In his university days, my older brother liked to play the goat in the clubs and bars of Leicester by telling young ladies he was the son of the rock drummer, Phil Collins. Few were impressed. True enough, our old man did indeed resemble Buster quite closely through his mid-’80s zenith; enough for us to purchase a copy of No Jacket Required for him as a bit of a gag one Christmas. But that archetypal sleeveface moment just never really came off. "I used to like him. Now I think he’s a turd," said Dad.

There can’t be many figures in the world of pop who have inspired quite the same kind of hatred-bordering-on-civil-unrest as Collins, and there can’t be too many who have shifted anything like the 150 million plus units that he’s got through as a solo artist either. But the renaissance of his popularity in recent years – firstly through a US R&B acknowledgement of soul authenticity (which remains utterly bewildering in the UK) and then via a resurgent interest in all things prog – serves to underline what is surely one of the most bizarre career trajectories in pop history.

The glib realm of ‘guilty pleasure’ faux self-consciousness can’t in all honesty lift comfort food pap like Easy Lover out of the 80s musical mire, and nor can Collins’ ensuing Disneyfication, which perhaps aligns him still for many with the earnest vacuum of contemporaries like Sting & Bono. He’s not completely shaken off the misapprehensions of two particular tabloid smears either: the none-more-80s divorce-by-fax episode, and the Tory bluster of a stock "if Labour get in, I’m leaving the country" headline, both probably merely products of waning appeal allied to a jack-the-lad everyman public profile, which, in view of his spiralling wealth, made him the softest of targets. Of course, success and the kudos of cool are two entirely separate things; being portrayed as aloof and right-wing in the 1980s would never buy you any of the latter.

An ever more guarded Collins has repeatedly and strenuously refuted both allegations, but the argument of whether or not he pioneered the ‘gated reverb’ drum sound that became his trademark is a subject he’d no doubt prefer to focus on, and it’s a pointer towards a rarely acknowledged altruistic musicality. Naturally, Tony Visconti and Dennis Davis would have something to say about those drums, but maybe we’ll absolve Phil there on the point of artistic appropriation. Brian Eno too might deny this claim to innovation, if only he would pause in his praising of Collins’ versatility.

According to David Sheppard’s entertainingly labyrinthine biography On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno, the Suffolk poacher is keen to recount a significant episode of mutual appreciation between the two, instigated by Collins. "He said, ‘You know, I’ve always wanted to thank you.’ I said, ‘Really, what’s that for?’ Because I have always wanted to thank him for these bloody parts he played that I’ve reused 800 times." Collins then reveals Eno as the source of (or indeed culprit for, depending on your outlook) his ensuing inspiration. "When I was in Genesis and I became aware of the way you were working, I realised I could do this. If it hadn’t been for you, I would not have had a solo career."

While we’re happy in the main however to forgive true visionaries like Eno and Bowie for their misfiring output – commonly seen as temporary aberrations on the road to an inevitable return to form, ignored lest the petering out of talent besmirch the hallowed majesty of what came before – Collins will never be so fortunate. Publicly defined by stylistic blandness, he’s never been so influential as to drive a scene forward, or spearhead a series of critically lauded releases. Yet diversity and invention are qualities not entirely absent from the Collins canon.

An ardent follower of Motown in his youth, as well as mod favourites The Action, it was with the virtuoso mores of progressive rock (Genesis), and, to a lesser extent, jazz fusion (Brand X) and the blues drama of two John Martyn albums that Collins made his name. Plain dependability doesn’t tell the whole story though: in assisting Eno’s devoutly anti-ability excursions and providing sans-cymbal clatterings for fellow ex-Genesis bighead and latter day vice-Eno Peter Gabriel, Collins found his own voice.

Having lent his treatments to Gabriel’s 1974 Genesis swansong, Eno needed a drummer for his own more ad hoc sessions, and with both outfits recording at the same time and in the same studio, Collins was "sent upstairs as payment" in reciprocation for his efforts. The contributed ‘Enossification’ of tracks on the epic double platter The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway was later only credited as such at Collins’ insistence, and with the returned percussive additions to ‘Mother Whale Eyeless’ from Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), so began a long association between the arch brainstormer and the drummer yet to become the dullest, most conventional rock star of the 1980s.

The finest moments over four Eno albums to feature Collins’ involvement can be found – bookending an appearance on John Cale’s Helen of Troy LP – via the taut neurotic rhythms and peppered scattershot fills of ‘Sky Saw’ from 1975’s ambient watershed Another Green World, and the dry train track motorik snares throughout ‘No One Receiving’, opener of the sublime Before And After Science set from ’77. The latter’s sluggish sister variant would appear as ‘M386’ on Music For Films a year later, whilst both tracks were augmented too by the fretless bass popping of Collins’ Brand X ally Percy Jones.

