A glorious affirmation of working-class creativity, The Minutemen’s Double Nickels on the Dime is a left-modernist epic that draws inspiration from James Joyce’s Ulysses, post punk, free jazz, country and folk. Tearing through 47 tracks in just under 80 minutes, the trio of guitarist D. Boon, bassist Mike Watt and drummer George Hurley present a vision of punk that is stylistically plural, politically committed, humane, earthy and absurd, all underpinned by an econo philosophy that remains an inspiration to DIY artists forty years later. Like Ulysses, Double Nickels is a cosmopolitan work of art that draws great strength from the community its authors came from. But while Joyce had to leave Dublin in order to write his masterpiece, The Minutemen made a point of staying in San Pedro, a working-class port at the southern edge of Los Angeles.

It would be a stretch to argue that the whole album is modelled on Ulysses (itself modelled on Homer’s Odyssey), but several tracks take inspiration from Joyce’s novel, particularly his use of different writing styles. There are broader parallels, however. As Watt told Michael T. Fournier, author of the 33 1/3 volume on the album, “[Joyce] was trying to write about everything. And in a way, the Minutemen were trying to do the same… the whole world, the history, the future, what can be, could be, would be, what might have been. So, we’re overreaching, and this is the thing we get out of it.”

Just as Joyce radically expanded the possibilities of the novel, the Minutemen made good on punk’s liberatory promise, embracing “freedom and going crazy and being personal with your art.” As Watt told Michael Azerrad in Our Band Could Be Your Life: “It was natural that we would want to make music that was a little different because that, for us, made a punk band.” Farting in the face of punk orthodoxy, Minutemen covered Van Halen and Steely Dan, and borrowed their double LP’s structure from Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma. Yet for all the experimentalism – the guitar solos, the freeform guitar and percussion tracks, the spoken word pieces – Double Nickels retains the concision and energy of the Minutemen’s earlier releases.

The principle of jamming econo applies not only to their music, but their DIY mode of operations. In addition to mucking in with the day-to-day running of Greg Ginn’s SST label, the band were their own roadies and learned how to fix their van. Mark Wardlaw notes that while writer and SST employee Joe Carducci frames the band’s self-sufficient approach in right-wing libertarian terms, the band’s own ethos was explicitly communitarian. As Azerrad puts it, ideas about redistribution of artistic power were a powerful analogy for redistribution of political power. For Watt, “the way we jammed econo was the same way we talked about issues… We didn’t have the political rap and the band rap. They were the rap.”

Like Ulysses, Double Nickels stands with the working man, the exploited, the misfits and the oppressed, while avoiding the macho or sentimental cliches that can plague social realism. Anti-imperialist and anti-nationalist politics are threaded throughout both texts. Joyce takes on the British Empire, the Minutemen America’s hawkish foreign policy. Perhaps most importantly, they assert that art, beauty and the avant-garde should be accessible to all, exploding elitist notions of high and low culture. As Watt told Azerrad, “Boon believed that working men should have culture in their life – music and art – and not have it make you adopt a rock & roll lifestyle lie… See, that’s punk. Having a set-up paradigm and then coming along and saying, ‘I’m going to change this with my art.’”

Boon credited his parents with encouraging his interest in music, literature and history: “the beauty of the world”. His mother was particularly supportive, reckoning that it was better that he and Watt were at home practicing than out on the streets. These principles never left them. “The first thing is to give workers confidence,” Watt told Azerrad, “That’s what we try to do with our songs. It’s not to show them ‘the way’ but to say, ‘Look at us, we’re working guys and we write songs and play in a band.’ It’s not like that’s the only thing to do in life, but at least we’re doing something – confidence. You can hear some song that the guy next to you at the plant wrote.” As Boon sings in ‘The Glory Of Man’: “I live sweat, but I dream lightyears”.

The heart of the Minutemen lies in Boon and Watt’s deep friendship. They met in their early teens, bashing out hard rock covers on randomly tuned guitars. Then came the sea change of punk. Following the demise of their quartet The Reactionaries, Boon and Watt were joined by George Hurley, a former surfer who had taken up the drums following an accident. Each one was a brilliant player, combining jazzoid chops with punk economy and speed. “Me and Mike Watt played for years, punk rock changed our lives,” Boon relates on “History Lesson Part II”, Double Nickels’ emotional centrepiece. ‘We learned punk rock in Hollywood, drove up from Pedro. We were fucking corndogs. We’d go drink and pogo.” It’s all here: friendship, the transformative power of art, the tenderness offset by self-effacing humour. “Mr Narrator,” he continues, “this is Bob Dylan to me. My story could be his songs.” This is punk as folk music, by the people, for the people.

