To receive Futhorc: New Sonic Rites For The Old English Rune Poem by Rúnesine, become a Quietus Sound And Vision subscriber

We first performed Futhorc: New Sonic Rites For The Old English Rune Poem as Rúnesine to open the Acid Horse festival in August 2023. For this recorded version, Robert intoned the Rune Poem at the formerly Anglo-Saxon church in Alton Priors, Wiltshire, while Mark recorded electronics, and mixed the piece with Robert on percussion / frame drum and rattle, at his Black Lodge studio nearby.

*

Rune: Robert Wallis

Some years ago, while sat at a prehistoric chambered tomb in Brittany, the megaliths quartz-rich, dazzling in the sun, and sky-seeking silver saplings growing amongst the scrub, I shook my set of runes, made a cast and received the response, beorc (birch):

Beorc byþ bleda leas, bereþ efne swa ðeah, tanas butan tudder, biþ on telgum wlitig, heah on

helme hrysted fægere, geloden leafum, lyfte getenge.

Birch has no fruit, bears shoots with no seed, a leaf laden crown amongst high shining

branches, delightful garland aloft in the sky.*

I began to recite the Old English text, but reading from paper felt formulaic, lifeless, interrupting the magic of the ritual moment. Over time I committed the rune poem to memory and learned to intone it from the heart, as a galdr, a spell.

The inflection, timbre and rhythm of the language, hoof-beating drum and clanging bell-rattle, conjure a charm of making, for magic, healing and inspiration.

*

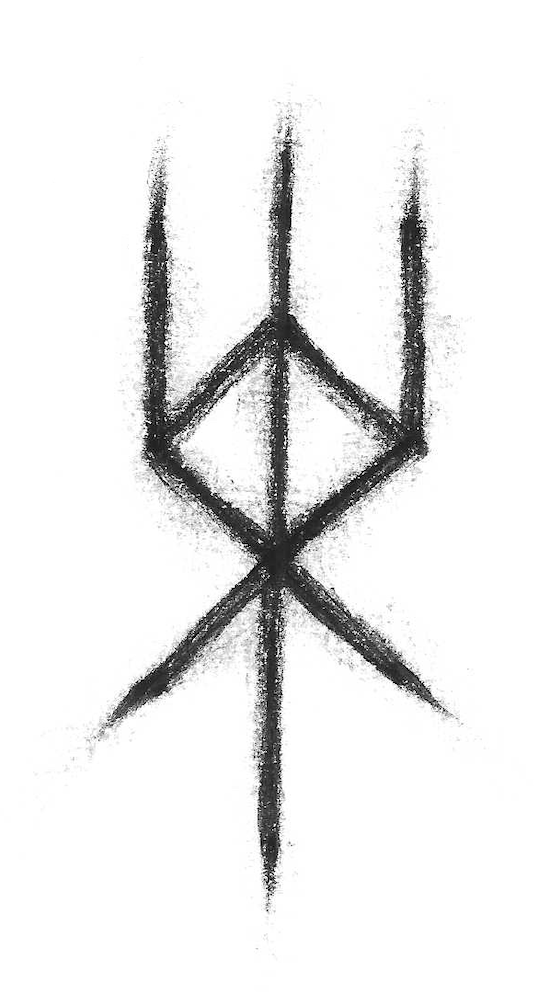

The Old English rune poem, known as the Futhorc after the first six runes – ᚠᚢᚦᚩᚱᚳ fuþorc – was written down by an anonymous author in the 10th century. The poem has pagan themes which reflect an earlier oral tradition perhaps stretching to before the conversion to Christianity. Each stanza of the poem is a riddle, the answer to which is a specific rune (Old English rún, mystery, secret, whisper) representing in glyphic form an element of the lived early medieval world. So, ‘the whitest corn’ that ‘swirls aloft, tumbles in gusty winds, then turns into water’ is hægl (hail), its rune, ᚻ.

