It’s a point I’ve made often in this column, but once again for those at the back: there is really no such thing as a folk ‘revival’. The term implies a cycle of death and rebirth, where in reality folk music is a constant thing, albeit constantly shifting – like that old idea of a river as both permanent in status and ever-changing in make-up. In England, traditional music and culture is currently receiving greater attention than normal – perhaps by chance, or perhaps as a response to a feeling that in such unstable times we’re seeking something ancient to cling to as the ground we once knew is shifting under our feet. But that’s all it really is – attention. When the zeitgeist’s eye swings elsewhere, Sauron-like, there will still be those continuing to push things forwards under a less intense glare.

Such thoughts come to me at King’s Place in London, as I watch Eliza Carthy kick off the venue’s April Folk Weekend. She is, of course, the daughter of two bona fide giants, Martin Carthy and Norma Waterson – who made their names during one of folk’s previous moments in the sun – and has been performing alongside family members, and in projects of her own, since childhood. Having turned professional as a teenager, Carthy has seen attention come and go, not only for her work, but her family’s too.

Her father Martin, for instance, is currently undergoing something of a renaissance. Lauded as a hero by many of the scene’s rising young musicians, he has performed and spoken alongside many of them at the London scene’s central Broadside Hacks Folk Club. A few days before the publication of this column, father and daughter will have travelled to St. Louis, Missouri, to play a festival show for a folk club Martin once performed for 60 years ago. Later this month, Martin releases his first studio album in 21 years, backed largely by enthusiastic crowdfunders, on which he revisits material first recorded on his self-titled debut LP in 1965. It wasn’t always this way, however.

“For the longest time, I think he felt ignored. He felt that everybody was happy to talk about Bert Jansch, Davey Graham and John Martyn, but that people had forgotten about him,” Eliza tells me over the phone the day before the King’s Place gig, procrastinating while packing. “But the new generation that has discovered his work, like Goblin Band [whose performance of the Martin Carthy fixture ‘Willie’s Lady’ has brought plaudits from the man himself] and Broadside Hacks, the way they’ve embraced him in a way that has included him, it’s been beautiful to watch.” Her late mother Norma Waterson had also felt “very, very low” about a perceived lack of recognition in her later years, Eliza says – although the overwhelming response to crowdfunding efforts to counter a pandemic-induced collapse of their income “definitely helped her to understand that people did still hold them both in high regard”, shortly before her death in 2022.

Eliza, too, has been buffeted around plenty during her career. She recalls a “manufactured beef” in sections of the press between her the musician Kate Rusby – based mainly around the fact they both played folk and were both young women. “It’s kind of fun, the ‘Blur and Oasis of folk’ thing,” she laughs, “but ultimately we always occupied our own space.” Wider attention for her solo work has flowed – both 1998’s Red Rice and 2002’s Anglicana were nominated for the Mercury Prize – and it has ebbed; she also recalls the considerable attention she and her parents received for their debut album together as Waterson:Carthy, and the distinct lack thereof for follow-ups.

“I think I did feel frustrated at one point,” she admits, but today comes across as zen. She’s turning 50 soon, and working on a rock album, “which is something that’s much more accepted now than it would have been 25 years ago,” she argues. “When I was 25 I was worrying I was getting over the hill! But now I’m really excited about the next phase. I can get up on stage at the Royal Albert Hall for Richard Thompson’s 70th birthday party, and I can go onstage at Brighton Komedia and play silly rock music with my band and jump up and down. When I was younger, if I did something outside of traditional music [folk fans] might think I was selling out, or trying to be something I’m not, but now people know that I see everything as part of a whole – that it’s always been about the conversation; how traditional music marries with contemporary music; and how it reflects modern life as much as it reflects the life that people lived in the past, universal human concerns.”

