”In France, I’m an auteur. In England, I’m a horror movie director. In Germany, I’m a filmmaker. In the U.S., I’m a bum.”

John Carpenter

They Live premiered in theatres across America in 1988 just days before a general election. In keeping with its self-awareness as a piece of metafiction, it blurred the boundaries between the comic world from whence it came, and the real world it was about to impact upon, alluding with a wink that all might not be well with America. Its promotional poster read: “You see them on the street. You watch them on TV. You might even vote for one this fall. You think they’re people just like you. You’re wrong. Dead wrong.”

Having completed two full terms, president Ronald Reagan wasn’t standing again, but his successor, his vice president George Bush, offered more of the same voodoo economics and rugged individualism, a continuation of the radical agenda brought in by the Reagan administration to deal with a prolonged period of stagflation. Even in the 1960s, conservatives who remembered the Great Depression couldn’t countenance the idea of abandoning Keynesianism – Richard Nixon included – but a couple of generations on from the 1930s the shackles had been removed with a vengeance. The tax breaks for the wealthy, the streamlining of social spending and increased military spending, the deregulation of domestic markets and the championing of entrepreneurialism above all else was helping to widen the gap between the haves and have nots.

John Carpenter was never likely to influence the result of the election with one movie. His influence has always been felt more acutely across the Atlantic, impacting upon everyone from continental philosophers to French synthwave hipsters – something we’ll look at in more detail later. Made with an estimated $4 million budget, They Live recouped nearly $5 million in its opening weekend at the US box office according to Imdb; a great return for a picture with a relatively small outlay. They Live didn’t anoint the hapless Michael Dukakis as the 41st President of the United States, but its arrival at such a critical juncture – at the time of an election that could have been a moratorium on the Reagan years and a chance to moderate long-term fiscal damage – adds gravity to the film’s growing reputation as a work of great prescience. This was the moment where Reagan departed and his legacy began, and a third term for the Republicans set us on a course America has never recovered from.

“Basically what our spin on the story is is that all the aliens are members of the upper class… the rich,” Carpenter said at the time. “They’re slowly exploiting the middle class and everyone is becoming poorer. And everything we think about buying cars and having pools and condos and all the things that everyone strives for in America, [these things] are being created by this race of inhuman creatures that want to exploit us like a third world. And it’s told from the point of view of the homeless. So it has a theme and a message to it, but basically it’s an action film.”

An action film starring professional wrestler “Rowdy” Roddy Piper – who Carpenter apparently met at Wrestlemania III – as itinerant labourer John Nada. Nada uncovers an insidious alien network that’s ruthlessly running the world for its own ends. The down-at-heel hero stays at a homeless shelter in Justiceville, where he’s recently arrived in search of work. The first sign of resistance against an unseen enemy comes through the television set: “They are dismantling the sleeping middle class,” warns the interloper in a transmission overriding the scheduled programming. “More and more people are becoming poor. We are their cattle. We are being bred for slavery…"

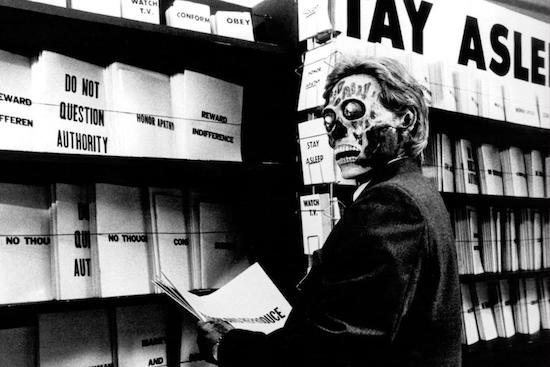

It all becomes clearer when Nada stumbles across a box of sunglasses hidden in the church next to the shelter. When he puts them on, they become a kind of ideological rosetta stone, revealing the subliminal intentions behind all the slogans that surround him (and us) like wallpaper. Stripped of the advertising obfuscation, they become naked commandments: “Obey”, “Consume”, “Marry and Reproduce”. These aren’t just any old Ray Bans; they’re Hoffman Lenses, developed by freedom fighters of the resistance to allow wearers to see the world behind the world, revealing the true purposes of the established order. Furthermore, Nada is suddenly able to see aliens masquerading as civilians when he puts on the shades.

