The verb ‘to chitter’ has gone through a reversal of fortunes. Once falling between the ornithological stools of chirp and twitter, meaning a series of high pitched sounds like bird call, its stock has risen in recent years. Whether its ascendency was caused by a growing dislike of the word twitter can’t be proven but it maps at least. But if the term has been rescued from lexical obscurity, this is perhaps because it has become the captioner’s preferred nomenclature for the sound emitted not just by birds but by nearly all non-humanoid, non-verbal monsters, aliens, demons and abnormally large insects portrayed on screen over the last two decades.

When he was a kid, veteran voice actor Peter Cullen, saw a horseshoe crab on its back, baking in the sun on a beach, emitting a crackling, bubbling… chittering sound. And he drew on this experience when creating the voice of the Predator for the 1987 film of the same name. We have come a long way in terms of sound manipulation since then, but the creation of such a perfect alien-sounding voice seems to have acted as a colossal block to creativity in most quarters. It’s almost as if we all now ‘know’ what an extraterrestrial would sound like, and that any suggestion to the contrary is a consensus shattering irritant.

One of the few recent examples of sci-fi or horror for the screen to acknowledge the chitter but to also imagine a sonic field beyond it – and therefore beyond cliche – while making full use of the tools currently available, is the animated drama Scavengers Reign. The sounds here range from squelchy wetness to arid crackle, from the familiar to the alien, from the plausible to the fantastical; the range and ingenuity matching the inventiveness of the alien creatures on show themselves. Some of the indigenous fauna of the planet Vesta emit noises that sound uncannily like music to the stranded crew of the Demeter 227 and these sounds often gel or clash diegetically with the actual synth-led soundtrack in surprising or pleasing ways, creating a soundscape which is an analog of IDM or ambient music, underscoring the idea that a great deal of effort has been put into sidestepping convention and creating something that stands apart.

The endlessly adaptable drummer/percussionist Valentina Magaletti and Amsterdam based sonic sculptor of post dubstep electronic music Upsammy, on the strength of their incredible set at Manggha, are both very aware of and ultimately unconcerned with the “colossal blocks” that litter the path of people making live dance music in 2024. The pair met last year while working on the Breathe, Walk, Die sound installation for the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and the recordings they made then form the basis for tonight’s performance. These sounds are processed live by Upsammy via a complex FX chain, in tandem with hardware synths and sequencers via a DAW, while Magaletti switches her attention between her kit and a vibraphone, using atypically placed contact mics to maximise her potential.

The sound opens with a Predator-like chittering. Time-stretched samples purr as they elasticate; rough grains appear as noise is pulled apart; complex wave-folding creates audio forms that would appear so bizarre on an oscilloscope as to look dangerous; sharp electronic clicks wax and wane temporally. But this, layer by layer, is an act of world building. A sound environment that references audio history while gleefully building something new. (My guess is) samples are matched with sounds created by physical modelling hardware; essentially synthesisers that shape noise by ‘exciting’ or ‘striking’ non-existent – i.e. modelled – blocks, tubes or strings to produce a number of surprisingly real-sounding wood and metal sounds. Both of these sources then get warped into hyperreal new sonic events, while the real time hits emanating from Magaletti’s kit – due to the use of those contact mics – often sound like the product of soft synthesis. The point being: you can’t necessarily tell who is doing what.

The shift from chittering / physical modelling into something that sounds like musique concrète is smooth, but this is a collage of sounds that slowly begins to take form in the sense of rhythm. Can you have concrète that slaps hard? This is the way that this is progressing. Instruments such as the marimba, vibraphone, Burmese gong and koto, especially used to create a rhythmical but othered environment, may trigger a negative association with exotica for some, but this is several stages removed. Not so much fourth world as the fourth world orbiting a very different sun to our own. Things resolve – very satisfyingly – in a form that’s recognisably drum & bass but where literally every sound is novel.