Between 1980 and 1983, the Minutemen released two studio albums and four EPs. Each one saw them refining and expanding their template of trebly guitar, grooving bass and powerful, fluid drumming. Animating the angular forms of British post punk with the intensity of hardcore and improvisatory squall of Beefheart and free jazz, they grounded their music with the blue collar choogle of Creedence Clearwater Revival and hard rock of Blue Öyster Cult. Double Nickels was the next leap forward. Spurred on by the news that their friends Husker Du had recorded Zen Arcade – hardcore’s first double album – the Minutemen went on a writing frenzy, working with producer (and former Blue Cheer keyboardist) Ethan James to lay down the new tracks across two sessions in November 1983 and April 1984.

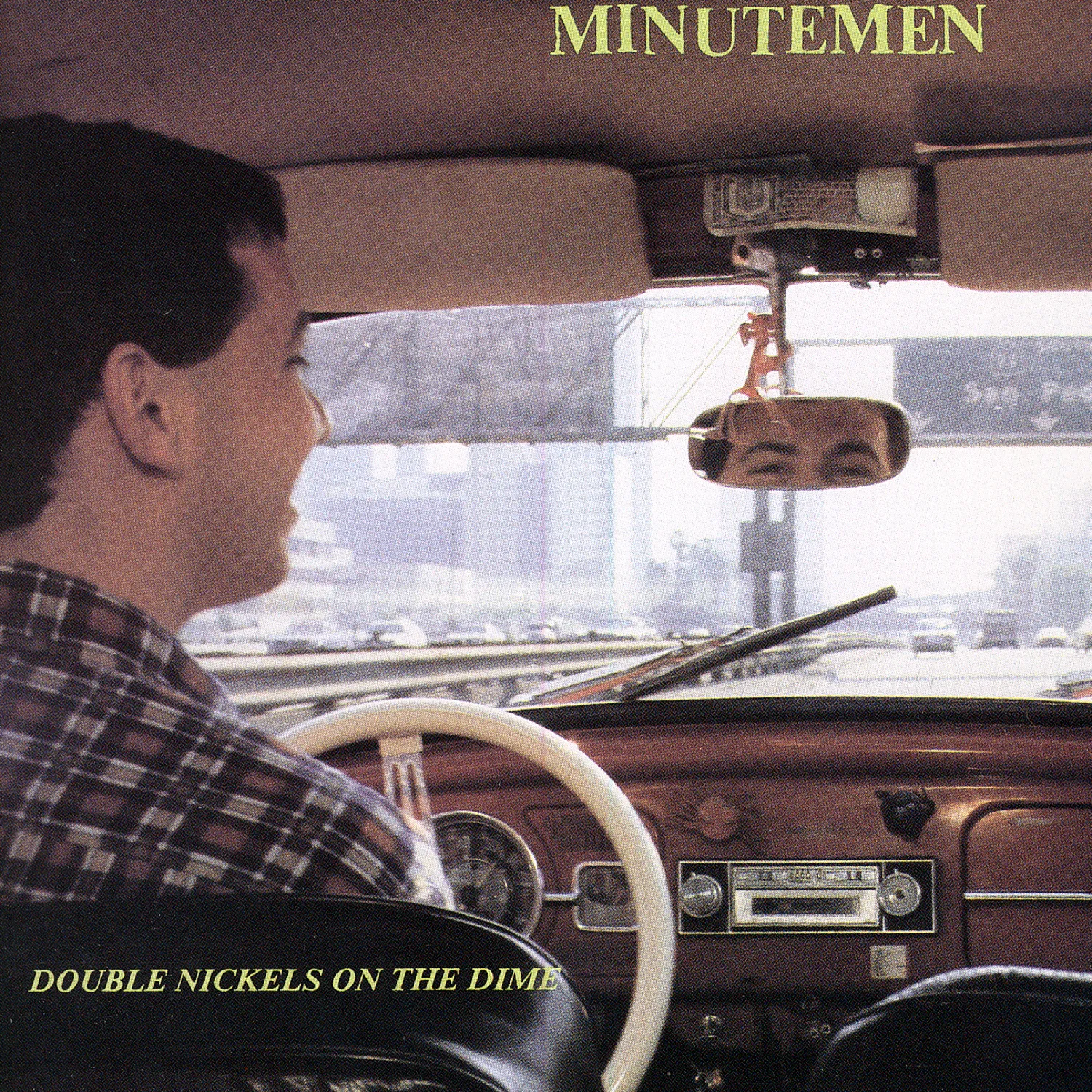

Zen Arcade tells the story of a teenage runaway. Not to be outdone, Boon, Watt and Hurley came up with a concept of their own, although as Watt would later acknowledge, many listeners failed to pick up on the close-knit trio’s in-jokes and references. To break it down, “double nickels” is trucker slang for 55mph. In 1984 hard rocker Sammy Hagar released the execrable petrolhead anthem ‘I Can’t Drive 55’. In response, the Minutemen were, Watt said, “gonna drive safe and make crazy music, while that clown was gonna drive crazy and make safe music.” The album cover depicts Watt driving his VW Beetle at exactly 55mph down Interstate 10 (aka “The Dime” in trucker slang), with a sign for San Pedro coming up ahead. Each side opens with a ‘Car Jam’, where each member revs their engines, introducing a framing device borrowed from Pink Floyd. As on Ummagumma, each member curates a side, with the fourth “Chaff” side comprising the songs left off their individual ballots.

As Fournier’s book already offers a track-by-track analysis, it makes sense to take a more thematic approach. That said, it is worth noting how fantastically sequenced each side is. Each side gives a sense of the Minutemen’s individual personalities and interests, without taking away from the group identity. Boon’s Side D has one of the greatest opening stretches in music history, with three barnstormers then a breather in the form of his gorgeous punk-flamenco guitar solo ‘Cohesion’. From there all bets are off. There’s the low-slung funk of ‘It’s Expected I’m Gone’, the satirical ‘#1 Hit Song’, Joycean spoken word from Watt, a righteous Creedence cover and a ferocious anti-advertising rant. Side Mike features some of group’s catchiest and