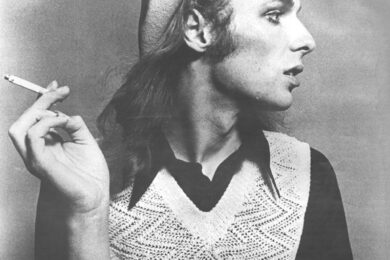

Resplendent is perhaps not a term one would most immediately associate with Blixa Bargeld, given people’s persistent desires to paint him as the dark, lung-splintering overlord of German industrial noise music. However, watching him perform with the Italian composer and ex-Meathead man, Teho Teardo, in Leeds in 2014 he literally sparkled.

His sparkling suit – still black of course – twinkled under the stage lights and Bargeld held court like it was an ‘audience with…’ evening, chatting openly to the room, making playful jokes, subtly dancing and recalling anecdotes from the last time he was in the city with his band, Einstürzende Neubauten, back in 1983, and they acquired a new drill from a neighbouring building site in the darkness of night (a drill which they still use to this day apparently). At one point the alarm went off on Bargeld’s phone to remind him to take some medication. The evening almost felt like an invitation into Bargeld’s private, personal world. Something that the duo’s excellent debut album Still Smiling toyed with too, although of course in true Bargeld fashion, what constitutes a personal or revelatory album in his world is still remarkably cryptic and obtuse, as well as being delightfully wry and playful.

The personal and musical connection Bargeld and Teardo shared was clear and the addition of cello and a string quartet cemented a sense of intimacy, intricacy and profound beauty in the room as Bargeld’s voice floated through it, moving in gloriously fluid rivers of rich baritone, punctuated by the occasional hiss, contained scream or hushed whisper.

Some baseless accusations in recent years have suggested such projects as this, along with some of Neubauten’s later period material, is a softening and a taming of a once seemingly untamable artist. However, such textural explorations and measured restraint have long been a part of Bargeld’s world and you’d need to have ignored a significant chunk of Neubauten’s back catalogue to have not encountered similar excursions in texture, pace and delicacy. Nevertheless, one of the starkest achievements of this collaboration is how deep the foundations of it already feel. Despite only existing for three years, Bargeld and Teardo have already forged a world that feels distinctly of their own creation, operating entirely separately from the large shadows of their many other projects.

The pair released a limited edition EP, Spring, as a follow up to their debut and have now just released their second LP, Nerissimo. The project is a trilingual one in which Bargeld slips deftly between German, English and Italian and the cello-led sonic explorations of the first LP have given place to woodwind on this album, particularly the bass clarinet as the pair continue to expand their palate significantly. Over green tea in Teardo’s studio in Rome the pair discuss the album.

Did the pair of you always plan to make a second record or did the success of the first one trigger the decision?

Teho Teardo: We played so many shows after the first album that we just wanted to do more.

Blixa Bargeld: Yes, we wanted to play more shows so the necessity of this business is that you have to make another record. So this album was simply born out of the wish to play more.

That’s interesting because the last track on your debut album, ‘Defenestrazioni’, explores some of the banalities of life on the road. Do you have a love/hate relationship with touring?

BB: I believe anybody from the lower to the higher rockstar department has a love/hate relationship with the travelling part and the hotel rooms. This is more a fun take on it though when I did ‘Defenestrazioni’. The sitting in the bus and the hotel are not the high points, for sure. Playing is wonderful though, I love it very much.

The album cover is a recreation of the Hans Holbein The Younger painting, ‘The Ambassadors’ (1533). What can you tell us about your relationship to that painting and why you chose to base your cover on it?

BB: I seriously thought about bringing in a painter to do a classical style double portrait but I think it would have been a bit risky. If you don’t like the painting you only have one shot. I then just suddenly clicked and thought ‘The Ambassadors’. On the original floor of the painting it is representative of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, somehow representing the order of the world and I knew this would be difficult for a set builder to do a floor like that, so I said do the floor like a Jackson Pollock as I thought that’s much more representative of our order of the world. He built the skeleton of the set and we built it up with all the objects and things from our personal life and surroundings. We did a lot of tongue in cheek there.

Given you have both worked with so many people over the years and have clearly found something unique between the two of you. What would you say is key to a successful collaboration?

BB: In general a collaboration as duo at its core is a completely different thing to a band. In a band you have to deal with at least three different characters, if not more, and you have chemistry and ego, in both a bad way and a good way. With a duo it is automatically a different working relationship. This is just about me and Teho and we are not involved in any kind of file exchange program, we are working face-to-face, we work together on the material. For example working with Neubauten or the Bad Seeds is a different thing altogether.

