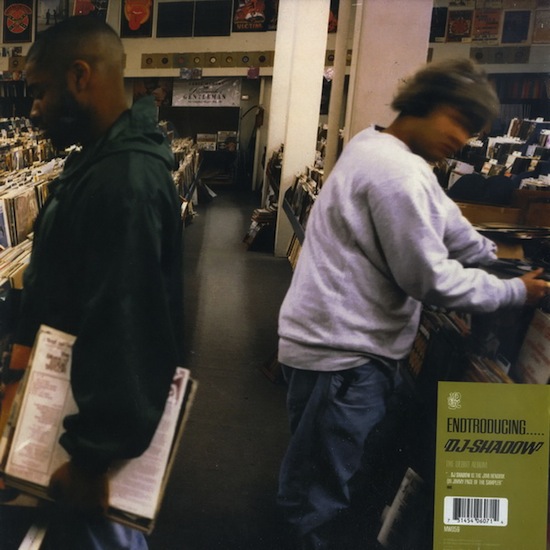

This feature was originally published in 2016 to mark Endtroducing’s 20th anniversary

It sometimes gets lonely if you’re a DJ Shadow fan whose favourite album by him isn’t Endtroducing, but there are a few of us dotted around the place. Indeed, at various points over the years, there’s been the sense that Josh Davis himself may not have been totally happy with the continued focus on his debut album. The 20th anniversary of its release (marked by a new box-set edition containing previously-released outtakes and a new selection of specially commissioned remixes) comes relatively hot on the heels of The Mountain Will Fall, Shadow’s fifth full-length studio LP under his own name (the sixth if you include U.N.K.L.E.’s Psyence Fiction, which Shadow very much does).

Many reviews for …Mountain… hailed it as a "return to form" and compared it favourably with Endtroducing, despite the two records having very little in common bar the name on the cover. Twenty years is a long time, and you’d expect an artist to develop, grow, and change: yet few of us seem willing to allow Shadow to move too far beyond the sound, style and overall creative vision of that first masterpiece. The sense of the first album being as much something he’s haunted by as something he can be proud of has been a presence – sometimes faint and almost intangible, at others a demon he feels compelled to wrestle with – in the conversations he and I have had down the years.

The first time I met Shadow was shortly after Endtroducing‘s release. Since then, as well as interviews for a number of magazine and newspaper articles, we spoke at length for a promotional biography sent to the media with advance copies of his third album, 2006’s The Outsider – a record that probably stands as his least well-received, no doubt in large part because of how deliberately he seemed to be trying to prove to the world that his own unique take on hip hop was as much about the beats and rhymes he loves as the emotive sample-sculptures he made his name with. Two years later we talked collecting, scratching, and how to write a narrative for a DJ set ahead of the release of a live CD and DVD of his and Cut Chemist’s third long-form all-45 tour de force, The Hard Sell; and in 2011 we discussed his ambivalence about the demands on a musician in a digitally mediated world, as his typically single-minded set-up for The Less You Know, The Better found him planting unmarked and hen’s-teeth-rare 12" promo singles in charity shops, a true-to-his-roots inversion of a traditional marketing campaign. Yet each encounter, to one degree or another, was conducted in Endtroducing‘s long (pun most definitely intended) shadow.

I spoke to Shadow recently to find out what he feels about his debut LP now, in the midst of both a world tour occasioned by the release of his new album, and the promotional duties around the 20th anniversary box set.

Your new record’s not long been out, and here you are, caught up again in the cyclical regularity of having to go back and talk once more about your debut. I know you’ve spoken on many occasions about how you feel the honour and responsibility that comes with having made a record that connected with so many different people and that they feel so invested in, and that’s special and important and you’re proud of that – and rightly so. But has there ever come a point where the milestone becomes a millstone, somewhat – where you have to kind of fight your way past it to get on with being who you are today?

DJ Shadow: I feel less and less like that every year, and I guess maybe even more so with every new record that I put out. I think it would’ve been harder to go through the motions of the 20th anniversary of Endtroducing if I hadn’t have released a new record this year. I find it easier: it’s almost like two sides of the brain, two sides of a coin – whatever analogy you want to use. I feel like, in a way, maybe I’m less threatened by it, because I know I was able to make an impact with a new record this year.

