GAS photograph by Michal Rasmus

”A man’s work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.”

Not my words of course, but those of Albert Camus. Written down this might look like a pretty statement, but it doesn’t ring true to me, and scans like the slogan on an inspirational cat poster. However, if I could be so bold as to switch the word "images" out for the word "sounds", suddenly I’m having it. It feels like I’m getting somewhere.

If I concentrate hard I can hear the light hiss of rainfall hitting leaves at night time. It has a peculiar flavour. One that I don’t have a word for. I’m walking away from a standpipe screwed to a post on a waist-high wooden fence, with the edge of a forest glowering just behind it. My brandless, bright-red tracksuit bottoms are wet from the ankles up to the knees and my brandless, rubber-soled trainers are squeaking against wet, uncut grass. The 25-litre jerrycan strapped to a trolley is sloshing with each step back toward the touring caravan. My grit-toothed determination not to look over my shoulder at the forest edge crumbles each time there is a loud creak or rustle behind me. Finally I reach the caravan. There is the longest of zips, I step inside, then a thud of kicked off trainers hitting canvas awning walls. There is a satisfying clunk and click of the tourer van’s door opening to allow me entry and then closing behind me. Threat is replaced by the sweet sounds of safety and relaxation. A long duration shhhhh from the gas fire, the bubble of Goblin tinned meatballs in gravy on the two ring hob and the persistent rattle and patter of northern rainfall hitting aluminium roof.

And, now, when I listen to noise or ambient or industrial or techno ["expensive static" © Louis Pattison], and find myself asking, “Why do I like this? What good is this music?” perhaps I actually have an answer. It is an echo of the soundtrack to a dopamine and adrenaline flooded, night time walk along the edge of the forest and it has stayed with me for four decades.

One of the stranger performances at this year’s excellent Unsound festival dredges up childhood memories of the sound of rainfall and a walk along a forest edge. The Lithuanian composer and sound artist Arturas Bumšteinas has been working with Baroque sound machines for the last five years and Bad Weather is his most complex and well-realised work with them to date. The machines are exact replicas of 17th century devices which were used in European theatres to create the sound of precipitation, wind and more during performances which is – to a certain degree – what they’re being used for tonight.

Bad Weather photograph by Cricoteka

At first there is too much information to process. As well as the shock of the electro-acoustic machine noise itself (some of the speech and weather sounds are being recorded, processed and then amplified in real time), the stage, which is behind two translucent mesh screens, looks like a building site, with piles of rubble, rolls of fabric and sacks everywhere. Librettist Ivan Cheng reads spoken word in staccato manner, studded with lyrics plucked from Phil Collins, David Bowie and Cyndi Lauper songs as his words flash up simultaneously on the mesh. It’s a very clever trick that let’s you know exactly how well rehearsed Bad Weather is but what with the sound design, the dynamic lighting, the contemporary dancers who move about behind him and the oddness of machines themselves, it’s hard to suss out if there’s much in the way of depth behind this hectic avant performance.

But a switch happens. A switch comparable to the Club Silencio scene in Mulholland Drive. When Cheng stops reading we are treated to an intensive demonstration of exactly what these wood and metal contraptions can do. Rocks thrown against a metal sheet covering a wooden box simply become the vicious whip-cracks that accompany lightning. A wooden mace held against a hand cranked flywheel creates blowy gusts. A large cabinet suspended off the floor by a pivot becomes distant rolls of thunder when tipped from side to side (presumably it’s full of rocks). And as a sack of gravel is tipped from above head height onto a long sheet of wood, I close my eyes and – bingo! – it’s 1978 and I’m back in my parents’ caravan as the endless rainfall of my childhood drums on the roof.