TT: We really work together, we like working in the same room. I start making some sketches, some ideas here…

BB: Then he will come to Berlin to Neubauten’s studio and we continue there and then I go back to Rome, we do that four or five times then we arrive somewhere, or hope we will. In the modern situation that the music industry is in, combined with the technical possibilities as they are, it is favouring a particular working process. Which is basically one or two people sitting in front of a monitor or they are doing a file exchange program somehow. The dinosaur of that business is a band, it’s uneconomical and the means of production have changed enormously over the recent decades in the industry.

At times in the 80s I would get a budget from a record company for making the sleeve that was as high as what I would get nowadays for making an album. That’s how different it is.

That’s why you have a lot of electronics and a lot of duos and single artists and remixes because once you get seriously into singing or analogue instruments or strings and you start working in a room or a studio things suddenly explode in cost. That of course then has a feedback on how things get produced and made nowadays. Deliberately I don’t want to swim that way. Working with Neubauten I work in a very very old fashioned way and working with Teho I do the same. I made a record with Alva Noto, ANBB, a beautiful record, fantastic, but a completely different working process and I know that simply due to the fact that I work in a room and I work in a recording studio, it ended up being the most expensive record Raster-Noton ever made.

When you work on something for several years and go back and forth between your respective cities, how do you know when the project is completed?

BB: I write to the music, I don’t write lyrics beforehand. I make notes everyday but i deliberately write to the music. So, once I get to a point where I can’t push that date any further away from me, I start writing. Because for me psychologically it’s a place I don’t want to go. Once I have committed myself to finally writing, I am psychologically eaten away by it. I wake up in the morning with it, I go to sleep with it, I wake up in the middle of the night with it and make notes. My family is suffering and my child is suffering because I am seen to be somewhere else. So I write everything in a short period of time, take the mixes that we have so far and I go, with headphones, to a hotel bar in the morning and start writing until I’m empty. It’s always going on in my head though, it’s like background processing, I really literally will wake up in the middle of the night and find a missing word I was looking for in a line or I’ll come to a solution that something has to be structured one way round instead of another way and of course my wife notices that. It’s not a place that I want to go, so that’s why I push it away all the time. Then once I’m there I’m in there and I can’t move out of it until I’m finished.

It really does take over every aspect of your life, then?

BB: Yes, even if I cook spaghetti I know that it’s still going on in my head. I’m still processing in the background what is to be done in the next line of the song. Then the multilingual aspect as well means I’ll be working with an Italian translator or linguist, who I send ideas and words back and forth with to check with Teho if they work.

Blixa, I read you once coming across some Chinese people singing Italian opera one evening and I wondered if that factored into your decision to learn and sing in Italian on this project?

BB: We had a house in Houhai and in the winter the lake had frozen over. One of the musical academies was around the corner and we decided to walk back from a restaurant across the lake and in the middle of the lake there were three Chinese men practising Italian opera [imitates open arm singing and mimes] with scribbled paper in their hand. My Italian comes from Latin as we were taught Latin in school. I really don’t speak Italian, I speak kitchen italian, I can order in a restaurant but I can’t really speak it, I fake it. I have a few sentences that I can use really well in an answer when I detect what somebody is going to say.

The title of the album, Nerissimo, means “The Blackest” in Italian. It struck me that this could almost act as a metaphor for your work in that a simplistic, surface-level, view may be that it’s ‘dark’ but black is made up of many other colours and shades and ultimately has much more depth to it that than its casual appearance?

TT: I think that would be a little predictable.

BB: Originally the record was called Christian and Mauro, based on our original Christian names. Then looking at the final product and the sleeve it simply would not have worked. The title song I really wanted to sing in Italian and I was sat at the hotel bar and I Googled Italian colour names and I wrote down all the ones I found interesting. I checked them with Teho and he then pointed out nerissimo. That’s good because it doesn’t really mean anything, it’s this superlative for black in Italian but it’s more…an Edgar Allen Poe story would be nerissimo, it has a poetical dimension to it. Describing a work of art is nerissimo.

TT: In Italian you can use it if you’re in a really bad mood you’d say it but it’s only about the mood, and I’m talking about a really bad mood.

BB: I don’t think we’ve made a bad mood record though.

TT: It’s quite a rare word, not many people use it and I find it a very poetical word.

BB: There’s a multitude of colours for me in that record, to me in my mind, it always seems more green than black. I associate it more with the colour of that curtain on the cover.

