Who invented industrial music?

Okay, fine, I’ll wait until the laughter is over. Or the fighting. Or squabbling, really, whatever you want to call it. There are, shall we say, claims to the matter, a multitude of possible sources and sonic suggestions. There’s also the sense that you have to define what industrial music even is to begin with, and that will make the previous discussion seem like a tiff at a fancy tea party. Papers will be waved in the air, manifestos delivered with only the most loving of intents at the top of various rhetorical voices, and at some point someone will say something like "What even is music?" and the ontological crisis begins anew or worsens.

But let’s reframe this initial question or rephrase it: who invented industrial pop? For my money, it’s down to three guys from Basildon, two from London and one from Warrington, figuring the time was right to make a third album. I’ve written before about Depeche Mode for anniversary pieces (and more besides) here at tQ: Music for the Masses and even more relevant in this case Some Great Reward. But the latter, which has ‘People Are People’ as its almost monstrously overpowering musical highlight, is something that builds on what had already happened, it was perfection of a certain kind of form. But it didn’t come from out of the blue, and that’s where the album prior to it, 1983’s Construction Time Again and now celebrating its fortieth anniversary, needs a closer look.

For their debut singles and then album Speak & Spell, it was almost all pop fizz thanks to Vince Clarke’s songwriting and ear for sparkling accessibility, something that he immediately proved several times over with Yazoo, the Assembly and then Erasure. A Broken Frame was Depeche as tentative three piece in the studio, relying on old songs from Gore as well as new ones, seeing what exactly they could do with synths in a variety of approaches, from harmonised sunniness to murmuring ska rhythms. That release scored as it needed to. It remains an irony that because ‘See You’, the band’s first post-Clarke single, charted higher than ‘Just Can’t Get Enough’, they felt they were on the right track, when said first Gore-written single is now almost universally ignored. But the further singles went well, goofy videos and all, and Alan Wilder, having covered for Clarke on tour and gelling well enough with the rest of the band, was fully invited on board. He first appeared on the stand-alone single ‘Get The Balance Right!’, featuring some of the band’s punchiest beats set behind a naggingly addictive synth hook, and continued as part of the band for Construction Time Again, once again working with the combination of Mute label boss and producer Daniel Miller.

A further piece to the puzzle was engineer Gareth Jones, who up until that time had been closely working with Ultravox refugee John Foxx on the latter’s own solo career in the worlds of experimental and electronic pop music. Jones would later admit that whereas the more cerebrally inclined Foxx was doing work that suited his own general tastes, he thought Depeche was just, well, too pop. But Foxx himself urged Jones to give it a go at the sessions initially handled in Foxx’s own Garden studio in London, and it turned out to be a dynamite partnership that would last through 1986. Crucially, it was a time when many older pros behind the boards couldn’t get to grips with the new digital age without sounding clumsy or instantly like yesterday’s news. In contrast, the relatively young and open-minded team of Miller and Jones met Depeche right in the middle to find ways to expand on what had already happened, work with the keyboards, synthesizers and more to push them to limits rather than simply use them as sonic icing. They collectively bonded over the prospect of, ‘Well that was cool but what if we tried this?’

There was also a little fact captured by the title of the documentary film the band put together for the deluxe reissue of the album back in the 2000s: Teenagers, Growing Up, Bad Government, And All That Stuff. It’s a quote from Gahan about Gore and his songwriting focus at this point, and it captures the fact that the band, still incredibly young – the original trio was only 21 or 22, with Wilder as the ‘old man’ of the group at 24 – were indeed no longer the teens they were when Depeche as concept if not name starting coming together. Even with the pace of the recording industry being what it was, having two full albums and a slew of singles already was exception rather than rule beyond being in a band to begin with. What had essentially started as a series of lyrical ruminations on various shades of emotion was starting to show signs of wanting to tackle other ideas. Gore later said it was his observations on extremes of wealth during an Asian tour as much as the daily news in the early years of Thatcher and the last decade of the Cold War which provided much of this impulse, making it a classic case of not needing to be formally in school to shift from being seemingly apolitical to, however broadly, politicised.

