Anyone who pays attention to the news today, or has done so over the last decade, can’t have failed to miss numerous stories concerning murder, terrorist plots, and child sexual abuse being linked to neo-Nazis.

The origins of this new wave of neo-Nazi terrorism can be traced to the online forum Iron March, a hate site and platform which united groups such as the British fascist organisation National Action who were involved in a plot to kill MP Rosie Cooper, and Australia’s Antipodean Resistance. New groups formed on the forum, too, most notably in 2015 the US-based international terrorist group Atomwaffen Division, whose members and associates have committed five murders in that country alone. They disbanded in 2020 but influenced similar groups, such as their British affiliate Sonnenkrieg Division (which included National Action members) and the Feuerkrieg Division. As authorities cracked down on these groups, propagandists migrated to the social media platform Telegram to spread their ideas, forming a series of channels dubbed Terrorgram.

These in turn have cross-pollinated with ideas generated by advocates of other extremist philosophies, creating strange new hybrids. These include the Order of Nine Angles, a neo-Nazi Satanist grouping which encourages murder, which was covered by this site in 2018 after an attempt to infiltrate the UK DIY underground, which has crossed over with online child abuse cult 764. There have been over a dozen documented murders arising from these neo-Nazi networks.

And this terrifying global network can have its intellectual core traced back to one single book: Jame Mason’s Siege. And it, in turn, only exists because of the efforts of a handful of people in a corner of the 1980s counterculture who worked together to make its publication a reality.

Siege’s ideas may have been generated in the early 80s but they are central to the network’s philosophy today; the Atomwaffen Division required all members to read the book, one calling it the group’s “bible”. Siege is an abridged anthology of newsletters of the same name that Mason published between 1980 and 1986. In them, he worked out a new neo-Nazi philosophy based on his experiences after joining the American Nazi Party in 1966. Mason concluded that any kind of traditional political work, such as holding marches or forming organizations, was useless; society wasn’t going to let a neo-Nazi party take power. Instead, he advocated random acts of terrorism: massacres, assassinations, even serial killings. He counseled adherents to commit atrocities in a highly visible manner and with what he considered ‘panache’. The hope was that they would create enough panic and chaos that “The System”, as he called it, would destabilize and give neo-Nazis a chance to seize power. And if this wasn’t extreme enough, he praised Charles Manson, who he was in direct touch with, as the new neo-Nazi guru.

But the problem we face today is that not all neo-Nazis are like James Mason. They don’t all wear uniforms; they don’t all write political tracts. Today’s subcultural scenes – from techno to neofolk, black metal to noise, industrial to oi, folk to hardcore – can harbour fascists and fascist infiltrators. They’re hard to spot precisely because of the lack of uniform and political tracts, and their politics are frequently cloaked in ambiguity and denial.

The links between today’s neo-Nazi terrorist networks and the kinds of subcultural scenes that have either been prone to infiltration or have been slow to call out the development of neo-fascist strains in their own ranks, can now be seen clearly in a clique of four figures from the counterculture of the 1980s and 1990s: Boyd Rice, Adam Parfrey, Nikolas Schreck, and Michael Moynihan. Despite some criticism for using the imagery of, being connected to, or helping to promote neo-Nazism, they have enjoyed long careers simply by dismissing, downplaying, or simply denying these accusations.