On you first album, Still Smiling, you covered a Tiger Lilies song, ‘Alone with the Moon’. On your EP you did ‘Crimson & Clover’ and on this album you have covered ‘The Empty Boat’ by the Brazilian musician Caetano Veloso. Where do these choices come from?

BB: I’ve actually come to an end now. On my computer I always had a file full of songs that had a very special place in my heart and that someday I wanted to make my own, to get out of my system. One time on holiday I played Teho several of those songs and one of them was ‘The Empty Boat’, that catched it and that went on the record. Now I have nothing left. Maybe there is one Marlene Dietrich song that I want to do but apart from that I have used them all. I have to come across something that hits me again.

TT: I had never heard ‘Crimson & Clover’ before and Blixa said why don’t we do it, so I went to a record store just around the corner and asked for a copy just to listen to but he pulled out this 7" of the Italian version, ‘Soli Si Muore’…

By Patrick Samson?

Both: Yes!

BB: We came up with that when we were still touring the first record, we hadn’t recorded it as yet and I just thought we needed something like that as a surprise encore. Then it was just a great coincidence that there was an Italian version that seems to be completely forgotten. So many movies have been in touch asking to use it, although of course that doesn’t help us because we have not written it.

TT: After we had been playing that song live I got an email from someone who had seen the show and he said he liked the music very much and had been following us for several years but he said he never expected to hear that song, especially because, he told us, Patrick Samson had had an affair with his mother.

Teho, you said you wanted to move away from writing for cello for this record because you got too comfortable doing it. Is this because you feel comfort can lead to complacency?

TT: I need to feel uncomfortable with a few things and then I start to find my challenge. For instance I am a guitar player, I have been playing it since I was a kid and a few years ago I decided to just play the baritone guitar, which is a completely different beast. I also just bought a lap steel because I wanted to try it. Blixa can play it, I can’t. I really need to have some kind of challenge, I was getting too confident with cello so I thought it could be interesting to work with woodwind on this record, which I never did before.

BB: [whispering with hand over his mouth] Oh no, he’s never played the clarinet.

TT: I played it when I was a little kid. I studied until I was 13.

BB: [whispering with hand over his mouth again] See, just a short period.

TT: I had to study theory and stuff and it was quite tough. Then a friend of mine bought the first Ramones album…

BB: There’s the famous clarinet solo on that album.

TT: I got an electric guitar…

BB: You don’t remember that one guy from the Ramones that played the clarinet? You know, ripped jeans and [mimics someone jumping around with a clarinet]. Maybe that could work actually, maybe someone could do a classical version of ‘Rocket To Russia’ or something.

TT: Plus back then as a teenager if you would go to a party, socially it’s not very…

Cool?

TT: Yes, but it’s interesting because I’ve studied music since then.

BB: I think there is a common point there between me and Teho and that is a certain favour of this aught aspect of a particular instrument and that’s why it’s also very important to be in a studio with microphones etc because the way something is played, I think we both have a favour of the rather unusual way of playing something.

TT: In general I never like to write something that musicians feel comfortable with.

BB: It’s not sadistic just to let you know.

TT: For example, I like writing something for the cello that is meant for the viola. That’s creating some sort of tension in the music I like. Someone I work with is a classically trained musician and sometimes I show him stuff we work on and he looks at it and just says ‘this makes no sense’ and that, for me, is the proof. That’s when you keep going.

BB: The most difficult one on this album was ‘Ulgae’. I listened to it and said, "This is plain weird. I have no idea what is happening here." I couldn’t follow it but that’s where the hotel bar comes in again. Sitting there I decided to write the story. I wrote it step-by-step, what was happening in each part of the song. As you can see it ended up coming out like that, as this microbiological opera [taking place in a petri dish]. The bacteria sing very high and then I put the subtitles on it like they do when they have opera on the radio in a foreign language. I’m now writing ‘The Return Of Ulgae’… be prepared.

Speaking of unconventional recording methods. Teho, I understand you have a fondness for tying musicians in your studio or draping them in a towel or curtain so they play in darkness?

TT: Yes, I do do that because when people play you have this very physical movement, an action. Which is connected to a sound, you get that sound just because of the way they move. It’s like a musical action and so I use tape here and here [touches elbows and wrists] and then they can’t move exactly how they normally do. There are so many interesting things that come out of that, I find it a very prolific way of working because you can get something from them that you normally can’t.

BB: Now you know what the nerissimo really stands for, he’s recording them in a dark room.