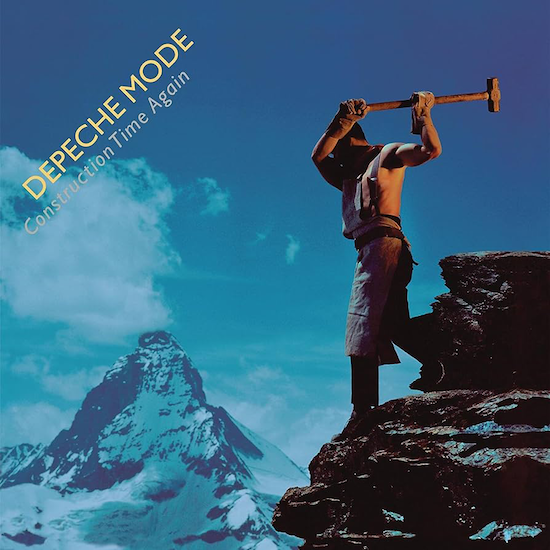

Then there were the notable graphic choices for the album and its singles. This included the second stellar album cover in a row from photographer Brian Griffin, who gave a literal interpretation of the band’s request to show a steel worker with a sledgehammer in front of a mountain – that’s not a mockup, that’s really the Matterhorn in the back of the image. This all led to a lot of press attention basically arguing for a seeming radicalism, or at least a decidedly working class/left-of-centre perspective. As Depeche’s career and impact has continued over the years, it’s more accurate to say that those who hunger for something more than what they have in their society, however defined, did respond strongly to the band, thus their massive impact among Eastern European and Russian youth circles towards the end of the 80s and beyond. It was an intensity mirrored just as much in the fans going berserk for them in the 101 concert film in hypercapitalist America. However you look at it, there’s a real theme throughout the album of taking stock of things, getting to grips. Wilder’s own songwriting contributions included the low key but baldly stated environmental anthem ‘The Landscape Is Changing’ – arguably all too perfectly resonant this decade and likely to keep being so for a while to come.

Yet this all said, singling out Depeche on this particular front among the many acts who were more clearly in that vein, at whatever measure from the centre, is a bit of a mug’s game, because the radicalism was never in Gore’s blunt lyrics but in the music itself – and massively so. There’s a potentially apocryphal Gore quote worth restating: "If you call yourself a pop band, you can get away with murder." That Depeche were already pop had been demonstrated several times over, but this is where the industrial comes in, and nobody was trying to hide it at all.

The key was ultimately not just playing keyboards and coaxing specific sounds out of them but using early sampling technology to specifically punch in sounds to treat, rework and otherwise sculpt. The sense in all discussions of that time is that everyone was up for this collectively, pushed perhaps a bit more by Wilder on the technical level but not solely. There was a flashpoint recognition that now feels incredibly obvious but then clearly still required work. It was a translation of the sonic extremity and found-sound approach that infused industrial and any number of avant-garde figures and scenes that came prior to industrial. Collaging and sampling was hardly unknown, to say the least, but to pick two examples, New York electro and early hip hop openly exploring those veins were still only starting to make its wider recorded mark, while figures like Brian Eno and David Byrne in collaboration weren’t looking for radio play per se, whatever marks they’d already made in other contexts. Depeche had already had big hits, tasted success, and wanted more, and wanted it on Top Of The Pops, but using this kind of approach.

While they used all kinds of sources – there’s mentions of random toys being brought into the studio to be sampled – they found themselves allied with some of the most literally industrial products out there, and equally some of the bands falling within the description. If the literal klings and klangs on Kraftwerk’s ‘Metal On Metal’ from Trans-Europe Express provided a clear foundation to be built on some years prior, in the early 80s bands tagged as metal bashers or the equivalent existed because that’s exactly what they did, most famously with Einstürzende Neubauten literally dragging sheets of metal on stage and into the studio to become percussion instruments. Depeche approached it in a different fashion, going around construction and industrial sites armed with sticks and hitting pipes and the like while Jones recorded it on a Stellavox tape machine. These were brought back to the studio and rework into the arrangements either as secondary or main elements, if not both.

The final kick to it all lay in the impact of the percussion – Depeche’s first two albums had their punchy moments, like the album version of ‘Photographic’ on Speak & Spell. But Construction felt big by comparison, with beats stomping harder than ever. If again there was a German ancestor to note, it was DAF, whose clipped percussion and stabbing synth bass on albums like Alles is Gut set up the idea of brute efficiency and impact in a way that was also almost hummable when not being accompanied by shouting. Depeche found a way to make the sugar and spice connect as well as contrast. Construction Time Again is anything but a continuous sonic assault, with plenty of quieter and more restrained songs amid higher-volume bangers, but, in this way, one feels things all the more. In that documentary film, Jones notes how parts weren’t simply directly recorded onto tape from the synths but fed through amplifiers first – you feel things resonate against walls and surfaces.

