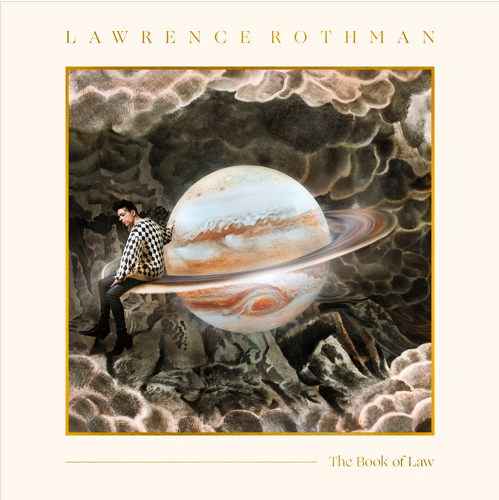

Three years after the first man landed on the moon, David Bowie appeared as Ziggy Stardust on BBC’s Top Of The Pops in January, 1972. For Bowie, the notion that something much larger than Earth existed was ultimately subversive. The contrivances and conservatism of the planet, which had once seemed absolute, were now uncertain. In other words – space threatened to queer Earth. It’s no coincidence that the skyward Stardust was bisexual and a formerly ‘heterosexual’. Elton John was quaking in his moonboots. While Ziggy accepted his fate in space, on ‘Rocket Man’ Elton John was struck down by gravity: "I miss the Earth so much/I miss my wife", he once said, heterosexually. Just less than half a century later, Lawrence Rothman is pictured squatting on Saturn, on the cover of their debut album The Book Of Law.

Like Bowie and Prince, icons appear like aliens – they are never part of a group. Rothman’s voice is as distinct as any icon and alien, and that is the exact goal of this debut – to be iconic. It’s clear that Rothman’s ambition is to reach the heights of former queer stardom – an all-star cast enlisted to make The Book Of Law something remarkable. It’s produced by the famously histrionic Justin Raisen (Charli XCX, Sky Ferreira, Angel Olsen), with Bowie’s director Floria Sigismondi in charge of the noirish music videos. Kim Gordon, Angel Olsen, Marissa Nadler, Duff McKagan feature because they appeared to Rothman in a dream, and because Raisen managed to rope them in.

Angel Olsen lends herself to one of the album’s strongest moments. Her shrill voice accessorises Rothman’s baritone superbly, as they queer the male-female vocal duet in ‘California Paranoia’. It’s one of the only songs on the album to embody a singular queer glory, instead of recreating it from the past. There is currently a happy abundance of genderfluid stars who are championing the new sounds of futurism. Rothman, however, is part of a small group who are using the musical traditions of the queer past to enforce their own identity.

Ziggy Stardust, as already mentioned, and Prince’s Camille relied on an alter-ego to access the private fantasy of queerness. Today, Rothman’s queerness hardly exists as a coherent identity, but rather as a set of splintered selves. Rothman refers to them as ‘alters’ and there are nine in total; each seem to pastiche different queer musical traditions. Opener ‘Descend’ is a silky take on the glam piano tradition; ‘Wolves Still Cry’ and the next few songs bear the tiny teeth of a funk guitar; ‘Jordan’ through to the album’s finale soar, ‘Ain’t Afraid of Dying’, has the gusto of a power ballad. There’s hardly any distinction between each ‘alter’, but it’s interesting to hear the development of Rothman’s baritone throughout the album. They begin very close-throated, with what sounds like an extra glottal impersonation of Rick Astley, and concludes the album with some husk but without strain on ‘Ain’t Afraid Of Dying’.

Rothman’s queerness is encoded more artfully in their vision than their sound. The music videos serve as the perfect introduction to their nine ‘alters’, while the album itself falls short. The ambition is admirable, but what makes the songs commendable is their refusal to thrive. They are deeply melancholic. There’s a focus on Rothman’s drug addiction itself rather than the desire to resolve it, a resignation to dying rather than a desire to learn how to live.

While they perhaps too ambitiously place themselves among their queer forebears, Rothman does stand apart from their contemporaries. This album is a window into the destruction that occurs when someone is told that their identity is illegitimate. While there are plenty of queer musicians today who encourage the community to be resilient, Rothman lets us know that it’s okay not to thrive. After all, when most of the world is against you, life can be very tiring.