“At the end of it all, it was difficult to decide which was the more romantic, the more exciting: the real man or the myth he has become.”

Colin F Cave, Ned Kelly: Man and Myth (Cassell Australia, 1968)

The above quote was written by Nick Cave’s father Colin, and taken from an introduction to a book about Ned Kelly. Mark Mordue opens his excellent Nick Cave biography Boy On Fire (Allen & Unwin 2021) with it, and it holds true not just for the notorious Australian outlaw, but also for Cave Junior.

Colin Cave was a man of words, an inspirational teacher of literature and drama, who died in a car accident when his son was 19. Cave found out about his death while being bailed from prison for burglary by his mother – the gap between the man who read him Lolita as a child and his errant son none more stark. A cod psychological reading might suggest that Cave’s desire to position himself as a literary figure as well as a musical one was driven by this loss. But the truth is that when Cave left The Birthday Party in 1983 to launch a solo career, the general consensus was he was unlikely to make to the end of the year let alone become a respected man of words. One music paper ran a sweepstake as to who would be the first to die, him or Keith Richards. In 1983 Nick Cave was not regarded as a serious contender.

That opinion wasn’t just held by the music press. Despite now being regarded by some as simply Cave’s ‘old band’, The Birthday Party was a group of distinct personalities, all vying for the spotlight, both onstage and off. Cave often found himself overruled and even bullied by other members, particularly by guitarists Mick Harvey and Rowland S Howard. It was such tensions – and Cave’s eventual refusal to work with co-writer Howard – that split the band after a final Australian tour.

