"It’s worse than ever," lamented Benny Andersson in 1978 during the recording of ABBA’s sixth LP. "We have no idea when we’ll be finished."

"I can tell from the look in Björn’s eyes when he gets home how the day’s work has been," Agnetha Fältskog famously told the press. "Many times [Benny and Björn] have been working for ten hours without coming up with one single note."

In 1978, ABBA were riding the crest of a very big, very lucrative wave: No 1 hit followed No 1 hit, like a string of perfect Scandinavian pop pearls, and multi-platinum albums followed sell-out tours and even a top-grossing movie; ‘Take A Chance On Me’, meanwhile, had just become their seventh UK No 1 hit. ABBA were the Midases of pop. By the end of the year, not only were complimentary ABBA perfumes on sale (Anna by Agnetha for the day, Frida by, well, Frida for the night) but ABBA: The Soap was also commercially available. You could even smell like your pop heroes.

But then… nothing. Most artists, of course, go through peaks and troughs of creativity. There’s nothing quite as satisfying, for instance, as when your favourite artist pulls a late-career gem out of the bag after a period of indifferent endeavour. But what happens when a group experiencing their most extensive commercial success, is at the top of their game artistically, with inspiration seemingly at a premium – yet now feeling the increasing weight of public and critical expectation – suddenly finds the well running alarmingly dry?

ABBA had settled comfortably into the album-a-year cycle expected of mainstream commercial pop acts in the Seventies, and each new entry into their discography built exponentially on the last. Somewhere around early 1976, with the chart-topping success of ‘Mamma Mia’, they began to slough off the one-hit wonder tag that had hung, albatross-like, around their necks since the Eurovision-winning ‘Waterloo’, and became the pop group of their generation. A trove of glistening chart-topping hits followed – the radiant pre-disco of ‘Dancing Queen’ had followed the wistful ‘Fernando’ to the upper echelons, and was followed in turn by the chilly, spectral magnificence of ‘Knowing Me, Knowing You’.

"Novelty" and "kitsch" are two words often erroneously associated with ABBA, and while some of their more homespun stage costumes would suggest otherwise, albums like 1976’s Arrival and 1977’s The Album highlighted ABBA for what they really were – a pair of extraordinary songwriters in keyboardist Benny Andersson and guitarist Björn Ulvaeus, two men with the keenest ear for melody in pop, and two markedly different singers in the soprano clarity of Agnetha Fältskog and alto decadence of Anni-Frid "Frida" Lyngstad, who, together, created harmonies of imagination and invention.

Blessed with a backing band of precise session musicians and a sympathetic engineer in Michael Tretow, their albums increased in sophistication and production values, and by 1978 not only were they the world’s biggest pop group but they were making some of the world’s leading pop music. So why did it go so wrong?

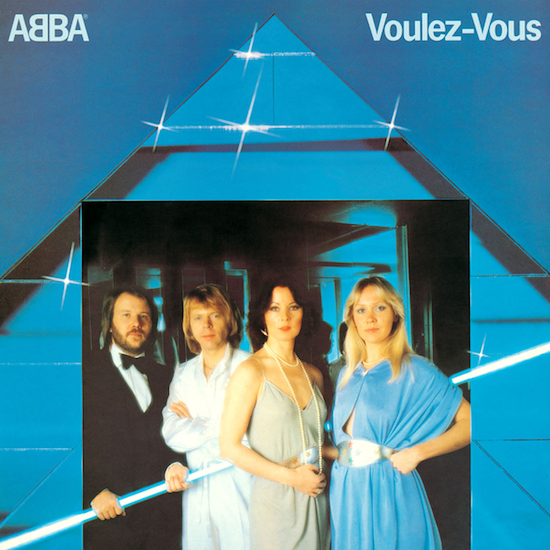

The album that became Voulez-Vous is an album of pulsating tensions – tensions within the group, tensions within the music, tensions between a desire to create and a fundamental lack of inspiration. Beneath the swish, pyramidic icy-blue album sleeve and pumping disco arrangements, it’s an album that pastes a glossy sheen over songs that exhibit a stark dichotomy between vivacious lust and bereft heartbreak, songs that appear to demonstrate a tug-of-war between modern complexity and traditional values; it’s a glittery jumpsuit-wearing Frankenstein’s monster of surgically transplanted parts and filled-in blemishes.

Fundamentally, it’s the album that enabled ABBA to continue to function as a pop group. When, in May 1978, ABBA inaugurated their own music studio, Polar Studios, in a disused cinema in Stockholm, panic was yet to set in. Polar was, at the time, one of the world’s most modern and well-equipped studios: it boasted two 24-track consoles, separate rooms with different acoustics, distinct mixing consoles connected to each musician’s headphones to allow for greater autonomy per artist, and according to Benny, "lots of open spaces and glass so you could have eye contact with all the musicians."

But, despite the open-plan architecture, Polar became, initially at least, a wall built between ABBA and the outside world. What was devised as an opportunity to create in the most comfortable environment possible became a force of constriction, isolation, and stifled creativity. It was a marker of their extraordinary success that they could install such a space, but the early signs were not positive.

It is perhaps ‘Summer Night City’, a song squeezed off the eventual track list like matter from a lanced boil, that best illustrates the problems that beset ABBA during the making of Voulez-Vous. A frenzied burst of manic disco, ‘Summer Night City’ is menacing where ABBA were once unthreatening, relentlessly minor chord where they once fashioned joyful choruses from sorrowful verses, it throbs and keens where they once soothed and soared. The uncharacteristically lusty lyrics, of "lovemaking in the park" and "scattered driftwood on the beach", of the "the strange attraction from that giant dynamo", were worlds away from the breezy simplicity of ‘Take A Chance On Me’. But this, in the summer of 1978, was the only song they had in advanced enough a state to work with.

