Weirdly enough, it’s almost ignored.

Which is a very strange thing to say about an album called, however much in jest, Music For The Masses. You’d think that Depeche Mode’s sixth studio album in seven years might get a little more attention. But here’s an illustrative point: last decade, when the entirety of Depeche’s work over its first two decades was reissued with, among other things, bonus DVDs containing a multi-part documentary series, the one with Music only talked a little about said album. There’s some good anecdotes, don’t get me wrong, but the majority of it talked more about the tour and D. A. Pennebaker’s still-brilliant 101 concert film, not to mention the massive Rose Bowl show featured in said film. In comparison to the heavily detailed, intriguing documentary on Black Celebration, the album previous to Music, I remembered wishing there was something more.

Music isn’t a red-headed stepchild or anything in Depecheworld, don’t get me wrong there. We are talking about the album with two of its most defining songs on it – the monstrous ‘Never Let Me Down Again’ and the propulsive ‘Behind The Wheel,’ about which plenty more to say later. But from a distance it almost feels a bit lost in the shadows of two crystallisations of the evolving story of the band. There was 1986’s Black Celebration, the clear pivot and shift from an often more frenetic/industrial-electronic approach to something starting to hint at arena-rock aesthetics. It had a looming, brooding darkness on multiple levels but was still, for any number of listeners and bands that followed in its wake, a high water mark across the board. Then, of course, Violator in 1990, almost talked into the ground at this point but undeniably the moment where after a decade of building things up Depeche vaulted into the realms that they’ve never quite left since, smash hits worldwide, a knack for hooks perfected, an electronic/rock fusion that was also the beginning of the full turn towards being a true electronic rock band, albeit without a bassist.

Caught between the two, and sharing the light with 101, Music For The Masses isn’t a small album, nor is it a weak one. From an increasing distance, though, it feels underrated – which may be a surprise to anyone in the crowd shown in 101, listening to Los Angeles’s powerhouse station KROQ spinning songs from it constantly, attending that Rose Bowl show. I didn’t go myself – 1988 was the year I fully got into the band, and living some hours away I hadn’t put it together to see about going to the show until it was too late – but when I started at UCLA later that year, it seemed like everyone in my dorm who was local to the area had been to the show and had bought approximately eight million T-shirts. Each. Depeche wasn’t the only major musical force in the inescapable air at that time and place – add on Guns N’ Roses getting a lot of attention, not to mention NWA and Jane’s Addiction hot on their heels. But all those bands were local, among many others; Depeche, though…they were that big and that unifying, from thousands of miles away.

Depeche as a unit came into Music on a roll, Black Celebration having started to really cement a subcultural impact in America beyond early pockets of fandom and the fluke top 40 success of ‘People Are People.’ They’d also just started filming videos with Anton Corbijn, who immediately took the band well beyond both their goofily dorky start in that field as well as the often too earnestly clunky examples from the mid-80s. It was just enough of an experimental/European art film aesthetic at work to stand out from a lot of the crowd then, both in ‘modern rock’ or however the term was used and in MTV’s wide reach as a whole. Finally, in a sharp move, they’d taken note of another breakout American success story: Tears for Fears, whose Songs From The Big Chair had dominated almost everywhere in 1985 and 1986. Dave Bascombe, whose engineering work on those sessions emphasised the big, sweeping and pounding, was recruited as producer, taking over from early stalwart Gareth Jones; for the first time Mute label head Daniel Miller didn’t feel he needed to be there to help on coproduction.

