The film of the book, with its stirring final scenes showing an army of Vs marching to victory, has been a fixture on British terrestrial television for years now, and has – as Lloyd himself admits – had a greater impact than the book. It’s been reported that the mask is now the biggest selling on Amazon. Of course, there are those who complain – truthfully – that everyone who buys one of these masks, gives some money to Time Warner. There is a vague symbolic point here but it is also one of those facts whose significance wanes the more you think about it. Compared to the control structures and the amount of money the 99% are protesting about, an extra few thousand pounds going to Time Warner represents merely a starling’s tear dripping into the Atlantic Ocean. Really it is the standard right wing complaint brought to bear in such situations (see also: Naomi Klein’s No Logo still makes sense even though she drank a Starbuck’s Skinny Mocha Latte once in 1997 and Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent hasn’t been fatally injured by the fact that he watched The Simpsons occasionally). Such complaints are fatuous when you’d have equal right to attack protesters over where they eat, buy clothes from, pay rent to and work in day jobs. They are probably aware that they are trapped in the machinery of late capitalism. This is, after all, what they are protesting about.

Lloyd continues to work successfully as an artist and now writer. We asked how he helped create V, and what it feels like to see your art become a global symbol.

Occupy Wall St at Zucotti Park, October 15, by Chris Bickel

I understand it was your idea to base V’s look on Guy Fawkes but you couldn’t find an actual mask on which to base the V face. How did you design it – did childhood memories of bonfire Guys come into it as well as the real Guido’s pointy beard?

David Lloyd: Well, we created V in the summer and there were no actual Guy Fawkes masks to be had from the stores at that time. I contacted costumiers, theatrical suppliers, etc, but couldn’t get one at those places, either. The idea was to actually use the kind of papier-mâché mask we put on the dummies. In the event, I had to invent one from my memory of them, which led to the famous smile – it was an accidental addition caused by my mental impression of what the mask looked like. But it was probably my memory of the shape of the moustache that led to it. At any rate, it was serendipitous.

He has quite a friendly face with those bulging, smiling cheeks, was that important to the concept of V?

DL: The accidental smile gave us all that ‘smile on the face of the tiger’ resonance, and ‘smiling in the face of adversity’, etc. And it reflected the nature of one of the two inspirations behind the series – a project of Alan’s about a terrorist in white face make-up. The mask and look became very useful all round as a dramatic device.

Comic book artists do sometimes see their art come to life in action figures and other merchandise as well as on film but surely you can’t have imagined that the V face would extrude into real life – and real political life – in the way that it has?

DL: I can’t say I did. Though I was always aware of its power as an image, and the impression it made on people.

Graham, by Hannah Woods

How do you feel when you see a V mask or the V graffito at a protest or on a blog?

DL: Happy that a symbol of resistance to tyranny in fiction is being used as a symbol of resistance to any perceived tyranny in real life. The image of Che Guevara – another bearded guerrilla fighter, though in reality – has been used similarly as a badge of resistance to perceived injustices, and V’s just joined the club. Badges and symbols are useful as instant communication devices, though in the case of V, it seems to me that the communication isn’t quite as instant as with figures such as Che because, despite the movie, V For Vendetta, and its trappings, is not well-known to the general public. But then, any puzzlement shown by anyone in ignorance can always be allayed by their investigations of the source of the images – and then, who knows, they might become beneficially educated by the experience!

V’s an anarchist, but I see you and Alan coming from a left anarchist perspective while the V face has been used by right libertarians too, does this bother you at all?

DL: Don’t see a left or right stance in anarchist principles, myself. Anarchy has its own position as far as I see it. But the uses the images of V have been put to vary according to the tyranny that is perceived. I’ve seen an image of V used in a very right-wing context in which the tyranny is perceived to be from Islamic fundamentalism. A creator loses control of his work as soon as he releases it to the world, and he can only hope that, if it’s used, it will be used to the good – if that’s what was intended – and not to what he thinks is the bad.