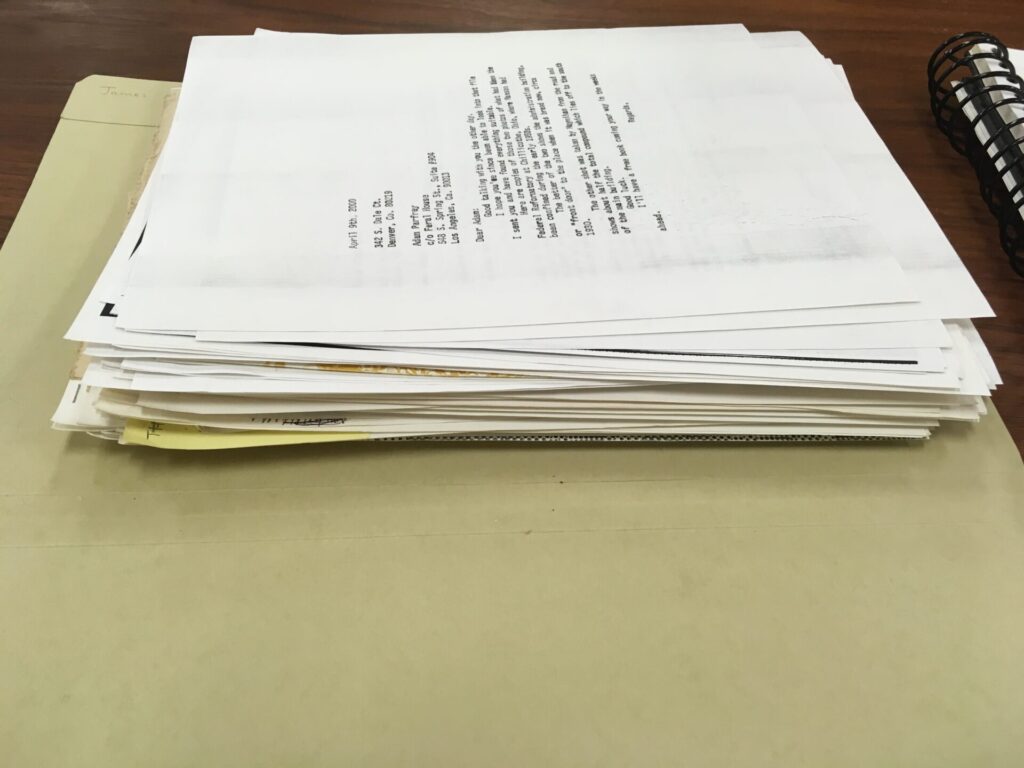

However, a collection of James Mason’s letters, located in an archive at the University of Kansas, in Lawrence, KS, have shone a bright and unforgiving light on these matters. So much so that I spent five years studying them in order to excavate this history for my book Neo-Nazi Terrorism And Countercultural Fascism: The Origins And Afterlife Of James Mason’s Siege. What follows is a story of countercultural complicity in inspiring a movement fixated on murder.

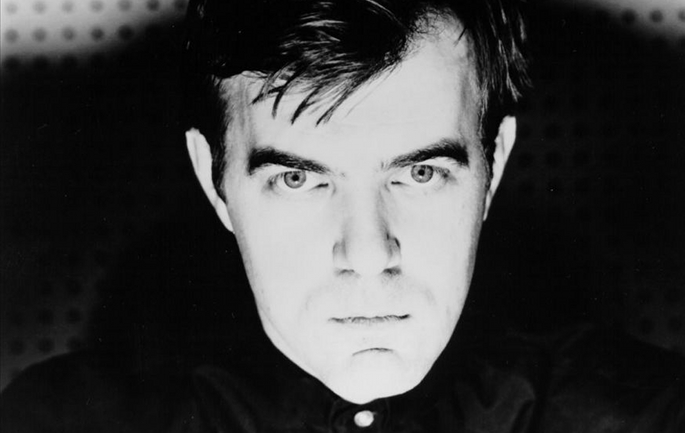

In the late 1970s Boyd Rice was a Californian experimental musician, artist and photographer who showed great potential, making avant garde albums of loop music using early samplers, tape recorders and, taking up the gauntlet thrown down by John Cage, multi-speed turntables. But by 1979 he’d sensed that the wind was now blowing in a different direction. One of the five tracks on his debut 7” as NON called ‘Knife Ladder’ places him as an early adopter, rather than pioneer, in the industrial sound minted by Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire some years earlier in the UK. The 7” is a collector’s item as all copies have an extra ‘multi-axial’ hole drilled near the centre, and some copies have up to three extra holes for the spindle. But his philosophical and pranksterish provocations regarding sound were soon to head in a darker and more serious direction, as he became fascinated with the history and aesthetics of fascism.

Rice has gone on record many times saying he is not a neo-Nazi, even though for a decade he called himself a “fascist.” But there is plenty of documentation of his collaboration with neo-Nazis, and several examples of Rice presenting himself as one. In 1988 Rice and the musician Nikolas Schreck formed the Abraxas Foundation, a self-proclaimed “occult-fascist think tank”. Schreck was a writer and fronted the camp goth band Radio Werewolf, founded in 1984. As the 80s progressed Radio Werewolf also seemed to realise that there was more mileage to be gained from transgressive button pushing rather than just gigging their Rocky Horror organ-driven garage punk around California. Schlock and horror lyrical concerns such as serial killers and vampirism were the order of the day, but then so were an ever growing number of references to the Third Reich in comic songs called ‘Strength Through Joy’ and ‘Triumph Of The Will’.

The third member of the Abraxas Foundation was the underground publisher Adam Parfrey, who was in the process of co-founding Amok Press whose first title was an English translation of Michael, a novel by Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels. He co-edited a magazine and founded two presses which all became important publishing ventures, and which he used to publish the other members of the Abraxas Foundation, as well as Mason.