It’s not just clever vintage foley though. Bumšteinas initially used ancient weather maps as a visual guide for his ‘musicians’ (who include sound artist Gailė Griciūtė), as if he were some kind of meteorological Cornelius Cardew and this debut performance is well-suited to this Polish festival because it is generally accepted that the first ever weather diaries were kept in Krakow. But as his players became more adept at mastering their instruments – and they can now make nearly any weather sound you could mention (plus many more you’d have trouble describing) – they abandoned their atypical score. So the performers are not making sound effects per se; what they are doing is more analogous to accomplished jazz musicians improvising their way through a well-known standard.

There is an urban myth, a possibly problematic or racist idea even, that the Inuit have 50 words for snow. (They don’t. They have a very reasonable two.) But after tonight’s performance I feel like everyone should have at least fifty words for rain. Cheng reads again toward the end of the outstanding hour long performance and, now attuned to what the ensemble is doing, it becomes clear that this is not a wilful act of pretentious weirdness or a comment on climate change but really about his experiences as an immigrant. The bad weather that is currently spreading across the globe is one of the few things that is not expected to respect borders.

BNNT photograph by Michal Rasmus

If you went to see The Cure during the mid-80s, thunderous post punk anthem and main set closer ‘A Forest’ could last longer than the average Jesus And Mary Chain or Minor Threat gig. The stormy three note bass line coda would always stretch out towards nothing. Again and again and again.

”While the Birthday Party literalized [a] return to the Blues… The Cure, like the Banshees went to the other extreme. Maintaining fidelity to post-punk’s modernist imperative (novelty or nothing), they preferred a sound that was ethereal rather than earthy, artificial rather than visceral. You can hear this in [Robert] Smith’s guitar, which, swathed in phasing and flange, destubtantialized and emasculated, aspires to be pure FX denuded of any rock attack. (Is this the first step towards MBV’s honeyed amorphousness?) The Cure’s version of Blues enjoyment-in-the-frustration-of-desire is auditioned in ‘A Forest’: the song in which the group find themselves, ironically, since it is a song about loss – or rather about an encounter with what can never be possessed. ‘The girl was never there’, Smith sings, a line worthy of Scritti – or Lacan. ‘Running towards nothing…. Again and again and again….’, Smith — a suburban Scotty seeking his Madeleine — pursues the desire-chimera, the petit objet a, through a dreamscape vividly sound-painted by oneiric synthesizers, drum-machines and Smith’s FX-saturated guitar. ‘A Forest’ was the trailer for Seventeen Seconds, and it turned out to be the album’s centerpiece.”

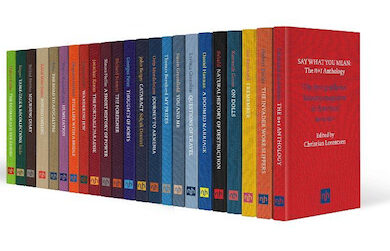

Not my words of course but those of the cultural theorist Mark Fisher (blogging here as K-Punk) who died earlier this year. An enjoyable, respectful and engaging panel intended to be an introduction to his life and work is headed up by Derek Walmsley of The Wire and features writers Lisa Blanning and Agata Pyzik and producer Lee Gamble. They have a lot to cover in an hour or so, including accelerationism, communism, Capitalist Realism, post punk, Russell Brand, hauntology, jungle and depression. Pyzik makes the point that despite his refined taste, Fisher was a populist (quoting his love of The Jam rather than The Cure but still you get her very important point.) Gamble is (from my POV as someone whose formal education ended while he was still a teenager) an essential panelist to give a fuller picture of Fisher; who despite his towering reputation and intellect was approachable and (in my limited experience of him at least) opposed to elitism. The DJ/producer is a working class autodidact from the West Midlands and came to his writing not via a university course but by relatively unmediated methods: googling (the drum & bass label) Metalheadz and (the French philosopher) Deleuze and getting just one hit. (“You’d get more than one hit now”, quips Gamble, referring to how influential Fisher has gone on to be.) Blanning, who knew Fisher for a very long time, says that one of the main projects he had been working on at the time of his death, Acid Communism, may have gone on to be seen as a companion piece to Capitalist Realism. And hopefully this material will still make something of an impact. Within days of this panel, Repeater books announced plans to publish an anthology of his work in 2018 including this fascinating sounding material.