So far, so paranoid, thought reviewers at the time; dismissing They Live as a hypermasculine schlockfest riffing on the “old chestnut of subliminal conditioning” (The Times). “Mr. Carpenter has directed the film with B-movie bluntness, but with none of the requisite snap,” said The New York Times. “All in all, an entertaining (if ideologically incoherent) response to the valorisation of greed in our midst, with lots of Rambo-esque violence thrown in,” said The Chicago Reader; while The Washington Post said: “Even for sci-fi, the creatures-walk-among-us plot of They Live is so old it ought to be carbon-dated. Oh, sure, director John Carpenter trots out the heavy artillery of sociological context and political implication, but you don’t have to get deep down to realise he hasn’t a clue what to do with it, or the talent to bring it to life.”

In the 21st century, Carpenter’s commentary on the invisible nature of capital has come to be regarded as far more astute than critics gave it credit for at the time, especially amongst academics. As wealth disparity widens, it’s as if people have begun to reach for the proverbial Hoffman Lenses in desperation, and now see the subversive where they once saw a hammy B-movie. “When you put the glasses on you see dictatorship in democracy. It’s the invisible order, which sustains your apparent freedom,” said Slavoj Žižek in The Pervert’s Guide To Ideology (2012), adding that They Live is “definitely one of the forgotten masterpieces of the Hollywood left.” Film professor Kenneth Jurkiewicz has also identified Nada’s symbolic adversaries as the “implacable forces of rampant, merciless Reaganomics”, and Christos Kefalis called it “the Marxist movie par excellence,” in an essay called ‘When Science Fiction Meets Marxism’.

“The film endorses the call-to-arms of the Communist Manifesto,” wrote D. Harlan Wilson in his book They Live (Cultographies) in 2014. “Proletarians must rise against and quash their bourgeois masters with an eye to accomplishing class equality in the not-too-distant future. Violence paves the way to class equality. Nada is a symbolic prole who, in the end, uses violence to single-handedly overthrow the alien bourgeois capitalists by exposing them for what they are.”

Similarly, many critics have dismissed the “long drawn-out fist fight” where Nada tries to make his workmate Frank Armitage (Keith David) wear the shades, though Wilson sees an implicit, microcosmic nod to racial tension in America. (The scene between the pair is heavily choreographed, gratuitously violent, lasts for more than five minutes and has become the film’s cult calling card). “Armitage’s obduracy becomes much more than a means for Carpenter to stage a lengthy brawl,” writes Wilson. “Nada converts into the white master attempting to force his viewpoint onto the black slave. He may be trying to educate Armitage, rather than keep him ignorant and ‘happy’, as was the custom of most Antebellum slave owners who disallowed their slaves from learning how to read.” Zizek on the other hand interprets it as the pain that comes from not giving in to capitalist impulses: “Ideology is our relationship to our social world. We, in a way, enjoy our ideology. To step outside of it is painful.”

Though Carpenter has often spelled out the purpose behind his most political film, it didn’t stop neo-nazis either misinterpreting or wilfully expropriating its message and twisting it for their own ends a few years ago. “[They Live is] giving the finger to Reagan when nobody else would,” he stated in 2013. “By the end of the 70s there was a backlash against everything in the 60s, and that’s what the 80s were, and Ronald Reagan became president, and Reaganomics came in.” In 2017, Carpenter dismissed the antisemitic canards and conspiracy memes doing the rounds, all of which attempted to lay claim to his film. “They Live is about yuppies and unrestrained capitalism,” he tweeted, furiously. “It has nothing to do with Jewish control of the world, which is slander and a lie.”