Carved into slivers of wood or stone, cast with intent, the runes offer an effective oracle for Heathens today, and the Old English rune poem a context for interpreting its meaning. Approached as a galdr (spell) the Old English text of the poem is a magical formula for invoking the runes, their powers, their mysteries. The scop (poet), læce (healer) and drȳmann (magician) committed their word-hoard, their spellcraft, to memory.

*

For an archaeologist and animist Heathen, the ancient English landscape holds a wealth of living lore. Making pilgrimages across Wessex, I am a way-farer, from Danebury to Wayland’s Smithy, from Avebury to the grey wethers of Giants’ Valley. At Wōdnesbeorg, I am a mound-sitter, a seiðrmann. Nearby All Saints is a nyd-clea, a need-nail or node that brings prehistory, the medieval and the present into magical dialogue. And the hollow yew tree, ᛇ, heard hrusan fæst, hyrde fyres, wyrtrumun underwreþyd, wyn on eþle (hard, fast in the ground, a keeper of fires, roots writhing beneath) is Yggdrasil, made from Ymir’s flesh. Hung there, Wōden seized the runes, shrieking the galdr, ‘runes of wisdom, runes of woe, runes of healing, evil to slow’, the god-given gift of the Futhorc.

*All translations and original poetry from Nathan J. Johnson and Robert J. Wallis, Galdrbok: Practical Heathen Runecraft, Shamanism and Magic (London: Wykeham Press, 2022).

Sine: Mark Pilkington

It’s the kind of thing you find in folklore or the tales of Arthur Machen: a tiny, empty and very ancient church, standing in an open field between two picturesque hamlets of thatched roofs and muddy lanes. A church with a secret.

My friends Neil (a longtime musical collaborator) and Hillary Mortimer first showed me All Saints Alton Priors over two decades ago, back when Neil was editing the much-missed folklore and archaeology ‘zine Third Stone. I now live just a short drive away and visit regularly. We recorded Robert’s Rune Poem recital here late last year, while Michael York and I also recorded bells and pipes in the space for our Teleplasmiste album To Kiss Earth Goodbye in 2018.

Neat and well-preserved, like the villages that border it, All Saints is nestled in a wide, flat valley between the voluptuous, undulating hills – known to some locals as “the sleeping goddess” – of the North Wessex Downs, and the more austere, militarised plateau of Salisbury Plain to the south. Parts of the church date to the 12th century, and it stands on the edge of what was once an Anglo-Saxon village, comprising a relatively-large 50 households by the time of the Domesday Book.

Its neighbouring church, St Mary’s – only 200 metres, and two streams, away in Alton Barnes – is even older, and remains in use. Large yews, at least 1500 years old, grow in both churchyards, the one at All Saints with a split wide enough to accommodate a couple of witches or pagans.

On first entering All Saints, you might not notice anything unusual, but keen eyes will spot two brass eyelets on the floor, one in the northeast corner of the church, the other in the northwest. These are attached to trap doors built into the floorboard, beneath which, unknown, or at least forgotten, until the church was renovated in the late 1970s, are two flat sarsen stones. The one nearest the entrance is broken and has a narrow hole passing through it, making it look like a curled, sleeping animal; the other is considerably larger and less distinctive, though there’s a shallow bowl worn into one end.

Sarsen stones – the name denoting their ‘Saracen’, or un-Christian nature, to 18th century countryfolk – are no strangers to the area; this hard sandstone sits upon the chalky soil beneath, remnants of islands in Pangaea’s Cretaceous seas. The surrounding downs and valleys were once littered with an abundance of these stones, also known as ‘grey wethers’ for their likeness to sheep, and Lockeridge Dene, four miles to the northeast, still is. Sarsens were used to construct the vast triple circles at Avebury, about five miles to the north, parts of Stonehenge, about 15 miles south, and the many neolithic tombs in the area, as well as a great many more walls and houses in the past couple of hundred years. Significant parts of Avebury, and other stone circles, some now lost, also became walls and houses, but that’s another story.