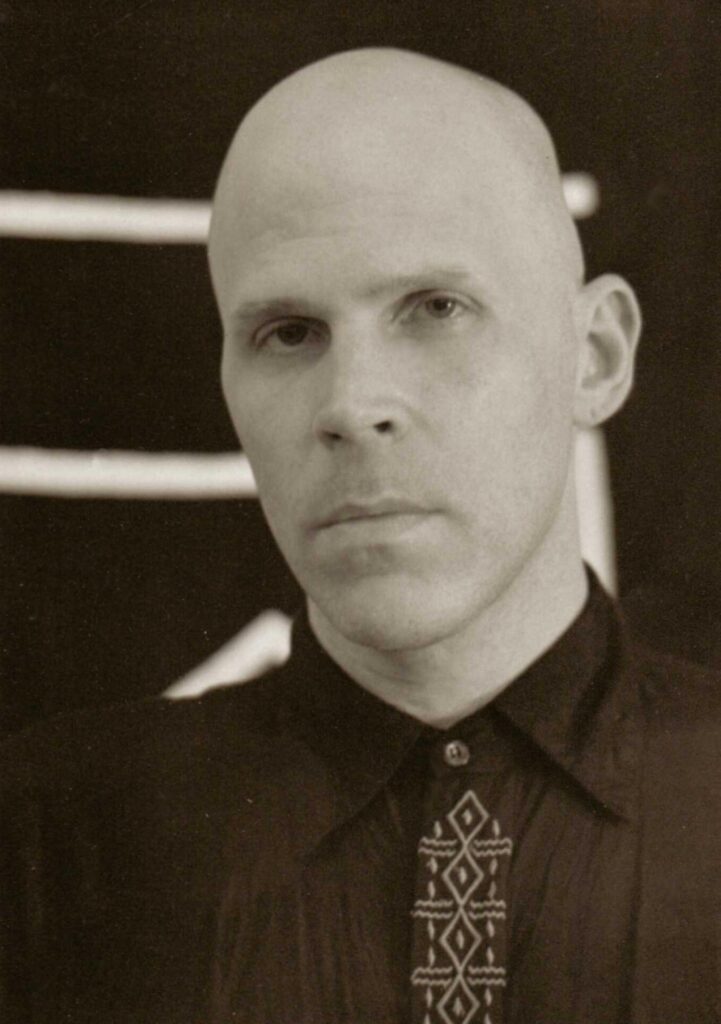

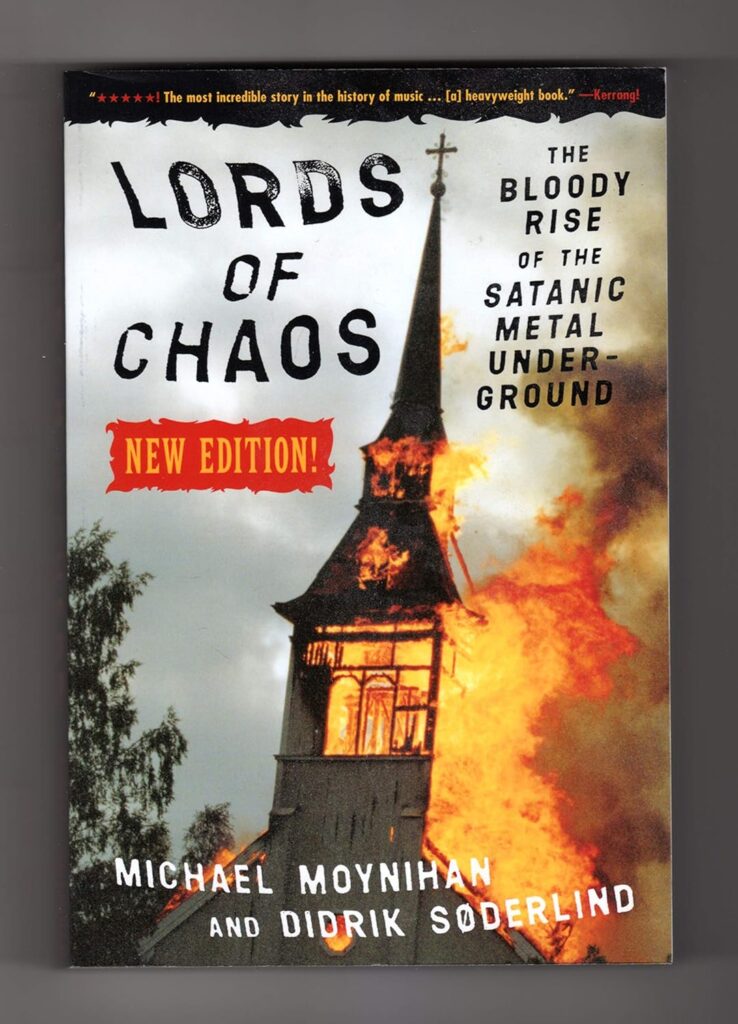

Another key member was Michael J. Moynihan. Slightly younger than the others, in the 1980s he played in Sleep Chamber, issued cassettes by his industrial project Coup De Grace and, in 1989, joined the Abraxas Foundation. In the 1990s he and Boyd Rice became flatmates in Denver, he founded the neofolk band Blood Axis, co-authored Lords Of Chaos, one of the foundational books to chart the rise of Norwegian black metal, and, in one bizarre incident, was questioned by the Secret Service over a plot to assassinate George W. Bush. No charges were filed.

Together, the Abraxas Foundation discovered, promoted, and popularized the philosophy and tactics of James Mason, ultimately culminating in his book Siege.

All have vehemently denied they are neo-Nazis, and in this they have the full support of many musicians, artists and journalists, but in fact, the four of them were connected to, or in contact with, three prominent figures who were part of the most violent wing of the 1980s neo-Nazi scene: Mason, Tom Metzger of the White Aryan Resistance; and Nazi skinhead gang leader, Bob Heick of the American Front.

Shards of evidence about the four and their involvement with Mason have long been available in the public realm but unfortunately much of what has been written has been marred by garbled information and speculation. The main exception is Kevin Coogan’s 1999 Hit List magazine essay, ‘How Black Is Black Metal’. Coogan was a talented researcher and the author of the biography Dreamer Of The Day: Francis Parker Yockey And The Postwar Fascist International. In the Hit List article, Coogan was able to get hold of obscure fanzines and other rare materials, and put together Moynihan’s story, in particular, based on verified sources.

However, the numerous letters between the four and Mason conclusively show that their involvement was much deeper than anyone had previously guessed at, and the new evidence more damning than that previously uncovered even by the most careful of researchers.

