Before we begin, a bit of context.

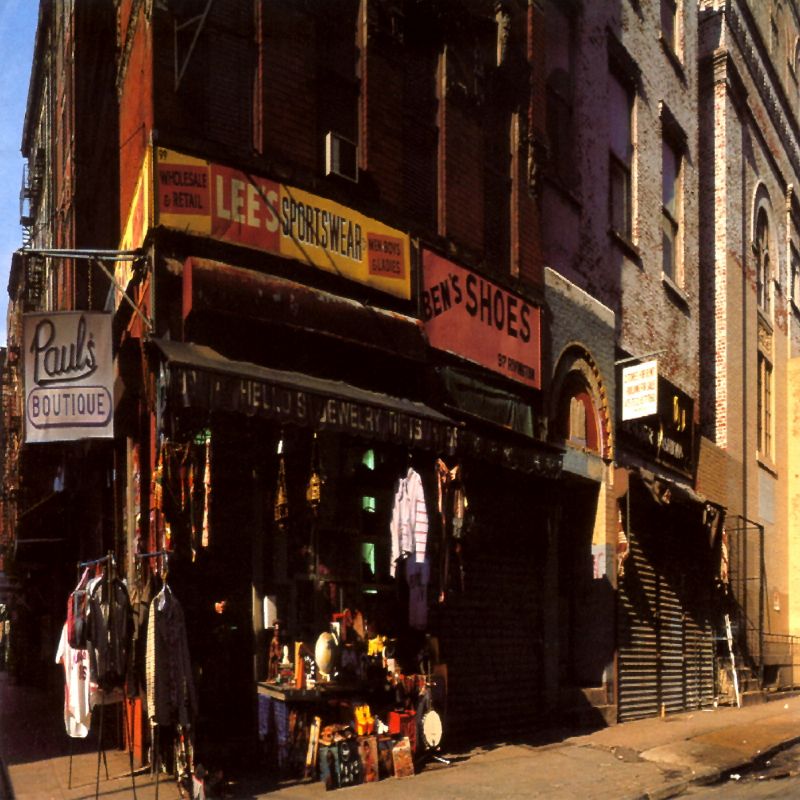

It’s hard for me to be objective about Paul’s Boutique because I firmly believe it to be one of the greatest albums ever made. And because it’s been around for thirty years, and I bought it on the day it came out and have lived with it and loved it for all that time, it’s pretty tough for me to take too many steps back from it and to try to see it in any kind of different light. Obviously, music that you care about and which attains and retains importance for you will morph and move about somewhat in your consciousness: it takes on new shapes and new meaning as life barrels along, and your personal perspectives change as knowledge and awareness deepen. I hear new things in it, even now, even after all those years and all the untold times I’ve put it on and pored over it, and the precise nature of what I hope is my understanding of it keeps on changing just as the responses I have to it and the interaction I enjoy with it will differ depending on who I feel like I am and where I’m at in my life when I re-engage with it. But on the only levels that really matter – the deep-down, heartfelt gut reaction; the visceral thrill and excitement that it engenders in some part of me that I can’t locate, never mind explain – I’m a long way past being able to disentangle what I think from what I feel. This is just a great record. I can’t get past that.

So this isn’t going to be a piece that reappraises or reassesses the record. I’ve got nothing coherent to say that could do that job. It’s also – to take a step slightly to one side of the path taken through other pieces in this series – not going to be a look at how the record was made. That’s a fine story, but it’s been told thoroughly and very well before. I had a crack at it in 1998, in a book; didn’t really get very far with it but as a rough early sketch it was OK. Age, what I hope is a little bit more wisdom, and a bunch of illuminating interviews later, I gave it another go, in a piece published in NME (July 26 edition). Best of all, there’s Dan LeRoy‘s book on the album, part of the 33 1/3 series from Continuum, which tells the story with wit, insight, colour and deep research. Leroy and the excellent Peter Relic are publishing a new e-book, winningly titled For Whom The Cowbell Tolls, that adds a ton of new information and detail to Leroy’s first book, to coincide with this anniversary. At the time of writing it’s yet to be released, but two things are certain: first, coming from that provenance, it’s going to add considerably to what was already the definitive story; and second, if that’s the case, then there’s little to be gained by having me attempt a pale rehash here.

