To receive Vajranala by Senyawa become a Quietus Sound + Vision subscriber

If Senyawa’s last record, 2021’s Alkisah dealt with themes of power, its follow-up Vajranala, released today exclusively for The Quietus’ Sound + Vision subscribers, is an attempt to understand the root of that power. For the Indonesian experimental duo, that root lies in knowledge. When it comes to ‘power’, muses vocalist Rully Shabara, “people will normally think of someone political, but I don’t think that’s the case. The origin of power goes deeper than that.” It’s the shamans, he says, who were the first possessors of power: “If you’re in a village, if you’re considered to have the knowledge to connect people with the realm of the gods, then you will have power before the leader. It’s very fundamental to explore this.”

Senyawa have always held an interest in the connection between humanity and nature. On Vajranala, in particular, they explore how, over centuries, the natural world has shaped our society, the knowledge systems from which power derives, and why that still resonates today. “There isn’t just one way of understanding things,” Shabara explains. “If we get used to receiving or understanding knowledge as we’re being told, that’s dangerous because we think that’s the only truth, but maybe it’s not. Especially if you talk about traditions: everyone has their own tradition which has come from a long history. All of this cannot be dismissed. Times are changing, new norms are coming in. This is the time to revisit ancient knowledge and ask: is it still applicable?”

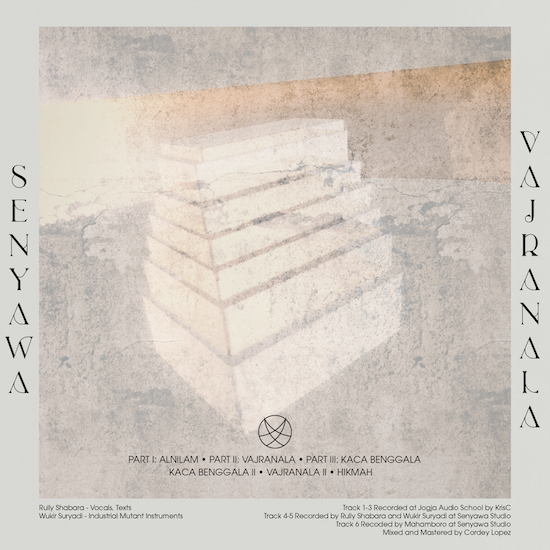

Before recording it the pair embarked on a research trip to the Vajranala from which their new album takes its name, otherwise known as Pawon Temple. It’s the midpoint between Mendut Buddhist Monastery and Borobodur Temple, forming an imaginary straight line. Though Borobodur is a common tourist attraction, Pawon captured their interest more due to its multiple mythologies, including the reason for its location and the Buddhist rituals often performed there. The duo spent three or four days at the temple “downloading”.

“It was a place that was very interesting and ancient,” says Shabara, “so I did a meditation from 2am til 5am by myself. It’s pitch black, dark, scary. But I don’t call it meditating, I call it downloading. Downloading is the process of letting yourself intentionally try to open yourself and receive anything, like inhaling air. When you’re breathing, you’re downloading not just life, but everything that comes with it, because it’s there. This is our process.”

For two weeks afterwards they went their separate ways, each trying to process what they had learned about Pawon. Then, they came together and created Vajranala, on which they explore three different systems of knowledge that might be used to understand the temple. The first half of the album, Shabara explains, should technically be viewed as a single song split into three acts, each representing one of those strands.

The first, for example, refers to Pawon’s connection with the star system. There is a theory that Pawon was constructed to align with Orion’s Belt, or ‘lintang waluku’ in Javanese. This immediately invites parallels with Greek mythology, which in turn makes explicit the fading relationship humans have with astronomy. “When we look at the sky, we don’t think the sky is part of us. But imagine back then. When you saw the stars every night, you would think that the stars are part of you like the trees, because they’re there constantly, and the stars are the same everywhere. We don’t do that anymore so we will become more separated.” The appearance of lintang waluku, Shabara explains, would traditionally signify the beginning of the planting season, which Senyawa references in the third song ‘Kaca Benggala’. To reflect this, multi instrumentalist Wukir Suryadi took a ‘luku’ (traditional Indonesian plough) and transformed it into a giant and careening bowed instrument; for recording, they made a more compact recreation.

