The internet, in the infant years of the 21st century, was a maximalist experience. It was defined by cacophony – a frenzy of pop-ups, gaudy webpages, brightly coloured windows, all competing for space and prone to sudden freezes and deathly jams. The internet had not yet adopted the visual language of sleek millennial minimalism. Not minimalism for its aesthetic worth, but as shrinking apology for what the experience might be doing to our lives.

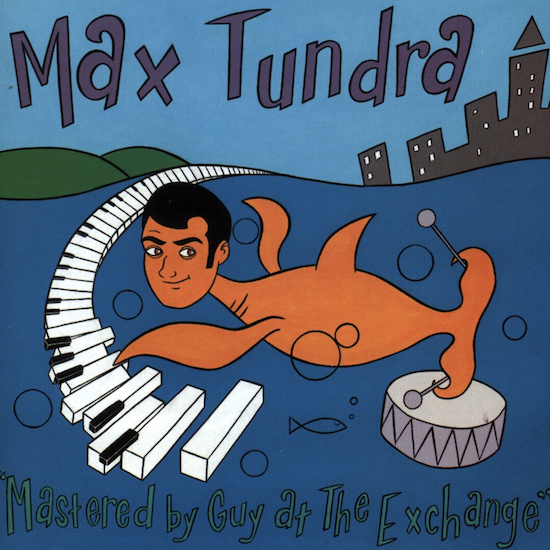

This sensation is closely evoked by three records released during those years by Max Tundra, the alias of the South London electronic producer Ben Jacobs. In electronic music, Jacobs was an outlier, but across Some Best Friend You Turned Out To Be, Mastered By Guy At The Exchange and Parallax Error Beheads You, Jacobs made music unmatched in early 21st century Britain for the richness of its ideas and the exhilarating potentials it unlocked. This music would help lay the foundations for significant trends that would come to pass.

As soon as Jacobs was aware of music, he was finding ways of bending it to his will using technology. Born in Camberwell in 1974, the infant Jacobs loved singing or taping bits of melody – usually the Joni Mitchell or Steely Dan in his parents’ record collection – and speeding them up on primitive home cassette technology. Using little more than home taping, he would craft audacious mixes that built and dissipated tension recklessly, the child quite unaware that this might be something called DJing. Songs from adverts, incidental music from video games, all the detritus of modern life. The first album that he bought with his own money, 1984’s (Who’s Afraid Of) The Art Of Noise? by The Art Of Noise, would have similar collisionary instincts.

Jacobs’ childhood was a tale of two computers. First, the BBC Micro, an educational computer rolled out in British schools during the early 1980s. Sticking the microphone of a tape recorder against the computer’s fun-size speakers, Jacobs would produce his first demos. The Amiga 500, however, would legitimately change his life. Launching in 1987, the Amiga 500 would be particularly beloved of hardcore and junglist producers for its transformational four channel stereo sound and its gluttonous bottom-end sub bass. Thirteen-year-old Jacobs blew his Bar Mitzvah money on the device.

No sounds emerged from the Amiga itself, but instead the computer controlled various samplers, car boot sale synths and analogue sounds in Jacobs’ home studio. “I look at columns of numbers all day on the screen of a black and white television” Jacobs explained in a 2008 press release. For an electronic producer, he sure as hell tried to avoid electronics where possible. If a sound could be made organically, then he would do it. If he wanted trumpet on the record? Jacobs learnt trumpet. These analogue sounds would form the raw material with which Jacobs would then rearrange to the point of sonic delirium.

In the 1990s, there was no shortage of bedroom Amiga entrepreneurs, but what separated Jacobs was his tastes. To be sure, he was interested in – and influenced by – the electronic pyrotechnics of Aphex Twin and Autechre, but what really got him out of bed in the morning was a love of artists like Yes, 10CC, XTC, even Nik Kershaw and weird McCartney. Disparate artists united by a specifically English prog maximalism with a focus on studio invention and an unfashionable defence of full fat melody. He wondered what would happen if he could apply these lessons to electronic music? In a 2008 interview with Resident Advisor, Jacobs pointed to a moment on XTC’s 1986 album Skylarking. “At the start of ‘1000 Umbrellas’, where it (leads) in from the song before, and it suddenly changes the time signature, and just the way it does that is absolutely phenomenal and breathtaking. And to me that’s one of the sexiest moments in music.” Jacobs was onto something and he knew it.