The theme of the 15th edition of Unsound festival, held annually in Krakow, is “flower power”. It ostensibly celebrates the half-century that has passed since the summer of love and all of its multiple promises, successes and failures but the theme is open-ended enough for a wide range of interpretations. Arguably this year’s theme is too wide because even by restricting my review to just one facet of flower power, the idea of the forest, it’s obvious that a very wide range of interpretations indeed is possible. Musically, I hear a lot of evidence that the forest is simply a blank canvas onto which artists can project pretty much whatever they like, almost to the point of metaphoric uselessness.

Bliss Signal photograph by Theresa Baumgartner

We are, of course, spoiled for electronic dance music over four nights at the former communist era hotel, now nightclub complex, The Forum. When I push desperately through the oppressive sonic realm created by Bliss Signal, which is Jack Adams (Mumdance) and James Kelly (Altar Of Plagues/WIFE), I am impressed by the obliterating heaviness that is keeping nostrils all through the main room pinched shut. But even after five minutes exposure, the tightly packed trunks and knot of branches manufactured by this new collaboration reveal themselves to be all but impassable – perhaps such an imposing mesh of sound will take several attempts to penetrate. This music, a very modern take on black metal, has clear arboreal roots as does Rainforest Spiritual Enslavement. But what useful sonic links can be drawn between them? The live debut of Dominick Fernow’s latest project reveals something altogether more spacious and dub influenced than either his work as Prurient or Vatican Shadow. The sumptuous, titular field recordings act as exquisite balance to icy cold wave synths. Fernow’s refusal to talk about his work (especially given how serious sounding, bordering on po-faced, it can be) attracts a lot of projection (some of it in turn wild conjecture and close to hysterical) but tonight’s mix of scornful digital dub and ambient techno initially looks like it will commit the cultural crime of being dull rather than being politically problematic. It unfurls slowly into something that packs an astonishing hypnotic punch however, eventually cresting with a clattering railroad beat resolving itself slowly out of the misty depths, which somehow sounds like Burial programming the rhythms of Tony Allen on Fela Kuti’s ‘Gentleman’. This is genuinely great stuff, if entirely unlikely to win over any of his amassed critics.

And how can one usefully compare this electronic music to a festival closing set from GAS, with all of its connections to the woods? In what turns out to be an enrapturing set at the Teatr Im. Juliusza Słowackiego, Wolfgang Voigt leads us away from his more recent, new age-leaning Narkopop and back into the darker, more primal recesses of Konigsfort. This album is to minimal techno what Autobahn is to elektronische musik – both achingly nostalgic and futuristic; both deadly serious about the history of German culture while being playful, wry and self-aware. If the music itself (something Voigt described as an attempt to "bring the forest to the disco") precipitates an act of interior cartography, the film aspect to the GAS show thrusts the listener even further inwards. Treated, colour-tinted stills of foliage and slowly panning film clips of woods, kaleidoscopic patterns of branches and roots, forest scenes graphing off into blotter sheet rectangles and squares eventually slough off all intrinsic sense of themselves and it feels as though I am travelling through an electron microscope view landscape of my own synapses. This masterful ambient techno is heavy when played live of course but Voigt doesn’t associate the forest with anything obviously negative, he is too much in love with his own hippyish, pastoral youth and the strong totemic pull of the German countryside. Any unease that comes from his music – the diegetic-like clash of one track slowly fading into the next, the relentlessly pulsing sub bass, the ominous weight of German classical music – evaporates with prolonged exposure. He is like a father saying to a child: “Give it time… your eyes will adjust to the dark.” But despite the undoubtedly psychedelic properties of this show, how in turn can we connect this to Rabih Beaini’s punchy and head-mangling live soundtrack dub to Vincent Moon’s Híbridos? This is a much more literal look at the psychedelic potential the (Brazilian rain) forest offers to people who come from all kinds of different geographic and social backgrounds (including the more rootless, EasyJet-borne, casually spiritually questing Western backpacker as well as South Americans of all stripes. His position is fair but the viewer’s ability to enjoy Moon’s work is still mainly contingent on how they feel about this aspect of what he does).