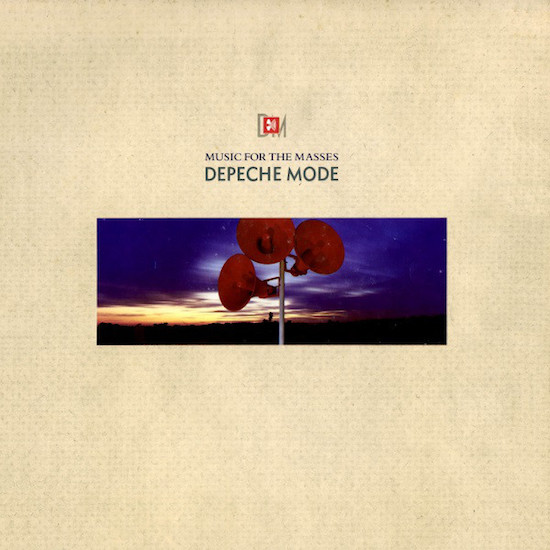

‘Strangelove’ slipped out as an early single while sessions were still ongoing; as first heard it was aggressive synth-funk that was almost…sprightly. Which both worked and didn’t, as later versions of the song would demonstrate over the next eighteen months. Still, it helped set the overall tone of things to come, with the Corbijn video fully showcasing the director’s eye for odd, intriguing visuals shot through with humour and barely concealed lust, while the sleeve provided the first hint of the Martyn Atkins-created visual hook for the album: a closeup of a red megaphone, with the slightly unexpected logo of ‘BONG 13.’ But when ‘Never Let Me Down Again’ was released as the next single shortly before the album’s full release, the sense of what Depeche and company could really do, and where they were at, was now absolutely set.

Black Celebration had admittedly already started to set particular tones in this front, and similarly its leadoff single, ‘Stripped,’ was a clear declaration of intent, emphasising growling machinery, a sense of vast space, explosions and emotion. It was arguably them vaulting up to the bigger venues they’d play on that tour. So maybe ‘Never Let Me Down Again’ acts as the signal in advance that yes, they COULD play the Rose Bowl – and they of course did, and the scene where, during a performance of said song, Dave Gahan, isolated in a spotlight, demonstrates the now-expected back-and-forth arm wave, only for the lights to go up to show thousands of people in the stands doing just that, remains one of those moments that’s amazing, chilling and compelling all at once. In the commentary for the DVD release of the film, Gahan marvels about that and the song itself, saying that its overwhelming arrangement feels almost like Wagner, and he’s not wrong, really. (More on Wagnerian associations at the end, though.)

The impact, though, almost obscures the obsessive detail in the song – like the best of such constructions, more emerges each time you give it a relisten. This isn’t even referring some of the best remixes of it from the time as well, adding new moments of awe. Arguably the lyrical scenario is simply ‘Waiting For The Man’ by the Velvet Underground twenty years on and depersonalised, hidden in language that suggests rather than spells out – the narrative voice isn’t interested in the details of who provides the fix and where to go, it’s all about the experience, and even that could be seen strictly in the realm of twisted romance. Martin Gore’s lyric does also provide what for a lot of people has been a big lyrical stick to beat him and the band with since – the rhyme of ‘houses’ and ‘trousers’ – but me, I kinda love it. Gore’s gift for the big blunt hook means just that, and you have to buy into all of it for it to work.

If it was just that, though, it could simply be a rumination on surrender and control. ‘Never Let Me Down Again’ doesn’t ruminate, though, it dominates. From the start – the rising guitar hook provides something quick and seemingly quiet, but then the first beat kicks in and pretty much it’s almost all over from the start: the hook disappears and recurs, synth and piano melodies pound out, distant slow bass parts provide a murky undertow, Gahan sounds almost innocent and happy as much as he sounds desperate. Yet for all the obsessive focus the song presents, it also provides variety. By the second verse, there’s a new rhythm pattern that subtly kicks in over the main one, a gently raspy overlay; Gore’s backing vocal steps in and out of the background behind Gahan, appearing in full at the end with the sing-song romance-as-delusion “See the stars, they’re shining bright/Everything’s all right tonight.” When those buried orchestral swells and weird wordless cries – if they are that – first appear at the end, the whole thing becomes a tight loop/effect that is as much grandeur in sound as anything Phil Spector did at his most opulent.

Meanwhile, while I wouldn’t go so far as to call it a concept at work, it’s a little telling that the other major single from the album played out the sense of going for a ride with someone that’s calling the shots, only in a much more literal car-related sense. As with ‘Never Let Me Down Again,’ ‘Behind The Wheel’ is fairly obviously so much metaphor as any number of car-related songs in 20th century pop history has been. If the Smiths’s then-year-old ‘There Is a Light That Never Goes Out’ was more directly about a particular scenario and desperation – “take me anywhere, I don’t care!” counterbalanced with a “strange fear” – ‘Behind The Wheel’ was well beyond that fear stage. The desperation may have been there in the “I’ll do anything…please!” but it was all said-as-much-as-sung with a purring, knowing confidence from Gahan, that instead of having to convince someone of something, two people knew exactly where they need to be right at that moment.

