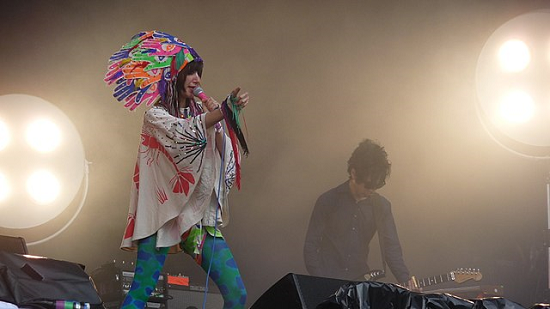

Klaxons. Photo from WikiMedia Commons

Every generation has a pivotal moment they remember more fondly than how it actually occurred in order to enhance it. Spike Island being an era-defining gig, despite the fact that you couldn’t really hear all that much and the acid you took left you a bit wonky; maybe it was Radiohead’s Glastonbury 1997 appearance that you proudly recall even though you couldn’t see a thing because someone had a ten foot flag in front of you; or maybe the halcyon days of acid house on the Hacienda dance floor but in reality you didn’t swing by until 1994 and it was more comedown than party.

Well, millennials now seem to have one of these misty-eyed moments to bask in with all the recent talk of indie sleaze. Except rather than embellishing something to heighten a memory, it’s making up an entire new framework to fit them into.

A quick bit of background: Indie Sleaze is an Instagram account posting pictures from the mid-to-late 00s indie/ electro/ party scene that has now been contrived into existence as a genre/ label and is apparently making a comeback. There have been articles written about it in NME, Dazed, VICE, the Guardian, The Cut, Harpers Bizarre, Vogue, Esquire, Stylist, GQ, Refinery29, and even that bastion of burgeoning youth culture content, The Daily Mail. Indie sleaze is “back back back” according to NME. Except it’s not. Because it never existed to begin with.

Indie sleaze makes perfect sense as an archive-based Insta page. It documents an era that took place long enough ago that it holds curiosity for those who weren’t old enough or plenty of nostalgia for those who were. It’s a snapshot of the final generation of young people who existed before the full switch to online life, social media and constant documentation. There’s an understandable attraction, romance even, to that and it’s easy to tap into the purity and wild-eyed hedonism of it all – the last time people could party like nobody was watching. It is perfect Instagram material and is a fun place to lose yourself in for a bit while cringing at the memory of the time you spray-painted a pair of winklepickers gold.

The whole thing gained more traction when trend analyst Mandy Lee uploaded a video to TikTok citing an “obscene amount of evidence” that indie sleaze is coming back. She opted out of including any of the evidence but even if this does turn out to be the case, then fine, I’m not contesting fashion predictions here. Fashion mirroring what kids were wearing 20 years ago is not necessarily reflected in the music being made or what’s currently in their headphones (which will apparently now be wired as opposed to wireless in tribute to indie sleaze’s supposed love of antiquated technology like polaroid cameras).

Nostalgia and the 20-year cycle are common in music. It’s no big surprise that a bunch of people pushing 40 start getting a bit warm and mushy remembering when they were 23 and full of pills and Red Stripe while listening to Soulwax. It’s human nature. It’s nice to remember good times with old friends.

The Strokes. Photo by Roger Woolman / WikiMedia Commons

It can even be a positive thing, says Dr. Clay Routledge, who is a psychological scientist at North Dakota State University and the author of Nostalgia: A Psychological Resource. “A lot of people have this view that nostalgia is just people stuck in the past,” he says. “There certainly are people like that but for the most part, from the research we’ve done, it seems to be more the case that the past is more a source of inspiration. It can increase creativity, as well as having an imaginative fantasy component to it as well.”

But why is it so common around this 20-year cycle? Or with people who are on the cusp of middle age? “Our research shows that when people are feeling uncertain or anxious or they don’t know what’s going on, they often become nostalgic,” Routledge says. “People tend to become more nostalgic when there’s a lot of changes going on in their lives or in society.”