Watching Carthy onstage at King’s Place, you feel that sense of liberty in her role, allowing her to skip effortlessly between different modes. At times she’s the born entertainer – a little ringmaster’s flourish of accordion at the end of ‘Three Drunken Maids’; a breakdown of sex in folksong via a wonderfully daft ‘naked sock puppet theatre’ – and at others she rests heavily on pure emotion, as with the music hall number ‘Pulling Hard Against The Stream’, a song that longs for kindness in a world where it’s lacking, and that Carthy tells us her mother used to sing with her sister Lal Waterson before the latter’s death from cancer aged just 55, after which Eliza took her place. During the interval, she tells us at the start of the second half, one crowd member was telling her about his love of a particular song in her repertoire, ‘Worcester City’, so she dedicates it to him and his daughter. Then there are moments of straight-up musical showboating. Though mostly a set of unaccompanied singing (where her voice is rich and soulful), when she does pick up an instrument it’s often dazzling – the sheer intensity she coaxes from the fiddle on ‘May Morning’, for instance. To close, she ventures outside of folk music’s supposed parameters entirely with an uplifting rendition of ‘I Used To Be Color Blind’, from the 1930s Fred and Ginger vehicle Carefree.

What shines through most of all in Carthy’s live performance, though, is its mischievous sense of irreverence, not least for the wider King’s Place programming. The folk weekend is themed around birdsong, but by the start of the second half, Carthy admits, “I think I might have run out of bird stuff.” When even the slightest avian reference does appear, she’ll frantically point it out, like a student trying to blag her way through a hastily written presentation.

That irreverence, and disregard for arbitrary boundaries (who’s to say that ‘…Color Blind’ can’t be a folk song?) might at first seem at odds with Carthy’s parallel role at the heart of the English folk establishment; in 2021 she was appointed president of the English Folk Dance And Song Society, following 13 years as vice president under Shirley Collins, an organisation that traces its roots back to the Victorian era. It is, however, central to that role too. “I like being the poster person,” she says, in the same way she likes “the fact that I could be singing a Lancashire clog dance with Jennifer Reid one minute, then singing with Robert Plant the next – that’s what traditional music is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be in the fabric of society, not locked away in some musty little chamber somewhere. I’m still as passionate about this stuff as I was when I was 16, I was on a mission then and I’m on a mission now, and that very much aligns with the way the EFDSS wants to be at the moment.” (A week or so after our conversation, the society issues an unequivocal statement reaffirming their solidarity with trans and non-binary communities in the wake of the UK Supreme Court ruling on the legal definition of sex and gender). “They want a president who’s going to speak out, so I get my hands dirty on social media, you know?”

Here, it’s worth highlighting just how much Carthy walks the walk. A firm believer in English folk traditions as a place where diversity of race, gender and sexuality can be embraced, she’s unafraid to get stuck in with those who feel differently. I remind her of one such occasion, where she rebuffed each and every person who took part in a coordinated racist and homophobic pile-on against an article celebrating increased diversity in the British folk scene – how impressive I found her sheer bloody-minded stamina. “I’ve just been doing something similar with a load of bloody mouth breathers at the Daily Express, talking about [Lancastrian clog dancing group] the Britannia Coconut Dancers still refusing to ditch the blackface when they dance. Loads of the gammonati came out going, ‘You’re messing with our traditions.’ First of all, no one’s messing with your traditions, and second, I don’t think any of those people would know what a British tradition was if it bit them in the arse. There are plenty of Black Morris dancers in this country, Muslim Morris dancers, dancers from every walk of life, every religion and every creed. So don’t even start with the ‘if you don’t like it go back to where you came from’ shit. Folk music does not claim those people. We refuse.”

Eliza Carthy has just released a new EP of solo recordings called No Wasted Land, which you can find on Bandcamp here. Her latest original album is Through That Sound (My Secret Was Made Known), and was released last November.

Martin Carthy’s new album Transform Me Then Into A Fish is released on May 21. Find out more by clicking here.