So what I’m going to do here is to mostly ignore the "what", the "how", the "where" and the "when". What I want to look at is the "why" of Paul’s Boutique. Because, certainly, at the time, that was probably the most frequently asked question – after the millions of Licensed to Ill fans had finished asking, "Dude, what is this shit?"

The fact that Paul’s Boutique wasn’t Licensed to Ill‘s direct successor was the first thing that everyone had to deal with. Plenty of people were somewhat underwhelmed by that – including, it now transpires, at least two of the team that produced the record. John King recently explained to me how he and his Dust Brother partner, Mike Simpson, were disappointed that the Beasties had made a deliberate and conscious decision not to repeat any of the formula that had made their first album a multi-million-selling global phenomenon, and became dismayed as the realisation dawned that the group had decided to avoid as many of the traditional promotional tactics as possible. As excited as they were about the new sound they were helping Adrock, MCA and Mike D fashion, they’d given the group a ton of their best musical ideas, and they needed the record to sell well: they were broke and they were on a percentage. Just one or two singles would have helped. The Beasties were having none of it. The nearest the record comes to retreading the Licensed… territory is ‘Looking Down The Barrel Of A Gun’, but that mash-up of MCA’s live bass and the Incredible Bongo Band does more to predict the live-band wig-outs of Check Your Head than it does to recall ‘No Sleep ‘Til Brooklyn’. It also resolutely and steadfastly remained unreleased as a single.

Their determination to hit "restart" was total. It’s the secondary audible driving force on the record, close behind the rampant, almost self-indulgent, sense of joy at the act of anything-goes musical and lyrical creation. Key lines are peppered throughout, but if you want two short blurts that encapsulate the purpose of Paul’s Boutique, I’d recommend Adrock’s invitation in ‘Hey Ladies’ – "I got an open mind – why don’t you all get inside?" – and his part of the one bona fide hook on the album, ‘Shadrach’s "If I had a penny for my thoughts I’d be a millionaire". This is a record that’s first and foremost about showing off, but it’s about showing off how many clever ideas you can pack into 45 minutes.

But that siege-mentality approach to anti-promotion and a full-on retreat from the conventional means by which music was marketed (the band didn’t even tour the record: Paul’s Boutique had been out almost three years before the Beasties played their first post-release gig) – where did it come from? There seem to be two main answers to the question. The first is found in their debut album, what it set out to do and what it actually achieved: and the second is rooted in the one single most basic fact about the Beastie Boys which always seems to get overlooked – that from at least that point in 1984 where they decided to have a serious crack at making hip hop records, they were rap fundamentalists, hip hop to the bone, as obsessed by making great and authentic music and advancing their own skills and the pushing the art form forward as any of their golden-age peers. And if you were around and involved in that period, you knew you were walking among artistic giants.

"We felt pressured while we were making Paul’s Boutique by that next wave of records that followed after the 87 stuff," Mike D told me in 1997. ‘BDP’s second album, the Jungle Brothers’ first – that was perhaps the last wave of truly exciting hip-hop, until the Wu." Too bloody right they were pressured: when your friends and contemporaries seem to be pushing out new music more or less every week that keeps on taking your metier to another, higher, place, you know the heat is on.

Art doesn’t get born in a vacuum, and hip hop in particular has always been an art form where the practitioners are acutely aware of the developments going on around them. The metaphor of rap as a contact sport is a reliable and accurate one: the friendly rivalry and intense competition between artists has always been a powerful fuel-source keeping the music moving inexorably forward. Chuck D made ‘Rebel Without a Pause’ because he thought Eric B & Rakim’s ‘I Know You Got Soul’ was the best record he’d heard in his life, and he wanted to try to compete with it, needed to at least try to top it. That’s how it worked in that era: and the Beasties, as a group who would later be able to accurately and reverentially claim were "from the family tree of old-school hip hop", simply could not have avoided trying to outflank their contemporaries. That’s the nature of the game.