Which of course can, understandably, mean a feeling of instability because the world is a giant screeching ball of chaos at the moment, but are some people beginning to feel irrelevant or out of step with youth culture as the big milestones of their lives – children, jobs and houses – take over? Are they clinging onto something that makes them feel part of something again? “People want to have cultural significance,” Routledge says. “We’re a very youth driven culture but also part of the way cultural transmission works from generation to generation is looking for connecting points. Like the newer Star Wars movies for example. We need these intergenerational connection points.”

However, the 20-year cycle, or the buzz around a genre comeback, is at least usually linked to something tangibly evident in what’s being produced now – you usually work back to trace the roots of something new exploding. There’s been piece after piece written about indie sleaze with very little reference to anything being made beyond the insta account, the odd fashion reference, or musically, at best, references to modern bands like Wet Leg crowbarred into the narrative with such force that it could bend metal.

Where is the current crop of bands going to bat for all these supposed in vogue indie sleaze bands? Who even sounds like any of them? Jockstrap are given as an example in the NME article that supposedly embodies this indie sleaze essence. Although they appear more to be a band that perfectly encapsulates the now, propelled by a post-genre attitude, utter disregard for conventional structure, and a fierce experimental approach that lacks the obvious hooks that defined so much indie/electro stuff. Also not sure I heard a huge amount of violin doing the rounds back in those days?

100 Gecs apparently sounding a bit like Uffie is also evidence of something afoot, as is Beabadoobee saying her new record would sound “very 2006”. Which upon further investigation means it’s inspired by the Canadian indie pop band Stars, as well as Stereolab – hardly two peak contenders for the darlings of indie sleaze.

What’s become increasingly bizarre about the notion of indie sleaze is this retrofitting of a term that was born in 2021 to create an imaginary genre from the 2000s. In VICE, Marcus Harris of indie club night White Heat, describes indie sleaze as “the point where electronic music intersects and becomes electro-rock, or electroclash with more of an indie leaning” before throwing bands like Yard Act into the mix as contenders to spearhead the revival, which only further muddies the already deeply muddy waters. People are tripping over themselves in an attempt to define and categorise something that does not exist.

Late Of The Pier. Photo from WikiMedia Commons

If we use mid-noughties indie as the most obvious comparative example, then it was at least very clear what was being referenced there: Franz Ferdinand proudly paid homage to Josef K and Orange Juice, the jagged guitars of Gang of Four could be heard buzzing through Bloc Party etc. Those who heavily referenced older bands and ended up being dubbed a scene or movement were at least, by nature of doing that with young fresh eyes, attempting to move things forward and do something new. There was an element of progress and development.

With indie sleaze, there appears to be little else going on other than some people wallowing in the past while trying to convince themselves that it, or maybe even them, possesses some sort of contemporary relevance. As though if one keeps saying that something is happening enough times then it will eventually become true. It feels like the signs of a creeping millennial midlife crisis. Some of the stuff being posted under the indie sleaze hashtag already indicates a seemingly inevitable generational shift into ‘it was better back in my day’ territory. The next generation of Weller haircut mods or acid house dads are now seemingly upon us.

I should probably add at this stage, I’m not some sour faced grump who hates the whole scene and music. In the words of James Murphy: “I was there.” (In fact by indie sleaze logic, that song could probably do with a lyrical refresh to include indie sleaze couldn’t it.) The gold winklepickers I mentioned earlier? They were not hypothetical. I literally spray painted a pair of shitty Burton winklepickers gold to go to Dot-to-Dot festival in Nottingham. I had dyed black hair, wore eyeliner, braces, ties, neckerchiefs, polka dot shirts, and blood-draining tight jeans.

I even wore blank-framed glasses with no lenses for a bit.

The first night my partner and I met all those years ago was in a grotty Sheffield house (mine), drinking shoplifted white wine, snorting crushed up pills and listening to Patrick Wolf. I was a living, breathing, insufferable, definition of what would constitute indie sleaze.