VaroThe World That I KnewSelf-Released

Lucie Azconaga and Consuelo Nerea Breschi are French and Italian respectively, and take their name from a river that was once considered the official border between the two countries – but have become fixtures of Ireland’s traditional scene since meeting in Dublin in 2015, where they bonded over the shared love of the country’s music that had prompted both to make the move there. For a measure of just how much they’ve been embraced since, it’s worth taking stock of the names that feature on this long-in-the-making collaborative record The World That I Knew; Lankum’s Cormac Mac Diarmada and Ian Lynch appear separately across the record, as do John Francis Flynn, Niamh Bury, Junior Brother and many others.

Yes, it’s a who’s who, but that in itself isn’t what makes The World That I Knew so great. Rather, it’s what Varo coax out of their collaborators that counts – the way that Azconaga and Breschi’s own playing and singing interweaves with that of their collaborators. They know when to fall back and provide a platform – as on the genuinely sublime ‘Red Robin’, where Alanna Thornburgh’s harp is let loose to construct a gorgeous melody – and when to move in tandem full-throttle with their guest; regular listeners to Flynn’s solo albums will recognise the haunting tin whistle that opens ‘Green Grows The Laurel’ as something of a calling card, but what follows is an elegant duet, Varo’s vocals, gentle plucks of viola strings and a subtle drive of piano and hammond organ.

Running the gamut from bold a capella (‘Open The Door’, with Anna Mieke) to miniature epics (‘Skibbereen’ with Junior Brother), it’s clear that there have been efforts to corral this diverse selection into a unified whole. It’s telling, for instance, that the record opens with an ode to the power of community and co-operation (‘Lovers And Friends’, with Mac Diarmada and Ruth Clinton), before going on to demonstrate that fact through repeated collaborations, and that it ends in a place of melancholy solitude as they draw to an end (‘Alone’, with Branwen and Slow Moving Clouds). It’s also notable how often themes of Ireland and Irishness arise in the songs’ lyrics – the figure exiled by famine and pining for home on ‘Skibbereen’; Lynch’s call for an “Ireland free from slavery” on his rendition of the radical 19th century song ‘Sweet Liberty. It might just be due to the Irishness of Varo’s collaborators, but nevertheless it feels notable that a record such as this should be helmed by two immigrants – proof, not that it’s needed, that folk music is at its best when left open to ‘outsiders’.

Trá PháidínAn 424 (Expanded)Hive Mind

Originally self-released on Bandcamp a few years ago, now extended with three extra tracks for a new vinyl version by Hive Mind records, Trá Pháidín’s An 424 is as much a work of psychogeography as it is of folk music. There are elements of trad in the instrumentation here – but they’re mixed into a swirl that has as much, if not more, in common with post rock, the absurdist avant garde and spiritual jazz. As I explored in the introductory essay to the last Radical Traditional, however, I consider anything that delves into the relationship between people and their surrounding environment to be well within this column’s realm.

The environment in question here is the 424 bus route in the band’s native Connemara – a coastal area where Irish remains most people’s first language. They cite Tim Robinson, who once walked the entirety of these ragged coastlines, scaled mountains and traversed bogs for an acclaimed trilogy of books exploring the region’s history, culture and folklore, as a spiritual predecessor, whose subject was the same dramatic environment that a 424 passenger will experience from themselves as they gaze absently out of the bus window. As the band themselves put it, “If you are someone who grew up or lives in this region, you have a particular understanding at this stage of how complicated Gaelic psyche is and the kind of spectrum of identity along bóthar Choise Fharraige [the road which the 424 travels down]. With the landscape in mind, this bus journey is a great meditation of the various topics of life.”