Mason had sold over 60 boxes of his correspondence to the University Of Kansas archive. Not just a neo-Nazi activist and propagandist but a neo-Nazi insider and neo-Nazi networker as well, he had one eye on posterity and kept not just the letters he received during the period that spanned the 1960s through to the early 2000s, but also carbon copies of his replies. Although the collection’s finding aid was readily available online, these documents had rarely been used by researchers of the Far Right – much less by those looking into countercultural politics.

I stumbled upon the archive in 2018. I was laying low after the August 2017 counter-demonstration in Charlottesville against Unite The Right, the largest fascist-led rally in decades in the US. It ended with a neo-Nazi car attack that killed one person and injured about 30 others. I wrote about being in the crowd during the attack, leading me to being swamped with threats afterward. Siege had skyrocketed in popularity as it seemed to have predicted the outcome by arguing there was no point in holding such public events. (The rally itself was never held as police dispersed participants right when it was supposed to start.) I was writing an article about Mason, but the existing published details about him were inconsistent; when I found out about the archive, I went there to clear things up. The collection of letters was an incredible thing to come across, and it took me five years to write the book they went on to inspire.

The accusations that Boyd Rice is a neo-Nazi stretch back for decades now, and while he’s always batted them away, his involvement in the neo-Nazi milieu was both long running and serious, as his handwritten letters to Mason show.

This part of the story starts on 24 April 1986 when Rice sent the first of at least fifteen letters to Mason. Most of them are neatly hand-written in pen on yellow lined paper. Rice, who since has published several books, uses a smooth conversation style in them. He shared a fascination, common with some of his peers on the industrial scene, with Hitler and Manson. In his first letter, Rice was unequivocal: “I am completely of the Manson-Hitler thought & do whatever I can to further it.”

Upon receiving copies of Mason’s newsletter, Rice wrote back: “Love the SIEGE!” Within a month he had suggested turning the newsletters into a book – undoubtedly the first person outside of neo-Nazi circles to do so. Rice said a book could take Mason’s ideas and put them “out in the world to take root, grow & become something of a life of its own.”