Multiple creative uses for, strategies against, accommodations with and evolutions of noise, are the structural beams which support this year’s Unsound festival, which is held across eight nights in numerous venues in Krakow. The reach of organisers remains impressive and – for those who find the idea of over a week’s worth of harsh noise, power electronics and lectures on Jacques Attali a little distressing – the theme is interpreted in a number of surprising and entertaining ways, although the always engaging Robin Fox does present a personal / autobiographical take on Attali’s Noise: The Political Economy Of Music. And it’s not like noise music is ignored altogether.

Coming of age in the 1980s when it was relatively difficult to find useful information about obscure musical subgenres, I convinced myself that noise was made solely by angry and antisocial art students who had pummelled themselves into the arms of fascism via amphetamine psychosis, and it wasn’t until meeting Wolf Eyes about 21 years ago that I had any reason to challenge my own ignorance. While playing ATP the trio granted me an interview for a feature that was eventually spiked because they spent the entire time watching a Manowar DVD, wearing Manowar T-shirts, drinking whiskey out of Manowar mugs, claiming it was band policy to only talk about Manowar. “We admire their work ethic”, was one statement I remember clearly. So I did learn one important lesson: political philosophy is never hard coded into any genre of music.

Yellow Swans are neither antisocial speed-addicts prodding their audience’s hypertrophied outrage glands or the (genuinely brilliant) Beastie Boys of noise, but instead, seemingly genial, mellow with middle age, bearers of the spirit of Paris 68, optimistically still in touch with the idea that change is possible. Their opening gambit references American situationist group the Yippies and their pranksterish ‘threat’ to levitate the Pentagon in 1967, suggesting that we still need to finish what they couldn’t and to keep raising the US Department of Defence until unmoored from terra firma and in a position from where it can be flung into the Sun. Just in case we haven’t yet got the message, their first track is the entire 1959 Big Table, Chicago, recital of ‘Howl’ by Allen Ginsberg, dragged slowly into echo, static and chaos as Gabriel Saloman and Pete Swanson groove away either side of their table full of boxes. Of course, it’s not just noise. Ragged, reverberant melody shines through the scree and choking dust, like rays of coruscating sunlight piercing the atmosphere above a recently bombed city. And of course it’s especially important at the moment that some hope and some beauty persevere. It’s also interesting to note how, this week at least, Egyptian electronic producer ZULI occupies similar ground, although he, presumably, uses very different methods to get there.

Sometimes it’s hard to locate the idea of noise in the practice of the artists here. It takes some time to work out that Catalan vocal duo Tarta Relena, who are presented as representing the ‘noise’ of competing national cultures, folk styles, the clash of history, the secular and the sacred, is something of a red herring. It’s only during a stunning rendition of ‘Crit Premonitori’, the climax of their excellent new album, És pregunta, it comes slowly into focus as a circular phrase, sung with struck crystal-like clarity, is slowly encroached on from all sides by digital distortion and tape noise before cutting off into silence like a guillotine, just as it starts to become unbearably tense. The song’s title, Catalonian for ‘foreboding cry’, can’t help but make me think of Attali and the double edged sword of weird – in the original prognosticatory sense – music as both a space in which a better future can be imagined and a warning of what awful things may yet come to pass.

The impact of 4’33” on popular culture is something of a curse, I feel. I’m now never not aware of audience noise in an orchestral setting, as if it was deep programming by the experience of John Cage’s piece itself which has forced every cough, splutter, ringtone, scraped chair and conversation into an act of violent misophonia. Despite unnecessary competing noise, Mica Levi’s collaboration with the Sinfonietta Cracovia, is a success, bringing to vivid life a non-film orchestral composition from four years ago, ‘Thoughts Are Born’ another from five years ago ‘Flag’ and three other pieces commissioned by Unsound. There is a sizeable stir in the venue, as Levi swaggers on stage at the end to shake hands with people like someone who’s just sold a second hand jag at a tidy profit, rather than one of the most exciting composers at large today taking a bow; and just for a second it occurs that if they’d been sat on stage the whole time, perhaps people would have thought twice about even shifting in their seats let alone indulging in chittering.