A 90-minute epic, this is a record of such depth that any analysis I might offer within the scope of this column – particularly as an outsider – would only scratch the surface. I would, however, like to point out just how utterly brilliant it all sounds – the wheezing of an opening bus door and drums that click like an indicator mingle with languid drifts of brass on opener ‘Cáin Chairr’, before the pace picks up with a magical pump of rhythm – as if our vehicle has suddenly shapeshifted into a magical vessel that’s hurtling toward another dimension. Moving through celestial abstraction, pulsating kosmische grooves and moments of eerie dissociation, their music transforms Connemara into a hallucinatory parallel version of itself, in which we see passengers like ‘fear liatroime’ (Leitrim man), ‘dhuine siúl sa hi-vis’ (‘yer man walking in the hi-vis’) and ‘yung fella’ appear and disappear like phantoms.

Ben McElroyElkwortlaaps

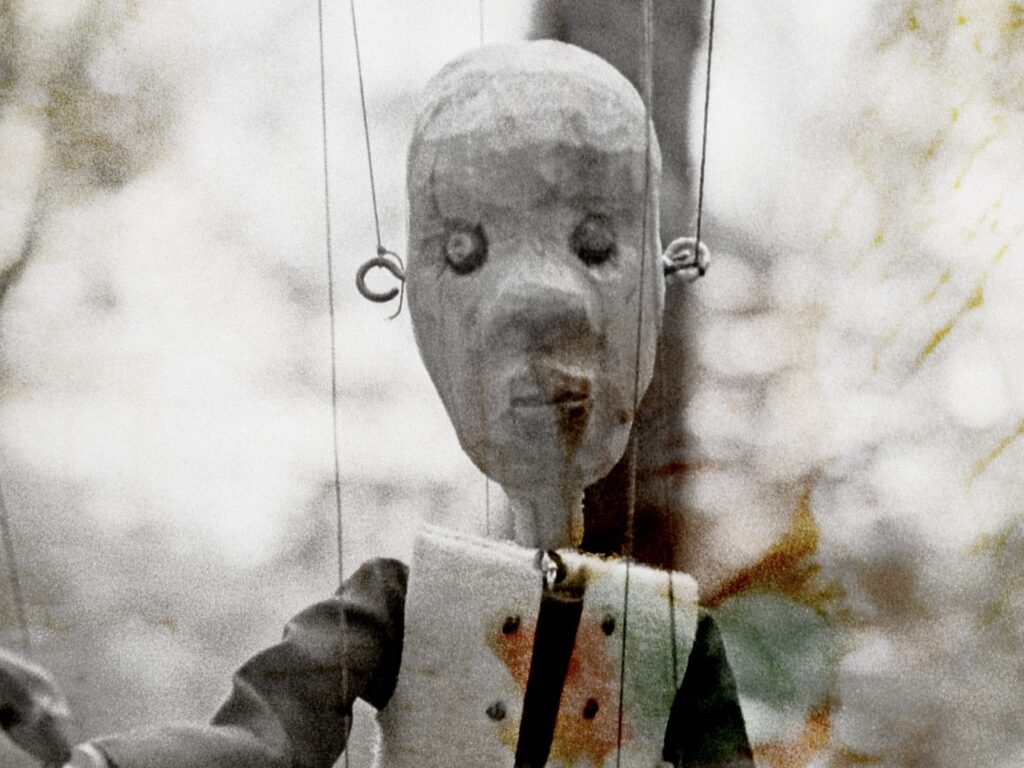

In the short film Widdershins & Deosil, squatted among the ferns in a patch of Derbyshire forest, we find Wirral-born musician Ben McElroy carving the primitive-looking head of a marionette from a hunk of wood. Widdershins – as the puppet is called – takes his name from an old word roughly meaning counterclockwise or lefthandwise, a direction that in British superstition was once considered highly unlucky (in the 19th century fairytale Childe Rowland, a girl called Burd Ellen runs widdershins round a church causing her to be imprisoned in Elfland). With that etymology in mind, as McElroy’s Widdershins dangles and stumbles alongside him through the forest, finding a companion named Deosil, and then losing her again, it’s hard not to be left feeling that sense of unease that comes with all the best folk-tales. The beauty of the accompanying music – elegant drones giving way to a shimmering guitar duet between McElroy and Nick Jonah Davis, and then to haunting vocals by the singer Debbie Armour (incidentally a member of a group also called Burd Ellen) – increases that fact through its juxtaposition with the visuals, although the whole thing is left dreamlike enough that concrete meaning is your own to impart.

