A song drifts across a creaking wooden stage and through the side exit of a pub. I see the singer’s feet shift to accommodate the splayed legs of a microphone stand. Black gaffer tape criss crosses the floor, holding smooth cables in place. A strange space-age rocket-like instrument – I later learn it is a theremin – awaits lift-off. The singer’s voice is sweet, humble, like a perfect piece of fruit. I try to pick out the words. “What’s the point in wasting time on people that you’ll never know?” I find myself staring into a snow globe that seems to contain all the good bits of the 1960s: a Farfisa organ in dark orange with black and white key colours inverted, Joe Meek’s DIY sound-proofing panels and Dusty Springfield’s perfect blend of sadness and spring flowers.

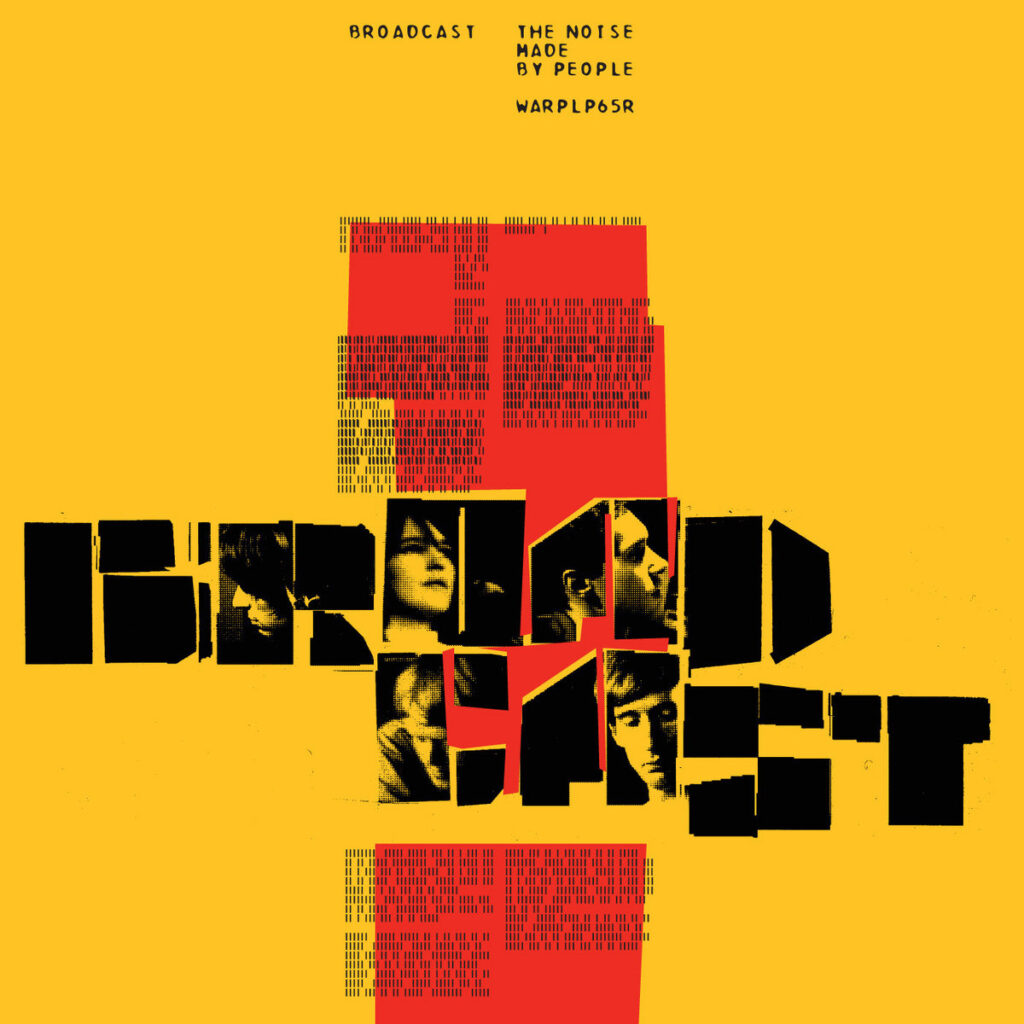

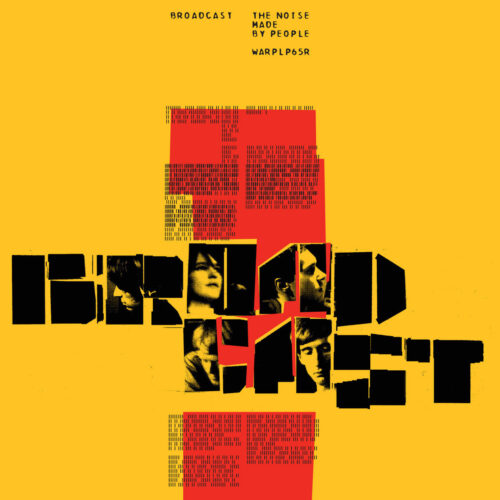

It is Trish Keenan through the gap in the door and she is rehearsing Broadcast’s melodic and windswept ‘Come On Let’s Go’ at the Duchess pub venue in Leeds, my home city’s once beloved temple of alternative music. Something like a harpsichord bounces across skittering drum beats as she runs through the second verse. The track is the “hit” (it reached number 82 in the UK chart, their highest-ranking single) from the band’s long-awaited debut LP The Noise Made By People, which, we don’t know yet, is the first instalment in a near-perfect trio of albums. A new millennium has just begun and the future is still ours; Broadcast send the sound of the old century along a light beam, an entanglement of cheap analogue synths, modulators and effects pedals and – very kindly – they take me with them.

