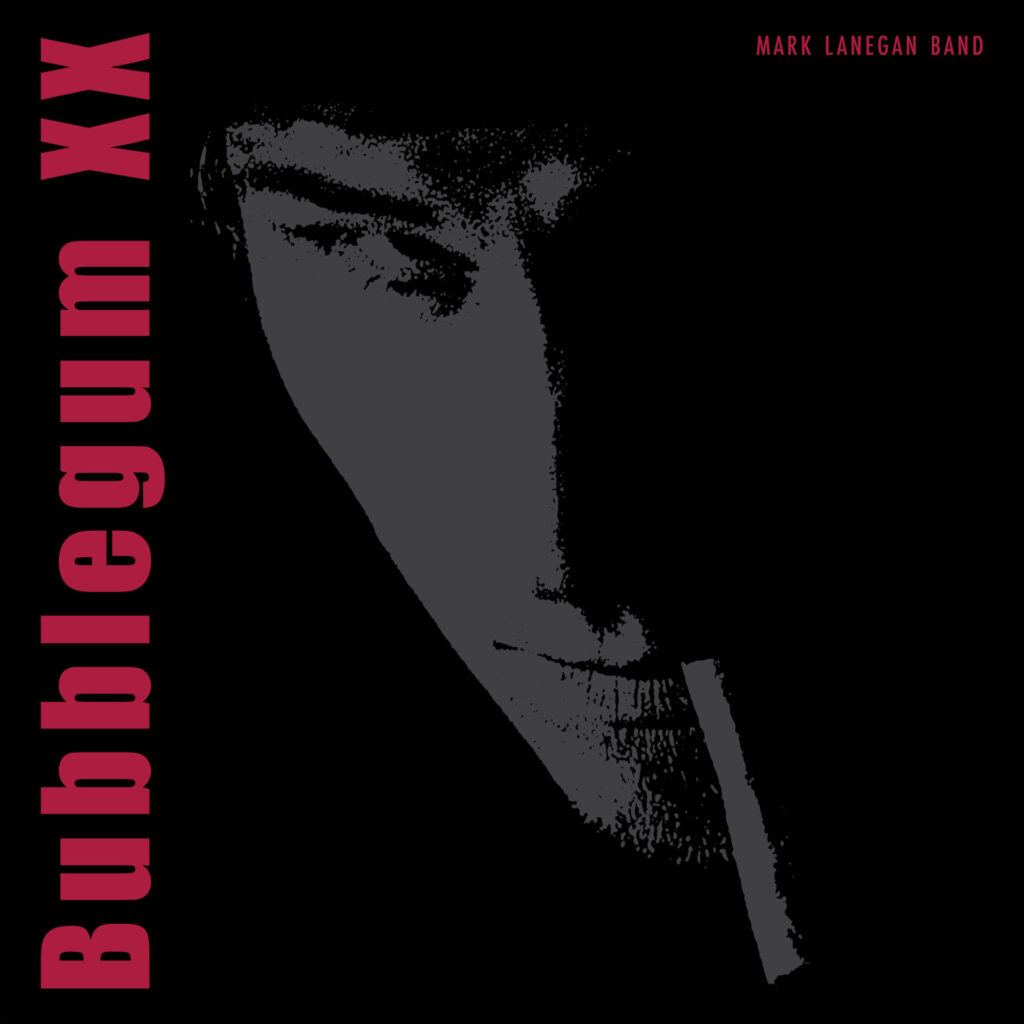

Back in the summer of 2004, Mark Lanegan’s Bubblegum seemed like the latest raid of an insurgency rather than its last stand. The former Screaming Trees vocalist, his friends Queens Of The Stone Age, along with Masters Of Reality and Monster Magnet represented a reassertion of aggressive, scuzzed-up guitar rock whose post-stoner rock – like the new wavier Strokes/ White Stripes/ Libertines axis – offered gritty resistance to the chart cleanup of stadium indie and reality TV pop, as the latter even colonised the term that had once just meant ‘popular music’. Yet QOTSA’s splendid, Lanegan-cowritten ‘No One Knows’ was a British top twenty hit in 2002, and Lanegan was all over QOTSA’s commercial breakthrough Songs For The Deaf (top ten in Britan; top twenty in the States). Kindred spirit PJ Harvey, meanwhile, chose to follow Stories From The City’s success by joining the QOTSA gang for 2003’s Desert Sessions 9 and 10, by singing on Bubblegum, and by issuing her own stripped-down, skuzzed-up Uh Huh Her that spring. Bubblegum’s title could be taken as ironic, therefore: the embodiment of ‘rock’ as something that could still scare children, Lanagan was an unlikely bubblegum pop purveyor. But it’s really a rebuttal, demonstrating that popular music can be commercial without being contrived, glamourous without being glitzy, and intricate without sounding sterile.