The music in the film is a condensed version of McElroy’s excellent new album Elkwort – dissonant and beautiful sonic meditations that grew out of improvised pump organ and cello exercises that served a therapeutic purpose – allowing him to “gnaw into deep, old brain feelings,” as he puts it. As well as Davis and Armour, he brings in another guest, Welsh folklorist and multidisciplinary artist Elinor Rowlands, who provides buried spoken word as clarinet, cello, guitar, bass, drums, bodhran and pump organ tangle and knot together like the roots below a forest floor.

QuinieForefowk, Mind MeUpset The Rhythm

While developing her new record Forefowk, Mind Me the musician Quinie took a trip through Argyll in the West Scottish Highlands with her horse, Maisie. The slowness of such a journey, she says in the album’s press material, “opens up a whole new way of moving through the landscape. You pay attention to all your senses, have different conversatins with people and connect to older ways of doing things […] it clears your mind in a unique way.” Though born in Edinburgh, she tells tQ over email that she chose Argyll because it’s where Irish people first settled in Scotland in the 6th century, a fact that chimed with her own ancestry (she is from a second-generation Irish family). She sings in Scots, meanwhile, thanks to the influence of Scots traveller singer Sheila Stewart, who she first heard singing unaccompanied on the radio in 2015. Despite Quinie’s initial reservations given that she’s not a traveller herself, her deep love of the music, and arguments by traveller friends that a settled person sharing this music might raise wider awareness of it, saw the style become central to her practise. “Scots gives me a way of expressing myself which is connected directly with the landscapes I love. It brings the songs alive,” Quinie continues in the press material.

Listening to the record (Forefowk coming from the Scots for ‘the people who came before,’ or ‘ancestors’) is to hear that tight knot of connections to her surroundings made palpable. It’s in the way her singing emerges with such easy power on unaccompanied numbers like ‘Bonnie Udny’ and ‘Generations Of Change’, and how it weaves so effortlessly into the enveloping drone of pipes on songs like the resonant ‘Col My Love’, the brooding ‘Sae Slight A Thing’ and the frayed ‘Cam A Ye Fair’. It’s in the way her vocals skitter and dance in tandem with fiddle on the delightful ‘Macaphee Turn The Cattle’, over a ramshackle rhythm played on whatever her instrumentalists had to hand – including a cheese grater and a woodburning stove.

Mamer 马木尔Awlaⱪta / Afar 离Dusty Ballz

Mamer is best-known in the West for his 2009 album Eagle, which drew heavily from the traditional music of the Kazakh community in the autonomous Xinjiang region of China in which he was raised, and was released by Peter Gabriel’s Real World Records. Dissatisfied with its glossy production and the stereotypical ‘world music’ marketing, however, in the years since Mamer has been delving deeper and deeper into the avant-garde. In December 2021, at the Old Heaven bookstore in Shenzen, he arranged a residency of 14 gigs in 15 days, with ‘themes’ decided on at the last minute and audiences allowed in for free. The gigs were mostly brutal, drawing on the industrial music, drone and harsh noise he’d been exploring in the year’s since Eagle, apart, that is, from night five. Here, he made a U-turn, performing only with a nylon string guitar, and returning in minimal style to the music of his youth. It’s that set that’s captured on Awlaⱪta, the title coming from a Kazakh word that literally means “outside” or “elsewhere”, but that liner notes explain should be taken here to imply “a condition of sustained liminality, a voluntary exile of being a stranger in a strange land.”