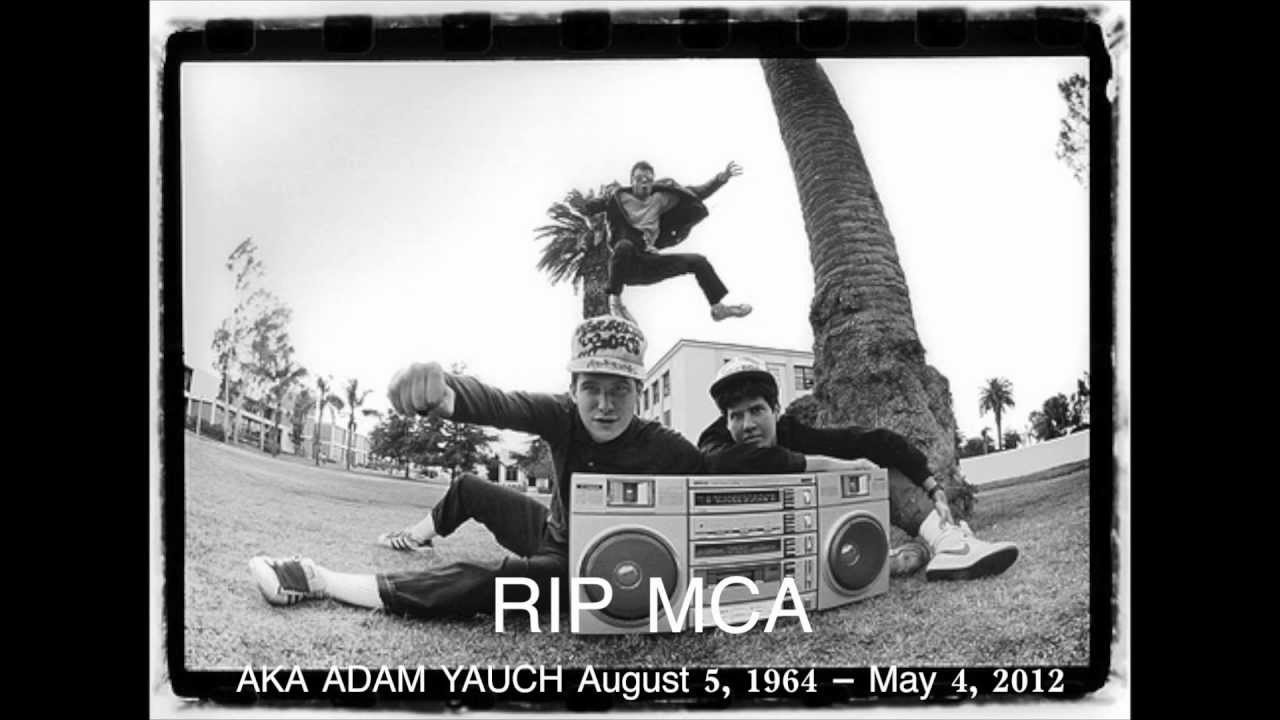

Yet the Beasties remain a group who have never really been accorded the respect that their work demands. Perhaps because they prefer (both in interviews and on record) to crack wise rather than to impart wisdom, perhaps because they’re white and Jewish and working in a black music form, Adrock, Mike D and MCA never get mentioned when people are talking about the all-time greats. But these are some of the finest rap technicians who’ve ever committed rhymes to tape. And on Paul’s Boutique they prove, time and again, that they’re masters of an outrageously broad variety of styles and flows. They riff on block-party-era call-and-response structures like a Budweiser-swigging Cold Crush Brothers; they dazzle with dextrous interplay that leaves one emcee finishing another’s rhymes, another’s thoughts. Go back to ‘Hey Ladies’ and give it a real hard study: this is incredible rapping. And they lace these performances with a depth of subtle wit that’s almost Shakespearean in its multifaceted complexity. In ‘The Sound Of Science’ the lyrics invent new elements ("Sheastadium, varadium") while the music tells its own story of the science of beatmaking, as the Dust Brothers collide several Beatles samples to make an expensive new compound. ‘High Plains Drifter’ features loads of references to westerns and Clint Eastwood films but doesn’t sample from any soundtracks, while the track that precedes it (‘Eggman’) mashes themes from Superfly, Psycho and Jaws together while the Beasties studiously refrain from rhyming about movies. We hadn’t heard the like of this record before, and we’ve not really ever heard anything quite like it since. You could argue they went too far – that their need to break the mould became a handicap and that the record is overburdened with ideas: but then you’d have to argue that this record is less than brilliant, which is very clearly not the case.