Zimpel/Ziołek photograph by Theresa Baumgartner

Perhaps the best music of the entire eight day festival is the debut performance of Wacław Zimpel and Kuba Ziołek’s self-titled debut album, which sees the virtuoso guitarist and clarinet player join in pointilist harmony, creating, via a sublime blend of minimalism, folk and avant pop, a pantheistic sense of wonder at the order of nature and its perfect fractal depths. A view which will only hold tight when one doesn’t have dirt or blood under one’s finger nails. But the sheer romantic beauty of looking at a wooded glade in the same way you would look at a star constellation or imagine the inner workings of an atom is no less profound for it not containing the ugliness and imperfections of quotidian life. Well, certainly not in this case anyway. The violence of nature is not ignored but rather subsumed into the poetic whole: "Wrens have been gorging on/ Meadows blindly/ Following the bride… Under aspen tree/ We will vibrate/ Wiping out the birds."

(Let me break thematic stride here for a second to say that most of the truly outstanding music of the festival is home grown. The noise rock duo BNNT are, of course, capably augmented by Swedish mensch Mats Gustafsson, on sax and electronics but they would have been incredible on their own. The sight of two topless twitching noise rock Poles, wearing executioner masks, one behind a drum kit, the other playing what appears to be an actual anti-tank missile kitted out with pickups and bass strings is enough to create quite a stir on its own but their exploration of subtly modulating rhythms and riffs that call to mind Shellac at their most minimal and My Disco at their most hypnotic are astounding. Siksa’s uncompromising, visceral and quite literal, attack on misogyny clears some of the venue and one doesn’t need to understand Polish to get the point. Men! The pain you feel on watching Siksa is merely the patriarchy leaving your body! SUBMIT! In the unlisted Secret Lodge basement bar of the Forum hotel, two thirds of the hypno rock trio, Lotto – drums and guitar – tackle Albert Ayler in blazing free rock/no wave style, dealing out lacerating grooves somewhere between PiL, Massacre and Fushitsusha. There is a rumour that this duo will be recording for Instant Classic next year. Polish/Angolan duo Lua Preta make more literal use of kuduru and carnival rhythms than anything you’d expect to hear coming out of Lisbon at the moment, while DJ 1988’s industrial dub ruminations are one of the most exciting elements on the Forum main stage.)

Siksa photograph by Michal Rasmus

But if one were to investigate the genii loci of ancient forests – if Unsound’s music bill alone is anything to go by – one would find that they were in rabid disagreement… perhaps they could be described as schizophrenic even. Spirits of the place, cease your damned cacophony! But it is the spirit of the place, in more modern Western sense of the term, that makes its presence felt on the discussion bill of the festival.

“In Poland there is more a sense of wilderness here. There is a primeval forest here. You still have wolves. There is more of what is natural in the landscape, whereas in the UK we have a very meagre subset of what should actually be there and so often when we go into natural places they are empty. My wife is Canadian and we went in quite a few forest in Canada and they’re such vast spaces. What is interesting is they are not afraid of humanity whereas in England if you went into a wood the birds would fly off, the foxes would make their exit and the badgers would bury themselves into their dens. In Canada [the animals] come up to you and check you out and often they can kill you as well, so there’s a very different dynamic going on. We were camping in a forest and we couldn’t sleep because it was so loud with the vibrancy of life, with the sounds of insects, the sounds of birds, the sounds of owls, the sounds of wolves and coyotes and it actually made me very sad when I came back to England and went into our so-called forests because we don’t have anything like that. It actually made me profoundly upset that what I’d taken for granted for my whole life as being wild is actually very far from that.”