Taking in everthing from a sprawling and warm rendition of ‘Love’, a 90s ballad by the Kazakhstani rock group Roksonaki which Mamer would have heard over the radio as a boy, to an ancient piece said to have been composed on the sıbızğı flute by the mythological Turkic hero Korkut Ata – presented here as a minimalist epic – to an elegant composition by the early 20th century master of the dombra, as well as original works, Awlakta could easily be viewed as a ‘back to the roots’ performance. And yet, it still feels in line with Mamer’s wider experimental practise. His sparkling, shimmering guitar-playing turns his old source material into something properly transcendent, in the same way Robbie Basho’s did with American Primitive, or Carlos Paredes’ with Portuguese Fado. At least that’s true for five of the six tracks. For the closer, ‘Jupiter Project’, as if to make a point, we hear Mamer suddenly grab an unused guitar pickup and press it to his throat, his howls twisted through guitar pedals to make a sound that’s half air-raid siren, half late 60s electronic noise experiment. Here, the veil is lifted to reveal the dark, psychedelic monster that lay beneath all along.

Joy MoughanniA Separation From HabitRuptured

Joy Moughanni began his debut album A Separation From Habit in October last year, the same month that, having already waged an aerial bombing campaign and overseen the detonation of explosives hidden in electronic devices, Israel launched a ground invasion his native Lebanon, killing thousands of people – mostly civilians. I’ve written a lot in prior editions of this column about music that helps the listener make sense of societal fracture in its aftermath, but here we find a record created within that fracture, not seeking healing or closure, but dwelling unflinchingly on a present defined by rage, devastation, and grief.

Opener ‘The Voice I’ve Yet To Understand’ is the clearest exploration of the record’s central tenet – how the discomfort of the present finds tragic echoes through time. Here, traditional zajal poetry evokes the communal past, archival radio debates from the 1970s and 80s summons living memory, while Moughanni’s unsettling production places us firmly in the present. On a later interlude we hear the sounds of real bombs dropped during Israel’s first invasion of Lebanon in 1978, while ‘Of Colour And Significance’ elicits the region’s even older colonial scars via the use of a French cassette called Lebanon In Colour. That original tape had featured romanticised melodies played on the qanun (a Middle Eastern string instrument), which here Moughanni stretches and warps into something simmering with rage. It ends, however, in a place that is in a way even more heartbreaking – the 14-minute ambient sprawl ‘To Lose A Friend / A Separation From Habit’ evoking the detachment and suppression necessary to simply keep existing under such conditions.

Vesna PisarovićPoravnaPDV

Sevdah, or Sevdalinka, a traditional form of Bosnian music, makes a good example of the way folksong exists at the intersection of many wider influences. Though its specific history is unclear, the style is known to date back at least as far as the arrival of the Ottomans in the medieval period, while also hinting at earlier Sephardic and Andalusian influences, and has evolved over the centuries through various melodic and instrumental imports from both East and West. After the Bosnian war left many in the country pining for a way to connect to a time before the devastation, the genre began a renaissance that continues today, with a host of musicians from Bosnia and beyond exploring new possibilities from the slow, sprawling, emotionally intense melodies that are the style’s defining traits. Croatian vocalist Vesna Pisarović is one such artist, who on Poravna explores a combination of beautifully sombre Sevdah singing with semi-improvised experimental jazz jams on guitar, drums, double bass and trumpet. It’s quite the about-turn for the singer, best-known in her homeland as a platinum-selling pop star and former Eurovision entrant, but then that’s just one more layer to the fascinating stack of juxtapositions that defines this album – her singing remaining consistent in its assured beauty as the instrumentals ebb and flow in their intensity.