So we have an obvious and understandable artistic and creative impulse. They wanted – needed – to up the ante. They had to make something different from the first album, because hip hop doesn’t stand still; they had to make something that took account of what others were doing with the music and progressed the entire genre further into the future – that’s just the way it was in the golden age. So when the band first heard the Dust Brothers’ instrumentals round at Delicious Vinyl boss Matt Dike’s flat in Los Angeles, it’s easy to see why they were entranced by the possibilities.

Listen to ‘Shake Your Rump’, the album’s opening track, one of the first couple recorded, and still in many ways the most extreme example of the Paul’s Boutique methodology: this is music from another plane entirely, where ideas and sound-pictures collide, shatter and are reassembled into something new, all in an instant. It’s a sample collage, but it’s also a sculpture. There’s no way it should work with those three voices weaving in and around the different fragments of old records, lyrical visions jousting with musical innovations to the point where you feel like the whole thing could be about to collapse in on itself under the sheer weight of the different thoughts that it’s built out of. And yet it’s perfect. Try to work out why by unpicking it and the whole thing unravels: like that wooden bridge Sir Isaac Newton was said to have thrown over the Cam which had no bolts holding it together, until someone decided to take it apart to see how he’d done it and couldn’t work out how to rebuild it without conventional joints and fasteners. (That story is false, of course: but when the truth doesn’t suffice then myth rushes in to fill the gap – a feature of human storytelling that a certain band have proved themselves skilled at using over the years.)

But the other aspect of why the record is so different has nothing to do with hip hop or genres or artistic advancement, and a great deal to do with money, business and the messy realpolitik running three still young men’s lives. For the Beasties, Licensed To Ill had been at best a mixed blessing. They’d made an epochal classic, a record for the ages: but its runaway success meant they were very quickly unable to control it. For every fan who got the joke, there were a dozen who thought the nerd-rap shtick was for real; for every listener laughing with the trio as they satirised frat-boy jerks with laser-sharp raps, there were frat-boy jerks who thought irony was something their mom did to their prom-night tux, who were ready to proclaim the Beasties kings. Somewhere in the middle of that the group lost their way. Maybe, somewhere, they started to believe – perhaps not in the hype, but certainly in the hoopla.

The jerks they portrayed on the debut were certainly sketched from reality, but there was always more to them than that one limited slice of a persona. Here’s part of a conversation I had with the trio in 2004, just before the release of what was a pretty introspective and (by their standards) serious album, a love-letter to their home city made in the months following the September 11 attacks, called To The 5 Boroughs.

AB: Do you ever look back and get embarrassed by anything you’ve done on record, or said in interviews?

Adrock: You mean, for instance, like the song ‘Girls’, on Licensed to Ill?

AB: Well, yeah. And the way that the persona that you crafted at that time was taken at face value by so many people.

MCA: I’m sure there are some things that I’ll hear that’ll make me cringe a little bit.

Mike D: And you’ll have the three of us sitting here, and you’ll put on the Licensed to Ill home video. Yeah. I’d cringe, but at the same time, I’d look at it as, what we went through and what we did was absolutely necessary. Point A was necessary to get to Point B.