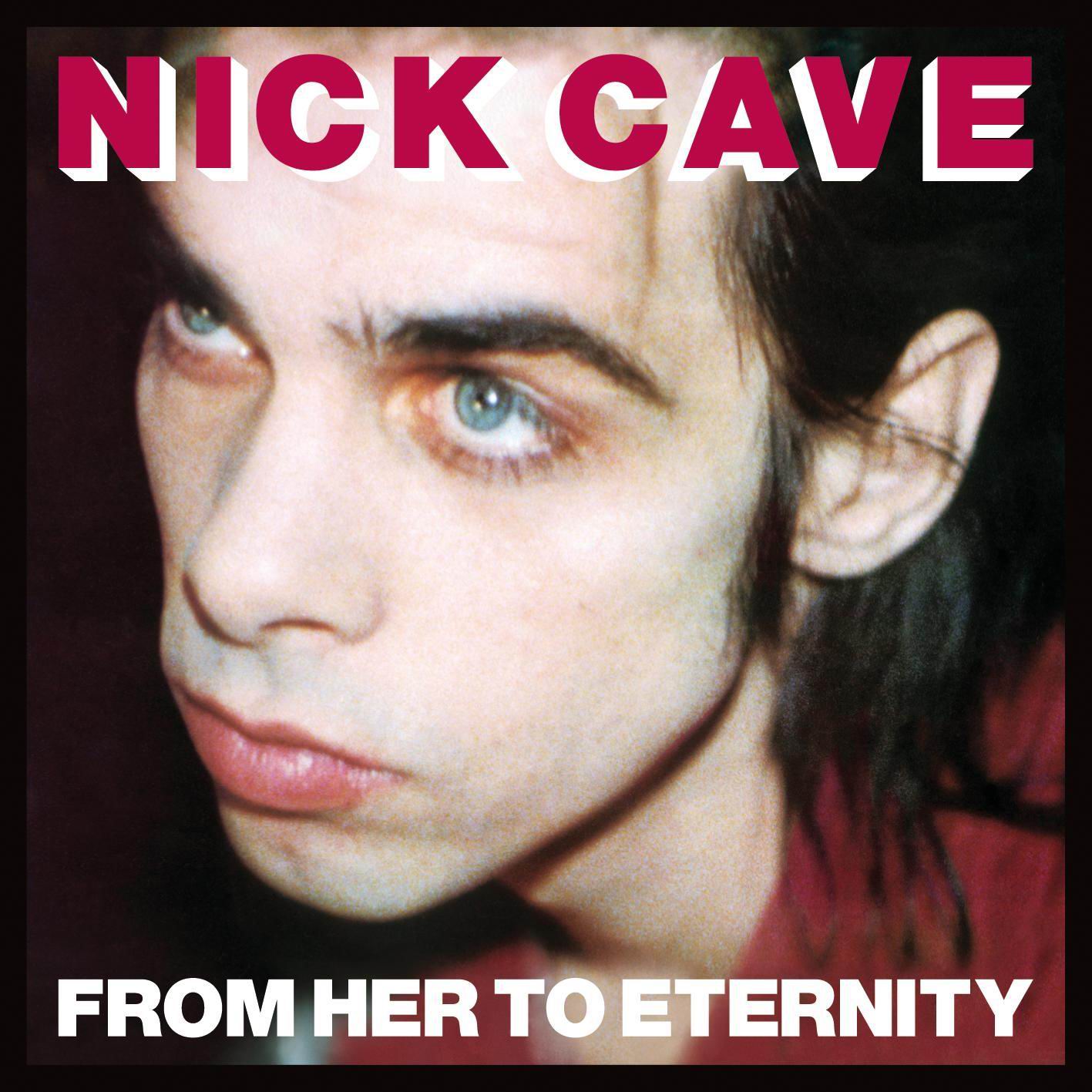

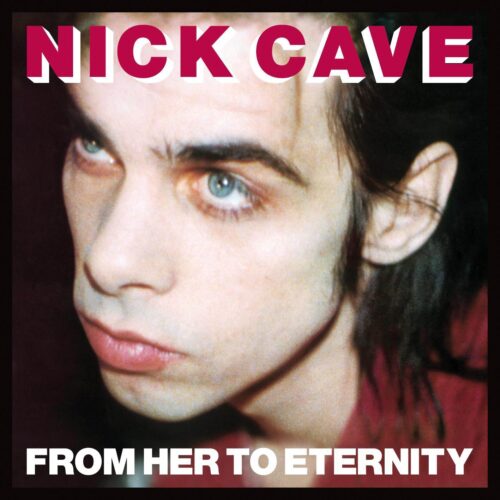

Yet despite gaining freedom from his antagonists, the first person Cave contacted to work on new material was – much to his surprise – Harvey. And after a few false starts and band names – including at one point Nick Cave, Man or Myth? – a line-up coalesced around the two Australians that included Einstürzende Neubauten’s Blixa Bargeld, former-Magazine bassist Barry Adamson, and former-Plays With Marionettes guitarist Hugo Race. Another contributor – and briefly a member of the band – was Cave’s on-off girlfriend and collaborator Anita Lane. A talented artist in her own right, Lane had not only written material for The Birthday Party but she would also go on to co-write some of Cave’s greatest songs. “She was the smartest and most talented of all of us, by far,” Cave wrote on the occasion of her death in 2021. And so it was this group of disparate elements that in March 1984 entered Trident Studios in Soho, with in house engineer Flood, to record the first Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds album, From Her To Eternity.

Cave’s intentions for the record, channelled through Harvey, was to create work that was slower, more spacious, and lyrically driven than the music produced by their former band. Having Bargeld on guitar was an inspired choice. An avowed anti-musician, the German had spoken of his hatred for the instrument in several interviews, and expressed this disdain by attaching an extra string to a nail in the headstock that produced an untuneable drone every time he hit it. The avant garde sensibility that Bargeld brought to the proceedings was key and it’s easy to imagine the album falling into a far more traditional pastiche of Cave’s then musical obsessions – gospel and the blues – without his caustic contributions. As it was, the record strives to create a new music from several old ones, a process that Cave also applied to his lyrics. The more narrative approach meant that he could reference, and in some instances channel, his literary heroes. Despite being regarded at the time as simply a junkie Lux Interior, Cave was determined to remake himself in the mould of Mark Twain, Herman Melville, and William Faulkner, no matter how controversial his slavish dedication to them may be.

It wasn’t just his literary heroes Cave was paying tribute to either. After reading Albert Goldman’s Elvis (Viking, 1981), Cave had become obsessed with the King, particularly the latter years of his life, and released a version of ‘In The Ghetto’, around the same time as From Her To Eternity. This cover didn’t make the album, but Cave chose to open the record with another, a version of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Avalanche’ from his 1971 Songs Of Love And Hate album. Cohen’s stock was low in the early 80s, his I’m Your Man renaissance still a few years off, and if he was ever mentioned in the press, it was as shorthand for a kind pseudo-poetic bedsit miserabilism. Cave’s take on Cohen was more visceral, and he used the song to comment on his relationship with his audience, and their expectations of him. “I am on a pedestal, you did not raise me there” Cave spits, “Your laws do not compel me now, to kneel grotesque and bare”. Cave asserts his authority, outlining his position as an artist as he sees it: indifferent to the norms of society, in fact exempt from them all together. A theme he would return to – and test – before the album was through.