In 1997, he sent a demo to Warp. This was not the 1997 of Urban Hymns and Be Here Now, but a better 1997 of Dots And Loops and Moon Safari. The Sheffield label wanted to release the track immediately. That release, ‘Children At Play’, was a thirteen minute odyssey of prog electronica, ascending from a kind of 8-bit bhangra to pulverising jungle, up again through hard funk before settling on a thrilling choral sample from a forgotten 1980s modern classical record. Warp wanted to know what this project was called. Jacobs toyed with names like Natalie, Bod, MTC, Optimus Prime before finally settling on Max Tundra. The first word is important here. This is maximalism. Jacobs was an ideological defender of the idea, underlined in interviews by cheekily declaring himself “bored of Canada.”

It’s unclear why Jacobs didn’t stay with Warp, instead signing with Domino for what would become 2000’s Some Best Friend You Turned Out To Be. The only instrumental Max Tundra album, this is 45 minutes where idea piles upon idea, an attention deficit obsession with multiplying sonic spectacle. Whenever the album feels solid, you’re stood on a trapdoor. It dispenses great ideas like confetti – take ‘Lausanne’s thrilling games with audio static (a few years before Ghost Box hauntologists were patting themselves on the back for much the same) or the terrific jammed CD-J sound on ‘Cakes’. Pitchfork – perhaps Tundra’s sole reliable champion – correctly observed that the record was “undeniable proof that a record can be chaotic without succumbing to dissonance”, terming it “the kind of dynamic, creative record that should be heard by as many people as possible.”

It would be Jacobs’ next move, however, that would produce his finest album with the longest tail. Had you purchased Some Best Friend You Turned Out To Be at the time, you likely had a set of assumptions about its creator based on the limited information available – the aesthetics of electronic music at the time, the sounds on the record and the moody, abstract artwork it was contained in. What listeners to Mastered By Guy At The Exchange in 2002 did not expect, what perhaps took them by surprise, was the geeky, white-boy vocal that opened the album. Punters were expecting Squarepusher, and were greeted with a sweet, clarion vocal and nursery rhyme melody that sounded, well, like something off a Belle And Sebastian record. Jacobs had outed himself for what he was – a friendly, T-shirt wearing geek with a penchant for ending DJ sets with an eight minute version of ‘Goodbye, Farewell’ from The Sound Of Music – and this would cast him in a genre of one. Electronic audiences could not fully embrace him, whilst an indie landscape at its most conservative – giddy over New York garage rock revivalists – simply ignored him. Entry into the actually existing pop world was a non-starter.

“The first time round I wanted to invent eleven new types of music," outlined Jacobs at the time, “this time round I decided to alter twelve existing types of music." What this achieves is an album where Jacobs applies his maximalist Amiga methodology to pop, R&B, soul, power pop and prog, creating an entirely singular record in the process.

The next few years will likely see plenty of media stakeholders insistent on explaining that the British guitar music of their youth – the New Rock Revolution invented by NME editor Conor McNicholas as an initially successful but ultimately self-defeating ploy to reverse declining magazine sales – was more interesting and valuable than might be apparent. The #IndieSleaze moment is already a vanguard action of this. Stick a pin in any minute of Mastered By Guy At The Exchange and you will find more sonic ideas than the entire 8CD deluxe box set of that entire era. That is not, however, to say that Jacobs’ work was not entirely without friends in that unlovely decade. In its primary colour optimism, it’s matched by the early sampledelica of The Go! Team, and shares a fast and loose approach to genre with the wilder corners of Xenomania’s catalogue. It made sense when Jacobs began remixing acts like Hot Chip or Franz Ferdinand, but with distance his work outlaps their 4/4 indie disco fidelity. Take a track like ‘Halting’. With its gorgeous romanticism and clipped power chords, it shares plenty of DNA with a straightforward indie track, but instead Jacobs stuffs new sonic ideas into every conceivable gap (and even a couple of inconceivable ones).

It’s ‘Lights’, though, that is the sound of a pop yet to come. The culmination of Jacobs’ lifelong interest in varispeed vocals, the wildly ambitious vocal track becomes a riot of cut-up, restitched and repitched phrases. In total, the track exaggerates pop tropes to the point of cleansing itself of pop tropes. See also the sugar sweet ‘Lysene’ – sung by Jacobs’ sister Becky, of folktronica outfit Tunng, – or the Super Mario at the rave of closing track ‘Labial’. On first contact, it all feels too fussy, too colourful, too much. It’s akin to being force-fed Tangfastics. By your third or fourth listen, there’s a dopamine rush in your brain decoding it into perfect pop (even if it is perfect pop with a middle-class English accent and name-checking David Toop, Michel Gondry and the second studio album by Yes.) Jacobs’ masterpiece, this is an album containing an embarrassment of possibilities.