AB: People are used to seeing musicians grow and develop gradually. With someone like the Rolling Stones, you can see their step-by-step progressions, whereas you’ve made radical jumps between records. And I think that the reason people still focus on the differences is because the records have been so different, that the line that connects them isn’t always clear to someone who’s not in the band.

Adrock: Errrrr… true. It takes so long to make a record, there’s years in between. And things happen.

Among the things that happened between Licensed to Ill‘s release in 1986 and the first sessions for Paul’s Boutique two years later were the Beasties becoming global stars, and their vast new audience buying the records without getting a proper sense of the people who made them. This disconnect reached its apogee during the infamous Liverpool gig where the band were pelted with beer cans after a tabloid witch-hunt had stoked public fury, with Adrock later charged (and cleared) of injuring a female fan by swatting one of them back out into the crowd with a baseball bat. When something like that happens, you’re probably going to want to take time out to re-evaluate and reassess. But the other thing that happened was an almighty falling out with the Def Jam label that had been their home since 1984 and which, in the dual controlling persons of Russell Simmons and Rick Rubin, had become a kind of additional part of the band and their process. To make matters more complicated, the pair didn’t just own the label: Rubin had produced Licensed… and was the band’s first DJ; Simmons, who strenuously denies a conflict of interest, was their manager through his agency, Rush, titled after his nickname.

Whether they ever articulated it to themselves or to anyone else in these precise terms is not clear, but it appears likely that getting off Def Jam would have been the only way the Beasties could ever have managed to draw a line under the madness and give themselves a shot at meaning something more. Chances are that it got as basic as: if we ever want to be who we really are, we have to start again – whereas if we stay with Russ and Rick we’re going to be churning out identikit records for diminishing returns and we’ll be leaving our 30s, still dressed like dorks and spraying each other with beer on stage 100 nights a year. You can see why they needed to get out.

From that 2004 interview, again:

AB: What do you think would have happened to the band if you’d had to follow up Licensed… and not got off the deal with Def Jam?

MCA: You mean if we had failed with that lawsuit and the judge had sided with Def Jam and not let us move to Capitol? I dunno. I don’t know. I was definitely not too settled about working with Def Jam and the whole attitude over there. So I don’t know what would have happened.

Mike D: I can’t imagine.

Adrock: They would have wanted us to make ‘Fight for Your Right to Party Part 2’.

MCA: I dunno. Maybe we would have changed the name of the band and carried on making music.

Mike D: Yeah, I can’t imagine that we would have just caved in and made ‘Fight for Your Right Part 2’, ‘Paul Revere Part 2’, ‘Brass Monkey Part 2’, and go out on tour wearing VW medallions. I can’t really imagine we would have done that, which is what they would have wanted us to do. So, yeah, I guess that would probably have been it. I guess. But that’s all hearsay.

MCA: We could have called ourselves the Disco 3.

Mike D: That wasn’t taken at that point. But I don’t know how that works. Was the name declared available after a certain time period?

Adrock: We should recall that name.

MCA: Yeah, we’re now officially called that. It’s ours!

AB: You could have it as a reserve name. You could use it if the Beastie Boys name is injured, or having a run of bad form.

Mike D: Yeah. It’s a pretty fly reserve name.

MCA: Exactly. We can call upon it in any situation.

That all sounds like it’s true. That all sounds pretty real. But it’s only one side of the story. In 2008 I got another angle, when I spoke to Simmons.

Russell: Beastie Boys would never admit to this, but they were pieces o’ shit the minute they had a hit. No-one wanted to work, they all wanted to quit, they all hated each other. Very difficult.

AB: That relationship never…

Russell: I was down to keep suckin’ up to ’em, figurin’ out what to do, tryin’ to figure out how to manage ’em. But Rick… Rick’s an artist too. He was like, ‘Well, you fellas can go, give us our money, get away.’ Rick would tell that to Bob Dylan or anybody else. ‘Get the fuck away!’ ‘Cos Rick’s an artist too: ‘I’m gonna make your record, you’re gonna be challengin’, I’m gonna be challengin’; you’re gonna show up some times, I‘m gonna show up some times, and when we both show up, we’re gonna do our job. How’s that?’ Not, ‘You’re never gonna show up, or gonna show up half the time.’ Rick’s gonna show up half the time and you’re never gonna be here? That’s not right. But that’s how the Beastie Boys were. And Rick was not fully ready to do whatever it is that you do at a record company.