“I grew up in the city, where it’s very hard to understand the value of tradition,” says Shabara. “Sometimes, especially for younger people, a lot of traditional values are the opposite of what they believe in, because a lot of traditional values are restrictive, while in modern society freedom is the highest value. Once we respect [traditions], it’s easier for us to understand what their value is, because we’re not judging or separating the value from the tradition. Picking the ones that we like, that’s not respect. That’s also colonialist, only picking what we like. We don’t do that, it’s supposed to be holistic.”

Part of that process means that the release of the album will honour the month of Suro. In Java, Suro is the first month of the calendar year, considered by some to be so holy that one must not marry, fight, or even step outside during this period, lest you face consequences from vengeful spirits akin to those portrayed in 1988 horror film Malam Satu Suro. Suro is not something the pair personally observe, but it extends to their belief of respecting other cultures. “This land is Javanese land,” explains Shabara. “The history that we are exploring is Javanese. So the Javanese believe this is part of their culture. Whether we believe it or not, we have to respect it because we talk about this stuff in the album, this is the way we pay respect: by practising the way they do it.”

Indonesia is made up of a multiplicity of ethnicities, religions, and languages. How does one navigate their own personal context in this environment? “It used to be easier,” Shabara says. But this particular set of circumstances also sets out the stakes for Vajranala’s message of knowledge as power. “More and more people in the villages, they have to adopt modernity. Otherwise, they’re not relevant. The system is put in place for everyone no matter where they are. It’s why it’s important for us to do the album this way. We acknowledge that the sacredness of time for certain cultures is important.”

Another key factor for appreciating the power of knowledge is life and death, a theme which they also touched on in Alkisah. Recording the album, Suryadi says, made him realise that when considering these giant stretches of history, “humans are very small, tiny creatures. The time of the human is nothing.” Asked whether that might simply invite a sense of nihilism, Shabara laughs.

“This is why the album is needed,” he says. “The last song is called ‘Hikmah’,” he points out, a word meaning wisdom, sagacity, philosophy. “You have to have meaning in every human life, no matter how small. Death brings meaning to this. It’s not grim. On Alkisah, the apocalypse is not doom, it’s a reality, and it is for our benefit for it to have meaning. Because life is not sweet. Life is fucking crazy! It’s crazy, it’s dark, full of death, blood, fighting, misery, suffering, oppression. You cannot avoid that. It doesn’t matter how we want to try to fix it, it will always become death and destruction. Without meaning, all of that would be nothing.”

This is why, when Suryadi was offered a piece of land in 2015, despite having no idea what to do with it, he agreed to purchase it. A few years later, they discovered it was actually an ancient site that required proper excavations. Now, Senyawa will erect a physical monument to honour their new release, a fire-spitting temple. They hope to soon establish it permanently through a proper ceremony, in order to preserve the soil and avoid the plague of “toll roads and supermarkets”.

They enlisted a friend to come up with its design using an ancient interlocking method made from red bricks from Bowongan and andesite sourced from Merapi. He carved these stones based on the Vajranala texts. But the temple also has another unique feature: “it can spit fire”, Shabara grins. Fire, he says, is part of the Buddhist cleansing rituals; it also makes up the second half of Vajranala’s etymology (‘vajra’ meaning ‘thunderbolt’ and ‘anala’ meaning ‘flame’). How fitting that its temporary erection at Borobodur came the day before the death of Queen Elizabeth.

For those unexposed to the world of Senyawa, Shabara hopes that it will lead them back to the band, and in turn Vajranala. “Our hope is that they will find out, because why the fuck would Senyawa build a temple? They’ll automatically ask that question. That’s why we built it, so when they ask that question, they’ll try to figure it out. So that’s why a monument is needed, not just an album.”

To receive Vajranala by Senyawa, as well as a host of other benefits including exclusive essays, podcasts and playlists, and loads more specially-commissioned music, become a Quietus Sound + Vision subscriber. You can do so here