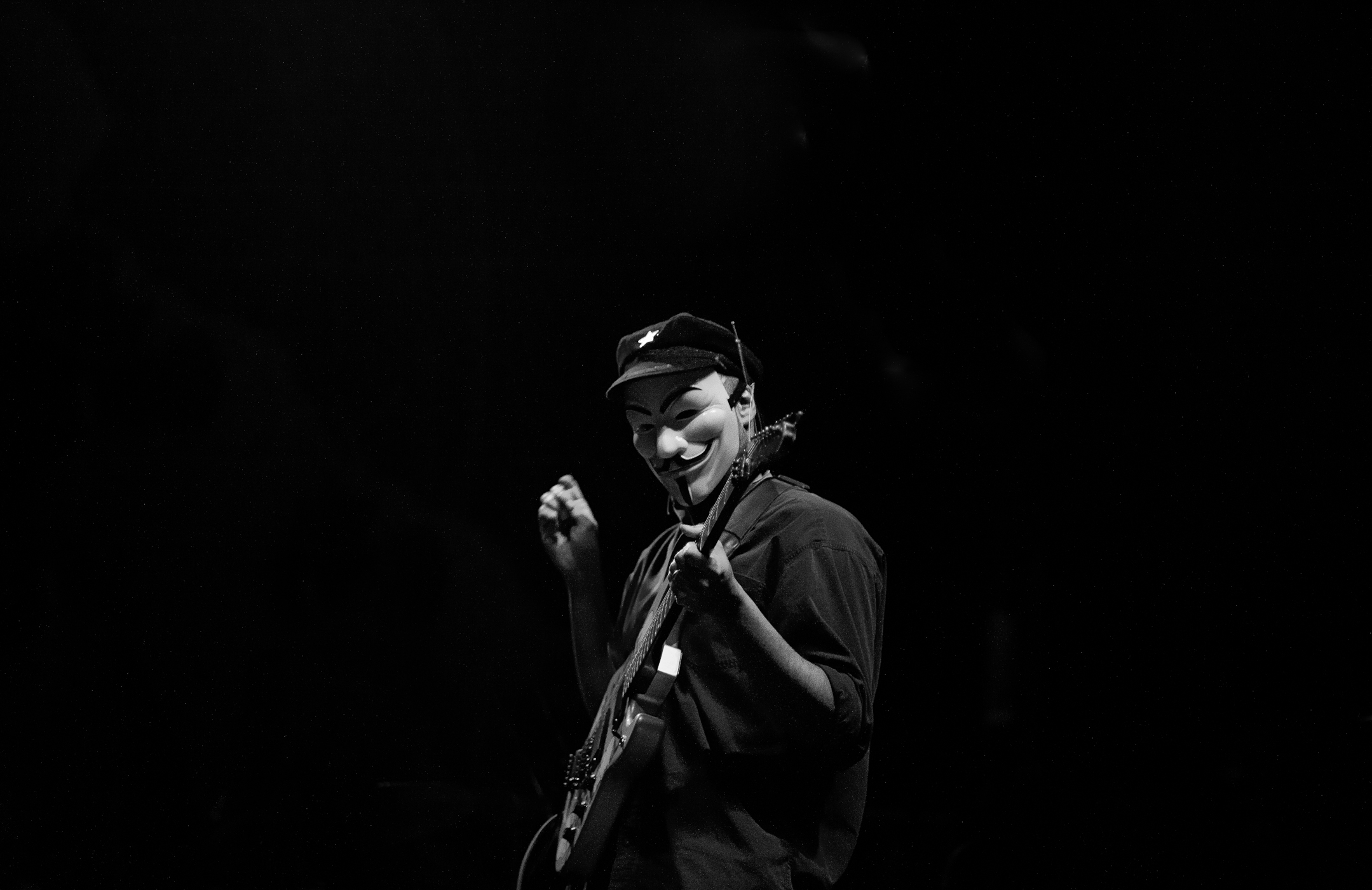

Tom Morello in Brixton recently. Photo courtesy of Tracy Morter

Where do you stand on Anonymous (the so-called hackers) who’ve adopted the V face)? These seem to be fertile times for V-informed protest, it’s very easy to network and meet like-minded people, the state is retreating and V’s very stylish.