I just think, as the years go by, it’s harder and harder to really find a reason to be annoyed that you made something that people want to continuously talk about. Certainly there are contexts in which the record can be discussed which will get me on the defensive and make me want to put some kind of calibration or some kind of context on what the record means in relation to my career as a whole – because if people only know that record they might not know about Quannum, they might not know about Brainfreeze, they might not know about UNKLE, they might not know about ‘Nobody Speak’, or this, or that, or any of the other things that I busy myself with. So, on one hand, to those people I try to remind them that, sure, it was an album that represents a time and a place, but I’ve kind of learned a lot since then – not only on a production level but a songwriting level, an arrangement level; and I try to gently nudge them in the direction of checking out some other stuff I’ve done in the last 20 years! But that’s about it, honestly.

I still felt threatened at various times that Endtroducing would sort of envelop everything. But I never felt it in the ’90s, because I was working on the UNKLE record, which was a pretty big record, and The Private Press. All this stuff didn’t really start until around 2004 or 5. I think when The Outsider became an easy record for people who liked Endtroducing to criticise: that’s when it really flared up to a full fire. Since then it’s flared up here and there – but I feel like, with every new record that I put out, with every new thing that I do, whether it’s the Renegades Of Rhythm tour or what have you, it just becomes a little less hot of a fire, in my mind. I guess that’s always gonna be the case for some people, but in the mean time I’m still having fun and finding new ways to express myself, which is all that really matters to me.

And I’ve said this a lot lately, too: if, 20 or 30 years down the road, when everything’s said and done, I was never able to achieve that level of zeitgeist again, then so be it. I know how rare it is for anybody to do that. But I also feel like, OK, we’re getting on to 25 years of putting out records: that’s also kind of rare air for anybody who makes music. And I think you just end up kind of grateful for every opportunity that comes along.

We could be having the same conversation if you were Mick Jagger or Keith Richards and I was asking you about ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’ and people still wanting to hear you play that 50 years later. You get the sense that they’ve reached a point, an accommodation, an understanding: they’ve got a kind of pact with their audience that that’s what it’s going to be, and they’ll find a way of making it different. But the very nature of the way you’ve worked and the kind of music you set about making – while I realise there’s a live dimension and that gives you some flexibility, there’s the record-collector side of you and the focus on the object – this thing of you being someone who’s always been very true to the spirit of the artefact, and of the original artwork, and the provenance – so in a sense these questions are perhaps more complicated for someone making music in the way that you do than they would be for someone making music in what might be termed a more conventional band kind of structure.

DS: When I’m representing my music live I think of it very much in a rock band sense. When I first started doing festivals in the 90s there really weren’t other DJs playing the stages I was playing. So I felt I was being afforded an opportunity to kind of make a statement about what DJ music can be live. In the 90s, if you were a DJ you were in the dance tent, and you were playing house music and techno music. There was no such thing as a DJ – a solo DJ – on a stage, after a rock band and before another rock band: that just didn’t happen. So back then I studied the way rock bands – especially established bands – would, as you kind of said, strike a pact with their audience and say, in essence, ‘We all know what songs you wanna hear: you know what you wanna hear, and we know what you wanna hear. And we’re gonna give you those songs, but in between now and then we’re gonna play some music that you might enjoy discovering, that’s newer.’ And I think a band – even a band that’s been around as long as the Rolling Stones – I think that’s still the formula. You know you’re gonna get those songs, and you don’t mind sitting through the ones that you maybe don’t know very well because you know they’re not gonna let you down – they’re not gonna mess with you. And I kind of feel the same way about the way I structure my shows.

As far as the mechanics of how the music was made, there’s no denying: Endtroducing was extremely simple. That’s not to denigrate it – that doesn’t mean I’m knocking it or I’m saying my new stuff is better, or anything like that: it just means, I literally had, what, 12.5 seconds of stereo sampling at my disposal, and some turntable overdubs… The nature of the beast back then was probably about 50% looping and 50% chopping, and that was what you could do with samples. Now – heheh – the things you can do to sound! You can stretch them and manipulate them, and chain 12 plug-ins within a couple of minutes and have this incredible result. That stuff just wasn’t possible then. So, while I’m proud of the record, I can acknowledge, I think truthfully, that it’s quite simple when compared to my other stuff.

So that means that, when I play that music live nowadays, there’s a lot of things I feel I’d like to do – even things I don’t think the audience is aware of, like layering subs underneath the kicks, and layering crisp hats underneath the muddy, trashy hats of the ’90s. If I tried to play the music as it was next to my contemporary music, it just sounds like you’re closing up half of the sonic spectrum.

And, yeah, it’s about respecting what I think people like about the original music. I’m not gonna ever take it to the extent that I’m kinda George Lucas-ing moments of the album over and over again, trying to get them right over the next 30 years – I don’t wanna do anything like that. But, yeah – it’s a… fascinating conundrum through the years.