Not my words of course but those of landscape artist and folk/drone musician Richard Skelton. The stark truth of the matter is that the talks on forests at Unsound (while often being thought provoking, hilarious or psychedelic) are for the most part the most horrifying and nerve jangling aspect of the bill. Convincing good news is hard to drum up when talking about the fate of our natural wooded areas but a suggestion for a potential solution does come from an unexpected source. Mat Dryhurst embarks on an hour long talk about the blockchain – an online ledger that essentially facilitates secure online transactions and interactions because of its decentralisation, first suggested in the early 90s but now rising to prominence due to Bitcoin. His mind appears like a smooth, flat pebble skimmed expertly across a pond as he skips from one fascinating-sounding aspect of his topic to the next, while pretty much any of them could have taken up the full hour. One of these ‘skips’ is a tantalising but all too brief look at Terra0, what he refers to as "one of the more psychedelic [blockchain] projects in a creative or artistic sense". The company is run by folk in Berlin and driven by new concepts of ownership and maintenance working toward automated resilient and sustainable forestry. The idea is to use the blockchain to allow for the forest to negotiate on its own behalf. He says: “Load up a forest with a load of sensors so that it can understand the levels of oxygen in the air and the number of trees in the forest. Give the forest access to market information like the price of wood. And allow the forest to slowly sell its wares but in its own interests. It sounds like science fiction but it’s also a pretty compelling argument. It’s going to be very difficult to do but their vision of the future is going to be one in which forests are – on a protocol level – going to be looking out for themselves against nefarious human interest."

Richard Skelton photograph by Michal Rasmus

It’s imperative that like Mat Dryhurst we try and imagine positive futures for the environment and how they might be realised in a constructive manner but Skelton’s warning hangs in the air as I head into a talk on the Białowieża forest – Europe’s last remaining primeval woodland which is under threat of destruction. Sylwia Iwanowska an ecologist who has lived in the forest for five years is funny and world weary as she talks about the difference between how rich and vibrant this ecosystem looks on Wikipedia and in officials booklets and the reality on the ground. As huge as it is, this 3,000km2 is all that remains of the ancient forest that once covered all of the European plain, prior to the agricultural revolution. Part of the woodland is completely protected as it is a national park in Belarus but on the Polish side, it is under the jurisdiction of three different forestry commissions and in spite of this (or because of it) 84% of it is threatened by logging.

The forest has plenty of oak trees that are so old they have had names for generations and are well into their fifth centuries alive. Great Mamamuszi. The King of Nieznanowo. Emperor of the South. Emperor of the North. Southern Cross. The Guardian of Zwierzyniec. Barrel Oak. Dominator Oak. The Jagiełło Oak. Tsar Oak. Patriarch Oak. I mean, seriously, what kind of person would dare raise an axe to a 450-year-old tree called the Dominator? And which of these trees will see its half-millennium birthday?

Diminished as it is, Iwanowska describes the breathtaking biodiversity of the region and goes on to say that it is reflected in the way that humans have traditionally lived there. Villages have existed in the forest for millennia. There are records of hyper-localised religious and folk music traditions going back hundreds of years which differ starkly from one village to the next. The panel is filled out by the artists Peter Cusack, Martyna Poznanska and Karolina Grzywnowicz talking about art installations referring to forests they have designed for Unsound but really the stars of the show (for once) are the people waiting to ask questions at the end. An impassioned quartet of (young, cool, female) ecological protestors reject asking questions in favour of making powerful (and emotional) statements. The four protestors – or Puszcza Riot as they should obviously call themselves – have come directly from a blockade fighting the loggers to speak this afternoon.