But despite a fondness for organ-destroying substances, I have managed to retain a semi-functioning memory and so while part of me thinks: so what, stop being so po-faced, let people have a bit of fun, another part of me can’t help but think: hang on. When you’re watching people in their 40s debate online about the definition of a musical genre that literally never existed, it’s difficult not to wonder if a new cultural phenomena is taking shape here? A sort of next level nostalgia that wilfully overlooks reality in favour of enhancing one’s youth.

There’s no disrespect meant whatsoever to the creator of indie sleaze. She created something fun and I’m sure when she started putting together sweaty pics of Karen O lookalikes in clubs, she didn’t envision being asked to define it as a musical genre to NME a year later. Similarly, if young people decide to call the whole thing indie sleaze and get stuck in then fine, great, have loads of fun with it. It’s an easy term to reference something you discovered that existed before you. But while it may be a harmless catch-all term some young people are retroactively fitting, does it say something more substantial about ageing millennials trying to place themselves as part of a modern trend that they can link to their own youth? It’s one thing to align yourself with a 2021 fashion term you feel actively defines your own youth, it’s quite another to talk about it as though it was definitely categorically a thing that you participated in.

“There’s two ways of looking at it,” Routledge tells me. “The cynical way is that these are totally distorted memories. The more positive side is that as humans it’s really important to have a story arc, a narrative. It is kind of like filmmaking and the reality of the past is like the raw footage. Well, that doesn’t make for a good movie. What makes a good movie is when you go in there and you find the pieces that you think tell the story you want to tell. So I don’t think it’s total fiction, that footage is there right? But where it becomes more creative, and more imaginative, is how we make editing decisions.”

There’s also a strange, and slightly worrying, exceptionalism that is accompanying a lot of these articles about the scene. There’s often a keen, yet vague, emphasis on how it was such a strong and wonderful time for DIY community spirit in music and how we’re looking at a return to times like those. But that never went anywhere for a second. That is absolutely not something that should be in any way deemed unique about mid-noughties indie/ electro (a hefty chunk of which was major label fodder anyway – not to mention the vast wealth floating around some of the NYC scene).

If anything, the DIY community across all genres, from underground electronic to avant-garde to punk, is stronger than it has ever been (certainly in the UK). Communities and co-ops are running brilliant and inclusive spaces under incredibly hard circumstances after a decade-plus of austerity and with much higher rents. In doing so they create a sprawling underground network that is a vital part of music’s cultural ecosystem.

“I feel like with the indie sleaze subculture, 15 years ago, community, art, and music were so powerful,” Mandy Lee told Vogue recently. "That’s what brought people together.” Olivia, the creator of indie sleaze, also told NME: “I feel like indie sleaze was a lot more community-driven than everything that happened on the internet afterwards.” Even though she’s from Toronto, and maybe things are wildly different there, it’s kind of insulting to suggest that this has been absent in music communities and scenes over the last 15 years and that a fashion-based trend is somehow going to save the day and bring back to life the dead spirit of community cohesion through artistic expression.

Yeah Yeah Yeahs. Photo by Jim Baldwin / WikiMedia Commons

Also, it completely feeds into this bogus notion that gen z are just a bunch of teetotal bedroom-dwelling computer geeks who don’t get out into the real world. Everything from nu-jazz to drill to the goings on in places like the Windmill in Brixton or the White Hotel in Salford, were built on the foundations of community and collaboration. In countless European countries, and even in the cripplingly expensive New York, a strong community of DIY venues and scenes continues to thrive.

Similarly, this line that a post-lockdown appetite for hedonism is somehow linked to indie sleaze is utterly bizarre. It’s a suggestion that keeps being repeated but with nothing to back it up. Surely any post-lockdown search for mind-altering escape in young people is rooted in having been, you know, locked inside for two years? And could equally be applied to anything from techno to UKG? Not because of the rise in “amateur-style, in-the-moment photography, TikTok music mash-ups, and now-vintage technology”?

The indie years were unquestionably a party heavy scene but I’m not sure it was any more hedonistic than any other era or scene that went before or came after it. This suggestion is just another tweak on the same tired cliché that’s been circulating the last two years about how we’ll get another roaring 1920s post-pandemic. True, pure, hedonism does not come from prescribed trend forecasts; it exists naturally and in the moment, and it has been doing just fine all by itself.