Despite being a veteran of working on ‘challenging’ records by the likes of Marc & the Mambas, Test Dept and Cabaret Voltaire, Flood had his hands full with Cave and his charges. “It was quite unlike anything I’d done before” he said. The hard drug use by certain musicians was one aspect of it, although that soon became part of the process – according to Adamson, the producer named a certain area in the studio ‘diabetics’ corner’ for obvious reasons. The claustrophobia of the studio is reflected in the lyrical themes of the album, of being trapped in a confined space, where there is no air, no freedom. This is none more apparent than on ‘Cabin Fever’, where Cave casts himself as Captain Ahab in Melville’s Moby Dick. A thinly veiled account of his life with his then partner Anita Lane in their cramped Brixton flat – “The Captain’s arm like a bunched-up rope, and Anita wriggling free on a skull and dagger” – getting it on tape had been attempted twice when Cave announced, the night before the finished album was due to be delivered, that it needed to be done again. The atmosphere created by the impending deadline turned fractious, and Cave was kicked out of the studio while the track was being mixed. He eventually returned at 6am, professed his love for the results and the people who created it, and then the album went off to Mute’s production plant.

Despite the risks being taken in the studio, the label were only ever supportive of Cave’s methods and madness. “Nick wanted a more narrative style, epic kind of tales,” said Mute boss Daniel Miller. “I was fascinated how it was going to turn out. I just let them get on with it, almost more than any other band on Mute.”

For a label best known for the electronic sounds of the early 1980s, it’s quite a leap from the synth pop of Depeche Mode and Yazoo to the chain gang call-and-response of ‘Well Of Misery’, a humorous death-knell lament, built around Adamson’s dolorous bass line. The bassist again takes centre stage on the title track, his low thrum reminiscent of Suicide, while staccato piano adds to the tension. Throughout Bargeld’s guitar leaps violently out into the room before scurrying back towards the skirting boards. The lyrics had been co-written with Lane six months before, and tells the story of a man brought to distraction by a crying girl in the room above. Cave describes hot tears, “Leaking through the cracks, down upon my face,” and catching them in his mouth. The desire to possess the girl is almost unbearable – a “wound” – yet the protagonist knows that once that has been attained, the desire gone. The leap in imagination from Cave’s previous work is striking, and in ‘From Her To Eternity’ he created his first post-Birthday Party classic, a song that remains in the band’s set to this day.

The first track recorded for the album – and therefore the first ever Bad Seeds song – ‘Saint Huck’ is another example of Cave reaching for literary status. Transposing Mark Twain’s intrepid adventurer Huckleberry Finn into the urban jungle, it outlines his corruption by the various temptations and deprivations on offer. It doesn’t end well for Huck – “A smoke ring hovers above his head… and the men all came, and put a bullet in his eye”. Cave’s decision to emulate the (at the time) century old novel’s American literary regionalism created tensions in the Bad Seeds, particularly – and understandably – with Adamson.

“When he gets to the line ‘a bad-blind n****r at the piano,’ I throw the magic boomerang and step back to compose myself,” wrote Adamson in his memoir Up Above The City, Down Beneath The Stars (Omnibus, 2021). “After a few deep breaths I make out like, ‘Hey, I’m with you guys, ABC, man. Always Be Cool.’ The truth is the bottom has just fallen out of my stomach. I scramble for justification of that word being used in front of me.”

Adamson also wrote about playing the song live, and Cave singing the slur in front of him: “I feel as though the whole room is pointing at me. I stand alone. My flaming hubris and I. It is quite a moment.”

Cave stopped playing ‘Saint Huck’ in 1989, but resurrected it for 2001’s No More Shall We Part tour, racial slur intact. Watching footage of those performances, as Adamson pointed out, there’s an undeniable charge as Cave approaches the line – both idiomatic and literary – but that still doesn’t justify the use of the word. That it’s being performed by a the exclusively white 2001 iteration of the Bad Seeds only adds to the queasiness.