While its unifying sonic thread is a gothic desert shimmer, Bubblegum stretches to encompass a broad range of popular music – and not just the country and blues Lanegan reshaped in his skeletal image (influencing his friend Kurt Cobain along the way), the extras here including a cover of Johnny Cash’s ‘You Wild Colorado’ while ‘Wedding Dress’ quotes Cash and June Carter’s ‘Jackson’. There’s also space here for art-rock (a cover of Beefheart’s ‘Clear Spot’ on the accompanying Here Comes That Weird Chill EP), electronica (Suicide-al drum machines rattle throughout) and even hip-hop (‘Methamphetamine Blues’ is inspired by 2Pac and Dre’s ‘California Love’). Moreover, despite its defiant rawness, the album is very much produced: it takes studio hours to make a drum machine sound like a crashing garbage can as ‘Methamphetamine’ does. Similarly, the noises on ‘Wedding Dress’ are as hard to relate to conventional instruments as the lyric – sung with Lanegan’s actual wife, Wendy Rae Fowler – is to conventional romance: “The end could be soon/ We’d better rent a room so you can love me”.

The album stretches not just restrictive notions of ‘rock’, however, but the newly narrowed parameters of ‘pop’. What’s joyful about ‘Hit The City’, Lanegan’s duet with PJ Harvey is the way it revels in its own trashiness, its dumb-ass four-chord surge as pop as The Trashmen’s ‘Surfin’ Bird’ or Question Mark And The Mysterians’ ‘96 Tears’, the devalued and debased outlasting and outsmarting the elite and wholesome. Despite lyrics like “Ghost arrives at its bitter end/ To the promised land and the dark descends”, the song’s effect is life-affirming: “I couldn’t kill it!” the diabolic pair howl repeatedly, Harvey’s vocal distorted to fuck. Another garage throwaway, ‘Sideways In Reverse’ is all Stooges pummel and thrash, but as peppy as Bowie’s ‘Hang Onto Yourself’, so it sounds just dandy twenty years on. From its title to its topline of feedback howls, ‘Driving Death Valley Blues’ is desert-gothic garage-rock, this time underpinned by a European motorik (and lest we forget, ‘Autobahn’ was a transatlantic pop hit).

Bubblegum’s other unifying factor is Lanegan’s voice, a sound not just whiskey-soaked and oak-aged but age-old, its youthful frequencies (and illusions) stripped out. If you’re wondering where Lanegan left them (the frequencies, not the illusions), check out 1990’s fine solo debut, The Winding Sheet, which also reveals that for all Lanegan’s accredited folkiness, the scuzz was never far from the surface. Fact is, Lanegan doesn’t really have a surface: his gruffly yearning vocal renders ‘One Hundred Days’ both freshly perceived and mythically perpetual, with Dave Catching’s meandering, hazy spaghetti western guitar lines and producer Chris Goss’s almost subliminal, bottom-of-well piano plashes giving the track an epic grandeur that’s also grittily immediate. As a long-term drug abuser, the album-opening account of a near-death experience, ‘When Your Number Isn’t Up’, is virtually Lanegan’s theme-tune: that it took so long for his number to come up was as miraculous as much of this music. The “frozen border” Lanegan stays so close to that he “could hit it with a stone” takes Nico’s gothic heroin dreamscape but warms it with a slacker idyll-ness. There’s vulnerability rather than vainglory in the lyric – “they left you … to janitor the emptiness” (Nico’s vocabulary again) – along with self-mockery, Lanegan following up with, “So let’s get it on”: Nico’s death-mask would freeze in response, but Marvin Gaye’s would surely melt. The other Harvey duet, ‘Come To Me’ is the pole of ‘Hit The City’, a tender ballad, Lanegan almost crooning, Harvey virtually whispering – and while their voices combine on “Time takes a while/ To break you”, the narrative’s lovers never do. “Through my mind’s every riot or revelation/ You’ve just now gone/ As I arrive at every station” Lanegan laments, matter of factly. As the pair’s voices separate, Harvey first echoes Lanegan, then is left entirely on her own, yet rather than a paean to polarity, the song is a carol to connection. Indeed ‘Strange Religion’ hymns a redemptive relationship like Johnny and June’s: “Almost called it a day so many times/ Didn’t know what it felt like to be alive/ Til you been a friend to me”. That hard-won warmth is underpinned by the music, its arpeggiated guitar figure and organ shimmer inspired by ZZ Top’s 1972 ‘Sure Got Cold When The Rain Fell’, with both tracks highlighting how much soul there is amid the ‘whiteness’ of classic rock. With the song’s gospel choir tipping a hat to Guns N’ Roses’ ‘November Rain’ (1992), the presence Izzy Stradlin and Duff McKagan on backing vocals makes perfect sense.

While there’s great stuff on this reissue’s extras, they only really reinforce the near perfection of Bubblegum itself, its coherence as a sonic and sentimental statement. Yet the album underperformed commercially, and pop would soon become all-conquering, colonising stadium indie to produce the Funs, Bastilles and Imagine Dragons in Coldplay’s polite image. While the White Stripes and Strokes would still chart high, their sales dropped off, as did QOTSA’s, while like the Libertines, drugs caused their well-drilled desert gang to disperse. Like Harvey, Lanegan wouldn’t release another guitar-based album for eight years. He would never top Bubblegum, which stands as a testament not just to Lanegan’s talent but to the potency of the power-chord, the pleasures of sonic dirt, and – for all its druggy doominess – the undersold affirmation of aggression in popular music. They couldn’t kill it.