TT: I only do it with musicians I have known for a long time, otherwise they just leave the studio immediately.

BB: Dungeon, you mean?

TT: I like it though. There’s a physical movement used to play instruments that we know leads to the same results, so let’s try something different.

Blixa, I understand you consciously took all the reverb off your voice for this recording?

BB: It wasn’t so much a conscious decision, I just asked our engineer to keep taking the effect down until I realised we had nothing left. Then I realised I actually liked that. We have a nice saying in Neubauten which means ‘mercy reverb’. If you’re the singer you ask for a little bit of mercy reverb as it’s what takes the edges off and makes even the bad singer sound a little bit better. Now I’m at the other end and take the reverb off to make it more dynamic and punchy. Some other interviewer said that I don’t sing like I normally do on this record but I actually do, this is my normal way of singing. It’s just part of the natural ageing process. If I listen to my records from 1981 I think, "Wow, I must have been young" but it is partly in registers I can’t even reach any more.

TT: That lack of reverb is creating an interesting sense of intimacy I think. It’s like having a voice in front of your face or in the room.

BB: It’s like the closet mix of the third Velvet Underground album. I think they tried to create something very similar there, this very intimate feeling. This has always been an album that has been very dear to my heart and I have not connected it to this album of ours yet but I just remembered that link with the no reverb.

Teho, you have written a lot of scores and worked in cinema for years. Do you view this project in cinematic terms or ideas at all?

BB: We do actually talk a lot in cinematic terms.

TT: We use cinematic terms to discuss many aspects of our work.

BB: Many people don’t know but I have a cinematic background too; I used to run a cinema. I trained to be a projectionist. In fact, sometimes we even talk about camera angles, so if it would be a tilt or a close up. It’s not necessarily about making the music more cinematic but our use of metaphors is settling a little bit in that territory.

TT: We both have a lot of visual terms to describe music. I find it quite useful.

BB: He’s having lunch with Ennio every now and then, I’m very jealous.

TT: Morricone doesn’t speak in cinematic terms.

BB: Oh?

TT: Never. The first question he asked me was, "Can you write a fuga?" And I was a little intimidated because he has this voice like this [imitates something sounding a little like the cartoon character Roadrunner]. Fuga in Italian means escape and I told him that I came from rock & roll so I have a long history of escaping from several situations and he seemed to like that.

Are you working with him on something?

TT: No, I asked him a while ago if he wanted to play for a couple of days with an old synthesizer that the national radio had in the 60s and 70s as I found the collector who bought them. I said, "Why don’t we do two days in front of this giant wall of synthesizers?" And he said, "No, no." So then I said, "Why don’t we do an album with an orchestra?" And he said, "I don’t think the world needs another record with an orchestra on it." So then I said, "Well how about we do a couple of days recording; two synths, me on one, him on the other but he still said no, so nothing. He’s been very kind and nice to me, tells me things only a father would.

Has he heard this project? Did he like it?

TT: Yes, he did. He likes what I do in general. He also wrote a presentation [liner notes] for one of my records. It was the first time he did anything like that. Even though he’s a very difficult man he’s been very sweet with me.

BB: Yeah, I can’t trump that. I can’t say that I’m having lunch with Hans Zimmer or something but I have the feeling that wouldn’t impress you as much anyhow. Even if I said Hans Zimmer was like a father to me…

What’s unique about this project to you? What do you get out of it that you don’t from other things you work on?

TT: There’s a very tight connection between us, musically and in friendship and it really shines when we record and when we play live. I feel both territories are very connected and when we play live and play shows I’m already thinking about new material. It’s like a cycle that keeps feeding itself. It’s really emotional to me and we are already planning on recording a new EP.

BB: There is another song already completed that didn’t end up on the album because it didn’t fit theme-wise. So that one is delayed for the next record.

So, if this project your priority for the next year or so?

TT: For the next year, for me, yes.

BB: Yes it is. Neubauten are on hiatus so until next year, so I am dedicating my time to this.

Neubauten have a show booked in for early 2017, so are you stepping back into that world then?

BB: We have a show opening up the Hamburg venue, Elbphilharmonie, which is a new scandalous building that has taken ten years longer than it should have done and cost a hundred times more than it should have done. So, yeah, for the opening of that somebody thought it would be a good idea to get a band called collapsing new buildings to play. Ha ha, the joke is going to be expensive.

Nerissimo is out now and Teho Teardo & Blixa Bargeld play their only UK date in London at the Rich Mix on June 2