A few details point to the All Saints sarsens’ significance, beyond the fact that a church was built over them, playing into the romantic notion that Christians sought to dominate and erase the sites of their pagan predecessors. The stone nearest the church entrance is both neatly broken, and has a hole through it. Sarsens often carry holes where Jurassic palm trees were rooted when they were sand, but holed stones seem to have carried particular significance, as portable hagstones still do for some of us. The clean break across the stone is suggestive of a deliberate act, perhaps territorial, or spiritual, defilement of a once important structure.

While we don’t know whether these stones were once part of a larger structure – a circle or burial chamber for instance – there are reasons to believe so. Their location was undoubtedly significant: lying directly between a large spring and the ancient Ridgeway, a 5000-year-old network of paths that ran from Lyme Regis on the south coast, to Hunstanton in Norfolk. Although the visible route peters out just south of Alton Priors, you can follow it north up Walker’s Hill, and all the way to Avebury, from where it continues to the Chilterns, via Iron Age hill forts and the spectacular 3000-year-old white horse at Uffington.

Just to the northwest of the church a series of springs bubble through chalky silt, a source of drinking and bathing water for millennia and the origin for the river Avon, which flows via Durrington Walls – a major neolithic settlement – and Salisbury to Hengistbury Head on the south coast. Beyond their obvious practical resource, springs have always had immense significance as sources of life and death, worship and sacrifice. The spring here is cut into two pools, perhaps reflecting the ancient practice of creating separate bathing sites for humans and animals.

Looking directly out over Alton Priors from Walker’s Hill is the huge neolithic long barrow known to us as Adam’s Grave, and to the Anglo Saxons as Wōdnesbeorg. This group burial chamber would once have been visible for miles around, a chalky white beacon, or sentinel, reflecting sun and moon light across the valley. I like to imagine that the barrow was a response to the natural near-pyramid of neighbouring Picked Hill, which may have seemed to be the work of an older people, perhaps giants, perhaps gods, impossibly ancient even to the area’s neolithic inhabitants.

Piecing these elements together – an ancient ‘A’ road leading, via a prominent long barrow, to the largest stone circle in Europe; a large spring; sarsen stones, an Anglo-Saxon village and church – and you have what would appear to be a site of great importance. A place to rest, drink, eat, wash, and worship; akin perhaps to a church along a pilgrims’ way, but one that existed for millennia before Christians came.

Without archaeological work, we can’t know whether the stones beneath the church were part of a larger neolithic site or structure; perhaps they were left there while being transported from one location to another. Either way, we can safely assume that they, and any other stones that existed here, would have been important to the valley’s first pilgrims and settlers – we can only imagine how.

It’s hard not to conclude that there was a site of significance here in Neolithic times, and that Anglo Saxon settlers – who also raised their own standing stones – developed it with construction of their own, which eventually became the church we see today. Local historian David Carson told me that the first church would have sat upon a raised mound in marshes on the edge of the settlement, reflecting the mystery and power that water held for our ancestors.

All Saints has become an important part of my family’s home landscape. We enjoy it, use it and engage with it, practically, aesthetically and ritually, like many who were here before us, and many who will come after. Recording there for Runesine and Teleplasmiste, writing this text and sharing it with you, have all become parts of that process: a further enfolding with, and connecting to, this very special site.

"Might Anglo Saxon villagers have heard the Rune Poem here 1500 years ago?” I asked Robert during our recording. His inner historian over-rode his inner mystic: “Probably not”, he chuckled. My own inner romantic prefers to believe otherwise.

Wæas thu hæl!

Runesine:

Robert J Wallis – voice, drum, rattle – is an academic, author and Heathen.

Mark O Pilkington – electronics and production– is an author, publisher and electronic musician.

To receive Futhorc: New Sonic Rites For The Old English Rune Poem by Rúnesine, as well as a host of other benefits including exclusive essays, podcasts and playlists, and loads more specially-commissioned music, become a Quietus Sound And Vision subscriber. You can do so here