For a few weeks in 1986, Rice visited Charles Manson in prison; he later gushed to Mason that visiting the cult leader was like “having the chance to spend four or five hours with Hitler every week… imagine how much you could learn”. Towards the end of that year, Rice went on Tom Metzger’s syndicated cable access TV show, Race And Reason. Espousing revolutionary racial separatism, Metzger was one of the most notorious U.S. neo-Nazi leaders of the 1980s. He used crude racist and antisemitic images in his newspaper as he successfully courted the Nazi skinhead movement. As part of his show he interviewed a variety of white supremacists and Holocaust deniers. At its height it was on the air in 62 cities, spread over more than 20 states. During one broadcast Rice wholeheartedly agreed with Metzger’s assertions that industrial music was “a new propaganda art form for white Aryans.” Asked about “racial separatism and tribalism,” Rice said “it seems like the only intelligent way to go.”

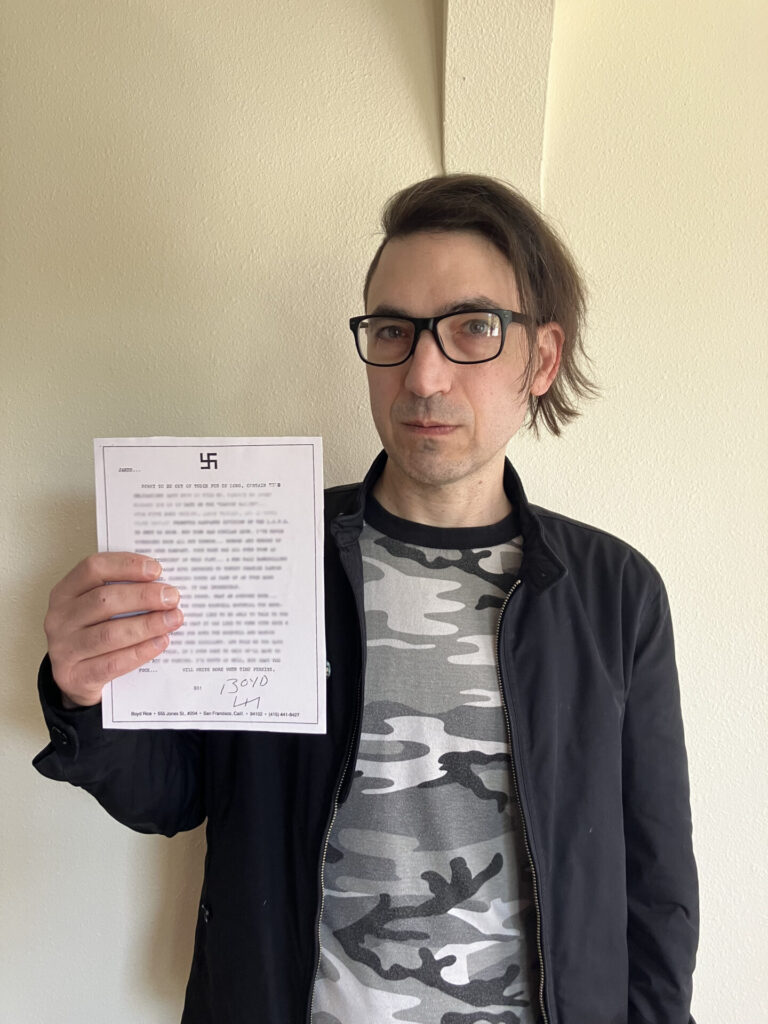

Afterward, Rice was very positive about Metzger, writing: “I liked him a hell of a lot. Like his attitude and his outlook. He’s really doing it!” During the same period Rice released a new album, Blood & Flame, which includes a quote from Nazi Party antisemitic propagandist Alfred Rosenberg. But this was just the start, and many Nazi and far right references would follow in his albums, art, and clothing. As his correspondence with Mason continued, Rice revealed that he was reading American Nazi Party leader George Lincoln Rockwell’s “awesome” book White Power. The letter he sent to Mason was decorated with a swastika at the top of the page.

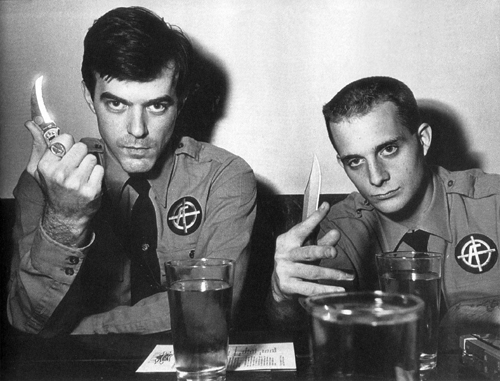

At this time, Rice also became close to Bob Heick, or, to use his own words, he was “good friends” with him. Heick was the leader of the Nazi skinhead group the American Front, based in San Francisco but who were becoming the first national Nazi skinhead group in the United States. At the time, they conducted their relationship openly. They appeared together in TV feature on racism broadcast for USA Today; Rice drew a swastika on a wall as Heick was being interviewed. But it was a 1989 photograph featured in Sassy – a popular teen girls magazine – that would follow Rice around for years. The picture was part of an otherwise unexceptional feature on Nazi skinheads, whose movement was receiving a huge amount of coverage in magazines and TV shows at the time. In the photo, they were both wearing American Front uniforms and holding knives.