The offbeat flutter-pulse style deployed for Eno may have been perfected with the exquisite canter of ‘Follow You, Follow Me’, but the 1978 chart breakthrough for Genesis could be seen as an exception to the rule of Collins as wandering boho sticksman, keen to indulge the occasional jazz whimsy or freehand avant garde ad libs to order. The stark difference in character here between Collins and that of Banks and Rutherford is key, and not just in view of their much-documented Charterhouse/grammar school distinction. In an unedifying snapshot from the documentary film of the band’s 2007 comeback tour Come Rain Or Shine, Collins can be seen meekly asking a roadie for his drum seat to be adjusted before scuttling backstage, leaving his alarmingly authoritarian bandmates to browbeat a hapless lighting engineer at interminable length for timing errors.

Yet this apparent validation of the 1980s rock star as CEO caricature (one wonders how Patrick Bateman would have confronted the feckless technician) came to taint the image of Collins almost as much as his detached and occasionally supercilious colleagues; with his head above the parapet as a solo artist, he offered no image whatsoever in response. The contrast here with the session vintage Collins – a Serpico clone in bellbottoms & bucket hat, not so much bearded as carpeted – is an odd one given the blank ordinariness of his later look, an incongruity that Lui Lui Satterfield of the Phenix Horns would define when appraising his appearance as "like some farmer from England" during the making of solo debut Face Value. The implausibly selected image of Collins as a disheveled rock Ewok for his sticker in a 1984 Smash Hits Panini album – issued when the dome-headed, clean-shaven chart imp was already well in the ascendancy as a solo artist – might just pinpoint the moment when the metamorphosis fully took hold.

Given only marginally different career circumstances, Banks & Rutherford would have been equally at home with the cultivated precision of the dental practice they occasionally seemed destined to oversee, and despite possessing an abundance of technique and technology, they only coaxed all the wrong sounds from the hardware at their disposal in this life. Collins however would enjoy the fruits of some considerably more Eno-esque approaches to recording during further nomadic pursuits, this time with the man who’d already been basking in his liberation from the Genesis consultancy firm for five years.

After adding drums and backing vocals to the somniferous intensity of John Martyn’s impassioned break-up LP Grace & Danger, Collins was employed by Peter Gabriel for work on his third eponymous album, with the strict remit of "no metal". At Gabriel’s newly converted farmhouse in Bath cymbals were duly discarded, and on the twitchy opener ‘Intruder’ a rudimentary thump was gilded by a now legendary piece of engineering. While Collins played, Hugh Padgham (the engineer who would graduate to production duties on albums for both Collins and Genesis throughout the 1980s) ruminated upon the sound feeding into the SSL console’s listen mic, and in an inspired moment magnified the heavily compressed effect by adding a noise gate. The track’s eerie, claustrophobic hum had gained its spine, and the ‘Phil Collins drum sound’ was born. Heavily influential for many artists as one of the most frequently imitated sounds of the era, Public Image Ltd would gain particular inspiration from it for their Flowers Of Romance album. In turn, Collins was so fond of PiL’s art rock racket that he plundered assistant engineer Nick Launay – latterly known for producing Nick Cave and The Yeah Yeah Yeahs amongst others – for his own debut solo project, which took shape during an acutely emotional creative spell in 1980.

In an inspired flurry at the turn of the decade, and seeking cathartic release from the fallout of his first marriage, Collins would set about both the realisation of his own material for the first time, begin work on another Genesis LP, and gravitate once more towards the similarly fraught John Martyn, taking his bow as producer on the singer-songwriter’s Glorious Fool album. He’d also use Face Value‘s lead single to demonstrate how the unconventional studio predilections of Brian Eno and Peter Gabriel had rubbed off on him to launch a rock oddity classic.

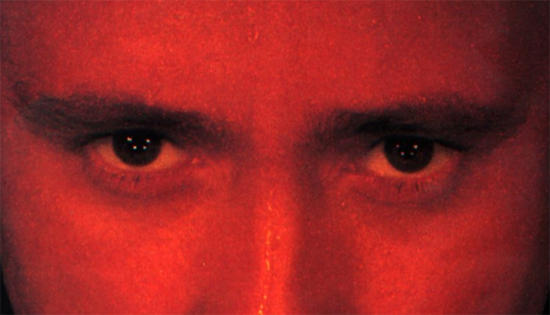

What ‘In The Air Tonight’ has become in the public consciousness might reflect its brooding opening two-thirds and then the familiar Phil-falling-down-the-stairs-with-his-kit explosion of full-blown melodrama, or indeed the lyrical subject matter, seemingly bilious in its pointed attack on a betraying partner though apparently improvised at the mic during early demos and retained. Clouded over by the remaining career’s worth of sonic stasis however is the single’s place in 1981 at the vanguard of experimental pop, every bit as ambitious as ‘Games Without Frontiers’ from the previous year. Collins teases at a Prophet synth and vacuums the life out of the second verse with a Vocoder blare, yet the track’s key intonation is derived somewhat paradoxically from a drum machine. Whilst Gabriel favoured a PAiA set for the electro-funk coda to Frontiers, Collins effected a coagulated, compressed undulation for ‘In The Air Tonight’ courtesy of the Roland CR-78. The machine’s silvery comatose plod forms a pleasingly awkward companion to the emergent dominance of the ‘Collins sound’, whose contrary whackings, appearing at 3:41, heralded the decidedly unsubtle timbre to come. John Giblin’s bass and Shankar’s strings zig-zag their theatrical dominance into the outro, and what should have constituted Collins’ announcement as a singular pop force – and not merely the foremost exponent of AOR mediocrity – fades out.