The song hasn’t appeared in the set since, although Cave has returned to the idea of a literary naif lost in the big city with the high camp of 2007’s Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! but it’s not a patch on ‘Saint Huck’. Should he ever resurrect the song, Cave is clear as to whether linguistic sensitivities would have him self-censor. Answering a question on his Red Hand Files website in 2020 (seemingly from another artist familiar with transgression, Gavin Friday of Virgin Prunes), he said, “Perhaps we writers should have been more careful with our words – I can own this, and I may even agree… but what songwriter could have predicted thirty years ago that the future would lose its sense of humour, its sense of playfulness, its sense of context, nuance and irony…” Recently Cave seems to have doubled-down on his more transgressive modes of expression. “I was raised to see that art was something that got up people’s noses, that confronted people, that challenged people, that pushed people out of their complacency – these were self-evident virtues,” he told The Louis Theroux Podcast in 2023. “So the idea that our music, our art, is to be defanged in this way, does raise my hackles to some degree.”

Cave again courted controversy with ‘Wings Off Flies’ although this time it was his love of winding up journalists that drove him. A co-write with fellow ex-pat JG Thirlwell, the music for this misanthrope’s tale of thwarted love was written at Lydia Lunch’s West Kensington flat. The title came from a song by an old Melbourne friend of Cave’s, Peter Sutcliffe of The Models, who was duly credited. Several journalists picked up on Sutcliffe sharing a name with the UK serial killer The Yorkshire Ripper, a misunderstanding that both Cave and Harvey encouraged at the time. “He helped write the lyrics for that before he got caught,” he told punk fanzine Dangerous Rhythms. Cave’s disdain for journalists was legendary, yet it seemed to be the symbiotic nature of his relationship with the press that irked him the most. He was more than aware of how important good copy was to help create the artist he wanted to be, but that didn’t mean he liked it.

“He’d built up a huge sense of his own mythology and he was becoming aware of that possibility towards the end of The Birthday Party,” said Howard. “That he could say things in interviews and the point wasn’t whether they were true or not, the point was what they revealed about him.”

Cave has always attempted to control his own narrative, and of late has taken ownership of it almost completely. Starting with 2014’s staged documentary 20,000 Days on Earth, through 2016’s One More Time With Feeling and culminating with his Red Hand Files website and the book Faith, Hope And Carnage (Canongate, 2022), these days Cave for the most part circumnavigates the press. Yet as Howard says above, Cave was always cognisant of framing his own narrative, and a reading of From Her To Eternity’s closer ‘A Box For Black Paul’ can be seen as an early example of this. The song was first aired at the notorious Immaculate Consumptive shows Cave played with Lunch, Thirlwell and Marc Almond in New York and Washington DC at the end of 1983. The song had grown from those performances – where Cave never managed to get to the end – into the near ten-minute dirge that appears on the album. Over funereal piano and recalcitrant guitar, Cave bemoans the demise of the titular Black Paul, and how in death he continues to be misrepresented and misunderstood. Despite claiming the contrary – “It never occurred to me, but such are the mysterious and happy accidents of songwriting,” said Cave – the song is a thinly-veiled eulogy for his former band; the BP of Black Paul being a lyrical proxy for The Birthday Party.

Black Paul is stood “up against the stoning wall” by an ignorant audience, while the “scribes with their poison pens” gather around the headstone to report the facts as they see fit. Switching to the first person for the final verse, Cave states his soul will never rest until a box has also been built for his ‘gal’ – the description, “red dress and long red hair hangin’ down”, matching that of Lane. Such fusion of fiction, truth, multiple narratives, and old or Biblical language would become Cave’s stock-in-trade for the next decade, but ‘A Box For Black Paul’ is his first truly successful attempt.

When From Her To Eternity was released on 18 June 1984 it received almost universal acclaim, with the NME calling it, “one of the greatest rock albums ever made.” Although decades later Cave would move away from this style of songwriting – he spoke to Interview in 2013 of the “tyranny of the narrative” – to the magic realism of his recent releases, there’s no doubt that his literary aspirations found nascent form on From Her To Eternity. By the end of the decade he’d published his first novel, And The Ass Saw The Angel (Harper Collins, 1989), with screenplays, lectures and long-form essays to follow. His second novel, The Death Of Bunny Monroe (Cannongate), was published in 2009. Colin Cave would have been proud.

Despite recent tragedies in his personal life reconfiguring Cave’s public persona yet again, he retains a tight grip on his narrative. Back in 1984 Cave wanted to escape the straight jacket of his former band and be recognised as a man of words, with a language all of his own. That he’s achieved this is beyond question, but at the distance of four decades, and with all his artistic achievements considered, it may well turn out that Nick Cave’s greatest literary creation is himself.