most experimental numbers, while Side George opens with a free percussion solo before taking in anthemic tunes like ‘Themselves’ and ‘This Ain’t No Picnic’. While less cohesive by design, Side Chaff offers the monumental ‘Jesus And Tequila’ and ‘Little Man With A Gun In His Hand’ alongside proto math-rock instrumentals, boisterous funk and breathless Steely Dan and Van Halen covers. It ends with ‘3 Car Jam’, a punk-Fluxus companion piece to Sven-Åke Johansson’s Konzert für 12 Traktoren and Filipino composer Jose Macada’s unrealised automobile ballet.

You want gleeful scatology with your formal experimentation? Joyce, Boon and Watt have some smoking globes for you. “Big fucking shit, right now, man,” hollers Boon at the end of ‘It’s Expected I’m Gone’, a lyric Watt wrote because he thought it would be funny coming from his buddy. And it is, with the sheer gusto of Boon’s delivery making it oddly righteous. Like Joyce, the Minutemen can be unapologetically intellectual one moment and magnificently crude or silly the next. Inspired by the ‘Ithaca’ chapter of Ulysses, where Joyce adopts the question-and-answer form of the catechism, ‘One Reporter’s Opinion’ has Watt mercilessly taking the piss out of himself. “What can be romantic to Mike Watt? He’s only a skeleton… he’s a dartboard, his sex is a disease, he’s a stop sign”.

Set to chiming acoustic guitars and rumbling bass, ‘Do You Want New Wave Or Do You Want The Truth’ riffs on Joyce, Umberto Eco and Ludwig Wittgenstein by featuring multiple voices exploring semiotics: “Should a word have two meanings… should words serve the truth?” While the title alludes to record industry sophistry, the song itself poses broader questions about how artists can retain their integrity and communicate their truth in a capitalist system. The elegant instrumental ‘June 16th‘ nods to “Bloomsday”, the day on which Ulysses is set, which is also the birthday of SST in-house artist Raymond Pettibon, who introduced Boon and Watt to Eco’s theories. ‘Take 5D’ is less directly Joycean, yet its juxtaposition of the everyday – the lyrics are taken from a landlord’s note about a leaky shower – and a disarmingly pretty weave of electric and acoustic guitars, resonates with the great author’s inversion of “high” and “low” art. Meanwhile, the found lyrics and the outsourcing of guitar duties to Saccharine Trust’s Joe Baiza and Tragicomedy’s John Rocknowski and Dirk Vanderberg, subvert bourgeois notions of individual genius. The Beefheartian coda of scrabbling guitar skronk seals the collectivist deal.