In 1986, Rice also told Mason he should meet a friend of his from “Jew York”, and introduced him to Adam Parfrey. Parfrey was just three years away from launching Feral House, a darling imprint of those obsessed with gnarly and transgressive literature as well as conspiracy theories. They would go on to sell hundreds of thousands of books, some of which have been made into movies, such as Ed Wood and Lords Of Chaos. In short: Feral House had an audience. When he died, no less a publication than the New York Times ran an obituary for him.

Parfrey also became fascinated by Mason, writing him over thirty letters. When he first did so, Parfrey was co-editing the art magazine EXIT with George Petros. (Petros would go on to co-edit the 1990s music magazine Seconds, and become a contributing editor at the art magazine Juxtapoz and senior editor at the goth magazine Propaganda.) EXIT’s use of Nazi imagery was such that it convinced Mason that Parfrey was one of his own. In his early letters, Parfrey said the publication was “aimed at cynical and lazy but ‘hip’ young people. We feel it is a propaganda tool to legitimize a certain type of thought among race-mixing and otherwise polluted people”. While openly admitting that his mother was Jewish, nonetheless Parfrey told Mason that, “I am sympathetic to all your stated ideals in Siege, and particularly your edict to Race Traitors.”

Parfrey soon became the first person outside of neo-Nazi circles to publish Mason both in a magazine and a book. Mason’s work appeared in the third issue of EXIT in 1987. That same year were the first releases by a press Parfrey had just-founded, Amok Press (not to be confused with Amok Books). One was a now-notorious anthology Parfrey edited called Apocalypse Culture. A compendium of extreme material – including one of Mason’s flyers, material created by other white supremacists, and an interview with a necrophiliac – it became an underground classic. After a fallout with his business partner, Parfrey founded Feral House press, and the anthology migrated with him. In 2010, it had reportedly sold 100,000 copies and remains in print – meaning that Feral House is still making money off James Mason.

In 1987, Parfrey went beyond publishing neo-Nazis, and instead was published by them. After meeting Metzger, the white supremacist printed a collage by Parfrey called ‘The Revelation Of The Sacred Door’ in his newspaper White Aryan Resistance. Even at the time Parfrey knew that this wasn’t something that would play well in public, and the image wasn’t signed. In January 1988, Mason pitched a Rockwell biography to Parfrey, who was “very interested.” But the pitch came in just as Amok Press was collapsing, and Parfrey became concerned he was getting a reputation as a Nazi publisher. In October 1988, as he confirmed in a letter to Mason, the book was still on, but cautioned: “I’m counting on heavy censorship, condemnation and subtle boycotts by ZOG [Zionist Occupied Government] when it appears. I’m trying to get together a book written by n****r and spic gang members on youth gangs for release at about the same time. To me, letting these cocaine-addled n****r murderers prattle on about their miserable lives will be rope enough for them to hang themselves. But then I can always point to the book when the ADL gets on my case about racism, neo-Nazism, etc.”

Parfrey continued to use this kind of language in his letters to Mason, for example calling Michael Jackson a “little monkey.” He seemed to have a particular hatred for developmentally disabled people, calling his band The Tards. Latinos were another target. Referring to the Mexican immigrants who lived in his neighborhood, Parfrey said, “a country that is overcome by immigrants of racial difference would have been called an ‘invasion’”.

Despite consistent claims that Parfrey’s relationships with white supremacists existed solely so he could convince them to let him publish their work, Parfrey did not print Mason’s book, or anything else by him, after 1988. Yet he continued to proactively help Mason out by buying his archival materials, giving him marketing advice, and offering to pay for ads. Mason even claimed that Parfrey had offered to help with the second edition of Siege in 2003.

Nikolas Schreck was the first person to put Mason in a film. Schreck’s band Radio Werewolf, appeared on Metzger’s TV show in 1987, although it is clear that the band are not fascist, rather are treating the exercise as a joke. If anything the host Metzger appears to be confused by the encounter. In 1988, Schreck edited the Manson File anthology which included several pages about James Mason and the musician would also feature a talking head interview with the neo-Nazi in his 1989 documentary Charles Manson Superstar. It was published by Parfrey, and it also went on to become an underground classic. Schreck made a return appearance on Metzger’s show in 1988 and this time he angrily denounced “race mixing, genetic suicide, the destruction of the gene pool”. It no longer sounded like he was joking.

