We all remember the piercing call that drives ‘Smalltown Boy’, Bronski Beat’s debut single: that soaring note of release which turns out to be a wail of pain, the word “cry” sublimated into a sky-high sound? It’s characteristic of Jimmy Somerville that his signature cry is both wounded and freeing: ‘Smalltown Boy’ is a tale of persecution and homophobia, but its descriptions of pain are nestled into the comfort of Somerville’s voice. Within that flying voice – and the propulsive hook which fires underneath it – comes the possibility of relief.

It is one of pop’s great voices, with the necessary strangeness that separates the haunting from the merely virtuosic. Somerville’s counter-tenor has such an immediate impact on the skin that it never seems like a display of technique. It can be a voice of chilly affect or acute sensibility: either way, you get pinpricks from the feeling of extreme sensitivity being exposed.

With the runaway train of the chorus, Somerville’s voice escalates, creating space and distance from the trauma of the verses (“Pushed around and kicked around, always a lonely boy”). The singer’s tone toughens in resolve, occasionally rising to a feisty growl (“And as hard as they would try / They’d hurt to make you cry”), so that we feel the slight lick of flame within his otherwise cool voice.

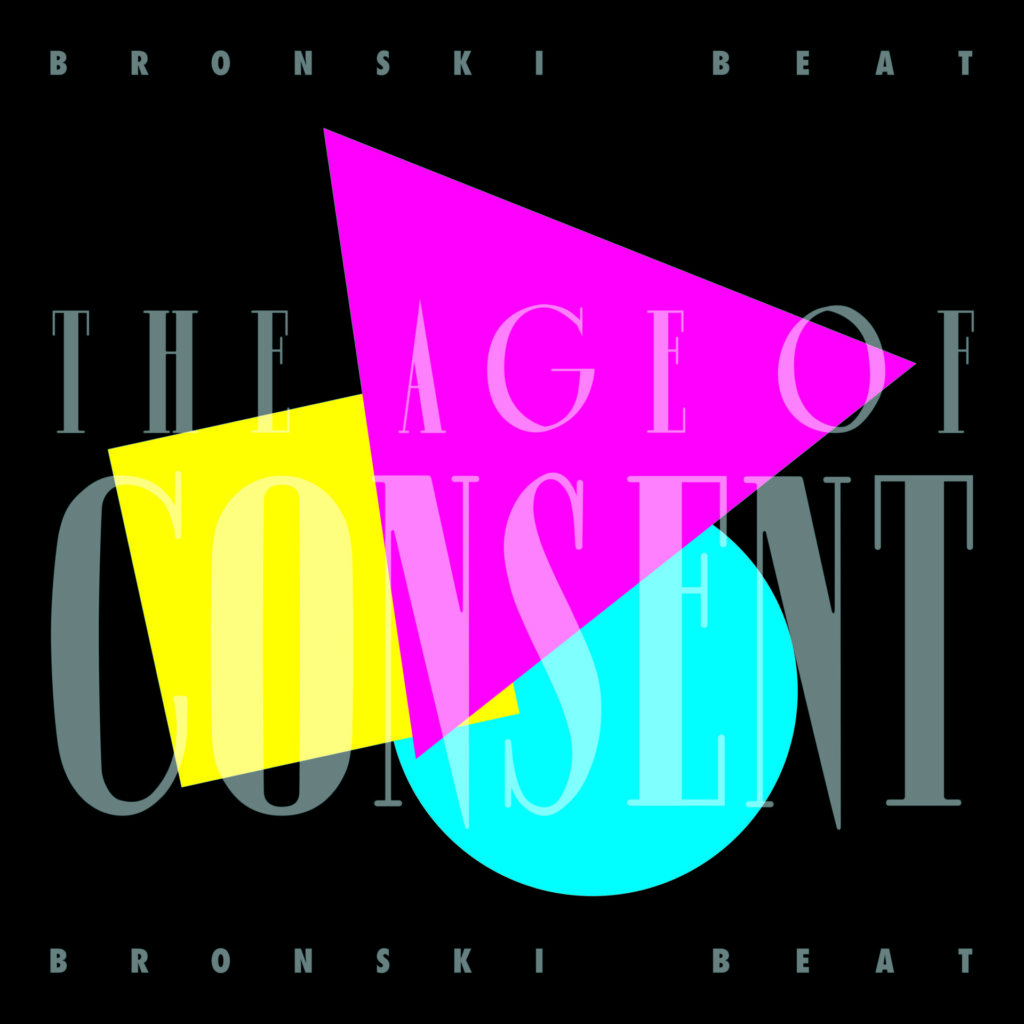

At the same time, there is a wintry numbness to the track, and to most of this album: the sound of starkness and desertion even as escape beckons. The Age of Consent is built on such contrasts: between energy and fatigue, sensuality and introversion, and furious desire and its suppression. On ‘Screaming’, the narrator has pounding recollections of abuse which seem eerily distant, as if the hurt is being perceived through a layer of ice or anaesthetic.