That afternoon I creep into a low-lit back room feeling shy and star-struck, my student reporter Dictaphone in hand, and I find that Keenan is exercising her voice and does not want to be interrupted. She is singing scales along to a piano backing track that is playing from a 1970s police interview-style cassette recorder; flat and rectangular, silver-grey with oblong-shaped plastic buttons. You do not have to say anything. But it may harm your defence if you do not mention when questioned something which you later rely on in court. I am a trespasser and I can’t quite believe I am allowed to be here, observing what seems to be a most intimate part of her pre-show routine.

When we finally sit down to chat about the album, alongside her bandmate and partner James Cargill, Trish’s hypnotic singing vowels morph into gentle, more downbeat Brummy. I relax a bit and take my place at a round pub table that is varnished with fag burns. “Are we getting chips?” Trish asked James. “Do you want some too?” she asks me. “Um, yes please,” I reply. Being a student I don’t want to miss a free dinner but it also feels like a moment of trust and, between carefully scooped dollops of ketchup, I enter the magical world of Broadcast.

Our chat revolves around James and Trish’s passion for finding old instruments and trying to bring them back to life, sometimes using them half broken just to see what happens. The conversation animates around discussion of 1960s electronica pioneer Delia Derbyshire and her work with the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. I ask the pair if they are fans of fellow vintage keyboard magpies Stereolab and yes they are, obviously. And I find out more about the mysterious wand-like theremin, which later Trish commands in swooshing, mesmeric moves while inviting audience members in the front row to reach up and play it too. It is a witchy piece of kit and it gives the gig a mood of seance. Spooky and slightly demonic, The Noise Made By People recalls the eerie psychedelia of a Wicker Man procession – so much so, they became part of a ghostly new musical genre: hauntology.

I review The Noise Made By People in time for the 24 March 2000 edition of Leeds Student newspaper, which lands in inky piles around the union on a Friday morning. I describe the album’s retro appeal as “like stumbling across a dusty box of Stickle Bricks in the garage” and Keenan’s vocals as “glacial yet warm-hearted”. I remember tapping out my words while hunched over a computer in the university’s Edward Boyle Library, a brutalist structure that slams through the lower campus with a giant foot of heavy concrete. Tall glass windows allowed in the light but I generally worked there into the darkness, my tottering pile of CDs incongruous among the medical students and their books about the nervous system. I write about the images conjured by this strange album – cooling towers groaning in the twilight of a June evening – and compare Broadcast’s sound to both Italian composer Ennio Morricone and nineties art-pop weirdsters Add N to (X). I love the album and give it five stars.

In the early noughties, I still believed that new favourite bands were waiting around every corner; you just had to look out for them, poised to make them yours. Little did I know that everything was about to slide into the brain mush of the internet and its endless fragments of music consumed via streaming; albums rarely heard whole, and never made truly familiar by the flipping of A to B. Nor did I know that the already historic figure of Morricone, whose brooding movie swagger can be heard all over tracks like ‘Dead The Long Year’, would outlive Keenan by nine years.

As everyone knows the year 2000 was really still the 1990s, with the grim slow-motion footage of New York’s twin towers falling to the ground on 9/11 in 2001 denoting the true bookmark between the decades. But despite our music stars having mostly gone mad by then (a Brit Awards bum wiggle here, a Rolls-Royce in a swimming pool there), the end of the nineties remained a time of optimism and diversity. As a music fan, you could be “carrot picking” one minute (how I learned to dance to drum & bass), stroking your chin to a Boards Of Canada chord change the next, and still have room to care about Blur’s new single.

The influence of the movies on The Noise Made By People is often close, whether it’s Morricone again or a flirt with the epic aural landscapes of John Barry. More often, the noises made by the band belong to oblique European cinema, the type we used to find out about via good posters in the foyers of small cinemas. ‘Papercuts’ evokes a story in which the main character stares forlornly from the top of a Czech tower block. “So every night, when stars come out/ I try to read your personality,” sings Keenan, followed by a line which feels both wistful, and exactly the kind of thing we used to say before the ruinous age of the smartphone: “You said you wrote a page about me in your diary.” Later, the metallic ‘Tower Of Our Tuning’ and ‘City In Progress’ chug and hum with industry, and might be the soundtrack to a particularly productive day for Birmingham’s urban planners.

Before I leave the room at the back of the Duchess that day in 2000, I pull out my CD copy of Work And Non Work, their 1997 singles compilation, and offer it up to be signed in biro. James scrawls his name without comment but Trish seems almost embarrassed, joking that things like this – “pop stardom” – don’t really happen to people from Birmingham. She writes her message in the top left of the inlay in small letters to avoid spoiling the artwork. “To Anna, Love Patricia”. Her humility has stayed with me ever since. Trish died in 2011 after flying back from a tour of Australia during which she contracted swine flu which developed into pneumonia. She was 42.

Whenever I come back to Broadcast – often via the two follow-up albums, 2003’s Haha Sound and 2005’s Tender Buttons, which form a trilogy with The Noise Made By People at the apex – I find myself again staring through the pub door, listening to the upward swoosh of ‘Come On Let’s Go’ as it pulls me away from some place and towards somewhere else, destination bright and hopeful, yet still, after all these years, unknown. I am not alone in loving this perfect little track: it has more than 20 million streams on Spotify. Was it an ode to leaving a fading party before the bitter end? That moment when your friend knows better than you that it really, really is time to depart? Stop looking for answers in everyone’s face, come on… let’s go. And away we travelled; the Duchess closed, the dust settled on our CD towers, we stared at our phones and we forgot to look up. Somehow, though, and for all its vintage loops and echoes of the past, The Noise Made By People still sounds like the well-constructed future – with solid foundations and a good view – that we still hope to find.