To say that Collins’ ingenuity as a solo artist began and ended inside three minutes and within one song may seem a little unfair, though in reality that’s almost how it panned out. Face Value includes other, albeit muted highlights, but it’s no Revolver in terms of front to back quality and cutting edge – and, sure enough, the cover of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ duly misfires. Second single I Missed Again has its carefree jilted skip enhanced by Earth Wind & Fire’s Phenix Horns and a punchdrunk Ronnie Scott tenor solo, though it was arguably a poor relation to ’81’s white soul highpoint – and another exemplar of the CR-78’s merits – ‘I Can’t Go For That (No Can Do)’ by Hall & Oates, later fellow Padgham-pushers themselves. Similarly, ‘If Leaving Me Is Easy’ possesses a lush Arif Mardin arrangement reminiscent of the opulent synthetics of ‘I’m Not In Love’, but suffers now as a forerunner of the heavy syrupy balladeering that would characterise later solo efforts. But it was those even bigger releases to come that swiftly cemented the perception at large of Collins, firstly as an artist, and subsequently in terms of the way his character was portrayed. And to a great extent, it’s almost impossible to fight his corner on the basis of the output.

As Eno escaped with a more or less spotless reputation after traversing the light year’s distance in production values between Talking Heads and U2, Collins likewise headed unblinking into the mainstream, and kissed goodbye to any trace of creative eminence that his nascent solo career had thus far afforded him. Gabriel, after a stuttering start, eventually soared into the decade’s back end as the canny Fairlight & fretless slick-yet-intellectual archetype, while any such element of risk for his Genesis successor was apparently forever deluged in an all-out commercialist sonic dysentery. The hits just piled up, only to become increasingly forgettable and trivial, whilst the Collins of the mid-to-late 1980s was a ubiquitous, vapid yet outrageously profitable disappointment.

And never had such an unrelenting arbiter of the casual provoked such ire. An ever more be-sweatered, stubbled but successful figure mugged his way through countless promotional and globally broadcast appearances to simultaneous emergent fury, whilst the video age would burn Collins just as much as it would benefit him. ‘In The Air Tonight’ may have been aired on MTV’s opening day, but the ‘regular guy’ shtick would only look absurd in the context of the ‘Take Me Home’ video’s perceived capitalist ostentation. Meanwhile any vestige of appeal to the youth market (something he admittedly never courted) would be similarly extinguished via the kind of cornball nonsense displayed in the extended clip for ‘Don’t Lose My Number’.

By the time of 1989’s …But Seriously album, it had become utterly impossible to reconcile the worldwide lowest common denominator megastardom Collins with the hepcat beat merchant that graced a key cache of vital pioneering UK rock recordings over the previous decade. Indeed, for many the contemporary incarnation’s immovable weight rendered the discovery of his credit on those early albums as something of a queasy letdown: it couldn’t be that Phil Collins, could it?

As part of a pool of late 70s post-prog talent however, Collins is unquestionably the square peg, and the 1979 Exposure album, helmed by Robert Fripp and featuring Eno, Gabriel and Collins (and most curiously Daryl Hall too) assembled this axis of innovation. Collins bashes out his part on the raucous ‘Disengage’, before changing tack for the ride-led astral beauty of ‘North Star’, where Hall’s gospel throat dovetails neatly with Eno’s sirocco synth and the open-chord anchoring of Fripp. But the album couldn’t paint Collins in the same artisan tones as his pals, and in his sleevenotes to the 2006 re-issue, Fripp unwittingly elucidates as to why, when out on his own, Collins flailed in terms of innovation yet found the mining of a particularly corporate-friendly songwriting skidmark irresistibly attractive. Fripp’s lament in negotiating the tensions of art versus commerce with RCA over the involvement of Daryl Hall could equally be read as a most pertinent summary of where Collins’ instinct took him:

"The creative impulse involves hazard: there are no guarantees. Business demands guarantees and rewards certainties, even though certainty is often unfulfilling and unsatisfying. An artist who follows the muse is perceived by business as dangerous."

Perhaps ultimately it was the soft option that sealed Collins’ reputation, placing him understandably at odds with any notion of a relationship with the leftfield. The disgrace of a career bogged entirely in the determined dross of No Jacket Required however is simply not justified, regardless of how Collins gained either his fortune, or his public image.

Having been introduced by Nick Launay, Collins and John Lydon got on "like a house on fire" when recording respectively at Virgin’s Townhouse studios in West London back in the early 80s; clearly not everyone was quite so averse. Maybe looking like your Dad need not be such a hindrance after all.

Gary Mills is an arch ruminator, known to a disturbed handful for former input as conceptual mekon and sleeve artist on a number of releases from the esoteric Mordant Music stable. Latterly employed by virtually no-one as careworn scribe and admin clerk. Also records epitaxial ballads and runs himself into the ground. Slim of waist.