Outrage at the noise around us, plus misophonia, tinnitus, hyperacusis and the numerous strategies we employ to cope with the unwanted noise of modern life are subjects very much at the forefront of an excellent presentation by sound researcher Mack Hagood called The End Of Listening, drawn from research for a recent book Hush: Media And Sonic Self-Control.

Amar Bose, the inventor of noise cancelling headphones, probably didn’t foresee the total granular curation of the entire sonic environment in real time as the endgame when he first conceived of an audio device that would separate wanted from unwanted noise while trying to listen to music on headphones on a commercial jet in the late 1970s. But this is certainly what is offered by the technology of wearables, which are already in the prototype stage now. The next step on from active noise cancellation headphones, wearables are discreet in-ear devices which are already powerful enough to filter out dog noise but not cat noise, for example. But why stop there? The safety implications of wearables that filter out traffic noise but not music are disconcerting; the moral implications of wearables that filter out voices based on variables such as gender, race, accent and pronunciation are terrifying. That noise cancelling headphones might be a new battlefront in an aggressive new form of interpersonal cancel culture barely bears thinking about. Hagood references Orpheus indulging in an act of existential noise cancellation while on the Argo to protect Jason and the Argonauts: he belts out a ballad to protect the Greeks from the pernicious song of the Sirens. This is the basis for his idea of Orphic mediation for dealing with contemporary noise, tactics drawn upon in order to “pursue what feels enlivening and enabling and… to avoid what makes us feel diminished and disabled”. So not just cancellation but also masking, for example, with white and brown noise generators being used as a coping method by those with tinnitus and ADHD, which is fair enough, but as regards the totally curated audio environment he asks pointedly: “Is hearing what we want really the future we want?”