It sounds like, as well, within that process, that you’re learning things from this record still.

DS: I almost feel like there’s some kind of connection that I’m having trouble putting in to words, in the same sense that I’m learning things from my children still. My children are gonna be turning 12 – I have twin girls – and I think I’m starting to understand, as a parent, that when they’re 40 I’ll still be learning things from them, and about how being a parent is, when you’re in this decade and then that decade and then the next. And I think, just like any relationship, if I choose to become twisted and bitter it can be a source of distress or discomfort. But I think I’ve come to terms with the fact that I would prefer to see it as a gift. And I would prefer to see it as something that empowers me rather than something that diminishes me in some way.

You’ve got to do that, haven’t you? You’d probably go slightly mad if you tried to react to it in any other way.

DS: Yeah, totally. And, I have to say, I’ve done about 50 shows so far of the new tour that I’m on, and it is gratifying to hear people go berserk for ‘Nobody Speak’ and, even the show that I did last night, there was a very definite awareness of a pretty obscure song that I did under an alias a couple of years ago, as Nite School Klik, and I could definitely tell that the kind of early 20s component of the audience, that was their shit. Heheheh. So it’s nice, you know. Obviously the biggest cheers were reserved for things like the ‘Building Steam…’ drop and stuff like that – but… I don’t know. It’s satisfying to put out new music. And I think that’s the context in which I’m comfortable revisiting things from the past. I probably wouldn’t have agreed to do it at all – meaning the box set – if I didn’t know I was going to be putting out a new album, and if I wasn’t quite confident in the strength of the album relative to where I’m at musically right now.

And is that why… the idea of the disc of remixes: is that part of keeping it an evolving, forward-looking kind of a thing, not purely a retrospective exercise?

DS: Yeah. I’m comfortable putting that context on things at the moment. When Island had reached out about doing it, catalogue is something majors do quite well, and… I always feel I need a little bit of convincing. It’s not exactly an exciting phone call for me. The prospects of digging through my ADAT tapes once again… And I told them, straight up, that there’s nothing on the cutting-room floor that wasn’t excavated back in 2004, 5 when we did this thing called, I guess, a deluxe edition of Endtroducing. That’s where I really went all-in on seeing what was sitting on the DATs and ADATs and all of that.

But what I did do this time, which again is just another step in the process: for the first time I transferred all the ADAT tapes. I should be clear: on the 2005 thing I was going through finished mix DAT tapes, or session tapes; what I did this time was actually something I did about six, seven years ago – my erstwhile engineer, somebody I use a lot, said ‘I’m removing ADATs from my rig. If you have anything sitting around that you want to transfer into ProTools, you should do it now.’ And so, in a moment of rare foresight, I spent the two weeks, or whatever it took, to bounce all these tapes into ProTools.

While the nature of Endtroducing means there’s no true stems, because stuff was really cobbled together in the most shoestring way on a lot of ProTools sessions I no longer have, et cetera, what I do have, in most cases, is most of the assets. So I gathered together what I could, and so when Island called I was like, ‘There’s no cutting-room stuff, there’s the original album, there’s the disc of extras which I prepared 10 years ago, but what I do have this time around is stems.’ Or, I should say, repurposed stems, in most cases.

I talked about everything from just uploading them on the internet and letting people go nuts, and of course Island was like, ‘Well…’ Heheheh. ‘Let’s table that discussion for the moment.’ And I said, ‘Well, what I can do is I can A&R – like, really A&R – a really solid remix album.’ And I did, you know? All 12 selections on the remix album – those were personal. I reached out personally to all of them, and Island just let me get on with it. That was sort of fun to do, and I’m not gonna lie: it also gave me a lot of great weapons for my live show!

What have you made of things like the live-band version of Endtroducing that’s been touring? Have you ever seen that?

DS: No, I’ve never seen it. And… um… How can I put it? … I think I would be much more enthusiastic about a band that covered more than just one particular album of mine. I don’t ever really intend to record or to do shows with a live band. I don’t really have a problem with it, but it doesn’t really affect me either way.

Surely the facts that a) they are doing it, and b) people want to see them doing it, says something about your work, doesn’t it?

DS: Yeah, totally. I understand that there’s an element of… that it’s a compliment, definitely. But at the same time I just feel I have a natural fear of anything that feels like celebrating my own past to an extent that doesn’t allow me to continue to look forward. I don’t know psychologically why it is, but I get a little uncomfortable with nostalgia. Which is ironic considering the fact that I’m a record collector and all of that. But through it all, the words of John Peel echo strongly within me: you have support the music that’s being made now. You have to continue to look forward and learn from what’s happening. That’s my philosophy, anyway.