The whole thing just feels like such a weird, tenuous, desperate grasp for something that isn’t there. A bit of a front. One that people are using to mask the reality that the music they like, or make, has been deeply out of fashion for some time and are jumping on an opportunity to convince themselves its back.

What’s really odd about it is just how immediately people have swallowed it up and digested it without question. “It’s fascinating,” says Routledge of it all. “I wonder if it becomes like a self fulfilling prophecy? Like the buzz just makes it come back? Like a viral marketing campaign.”

Indie sleaze is hardly a grave rewriting of history with profound consequences, but it’s Tipp-Exing over (little 00s reference for you there) a small part of music history to better fit around a zeitgeist narrative. It’s a bit like deciding that bat-chic is a better name for goth and then pumping out articles about the heady times, fashion and music of the 1980s bat-chic scene, while declaring it is absolutely 100% a thing that is coming back because some photos have been doing the rounds on socials.

Why has it taken such hold? (At the time of writing fresh articles are still appearing daily from major titles.) And why now? “I’ve looked at this in the context of music, film and fashion,” says Routledge. “And it’s around this age, late 30s and early 40s, that this generation gets the reins of power over culture. What I mean by that is: who’s calling the shots at the film studio, who is the editor of the magazine? That’s when these people are in charge. Obviously they’re not in charge of the bottom up organic cultural movement but they’re in charge of the discussion of it. So I think that’s part of the cycle – who gets to decide what gets the green light.”

Indie sleaze is also now apparently a film genre that existed 20 years ago too, according to Vulture, and includes such hard hitting, sleaze-ridden, depraved titles as Zach Braff’s Garden State. “Indie-sleaze cinema is characterised by gorgeous film sequences, manic pixie dream girls, and unabashed quirkiness” apparently.

Garden State (2004). Photo from Fox Searchlight Pictures

Obviously this whole thing is ridiculous and seems to be little more than an exercise in SEO. Which is fine as fashion and trends are supposed to be ridiculous from time-to-time, and the era of so-called indie sleaze certainly was. Whatever happens in the fashion world with indie sleaze (and I’m sure it will continue to be a thing while the right people are claiming it is a thing) remains separate to the discussion in question here because you can’t consciously replicate a youth culture movement, even if you want to. They are, in essence, born from the very pure and potent power of naivety. “When it happens more organically it is different from trying to explicitly recapture it,” Routledge says. “But what might happen is they can’t recreate it but it could serve some psychological function to just have that space and it might generate some other ideas.”

Interestingly, Routledge also suggests that a firm anchoring to the past is actually healthy for meaningful cultural progression and evolution. “There’s a term called cultural continuity,” he says. “Unless you’re really really alternative, if you see something that’s too chaotic or out there then you don’t get it. The idea is that we want stability, some connection between the past and the present. That actually helps us move forward because if there’s too much uncertainty or anxiety, or people have no idea what any of this stuff means, it’s hard to get people to be open-minded.

"They become defensive and they’re like, ‘this doesn’t make sense to me’. That shuts people down in terms of being open. Humans are security-oriented, as well as explorative and growth-oriented and when we get too out there and it feels unsafe, we run back to safety. But we’re also novelty seeking, there’s no progress if we just do the same thing over and over.”

Despite my deep cynicism and bafflement about all of this, made all the more apparent by the calm reasoning of Dr Routledge, many good things did come from this period. And even though very little of the music holds up, for me, I had a riot. Kids up and down the country were active in setting up club nights, gigs and labels, while the overlap of electronic and guitar music was – as desperately simple as it sounds – revelatory for a lot of people. It bridged opposing scenes and created a scrappy yet unified crowd. It was a time that was simultaneously daft and pretentious, messy, hedonistic, and a lot of fun. But times change, tastes change, thank god fashions change, and, crucially, music changes. You can’t bring something back to life by staring at old photos.