A woman with spiky hair and T-shirt stencilled with a chainsaw logo says: "We are four people who have spent time at the protest camp over the summer. The activists need financial support because it is a very urgent situation. The logging is now being done by harvesting machines… it is important for you all to know that each machine can cut down up to 300 trees per day, and there are five machines currently operating in the forest. The activists are trying to block these machines every day… it is happening right now! What do we want? We want the Polish side of the forest to be completely protected like the Belarus side."

Her compadre with dreadlocks takes the mic: “They are logging in the third zone of UNESCO! You are only allowed by law to log in the fourth zone but they break the law all the time! They are logging in the third zone – taking down trees that are over 100 years old! This is against the law! And they are destroying the habitats of endangered species! I am so emotional because this is so urgent!”

They receive a standing ovation and as the talk comes to an end activists, artists and festival people hang around together afterwards to swap contact details and talk about what can be done next. Their presence caused a very tangible rupture in proceedings but also acted as a reminder that we don’t need to privilege activism over art (or vice versa) and that no one’s forcing us to make a binary choice between them.

Photograph of festival directors Mat Schultz and Gosia Plysa by Michal Rasmus

“We shouldn’t just see forests as places of escape but work out how should we re-evaluate our relationship to them and in doing so re-evaluate our relationship to nature. Rather than the naive idea of a post-urban world that William Morris suggested in his, actually very irritating book, News From Nowhere, I wondered if perhaps we could see forests as places of resistance against dominant political forces and corporatism and conformity."

Not my words of course but those of well-dressed arboreal flaneur, learn’d friend and co-editor of this very fine site, Luke Turner esquire. His talk is called Uprooting Babylon: The Forest As Counterblast To The Hollow City, or, as he also calls it, Chopping And Fucking. It is spellbinding, powerful and funny. (Well, I would say that wouldn’t I? But that doesn’t make me wrong.) The agreeable way in which Turner talks (as if he is always just about to offer Derek Nimmo a slice of Battenberg and a schooner of vintage sherry) allows him to present some of the apocalyptic, unsettling and scathing things he has to say as chummy digressions rather than spittle-flecked admonishments or wide-eyed horror-filled ravings. He starts with the etymological roots of the word for forest (originating from the Latin for outside) before leading us on a journey that involves porn shoots, gay cruising, several members of Throbbing Gristle, the duality of the forest as regards mental health, the untweeness of nature, arboreal hallucinations and how Epping Forest has intersected with his own family’s history in several surprising ways over the decades. But I’m not going to go on too much about this here, if you want to know more you’ll have to read his book, Out Of The Woods when it comes out in 2019.

In a bravura finale he announces that he will officially change the name of his book to Chopping And Fucking if more than 100 people tweet him @LukeTurnerEsq asking him to do so. He drops the mic and then cartwheels out of the room to astonished gasps*.

A staple theme of dystopian science fiction is the shattering realisation that escape from modern industrialised civilisation is a phantasm and that the only genuine escape possible is that into daydream, fantasy or madness. Of course, as not-at-all phantasmagorical metal creatures roam the last scrappy bits of primeval forest in Europe, chewing up and spitting out hundreds of trees per day, soon the daydream and fantasy part of that dour equation will disappear with the last of the forest itself, leaving no alternative but insanity. This is the duality of the forest. The very real sense of horror that exudes from these ancient zones is the all too real threat of its inevitable and imminent absence.

So I’ll leave you with some words (not mine of course, but those of Werner Herzog), a recording of which echoed round my head long after the end of Turner’s presentation, in which they featured.

“I see [the forest] as being full of obscenity. Nature here is vile and base. I wouldn’t see anything [erotic] here. I would see fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and growing and then just rotting away. Of course there is a lot of misery but it is the same misery that is all around us. The trees here are in misery. The birds are in misery. I don’t think they sing. They just screech in pain. Taking a close look at what’s around us there is a kind of harmony. It is the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder. But when I say this, I say this full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it, I love it. I love it very much but I love it against my better judgement.”

(*I made this last bit up.)