During the same year Schreck became involved with Zeena LaVey, the daughter of Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey. On 8 August 1988 Schreck, Zeena, Parfrey, and Rice performed one of the more public parts of this story: the 8/8/88 performance, a clear neo-Nazi dog whistle. (“88” is the alpha-numeric for “Heil Hitler.”) It came as the Nazi skinhead movement exploded across the United States during the so-called “Summer of Hate”. In fact, only three months after the event, a Nazi skinhead gang affiliated with Metzger murdered Ethiopian immigrant Mulugeta Seraw.

The 8/8/88 event was held on the anniversary of both the Manson Family murders and a “destruction ritual” by Anton LaVey, giving it a Satanist slant, too. (Schreck, Rice, and Moynihan all joined the Church of Satan, while Parfrey became LaVey’s publisher.)

A group photo from the event shows people sieg-heiling, including Rice, Schreck, Zeena, and the white supremacist Heick. Behind the camera was Nick Bougas, a cartoonist for Metzger’s paper whose antisemitic caricature “Happy Merchant” has become a famous if repugnant meme. The participants played it off as a wind-up. However, some were maybe joking and others certainly weren’t. The photo itself is now hard to find so arguably they weren’t proud of it. Parfrey clearly made a point to step out of the frame during this particular take (one taken during the same session without raised arms includes him). Parts of 8/8/88 were included in the two-hour Geraldo Rivera TV special ‘Devil Worship: Exposing Satan’s Underground’, which was seen by almost 20 million people. The event was a masterclass in “wink-wink fascism”. In public they acted like neo-Nazis, but then assured people it was a joke – all the while actually being in direct contact with neo-Nazis. After the event, Rice wrote to tell Mason: “We’ll use whatever label necessary to put out our thought.”

The role of Michael Moynihan in promoting Mason has been the most publicly conducted of the four, as he both edited and published Siege. In early 1989 Moynihan started writing the first of about one hundred letters he would send to Mason. Moynihan quickly agreed to edit Mason’s newsletters into a book, and sent him a series of letters festooned with swastikas. In 1991, Moynihan and Rice appeared as guests on Christian preacher Bob Larson’s radio show, which featured a call-in from Mason. Moynihan was introduced as a representative of Mason’s Universal Order, the name of both a group that only existed on paper and a concept that Mason described as a type of National Socialism. (Moynihan would later represent Universal Order at a 1994 art show.) In 1992 Mason also moved to Colorado, and letters from both Moynihan and Rice decreased but only in favour of in-person visits and phone calls.

In April 1993 Moynihan finally self-published Siege. In its introduction, he said that the book could act both as a guide for the curious, but “more importantly, this book is meant to serve as a practical tool. A majority of readers will hopefully… be already predisposed towards these ideas”.