DL: Well, I don’t know enough about them, but I guess they’re forming a union and wanting a unifying image, which in one sense is against the true concept of V from the book, where he stands for individualism. But the image in the movie of the mass protest of ‘Vs’ was one of a unified front of resistance against tyranny, so I can understand how that could promote the concept of one group with one collective face. And, of course, the more stylish an image is the more attractive and impressive it is for anyone wanting a brand.

V grew out of the Thatcher regime and was a very British character but he’s translated very well around the globe and through time, did this surprise you?

DL: V used Germany in the 30s as its model, and its spur was the burgeoning power of the National Front at the beginning of the 80s, not the regime of Margaret Thatcher. Though she was not very well liked by Alan and I, and even less liked as the 80s passed, she wasn’t the inspiration for V as some believe, who read that into seeing what Alan wrote in his foreword to the collection. Not surprised about the story’s success around the world because it has universal themes and, sadly, the oppression it addresses is still prevalent in many places around the globe so it always talks about something relevant to its readers. I was surprised at its success in the US market initially because V is a very bizarre and strange-looking character to fit into the superhero dominated landscape of US comic books – and they had no-idea who Guy Fawkes was. But I think a lot of things changed in the US in the 80s, including what we thought was possible in the world of comic books.

The Gunpowder Plot, at Bristol In:Motion 05/11/11 courtesy of Ellen Doherty/Duchess Photography

You were right at the start of your career with V, is it tough to have such a huge success so early?

DL: Oh, it wasn’t such a ‘branding’ success at its beginning as you think. It was published in the US seven years after it was created for British audiences, and only then could you call it a career-changing series for me. It did show what I was capable of, and mark me out, though – but that was the opposite of a bad thing and not tough at all!

Did you know what you were working on would be so influential and so long-lived?

DL: No. But we intentionally created a series that was about something important, from blending two different projects we’d both created separately about characters fighting fascist dictatorships in the UK, so we wanted it to be influential at whatever level we could achieve with it, if only to say something as simple as ‘this will be a bad thing and you shouldn’t let it happen’. I had no idea it would become as long-lived or as valuable to people as it eventually became.

downtown oakland, california on october 26th 2011 by Michael Thorn of Razor Blades And Aspirin

Recently the V sign was painted up by a guy who shot himself in a school shooting, I wouldn’t in any way draw a line between your work and his actions (JD Salinger didn’t shoot John Lennon) but that must upset you?

DL: Well, I hope that the symbol and the mask are never associated with a tragic incident – and thankfully that guy missed, maybe intentionally, all his targets – but there’s no guaranteeing it won’t be. Has the image of Che Guevara ever been used as a protest symbol by anyone carrying out a violent action? Probably. Look at the swastika symbol. That was not designed as a logo for Nazism, but now its only association for most people is with the spilled blood of millions. I hope for better for the symbolic elements of V but hoping’s all I can do.

Occupy The Hague, by Akbar Simonse ©

You’re writing now and illustrating your own work, you must enjoy the freedom this gives you?

DL: Absolutely. There’s nothing like being completely in control of what you’re creating if you have something you want to say. It’s the essence of free artistic expression that it’s unbounded by anything other than your own limits. But collaboration is good if you’re working with someone who’s on your wavelength, which was certainly the case when I was working on V for Vendetta.

What’s your latest project?

DL: I often describe my graphic novel, Kickback, as my latest project, purely because, for no sane reason known to man, it got hardly any promotion on its English-language release, so might as well be my latest project for anyone who likes my work, and is interested in reading about my latest work, and/or seeking it out. It’s a crime story – a psychological police thriller about a corrupt cop in a corrupt police force who decides to change the course of his life. Thematically, it’s similar to V inasmuch as V is about how a society can become corrupt, and how it eventually manages to free itself, whereas Kickback is essentially about one man who does the same thing. Anyway, I’m sure anyone who enjoyed V will enjoy that, too, if they haven’t yet had the pleasure.

Oh, and a continuing project of mine is supporting a great new website that aims to centralise all info on the study of sequential art and cartooning in the UK and Ireland – www.cartoonclassroom.co.uk. It’s meant, too, to promote the use of cartoon art in general education, where it’s proving to be really valuable.

Any royalties on all those masks?

DL: Yes. Though I have no hand in selling them, if anyone suspects I’m promoting their employment as symbols of political protest!

Hartley, aged 2, by his Dad