I feel like you’re being coy if you don’t do something and celebrate the 20th or 25th anniversary in some way. Just as I’ve never, ever had any kind of embargo on playing songs from Endtroducing, no matter how much I wanted people to like my new stuff – I’ve never, ever stopped playing Endtroducing, for that reason as well. It’s a give and take – it’s a balance. If there’s one theme, I guess, to this entire discussion, then it’s that.

The point about supporting the music is one I’d like to get into a little bit. I remember how, with The Outsider‘s first track [‘This Time (I’m Gonna Try It My Way)’, where Shadow sampled a vocal he had found on an unmarked acetate he bought during a sale of assets of a defunct radio station], you took elaborate steps to track down the vocalist, weren’t able to find them, and set up an escrow account so that royalties would accrue for whenever that person is eventually identified – and I think this is something that the record-collector fraternity as a whole is perhaps a little slow to recognise sometimes. Yes, there’s incredible interest and value in particular old records, which change hands for a lot of money and have holy-grail status and everybody wants them, often for very good reasons about how they sound and the way they make everybody feel – but ultimately the person who makes them doesn’t reap any benefit from that transaction at all, and that’s something that’s always struck me as a little bit odd: that some of the most obsessive fans of music end up spending the highest proportions of their disposable income on it, and none of that cash ends up in the pockets of the people who made the records. Whereas when you sample something, that equation does change in favour of the original artist when they can be identified. When you’re approaching something like a retrospective re-evaluation or a remix project of a record of yours that’s been around for a long time, and which is in itself made up of records that were around a long time before you came along – where does that go on that business level? And what about on that conceptual level – that idea of reappropriating elements of the past to make something new for the future. How does that all fit together with your general feeling of making sure that whatever you do honours the present as well as the past?

DS: I guess the easiest way to answer it is – it’s everything from zero to 100. The story I always recite – and have had to recite so many times over the years to different lawyers and different people within Universal – is that the business end of Mo’Wax was basically, like, ‘Give us the big ones [samples] first, and we’ll see how we get on.’ And I gave them the six or seven that were, to me, the ones that were the scariest, and the biggest use. It wasn’t about the big names, necessarily – although that played into it a bit, with people like Bjork and Metallica. But also things that were just sizeable uses, like the [60s psych] band Nirvana that was on Island. So I gave them those, and then that was… ‘Well, we’re out of time!’ And I was like, ‘…OK, I guess…’

At the time my thinking was, well, once they hit stores, you can’t take all those copies back. It’ll exist in the world. I just felt like I just wanted to get to release day. Sometimes there’s this balance: if you try to clear 10 things you’ll probably get lucky and be able to clear most of them, or all of them; try to clear 20 things, in my mind there’s gonna be at least one issue, maybe two – and then that’s when it starts getting into either re-recording stuff, or you’ve got to take that song off. So I just felt, at the time, a little bit relieved, because I was kinda counting the days: ‘Come on! Let’s get these records into people’s homes – nobody will ever be able to get them all back, and it’ll be an artefact out in the world.’

And then there were clearances that occurred pretty much on a yearly basis – pretty much the same, I would imagine, as records like Paul’s Boutique or any of that classic hip hop era between 88 and 92. I’m sure that there’s many albums that used a ton of samples where, pretty much on a yearly basis, there’s things being cleared. I actually just talked with Mike D about this recently, and he was like, ‘Yeah, I think we’re pretty much there now’ [with the 27-year-old Paul’s Boutique]. Heheheh.

So that process is ongoing. The hard part is that there isn’t a single person on the planet other than myself who has a better sense of all of the things that have come since that time. I’m literally the only person who has a kind of general sense of the timeline of who reached out, what the compensation was, whether they need to be consulted for synchs. There’s some people where it was cleared, it was all legit, everything’s cool, done deal – they just make their money off the mechanicals and that’s that. Then there’s other people that wanna be notified every time something’s going on. So it just varies, totally.

And I guess you have to manage that yourself, then – if you’re the only one who knows where everything sits. And when you get the call from Island saying, ‘We wanna do the 20th anniversary re-issue, how do you want to do it?’, you’re probably also mentally flipping through your index card system to think, ‘Of course, if we go down this route, I’ve got to contact this person to get their permission to do that with it,’ and blah, blah, blah.