“Music can inspire people to wake up and say, ‘Somebody’s lying.’ This is the point I’d like to make with music,” Watt told Rolling Stone in 1985, “you should challenge your own ideas about the world every day.” There’s no shortage of hardcore songs attacking the Reagan regime, but the Minutemen pull off the rare trick of raising consciousness without being bluntly didactic. There’s no question what side they’re on – no quiescent liberal calls for “nuance” here – but they encourage the listener to think for themselves. Taking their cues from Bob Dylan, The Pop Group and Creedence, the Minutemen’s songs explore the themes of imperialism, war and exploitation of labour.

Boon’s song ‘The Only Minority’, from 1983’s What Makes A Man Start Fires? is as succinct an analysis of capitalism as it gets: “They own the land/ We work the land/ We fight their wars/ They think we’re whores”. Double Nickels picks up the theme with a cover of Creedence’s ‘Don’t Look Now’, John Fogerty’s meditation on invisible labour: “Who will take the coal from the mine… who will make the shoes for your feet?” ‘This Ain’t No Picnic’ draws on Boon’s own experiences of working for a racist boss who wouldn’t let him listen to soul or jazz on the warehouse radio: “Losing my self-respect, for a man who presides over me… I’ll work my youth away, in place of a machine”. Yet he refuses to be cowed. ‘Toadies’ and ‘Little Man With A Gun In His Hand’ continue the theme, showing how capitalism stifles dissent by offering individuals a small taste of power.

An avid reader of history and politics, Boon was under no illusions about the trail of death and destruction left by the US in the name of anti-communism, from South East Asia to South America. One of the Minutemen’s catchiest yet angriest songs – Watt’s bassline slaps and pops like a punk Larry Graham – ‘Viet Nam’ lays out the human cost of the war, listing the number of Americans and Vietnamese killed: “Let’s say I got a number,” Boon sings, “That number’s fifty-thousand. That’s ten percent of five-hundred-thousand.” The closing lines chill: “Was this our policy? Ten long years, not one domino shall fall.” With its furious chicken scratch guitar and grinding bass, ‘West Germany’ extends the group’s analysis to the Cold War, while ‘Untitled Song For Latin America’ addresses Reagan’s funding of right-wing paramilitaries in Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador. A member of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador, Boon pulls no punches: “The western hemisphere and all inside/ We know who’s murdering the innocent… I would call it genocide/ Any other word would be a lie”. Heard today, the song is all too relevant.

Known to many as the Jackass theme tune, ‘Corona’ is in fact one of the greatest protest songs ever written. “The people will survive/ In their environment,” sings Boon, expressing solidarity with the people of Mexico. Reflecting on the band’s day trip to a Mexican beach on July 4th 1982, Boon surveys “the dirt, scarcity and emptiness of our south”, a result of “the injustice of our greed, the practice we inherit”. A woman passes him on the beach: “I could see it in her eyes.” All he has to offer her is an empty Corona bottle with a five-cent deposit. This small human moment brings the group’s broader political analysis into focus. And the music is glorious, its twang and bounce referencing country, polka and neo-norteño.

The Minutemen followed Double Nickels with the Project Mersh EP and their final studio album, Three Way Tie For Last. Both releases saw the band continuing to experiment while delivering anthems like ‘King Of The Hill’ and ‘Courage’. Tragically, Boon’s death in a car accident in December 1985 cut the Minutemen off in their prime. Watt has gone on to do many great things, from forming fIREHOSE with Hurley and guitarist Ed Crawford, to jamming econo with The Stooges, Petra Haden and Il Sogno Del Marinaio, but the chemistry he had with Boon is a once-in-a-lifetime phenomenon. With Double Nickels, the Minutemen showed, in the most generous terms, what punk could be as a model for art and living. As Boon says in ‘History Lesson part II’: “Our band could be your life”.