While not exactly a pariah in his home country, his outspoken utterances and his siding with the left has unsurprisingly alienated sections of his fan base. His socialist leanings, and also his mesmerising synthcore soundtracks, have played well with a European audience though. Carpenter has been on tour recently, and a review for this very website by Repeater novelists Tariq Goddard and Carl Neville, gave thanks for his monumental contribution to culture: “This kind of show is pitched somewhere in attitude and ambience between the convention and the lifetime achievement section of an award show, a montage of greatest moments while the artist soaks up the applause, more a valedictory lap of the stadium than a tour. Inevitably, they carry certain poignancy, both for the artist’s advancing age, the appreciation of a younger age group, and the mourning of a past that allowed space for such wayward figures to uncompromisingly express their impulses.”

Carpenter’s waywardness and lack of compromise has found a new generation of admirers now he’s into his 70s, and there’s nowhere that’s truer than in France. When I met his gallic contemporary Jean-Michel Jarre in 2015, he spoke of the excitement he felt collaborating with Carpenter on his Electronica project: “He’s a brilliant filmmaker and he’s a brilliant musician, and he did all of these soundtracks with synthesisers. It’s a unique situation in the history of synthesisers and the movie industry; especially Hollywood in those days. The classic thing then was a symphonic orchestra with strings John Williams-style, and he’s an absolute cult figure for DJs as you well know. It’s one thing to do soundtracks, and another thing to use synthesisers, but another thing altogether to have a recognisable style. You listen to John Carpenter’s music and you know it’s John’s immediately.”

Several Parisian-based artists have overtly paid tribute to Carpenter in their music this decade, including Poitiers synthwave exponent Carpenter Brut, cult Gonzai signings Blackmail, and most significantly Zombie Zombie, who covered five of his theme tunes on a 2010 EP (Zombie Zombie Plays John Carpenter). Carpenter Brut took his name from the champagne J. Charpentier Brut, then shortened it in homage to the American auteur. “For me it is difficult to separate the producer from the composer, because what I like about John Carpenter is his artisanal spirit,” he says. “The fact that he is the master from the beginning to the end of his projects, without making too much compromise, has always forced my admiration.” He adds that while Carpenter is a big influence on the French synthwave movement, Kavinsky and Vangelis are just as important.

Cosmic Neman of Zombie Zombie says when he and Etienne Jaumet started buying second hand synths, they realised that they could replicate the sounds from the films on the instruments. “We noticed we could make the same sounds as John Carpenter’s scores, and we began to understand how he made the soundtracks of his movies; just a bassline with a drum machine and a simple melody. He taught us how to be efficient by making it simple and minimal. He redefined horror movies soundtracks.” Blackmail’s 2016 album Amore synthétique was written in direct homage to Carpenter, a fact that band member Stéphane isn’t about to deny. “Every time I’m in front of a synth, the first thing that comes to me is the urge to play the riff from Assault on Precinct 13. It’s the equivalent of the riff to ‘Louie Louie’ on the guitar.”

Other admirers of the film director include French DJs Scratch Massive, Parisian dance maverick Flavien Berger and cosmic Belgian instrumentalists the Loved Drones. Sebastien Chenut of Scratch Massive says that while he prefers Tangerine Dream, he’s impressed by Carpenter’s innovation in the face of adversity: “He wasn’t intending to make a soundtrack at first, but when he didn’t have the budget for Assault On Precinct 13 he decided to make his own, and it just so happened that that soundtrack was brilliant! But that wasn’t his choice, it was a solution.”

“I can hear his music in many of my fellow artists,” says Flavien Berger. “Turzi, Zombie Zombie and even Palmbomen II, who I’m very fond of. What sounds Carpenter-like is not simply one type of instrument, it’s more of an approach: sort of a melancholic mood when something sounds disintegrated.”

“Carpenter is an underestimated composer,” says Benjamin from the Loved Drones, who also rates They Live as one of his favourite films. “It’s definitely a masterpiece. Like good wine, the film has matured and still tastes good in 2018. It’s much more than a B-movie; it’s a radical political film against the powers of neoliberalism.”

“It’s a prescient work of monolithic importance,” says his bandmate, Brian. “I can’t believe they allowed him to make it. Carpenter saw the writing on the wall and voiced his fears through his art.”