And so, boil it all down: a line up of Gahan on lead vocals, Gore on harmonies and occasional lead turn, keyboards and overall songwriting, Fletcher as keyboardist and general vibe merchant and Wilder as the proper musically trained addition, performing songs with lots of melodic hooks that aim to connect immediately. Pop. Industrial. Man and machine indeed. Construction Time Again lives and breathes and rings and shatters. There’s careening freneticism with ‘More Than A Party’, one of Gore’s earliest full-on sex-and-guilt lyrics in the moody flow of ‘Shame’, another Wilder-written effort in ‘Two Minute Warning’, with a more-complex-than-it-seems arrangement really going to town, especially on the chorus, the concluding contemplation with a subtle but clear punch ‘And Then…’ Nearly song for song those building site samples and more come to the fore, sometimes unavoidable, sometimes snaking around a central rhythm or melody. ‘Shame’ is especially great in this regard, adding more elements as it goes to the verses without overwhelming them, stripping back on the chorus before they all hit again – and even throwing in the kind of frenetic flute sound that would soon be a calling card for noted Depeche fan Robert Smith more than a few times over the next couple of years.

This album really does sound like a series of machines suddenly activated and set in motion. Some Great Reward expanded on the trend but this is where the model emerges in full, with the secret always being the idea that there’s something about a good damn rhythm. This isn’t Kraftwerkian so-stiff-it’s-funky; for all that there was rage generated among those who were stuck on ideas of authenticity and realness, what was truer was how the heavier songs delivered those big beats and played with them. One of ‘More Than A Party’s best moments comes right at the end when the rhythm relentlessly accelerates while Gahan’s voice doesn’t, leading to a sudden click and break that settles into the rattling train noises that introduces ‘Pipeline’. Perhaps the most literally industrial pop song of the entire album, with a lyric based around, indeed, construction time again if on a metaphorical level, it really does feel like a work song, a slow slamming main beat, counterpoint bangings and scrapes and clatters in place as it goes. In the seeming centre of it all, Gore’s lead vocal, recorded live under a train arch while the music itself played from another speaker, feels like a slightly muffled voice reaching through the gears, Gahan and others joining in on the titular lines as a chorus. At the time it might have been seen or heard as a cousin to something like Spandau Ballet’s ‘Musclebound’. Now it feels like a perfect radio drama in miniature, something that the BBC Radiophonic Workshop would have killed for, and it comfortably lets its arrangement play out well beyond the final sung words, a pleasure in its own creation.

The album had only two singles. The second appeared after its release and rather lives in its shadow; it’s not really the preamble to Construction as such but the opening number ‘Love, In Itself’ serves as a handy introduction or reintroduction if you prefer to the band in general. Gahan’s playing with his vocals on the verses, more of a distinct twist to his voice, something that easily contrasts with his more commanding tone on the choruses. What makes it work is how things play around the arrangement, the sudden drop-ins of piano and acoustic guitar on the break, not to mention the sudden finger-click, the shadings and textures that drop in and out throughout the song, warm bell tones ringing through the choruses, a suddenly looped and treated vocal snippet. If you knew nothing about the group other than the stereotype of their sound, ‘Love, In Itself’ is the song you might imagine, but it still works.

But there was another single, the one that came before the album’s release. I mentioned ‘People Are People’ earlier because it is indeed that massive and that amazing, a sonic culmination of what they achieved with this album turned into monumentalism so perfect even America couldn’t deny it, though the really big hits there came some time later. But ‘Everything Counts’ is the blueprint, charting at number six in the UK and scoring high placements elsewhere in Europe. The fact that it’s the one that Depeche still happily play on tour while ‘People’ hasn’t been touched in decades is telling. That amazing scraping sound alone at the beginning just behind in the mix of those massive beats is still a wonder, and a classic accident. Miller revealed years later that they were simply playing around with some equipment and that was the result.