Did anybody care? Not really. A buzzy reputation on music forums gave the record some velocity in its ongoing slow-motion snowball towards minor cult status. Jacobs kept busy, spending Friday nights down his local boozer’s karaoke night firming up the top end of his vocal range on Destiny’s Child hits. This regimen would prepare him for the recording of Parallax Error Beheads You. Released in 2008, it may be lighter on innovations than his first two records, but instead sees Jacobs consolidating his ideas into a properly pop formula.

In interviews at the time, Jacobs would talk about the potential crossover sounds of Scritti Politti or Stereolab. The effect, though, was best surmised by Jude Rogers, writing in the Guardian that the record sounds an awful lot like “Prince replacing his Viagra with Ritalin”. It’s a more lovelorn record too – Jacobs outs himself as a wife guy who quests for love on MySpace, Friendster, eBay and Google Image Search. These dated references are to be enjoyed; the record collector rock ambition of timelessness always creates art that pulls its punches. The album’s centrepiece was eleven minute closing track ‘Until We Die’. Inspired by the Trevor Horn produced late era Yes single ‘Our Song’, it took a full nine months to record, its extensive production threatening to overwhelm the memory of the Amiga.

Within a year of that album’s release, Jacobs declared that the final part of the trilogy was in fact the very last Max Tundra album. The three albums would be entombed one side of the global financial crisis – Parallax Error Beheads You would come out during the nightmare weeks of the Lehman Brothers crash – and Jacobs instead would commit to very different work on very different computers, working an office job. Max Tundra may have laid dormant, but his influence would begin to take shape.

When Charli XCX slid into the DMs of producer and PC Music founder A.G. Cook in 2015, it would be the starting gun on the mainstreaming of Hyperpop, something which had begun as a minor rupture within British electronic music. At time of writing, the genre has become a global business with all the porous definitions that such success entails – it’s a highly popular Spotify playlist, and subject to New York Times podcast discussions. A.G. Cook had been a teenage Max Tundra fan. “I never fully stopped listening to it” explained Cook to Loud & Quiet in 2020, “he’s retroactively become part of the PC-affiliated world, especially as it’s getting other terms like Hyperpop. I find it satisfying to work with people who’ve made music after PC music. It’s nice knowing you’re part of this timeline. Hopefully he feels the same.” The best working definition of Cook and PC Music’s framework came from musicologist Adam Harper in 2014, writing in Electronic Beats.

“A network of younger producers and DJs are not particularly inclined towards the more po-faced and straight-laced tastes and traditions, be they the screwface macho mainline of the old UK hardcore continuum or the leagues of frowning analogue avants or the Right and Proper Preservation of House. They’d rather have the even more euphoric, poppy, often faster-paced melodic hardcore with pitched-up vocals—the whole thing pitched up really, often so’s there’s no real bass to speak of—and a pinch of weirdness thrown in.”

This is a description of a music thats only real antecedent is Jacobs. Think about what separates Some Best Friend You Turned Out To Be and Mastered By Guy At The Exchange – PC Music would revel in that rejection of electronic music’s cult of anonymity and minimal moodiness. There is no better word for the varispeed games of a track like Lights than Hyperpop.

As PC Music flourished, Jacobs suddenly re-emerged with an audacious roll of the dice. He had coaxed US duo Daphne & Celeste – of bratty Y2K cheerleader chant ‘U.G.L.Y.’ fame – out of retirement, a pop flex comparable to Pet Shop Boys using Dusty Springfield or the KLF’s teaming up with Tammy Wynette. Daphne And Celeste Save The World was released in 2018, and by barely moving an inch from his early 2000s work, Tundra was suddenly making music that fitted exactly with the scene around him.

Promoting these very reissues, Cook went further in articulating his credit to Max Tundra. “Mastered By Guy At The Exchange is a true cult album, a playful monolith that sounds both nothing and everything like the 2000s. Stumbling across it as a teenager, it reinforced a hunch I had: that music is a place where anything could happen, and total chaos could be held together by the lightest of pop hooks.” By digging into an ignored English maximalist prog tradition, Ben Jacobs changed music and laid down the fundamentals of some of the most important pop shifts of the last decade. Some prophet he turned out to be.