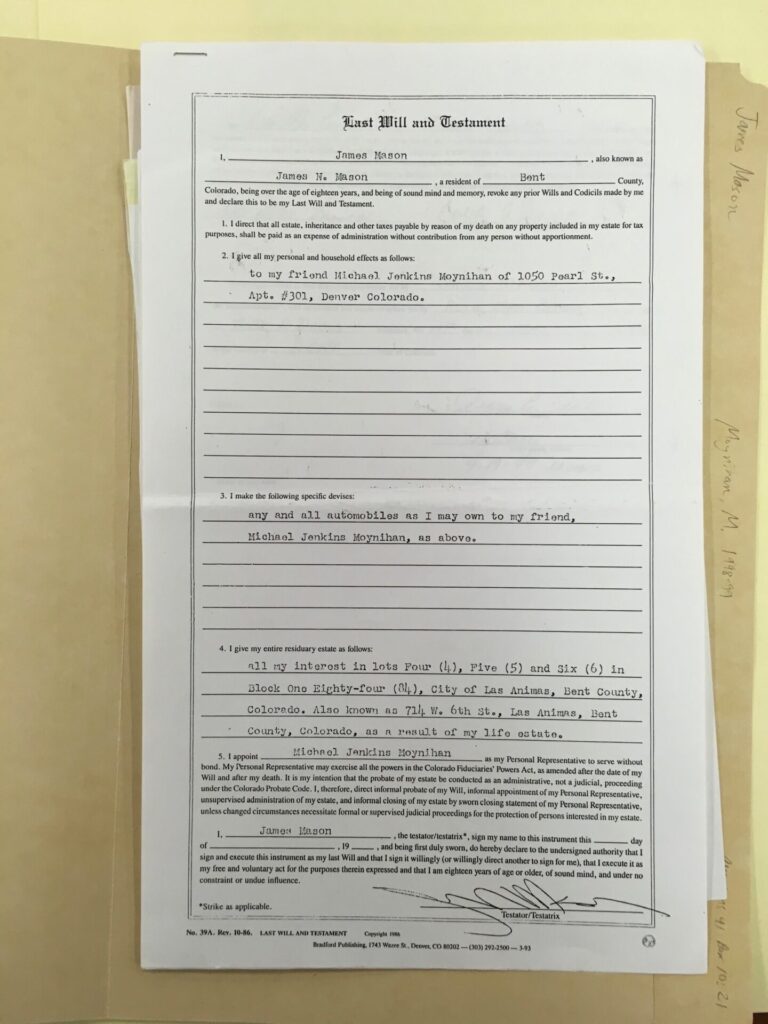

In addition to getting an impressive amount of coverage of Siege in alternative weekly newspapers and music zines, Mason went on Larson’s show a second time in 1993, with Rice accompanying him in the studio. Mason was so thankful to Moynihan that he left everything to him in his will.

In 1992 and 1993, Moynihan was becoming more established in the mainstream world of heavy metal journalism and by 1994, he had already started work on Lords Of Chaos. Traveling to Norway, he interviewed black metal musician and evangelical racist Varg Vikernes of Burzum, who was imprisoned for killing the guitarist of Mayhem. Moynihan gave Vikernes a copy of Siege, and the Norwegian in turn wrote to Mason informing him that his ideas were “very familiar. If I had read Siege, let us say one or two years earlier than I did, it would have been a great help to me – really.”

Lords Of Chaos, also published by Feral House, was the introduction to the notorious Norwegian black metal scene for many people; and it was also a hit. By 2000 it had sold 20,000 copies, and eventually spawned a 2018 film. In order to make sure his success wasn’t ruined by claims he was a neo-Nazi, Moynihan ran a disinformation campaign, convincing many writers to print his sanitised version of events. His history with Mason was not forgotten however, and in response to protests and articles about him, Moynihan gave a series of interviews where he lied about and obfuscated his background. His crowning achievement was a cover story in a Portland, Oregon alternative weekly, where Moynihan’s interviewer claimed his critics were engaged in a “jihad” against him. But the accusations levelled by his critics were for the most part correct, as supported by his correspondence with Mason.

The crucial help these four provided to Mason did not blow back on them, or at least not too much. Parfrey moved on to less offensive – although still extreme – material, although he privately kept up his connections to Mason until 2008. He also stayed in touch with some members of the neo-Nazi movement, appearing on a couple of white supremacist radio shows just before his death in 2018. Schreck fell out with the other members of the Abraxas Foundation in 1989, and in 1990 both he and Zeena broke with her father, Anton LaVey and the Church of Satan. They moved to Europe and continued what might be characterised as a ‘spiritual journey’, joining and leaving the Temple of Set, then forming the “Sethian Liberation Movement”, before becoming Tibetan Buddhists. Today Schreck says he was never a neo-Nazi although he did believe everything he said at the time, and he identifies as “Eurocentric”, although not a separatist, and is against “miscegenation”, but, he adds, he does not want to force his view on others. Rice stayed in touch with Metzger until at least 1996 and with Mason until 2003. Surfing the continual controversy about him more or less successfully, Rice did later complain it cost him some opportunities. Still, despite protests he was able to open for Cold Cave’s 2013 tour – although other events, such as a 2018 art show in New York City, were cancelled, and he continues to command a modest if dedicated fan club. Moynihan became an open Heathen ethno-separatist and kept publishing and recording, even completing a PhD in Germanic studies at University of Massachusetts Amherst. Apparently promoting neo-Nazi terrorism was not the career killer one might assume.

James Mason’s influence on the current wave of neo-Nazi terrorists cannot be underestimated, and nor can their violence as their crimes continue to increase at a steady clip. The fact that Mason, his book, and the groups inspired by him have been proscribed in numerous countries attests to this. But the role of the four members of the Abraxas Foundation in the creation and dissemination of Mason’s masterwork, as well as their involvement with neo-Nazism more generally, has not received nearly as much attention. Without them, Mason’s newsletters would likely exist in the same obscurity that they were published in. While the Nazi skinhead movement is well-documented, a greater spotlight needs to be shown on the role of this corner of the 1980s and 1990s counterculture in creating the neo-Nazi movement as we know it today.

Neo-Nazi Terrorism and Countercultural Fascism is out now via Routledge