It was also a real sign of the musical moment as well that a rattling hubcap in perfect stereo could serve as an opening hook. I don’t know how many times I heard ‘Behind The Wheel’ when I got that single but it was also the first Depeche single I did ever get and I think I warped the vinyl after all the plays. Motorik-as-disco-as-techno-as-involved overlay of about three or four different synth melodies and loops and also this basic as hell guitar part which, it turned out, was all that was needed. In an era where the Sunset Strip shredder stereotype was fully in gear thanks to the impact of Eddie van Halen in particular, it’s like Gore loved playing anti-solos – why make a mess when you could have absolute focus? The whole song works on the principle of interlocking parts, a construction at full function, a tension that never truly resolves: flamenco handclaps as martial beats, gear shifts as machines exhaling, more synths as a queasy orchestration, vocal snippets brutally cut into a loop. And even one actual car part in stereo. To make a comparison to a Depeche hero: ‘The Passenger’ was about watching everything and thinking it looked good, but Iggy Pop was still in control. As a whole ‘Behind The Wheel’ is about losing control and loving every goddamn minute of it, surrender to the other and the arrangement.

As for ‘Strangelove,’ the album version beats out the earlier single version to the moon and back. Whether it was about taking a little more time to play around with the arrangement or just the space that an album approach allowed – and maybe it was just about sequencing too – it’s a much different beast here. On an album where strong, unique song beginnings are key, it’s another success, starting with a quiet machine gear loop noise, almost like a more abstract version of the engine chug that underscores ‘Stripped,’ along with a barely audible bell-like synth part. Then the already familiar triple-pound BAM BAM BAM from the single version arrives and suddenly it pulls back once more, but into something else: bass and beats that in its brute simplicity could be, say, Prince on tour 1984 in eastern Europe, if that had been allowed back then. Or maybe call it Motown 1971 after the apocalypse when the robots took over.

The song essentially breathes more, so when the full hooks begin everything has felt like it’s built up to a moment rather than being slammed directly into it. No problem with the latter approach, of course, but as both ‘Never Let Me Down Again’ and ‘Behind The Wheel’ had demonstrated, there’s something to be said for the monumentalism to grow a bit rather than completely crash onto a listener. Gore’s guitar on this one is subtle compared to those songs, but like on so many later compositions it’s this lovely shading, hiding out amid the strident synth riff that’s this unmissable nag nag nag. I like how at the end there’s a part where Gahan calls and responds to himself and then suddenly, based on where his voice ‘should’ be per what’s already been performed, a sudden high synth bit squirrels across the mix. It’s that sense of things being just off-kilter – or just human – enough that helps Music throughout.

What makes Music For The Masses hold together as an album, though, isn’t just those singles, strong as they are. It’s also the still-in-sync band dynamic of the period, with Alan Wilder’s ear for not only his own performances but the possibilities in terms of sound and arrangement coming ever more to the fore. The reissue documentary helps spell this out further, with both Wilder and Bascombe happily talking about their experimenting with creating new sounds, from instruments and from other sources, and Gahan’s effusive praise for Wilder’s abilities all around. Combine that with Black Celebration’s having clearly shown – especially on its second side – how fragmentary, shorter or more cryptic and understated songs were as much something in the general Depeche toolbox as a chartbound stomp, and Music was in ways the slightly more polished version of that approach, just. Not quite as much, granted, and some songs here are more enjoyable rather than distinct – ‘Nothing’ in particular almost could be a throwaway, suggesting a Depeche from two years back sonically, even if Gahan’s vocals showed it wasn’t that entirely.

But there’s plenty of instances of “what if we do this – wait this is brilliant!” happening almost song for song. Consider how the there-is-no-subtext-here ‘I Want You Now’ invents Timbaland’s approach about a decade before he helped rewrite pop. Okay, a bit extreme, but then again: for a while there, he often got reactions, understandable ones too, along the lines of "Wow, a drawn breath as a rhythm and a sample on an r&b and pop hit!" ‘I Want You Now’ has several hums and gasps – male and female, sampled, per the previously mentioned documentary, from a very naughty film, shall we say – interwoven around each other, around accordion as well, Gore’s vocals rising through the minimal synth line, sudden dramatic silences, a random unsettling burst of laughter, a siren loop, wordless keening overdubs. To say it’s all very filthy is a compliment, to say it’s a great song to sing along to even more of one. There’s also, from start to stop, a steady wheezing back and forth that sounds even more like someone in a kind of extremis of the pleasurable kind. Turns out this was that previously mentioned accordion – only in this case, modified so instead of the familiar sound of the instrument it’s simply the air moving in and out of it, recorded and looped.