AB: Again, looking as a fan…

Russell: I wish I had sucked up to them forever. They’re so talented, such nice kids. They just had a tough time – you get a hit, you get a little crazy.

AB: Did you ever repair your friendship?

Russell: Yeah, I’m good wit’ them. Oh yeah, I repaired my friendship, always. I have loved them always.

AB: ‘Cos there was that time… [I was about to remind him of his threat in 1987 to release an album called Whitehouse, purported to contain Licensed to Ill outtakes; and the several mentions the band made to any journalist who happened to be within earshot to the effect that Simmons was withholding monies they’d legitimately earned. As late as 1994, and Ill Communication, the group were still using this episode as inspiration: at one point on the record they say they’ve "got fat bass lines like Russell Simmons steals money". But that day in London talking to Rush, there was no need. He knew where I was going. Five words into the question he started in on his answer.]

Russell: Yeah, but that was their job. They were completely retarded at the time. They were new artists, you know? Every artist goes through a period… or a star, where they somehow believe that the work that they did was theirs, that it wasn’t given to them as a gift, and that they give it back to everybody else, and it’s just a job: they believe it’s like… You know, they get disconnected. More than most people. And they become a little bit, you know, divas – men or women. And you have to live with that. Then hopefully they come back home. Sometimes they can live their whole life retarded! Or… it’s a bad word to use. My buddy Bobby would have a fit, right? Sometimes a comedian or artist or poet or rapper will live their whole life without having the humility that they could have, because they’ve been given such great talent.

AB: Again, as an outsider looking in on that period, I wonder whether part of the problems that you had with them, over money and things, were down to the fact that you were both the label and the manager at the same time, and that there was a conflict of interest there. Which must have happened to…

Russell: We never asked for nothin’ that we shouldn’ta got. I don’t think that there was a negotiation issue with money. I think it was a personality issue, in part with Rick, but they were very difficult. We made them overwork – we did too much pushing to them to work. They were in England and had problems, Adam got arrested I think and somethin’ happened, Molly Ringwald wanted him to come home: they all had personal issues. And with each other. And we were not sensitive enough, or talented enough, to manage our way through it. And so… I don’t know that another manager wouldn’ta had some o’ those same problems, but I do believe that, yeah, there’s a point that, you know, you have to be skilful when there’s a guy who’s strugglin’ and you wanna make him the most productive. You have to know what’s the most productive you can get. A guy needs to go to rest. Do they need a vacation from each other? What do they need? So I could say, we didn’t know how to do it. I was willin’ to keep tryin’, though.

Is there a bit of "fuck you" in Paul’s Boutique? Is there some sense in which the record went to such great lengths to raise hip hop’s creative bar, that it was so consciously above and beyond Licensed… in its sound and its style and its approach to the craft of music-making that you can see it as a giant middle-finger being flipped in the direction of Rubin and Rush? Maybe that’s in there. But more important – and more clearly discernable – is the undeniable need the band had to put clear blue water between themselves and their past. Bono once famously described a new U2 album as "the sound of four men chopping down The Joshua Tree", acknowledging that a milestone can be a millstone and sometimes a band needs to think it all up again from scratch. Paul’s Boutique is the sound of the "three jerks" the Village Voice had hailed for their debut taking chainsaws, machetes, Stanley knives and scalpels to Licensed To Ill and all it had come to stand for. That, you sense, is the real "why".

That the world wasn’t ready to listen has become just one more part of the story of a unique and fascinating career. You can’t see Paul’s Boutique clearly now because you know that, three years later, Check Your Head followed, turning the Beasties into the coolest band in the world, the group all other groups wanted to be, and as you look back at the past you see Paul’s…as a necessary step on a then-unfinished journey, a crucial stage in the development that allowed that to become this. At the time, though, none of that was in the stars: none of it had even entered its makers’ heads.