‘Smalltown Boy’ is both melancholy and compulsively danceable: Somerville’s plaintive voice evokes the suburban wastes of his childhood, even as the racing chorus pushes us further and further away from those memories. If there’s one mood I associate with Bronski Beat, it’s bleak joy: the sense of sunshine being filtered through a black-and-white screen, a world flowering in desolation.

Robert Christgau has criticised The Age of Consent for being “monochromatic” and having a “narrow dynamic range”, but it is precisely this focus on an oppressive atmosphere – and the refusal to look away – that makes the record so striking. Throughout the album, passions are tempered by caution and restraint. No matter how addictive the beats and rhythms of ‘Smalltown Boy’ are, the texture of Somerville’s voice primes us to react to the music with a certain delay, as if hesitating before diving into headlong movement.

Bronski Beat’s version of the Gershwins’ ‘It Ain’t Necessarily So’ is similarly muted at the start: it opens with the beguiling, twisting sounds of Richard Coles’ clarinet, like a serpent winding its way into our confidences (Coles was later to become a reverend and the self-described “go-to gay” vicar for the press). A soft-voiced Somerville emerges as a new kind of preacher, subtle and coaxing. He begins with an unnaturally precise rendering of a scat (“Da ra da am de ra am de”), as though an unlikely bunch of sounds has been forced into memory.

As it turns out, rote learning is the subject of the day, which this wily serpent dares to question: “The things that you’re liable / To read in the Bible / It ain’t necessarily so”. A series of tall tales follows: David and Goliath, Jonah and the whale, and most pertinently, the Pharaoh’s daughter claiming to have fished Moses from a stream. They are all legends which conveniently omit the reality of the body – and in the latter case, may serve as a cover for illicit desire. The speaker doesn’t presume to overturn orthodoxy, only to introduce an element of doubt: “it ain’t necessarily so”.

Compared with other interpreters of the song, Somerville is fairly subdued here: his voice remains angelically pure instead of dishing the dirt on the Pharoah’s daughter. He doesn’t play the huckster or hepcat like Sammy Davis Jr, nor does he go to town with innuendo in the style of Diahann Carroll or Lena Horne. This isn’t the grand rendition offered by Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald. But maybe, in its small, humble way, the serpent has a point: these are improbable yet “universal” stories that we’ve been asked to swallow. Which begs the question: why aren’t other people’s stories taken on faith?

Somerville’s coolness is instrumental in discreetly suggesting an alternative point of view: that the Bible is an outrageous, provocative read, the kind of hot stuff you’re “liable” to believe. Perhaps the devil’s advocate is only proposing common sense? By the second half of the song, he finds a rising tide of support: Somerville is backed by the Pink Singers, London’s renowned LGBTQ+ choir, who echo the changing of consensus. Their delivery is as easy and natural as the rolling of the word “necessarily”: smooth and undulating, like the serpent whose only crime is asking you to think for yourself.

With the cover versions on this album, Bronski Beat seemed to relish giving new shades to the American songbook through their renditions of jazz and dance standards. The Age of Consent does contain one original jazz track: ‘Heatwave’ is a classic throwback number, complete with a meticulous tap routine performed throughout. The title is misleading when it comes to temperature; the lyrics conjure an idyll of “tattoos and muscle, passion and sweat”, but this excitement is envisioned rather than sensed. There’s a definite chill in the air: the polished taps and sharply individualized sounds create an impression of distance rather than coming together. The singer dreams of warmth and physical abandon, but the vibe is more of a shivery “don’t touch”, in keeping with the climate of anti-gay policing in mid-80s Britain. ‘Heatwave’ imagines a summer of sexual freedom, but what are the odds of such a paradise existing in Thatcher’s UK, without being criminalised? Not a snowball’s chance in hell.

It’s on the final track, a cover of Donna Summer and Giorgio Moroder’s disco classic ‘I Feel Love’, that Somerville’s voice turns smouldering heat into an ice burn. This version retains the thrilled, ecstatic whorl of a Moroder soundscape, but where Summer evoked a woman melting with lust, Somerville sounds frozen, transfixed by desire; the interpolation of the ghost song ‘Johnny Remember Me’ takes us into spectral territory, a love stopped in time. It’s a combination that induces cold sweat more than feverish longing, but Bronski Beat have a sensuous surprise for the ending: a lush refrain of Summer and Moroder’s ‘Love To Love You Baby’, the title phrase drawn out with cat-like mewling. Somerville’s final “baby” is so tactile that it’s as if you can feel every edge of his lip-print scalded onto the record. What a lovely way to burn.