DS: Well, there’s a lot of ins and outs that I probably shouldn’t discuss on the record. I am able to tell other people what they should do, to the best of my ability to do so. I never think it’s a great idea, usually, for someone like me to personally engage. I used to do more of that, with the people I sampled or whatever, but the wide range of responses you can get is, in some ways, shocking to the senses. I always like to remain a fan, put it that way: and I like to hold the idealised version of what these artists are like. Greed is one of those components of human nature that’s inherent in everyone, and sometimes it is an unpleasant thing to engage in.

What you’re saying is, you’ve had run-ins in the past with people you would consider among your musical heroes, who’ve effectively put the block on some project or other because of what one might consider unrealistic demands?

DS: Oh, yeah. That’s definitely safe to say. I think one of the things about ageing is the jagged peaks become a little bit mellower…? Heheh. And I feel like I’m able to understand a little bit better where that sort of tack comes from. You can have a million different experiences in the music business, especially in the 60s, 70s, 80s. And not all of ’em are gonna be pleasant, and it affects different people in different ways. Usually, to be honest, it’s not the artist – it’s usually people that have nothing to do with the creative process. It can be kin, it can be people who bought the catalogue for the express purpose of going right through whosampled.com and finding out what they can dig up. So, yeah – it’s all part of the wonderful strata.

I also wanted to touch on the critical reception Endtroducing got on its original release. As far as I remember it, quite a lot of coverage that the album generated was people who don’t really cover hip hop, or know very much about it, hailing you as a the saviour of hip hop because you were doing something that brought a hip hop sensibility and mode of working into their world. And it allowed them, in some cases, to be dismissive of music that they had no particular interest or understanding of, that you held very dear to your heart. I guess that must’ve set up a few conflicts inside you over the years, as that sort of line has become the one that history has tended to adopt.

DS: Yeah. It’s interesting. And I’ve always been aware of stuff like that. I’ve tried to tell people that the reason I don’t really get excited over good press is that I don’t want to get agitated over bad press. I don’t wanna get too high on good press, too low on bad press. It’s just not a healthy way to engage with my own feelings about my music.

Incidentally, the very, very first review that James Lavelle and I saw of Endtroducing was very negative! It was in The Wire, and the context of the review was that, you know, Mo’Wax was so far behind Ninja Tune. Heheheh. And people wonder why there was this sense of a feud between labels! We just kind of looked at each other and we were like, ‘Oh, well, let the floodgates open!’ But, not to be facile, that was literally the last bad review I ever saw for that album.

But at the same time, I’ve always known there was another side. And I kind of spent, I guess, the better part of a decade dealing with, if not a real backlash, then a perceived backlash, in my mind.

When Endtroducing came out there was a honeymoon in the press, and on one hand I knew it wouldn’t last, but on the other hand it was kind of sad when I saw that it was turning. Ego being another component of human nature, you wanna think, ‘Oh, I can keep this honeymoon going – I can make everything perfect, make everybody happy with everything that I do.’ And you quickly realise that that’s just simply not possible, and was never possible.

But speaking to what you were saying: magazines like The Source, even though that was how I broke through in the industry – in fanzines and hip hop magazines – by the time Endtroducing came out, hip hop had changed to the point where something like what I was doing really didn’t have any room alongside people like Mase and P Diddy, and everything that was going on with the east coast/west coast, Death Row, and all that stuff. What I was doing seemed like just another universe, I guess, for people engaged in that world. The most I could hope for was something like a review in Hip-Hop Connection, but it’s not like I was ever gonna be covered in any major way. But I’ve seen it happen with funk bands that are covered only in the rock press, and rock bands that cross over to being played on black radio. You just never know what your lane is gonna be.

Another one of my favourite sayings is, you can’t handpick your audience. I feel like I’m making music for people who think like me about music, and that takes a lot of different forms. I could never generalise – but I think if I were to generalise, I’d think that you would say that most of my fans are music lovers who are looking for something outside of the mainstream: maybe a little bit hard to pin down, a little bit hard to categorise. And I think that’s why I continue to kinda happily sail along on roughly the same plane for 20 years. Which I’m totally fine with, obviously.

Good! Well – I’m pleased to hear you’re happy to be doing it, and pleased you are still doing it.

DS: Thanks. Maybe if we were talking a year ago I’d be filled with fear and doubt and all the things that come before, when it’s been three or four years since your last record. But certainly, having the benefit of having a new record out, and being on the road, and kind of riding one of those waves of creativity, and being out there, as it were – it’s good for the mind! Heheh.