The plan to allow the record to find its own audience, the understandable desire of three young men badly burned by early infamy to not play the music biz game, can be seen to have worked too well. The record was a flop. To think that the band weren’t bothered by this is a mistake. The validation they would have received had the record been not just acclaimed by the rock press but devoured by hip-hop heads would have changed their story irrevocably. That it didn’t pan out like that caused them some consternation, not least because their record, which they’d been working on for well over a year, was beaten to the record-shop shelves by another album by a rap trio working with a gifted producer who’d taken a similar anything-goes approach to sampling: and, crucially, De La Soul were happy to do press, release singles, and tour.

"Paul’s Boutique was incredible," 3 Feet High & Rising producer Prince Paul told me in 2003. "Q-Tip was the first person I heard talking about it, then I immediately went and bought it. No: I bought it way before I heard Q-Tip talk about it! Right after I bought it, I remember me him and Pos talking about how great it was. It wasn’t ’til later, ’til I met the Beasties, they was like, ‘Man, we was mad with you when you made 3 Feet High & Rising! That’s what we were doing! That was our concept! We were putting all these samples together and stuff! And we were like, "Awww, now we’ve got to go back to the drawing board!"’ I was like, ‘Really?’ They were like, ‘Man, we hated you guys!’ Wow! It was funny, because I used Licensed to Ill as a basis for a lot of the stuff! I was heavily listening to Licensed to Ill [during the making of 3 Feet High…] That was my favourite! I thought Rick Rubin was a genius. Oh my God, I loved that record! That had a lot to do with 3 Feet High & Rising – just the fun behind it, and even at the end, on Let’s Get Ill, where they’re cutting in Mister Ed, and there’s all that awkward stuff. I’m like, ‘God! This is incredible!’ And so I said, ‘Man, I based a lot of my stuff on y’all!’ Isn’t that weird?"

So when I was speaking to the Beasties the following year, I told them what Paul had said, and asked if his recollection was accurate.

Mike D: I was telling the story earlier, but… Actually, I don’t remember running into Paul.

Adrock: I feel like I do. I think that was me.

Mike D: So there you go. But I was just telling the story earlier that I remember the day that I got 3 Feet High & Rising. I don’t know if it was the day it came out, or whatever, but we got it and we were in the studio, or on the way to the studio or whatever, and I remember listening to it, and I felt pretty crushed. I felt, ‘Oh fuck! We’ve been putting all this work in, and like, they did it!’ You know what I mean?

MCA: I think they’re pretty different, actually.

Mike D: I think in hindsight, they’re radically different albums in terms of tone and feel and even just in terms of what they do. But it was just…

MCA: Most rap records in the immediate time before that was just beats, and people yelling over the beats. All the beats people were trying to find were really big.

Mike D: And shit trying to sound hard: instead of being brain-expanding material, they were trying to be hard. And all of a sudden De La Soul came out with, like, musically and lyrically a whole expansion of ideas. And Paul’s Boutique did too. But whatever.

MCA: Rakim was the one that changed the game, though.

Mike D: He was still hard, though.

MCA: The beats were definitely weird. It wasn’t just looping up something.

Adrock: Public Enemy too.

Mike: Yeah, the Bomb Squad too. That was at the same time. There was an eclecticism to what they did but it was somehow more focussed, or more purposefully kept to a certain tone, whereas 3 Feet High & Rising had such crazy, different shit on it, going on at the same time.

Adrock: 3 Feet High & Rising also sounded like those tapes you made when you were a little kid, on your tape deck, when you tape all stuff. All those skits and things. I’m not saying it’s a child’s thing, though.

Mike D: You’re calling Paul a child?

Adrock: No.

Mike D: But the shit still sounds really good today.

AB: So does Paul’s Boutique.

Mike D: Well, I couldn’t judge on that. It’s not like I’m gonna listen to it.

He should, occasionally – maybe these days he does. And so should you. It always was, and will always remain, an absolute treat.