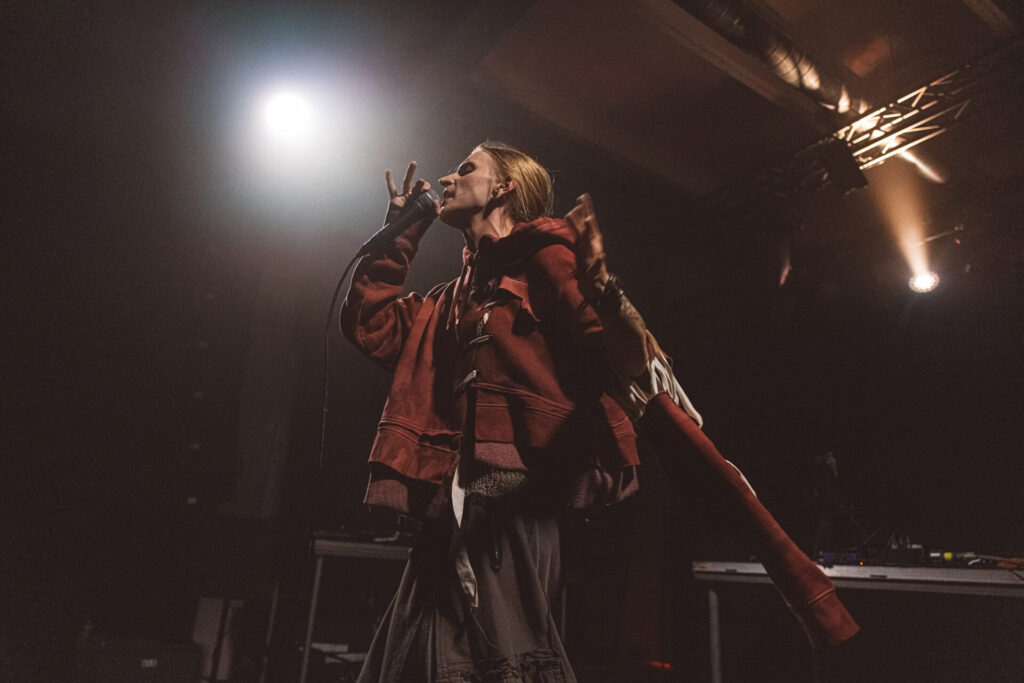

It’s interesting to see two of the most exciting British musicians of the last ten years playing one after another, albeit on different stages, given that they are both travelling from dissimilar origin points towards a more centralised but still very wide, and under explored zone. Dance music producer AYA never presents anything less than an incredibly entertaining performance and quite often delivers something that is sonically surprising, unique and full of serotonin-burst elation as well. Tonight, performing live rather than DJing, an ever more academic distinction, especially for someone who likes to jump on the mic so much, there is an unmissable sense of sadness, heaviness and anxiety however, as elements of digital black metal, the fracturing electronic noise of Pan Sonic and the analog reverberant drone of KTL, intrude forcefully into proceedings. It’s no one’s business but hers but one would hope the tonal shift is solely an aesthetic decision. The slamming Petronn Sphene, who goes by a bewildering array of names to match her bewildering array of projects which include (but is by no means limited to) Guttersnipe, Tristwch y Fenywod and The Ephemeron Loop. Petronn Sphene, is a one woman deconstructed gabber/exploded hardcore project, or “no wave rave” as she terms it herself. Playing a drum machine and synth live simultaneously allows nerve shredding control of tempo, with every MPC1000 kick, every rave hoover stab, every acid squelch and every eye-blink snare, placed to system-jangling effect, with the vocals themselves adding a glossolaliac terror to an already harrowing alien xenoglossy. I’m not going to lie; it’s a baptism of fire, even if you’ve seen her do this before, which I have, but something counterintuitive eventually happens on full exposure to the Petronn Sphene method. Submersion/submission acts like anxiety cancelling headphones for the psyche. While some punters bail for easier to process sounds to be found elsewhere, the percentage of those who stay the course achieving a juddering, id-scrambling epiphany is clearly very high. I don’t know that either of these artists would necessarily think of themselves as doing anything similar, but seeing them one after another was a rare treat for me at least.

There are more highlights across the week than I have time to mention but in purely experiential terms, The Body and Dis Fig bring a gorgeous level of drone, tactile bass, industrial noise and insistent but still luxurious vocal presence that is hard to top; and Kenyan digital grindcore MC Lord Spikeheart delivers a show so amped up in energy, that delivers so fulsomely on its promise, that it ranks as one of the top metal shows I’ve ever seen, and even outstrips exciting early Duma and Scotch Rolex gigs. I’m well into my sixth decade and believe me, I grew tired of wall of death and circle pit shenanigans in the late nineteen hundreds but fair play to Spikeheart for not stopping until every single person in the room is totally energised and engaged by this mad mix of splattercore, goregrind, death metal, industrial techno and dancehall, egged on by his irresistible hypemanship. Everytime I feel my energy beginning to flag I catch him shouting something mad like, “Gandalf – where are you?!” and it’s on again. For me, the week ends on an unbelievable high. There is a select group of songs that hit it so right that I feel like I wouldn’t mind if I died as they faded out. And because I’m quite staunchly opposed to death in general and me dying in particular, I mean this in a very positive way. ‘Moonage Daydream’ by David Bowie. ‘California Soul’ by Marlena Shaw. ‘Uncertain Smile’, album version of course, by The The. ‘That’s How I Feel’ by Sun Ra. There aren’t that many of them. But I realise now that I’ve finally seen them live, this is how Lankum make me feel, especially on the epic trek from ‘Fugue’ to ‘Bear Creek’. But also that ‘Go Dig My Grave’ has been my most sung song for well over a year now. Which all goes to say I think they’re a very special band and I love what they do very much indeed. Well done Unsound, whose righteous noise to signal ratio remains an example to most.