Joshua Arnold And TherineFolk Music Of The British Isles: The Dark And Macabre, Vol. 1Self-Released

The new record by Joshua Arnold and Therine is centred around songs from the British Isles that explore ‘the dark and macabre’. It is, given folk songs’ abundance of darkness, macabreness, violence, madness and general skullduggery, quite the well to draw from. In fact, the North West duo’s biggest hurdle here is setting themselves apart amid the scene’s current slew of hulking doom folk. It’s something they manage deftly by taking a more minimalist approach than their contemporaries, allowing the horror of these songs to be delivered raw and unvarnished and in doing so extracting even more of their essence than most others manage. Therine’s vocals are just that tiny bit off-kilter, giving them that extra cutting edge. Backing comes from Arnold’s guitar, cello, mandolin, dulcimer, harmonium, banjo, glockenspiel, hurdy-gurdy and more, but crucially only a handful of instruments at a time. ‘Death And The Lady’ sets the tale of a maid’s futile attempts to bribe Death with her finery in exchange for a few more days of life to simply guitar and an eerie whistle. ‘Boys Of Bedlam’, so often turned into a high-tempo romp by musicians who take the fantastical imagery of its lunatic narrator (“My staff has murdered giants”), is here presented instead as a sombre meditation on madness – the very real menace that lies behind those fantasies (cutting mince pies from children’s thighs, and so on) allowed to bubble up to the surface. Points where Therine sings entirely unaccompanied (‘Lyke Wake Dirge’, ‘Maid’s Lament’) are more affecting still.

Laura CannellLYRELYRELYREBrawl

In 1939, among the treasures unearthed from the Sutton Hoo ship burial were fragments of a 7th century lyre, thought to have belonged to an Anglo-Saxon king. Now, albeit via a replica, that instrument has found its way into the hands of one of Britain’s foremost explorers of the intersection between early and experimental musics, Laura Cannell. On her 11th album LYRELYRELYRE the instrument’s chimes are interwoven with bass recorders and double reeded crumhorn, as well as with Cannell’s deep research into the lyre’s role in pre-Christian England, to form something totally mesmeric. As Cannell herself has noted, of all the artefacts unearthed in Sutton Hoo and beyond, it’s the lyre’s unique ability to stimulate our aural senses that makes it that much more visceral as a link back to the past. “A physicality and a sound, a language and a feeling that enables us to truly feel connected to our predecessors when we strike the strings,” as she puts it. And indeed, listening to the chasmic reverberations on LYRELYRELYRE, it’s easy to imagine them echoing all the way back to the seventh century and beyond.

Les CaravanesThe CaravanBroadside Hacks

Those seeking an easy introduction to the emergent scene of exciting young British folk musicians could do a lot worse than this compilation of work by members of Les Caravanes, a “travelling folk club” of ever shifting makeup. They take their name from the legendary Soho venue Les Cousins that was central to the 1960s scene and aim, as they put it, “to carry on [its] legacy”, and are composed of members who mostly met through a present-day club, Broadside Hacks, that I genuinely believe will one day be looked back upon with equal reverence. This compilation is acoustic guitar-heavy in its opening third, featuring (among others) a dazzling turn from central figure Sam Grassie on ‘Kishor’s’, and further evidence (following our conversation on the topic for last Autumn’s Radical Traditional) that Daisy Rickman’s voice is almost as well-suited to Nick Drake songs as Drake himself. The album broadens in scope as it progresses, however, encompassing the acrobatic harp-and-vocals brilliance of Polish-born Aga Ujma on ‘Na Polu Sosna Stojala’, unaccompanied turns from Shovel Dance’s Mataio Austin Dean on a rugged ‘John Barleycorn’ and Lileth Chinn on a tender ‘Mountain Streams’, a clàrsach and flute duet from Anna McLuckie and Gail Tasker on ‘Sleeping Tune’, Goblin Band’s Sonny Brazil on accordion for ‘Sherborne Waltz’, a delightful closing collective rendition of Wizz Jones’ ‘When I Leave Berlin’ (particularly poignant given Jones’ death last month) and more. As a document of a scene still in its exciting infancy, this compilation is essential – more so given that all proceeds are being donated to MOAS (Migrant Offshore Aid Station).