Then there’s ‘Little 15,’ a song whose lyrical meaning I still haven’t been able to exactly figure out after thirty years – cryptic romance? transposed wish fulfilment? – but musically, per Wilder’s comments, it takes inspiration from Michael Nyman’s score for Peter Greenaway’s A Zed And Two Noughts. There weren’t many bands trying to do that then or now, much less an emerging superstar act, and taking that idea where it might go. For starters, what the hell IS the opening loop on the song? Strings and music box? Speaking for myself, it’s all about the first time that the string part appears in full, and then how that descending piano line heralds this quiet second melody which in turn heralds the from-the-mountaintop drums and then this break that’s suddenly pure cinematic romantic elegant gloom, like the train broke down in the Alps or the Carpathians and the Russian winter is about to take over the land and everyone is resigned to their fate. By the end of the song everything’s about as detailed as a Bomb Squad mix, not that most people would ever admit to that. And this is a ballad!

There’s more to be said about pretty much all the other songs in turn, how they often bleed into one another rather than existing discretely, helping to create a mood or maintain it – or even subvert it, as with ‘The Things You Said,’ a complete turnaround from the immediately preceding ‘Never Let Me Down Again.’ A Gore-sung ballad with a long whisper/sigh leading into a low, quietly relentless bassline, distant star-twinkle melodies, murky backwards-run instrumental moments, emotional brinksmanship, a last isolated overdubbed "They know me better than that…" – it’s anything but a simple song in its careful layering. Later there’s ‘To Have And To Hold,’ in ways the logical extension of Some Great Reward’s blackly cynical cover photo, only here perhaps positing some sort of relationship, marriage or otherwise, as an anchor and a way out of hell. Except it sounds like a long slow slide into hell from the start, not a traditional pop song as such, it has no chorus, it’s just one verse, one slow, spiralling downward, grinding, dark, monumental, dour, desperate crawl out of the pit because it’s all over verse. Piano lines sneak around Gahan’s vocals, quiet counterpoints slide beneath them. When the Deftones ended up covering Depeche for a tribute album, this is the song they chose – and that immediately earned my respect. You have be a stone-cold fan to know this one, and to love it.

Finally, meanwhile, there’s the instrumental song that ends the album but was also the original B-side to ‘Strangelove.’ Logically, therefore, this song is based around a piano part that’s attractive as well as a little ominous, that slowly and carefully adds on barely audible bells and a stentorian three note/beat bass/drum/more piano ‘begin the pagan fires for the blood ceremony!’ rhythm and then high and slightly tortured sounding strings and a contrasting low/high/low/high near-wordless vocal exercise and then MORE bells sounding like the chimes of doom and cymbal splashes and then Valkyries keening on high and then demented church organ loops and the sense that perhaps Gotterdammerung might actually be heralded by some dudes from Basildon and then there’s an echoing stop. The fact that it’s called ‘Pimpf’ – a German language term for male youth that was eventually used to refer the youngest cohort of the Hitler Youth organization – almost seems to explain itself. But given recent history – including Gahan’s inspirational verbal trashing this year of neo-Nazi/alt-right type Richard Spencer, who had claimed Depeche was the representative band of his ‘movement’ – you can sense from a distance how what must have been more of an ironic, perhaps too glib, reference on an album shot through with monumentalism evoking a particular style and appearance takes on unavoidable shades.

Still, the conscious idea of performative interpretation of arena rock as fascist rally had long been kicking around already at that point – just ask Roger Waters for a start – and I tend to think of ‘Pimpf’ as less of extended melodrama and black joke as I do of it as it functions in 101, both film and the accompanying live album, where it was the band’s intro music for the tour, never performed live but always one heck of a way to rabble rouse. And in the film, I just think of the band making their way out to the main stage, Gahan with a drink in hand, all of them looking a little tired and maybe a bit nervous, their big bet that they could do the Rose Bowl actually happening, thousands upon thousands upon thousands of people waiting to sing along to every word. As I’ve marvelled at more than once, this era, and that show and that film, underscore something important: Violator may have finally cemented Depeche Mode’s place as a unique act, a fusion and extension of multiple impulses that created a new sonic blueprint for many more to follow, but the band that recorded Music For The Masses and took it on tour, and the fans who listened and followed them, none of them knew Violator or Songs Of Faith And Devotion or everything else that was to come would happen the way it did. Depeche were already that, indeed, massive, building and bursting out to the world on its own terms. Violator underscored it – Music For The Masses proved it.

One last note on the album: following ‘Pimpf’’s dramatic conclusion and a pause of a few seconds, there’s a final snippet of clinked bottles and a door closing and feet walking over a bit of mournful strings once again caught in a loop that appears after a few seconds. Who needs a high tone only dogs can hear to end a record?