‘Everything Counts’ contains music box melodies plus the sounds of sparkling chimes and reedy melodicas while the bass and beats pound in dancefloor command. Meantime, Gore’s lyric was, well, capitalism summed up, handshakes sealing contracts, a career in Korea being insincere, everything counts in large amounts. It was pure x = x, it wasn’t Das Kapital or even trying to be, it just said ‘here it is’ and rhymed while it was at it. But Gahan delivered the verses with a commanding glower, Wilder adding in lyrical repetitions here and there just so in live performance, while Gore’s sweet vocals took the chorus to another level, a serene brightness that masked the bitterness and turned it all into a playground chant. Five years later, as 101 showed, a crowd of seventy-thousand people in the Rose Bowl absolutely would not let them go, singing that chorus again and again and again even after the band had fully stopped. That doesn’t happen without a hard connection.

When you hear the album again, especially now, things that were obvious enough even a few years removed from its release suddenly become crystalline. Calling it the Sgt. Pepper’s of a genre forces an unsustainable comparison, but in a weird way it’s still apt: a young band with key studio cohorts after initial hits taking stock of both peers and forebears, pushing the use of new technology to expand possibilities, try a variety of sonic and lyrical approaches beyond what they’ve done before while never ignoring a good melody. You hear the sense of ambition being realised and paths previously unseen opening up, the more so because for all that synth pop’s initial towering reign was still in effect, the band weren’t trying to be robots or angular Bowie clones in presentation; they were just some young guys starting to play around with their earlier club kids on the make image. It was reachable, and it was relatable.

Peers recognised it quickly enough, even if they were on their own paths. Indeed, it’s notable how many bands that would later seek set themselves apart from Depeche, either implicitly or with intent, were essentially taking possibilities from the album for themselves on the way. Al Jourgensen of Ministry perhaps most notably did this, with 1986’s Twitch being a bridge to the future that existed in part because of Construction‘s clear example, but also Front 242 in Belgium and Skinny Puppy in Canada, to name just three bands of many in what would be a burgeoning subgenre. At home Nitzer Ebb found themselves with a supporter in Wilder and a home on Mute itself, their own brute way around iconography and delivery certainly not far removed from DAF, but also not too distant from this album in particular. In (then West) Germany, to name just one example there, Camouflage formed in 1983, inspired by plenty in the field – their name was a Yellow Magic Orchestra reference for a reason – but in the ensuing years making a mark at home and abroad due to Depeche’s own massive impact that Construction laid the groundwork for, placing top ten in the country at the time.

As for descendants? That Trent Reznor was a Depeche fanatic wasn’t merely obvious but intrinsic by the time of Pretty Hate Machine‘s appearance as the Nine Inch Nails debut album in 1989; for all the metal moves and wild screeching intensity, the layers of beats and sounds and hooks came from Construction and what followed, a key factor in Reznor’s initial successes even well before ‘Closer’ broke things bigger years later, especially given a synth line that sounded like a distorted angry cousin to ‘Get The Balance Right!’ And speaking of that song? In that previously mentioned documentary Derrick May praises it in particular but talks about Depeche in that era pointing a clear way for Juan Atkins and himself to follow with Detroit techno. Construction‘s open embrace of the possibilities of the dancefloor and what could be added to became a signal across the water. As the decade went on, anything remotely falling under the rubric of industrial-inclined or aggressive electronic dance, especially if there were sharper lyrics on a social front, felt like it was in conversation with Depeche and Construction, whether intended or not.

To play out all the continuities from there is too much for a piece like this to bear, but here’s a way to think about it – in 2011, Carly Rae Jepsen’s ‘Call Me Maybe’ was a monster fluke worldwide hit, something she’s never repeated despite recording a truly remarkable and enjoyable series of albums and singles since (seriously, any live performance will not leave you in doubt on the matter). At some point, a clever mashup emerged, putting its music together with Nine Inch Nails’s early landmark ‘Head Like A Hole.’ The Jepsen original itself had been engineered by fellow Canadian Dave Oglivie – a long time collaborator with Skinny Puppy – and the rhythmic punch of the original, even more so in the mashup, was very much industrial pop. It doesn’t all automatically trace back to those six guys in a room in London, certainly, but you can see how it all flows regardless, the idea that you could be massive in sound and scope, mechanical in intent and feel, warmly human in delivery and voice and lyric. Who invented industrial music? Really, who cares? But who made it something that could find a place on the radio, on TV, in arenas? Hey, it’s a competitive world, yet it’s clear which hands grabbed most quickly.