In the Seventies, especially for a titanic pop act like ABBA, six months between singles was an eternity; a seven-week summer break from recording yielded no substantial new songs and, feeling the pressure from the international markets they had worked so tirelessly to break into, ‘Summer Night City’ was moulded, compressed, and tweaked like a scientific specimen over the course of a series of stressful week-long mixing sessions. Tretow recalled how they "tried every way imaginable to get something from the tape that simply wasn’t there – in fact, there are other mixes that are even more compressed." A moody 45-second intro of strings, piano, and vocals was cut from the final release, and Björn described the finished product as "a really lousy recording overall. The song would have deserved a better treatment."

Finally, accompanied by a memorable video, it was panic-released in September 1978. Reviews were not complimentary. "The calculating Swedes have produced a piece of disco muzak," cried Record Mirror. "By no means as memorable as earlier stuff," said NME. As John Tobler recounted in Abba Gold: The Complete Story, inky Melody Maker got themselves into a lather over supposedly risqué lyrics, and gloated, "It was only a matter of time before they sidled into the Gibb Brothers’ disco penthouse."

In reality, ‘Summer Night City’ has aged well. It certainly does have a foot in the Bee Gees’ disco penthouse, with its disembodied gender-fluid harmonies and off-kilter synths, and, taken in the wider context of the ABBA canon, exhibits a bravery and courage in rejecting most of the things that made them so successful previously. It is decidedly un-ABBA-esque. While not an outright flop, the song failed to scale the heights of previous hits and became their first single to miss the UK Top 3 for three years. As recounted in Jean-Marie Potiez’s Abba: The Book, the misfire of ‘Summer Night City’ and the lack of inspiration all threatened to derail the entire sessions: the few songs already completed were strongly disco-inspired – "the pulse of the Seventies," as described by Björn – but the general public seemed unprepared for a disco-fied version of the group.

Indeed, the lean towards disco music was causing tensions, too, within the songwriting team. "I have to say, I was just a little reluctant to us doing disco songs," said Benny, "simply because everybody else was doing it. My feeling was, ‘Wouldn’t it be more fun to do something that everybody else isn’t doing’?" Björn, meanwhile, developed an acute interest in the sounds pervading the airwaves, from the Bee Gees and Donna Summer to Chic and Moroder. These club-infused flavours found their way into the album largely through the lead guitar work of Janne Schaffer, with Lasse Wellander helping guide more of the traditional material. The proliferation of guitars is one of the hallmarks of Voulez-Vous – where the guitars once added atmospheric melodic hooks, here they were woven into the fabric of the music.

According to Carl Magnus Palm in Bright Lights, Dark Shadows, perhaps the greatest tension during the making of Voulez-Vous was reserved for the disintegrating relationship of Björn and Agnetha after seven years of marriage. The album sessions, already exhausting and abortive, were fraught with miscommunication, rows, and unease. As Benny said, "It was very difficult before Agnetha and Björn separated. They were getting on very badly, it made things very difficult for the rest of us and created a lot of friction."

Conversely, Benny and Frida, amid this interpersonal chaos, married in October 1978 in a low-key ceremony. Not only were marital tensions affecting the group, but they were now a quartet of two distinct, incompatible halves – one blissful, one broken. The energetic sensuality of ‘Summer Night City’ had somewhat destroyed ABBA’s musical image of family-friendly innocence – an image Agnetha described as "embarrassing" in an interview with Swedish newspaper Expressen in 1978, and the divorce, announced to much press fanfare the following January, somewhat destroyed the "happy couples" myth that, in some ways, was key to their mainstream appeal. ABBA were no longer the radiant collective of amiable, committed couples making pure songs about life and love; they were fragmented, disjointed players in a Bergman melodrama making unfamiliar, disconcertingly sexy disco music.

Where the similar personal tensions had fuelled the music of their Anglo-American counterparts Fleetwood Mac – the songs of Rumours pouring out like rivers of bile and beauty – ABBA found themselves at stumbling blocks every step of the way. A crisis meeting was held with manager Stig Anderson and, ultimately, they decided to carry on as a group.

But still, progress was slow. By the time of ABBA’s successful Japanese sojourn in November 1978 (prompting 800,000 Japanese sales within a month), it became clear that a Christmas LP release was way out of reach and spring 1979 was eyed, perhaps optimistically at this point, as the target. The few songs worked on in late 1978 showcase the level of uncertainty, indecision, and misdirection plaguing ABBA at the time, but there’s no denying that some of the old magic was returning. Perhaps Agnetha and Björn’s decision to split had unblocked a creative synapse – the bewitching ‘Angeleyes’, despite dismissals from both Benny and Björn, is a delicious slice of Sixties-style girl group pop. Shimmering synths and percolating guitars provide the bed for some of ABBA’s most unusual and octave-hopping harmonies; indeed, the vocal sessions were often a source of conflict – Frida described how Benny and Björn would push the vocals "almost beyond the limit of our voice ranges." Björn recalled how, for Benny, "it was almost an obsession – ‘Do you think you could sing that an octave higher?’ was a standing request from him when we were recording the harmony vocals." This can be heard in ‘Angeleyes’, where, Agnetha notes, "it makes for a quite special sound when my vocal part was an octave higher than Frida’s."

’Angeleyes’, like the menace of ‘Tiger’ from Arrival, takes the seed of Laura Nyro’s bad-boy warning in ‘Eli’s Comin” and swaps out the R&B/soul noir for blue-eyed Wall of Sound Spector pop. Recorded around the same time, the dolorous disco of ‘If It Wasn’t For The Nights’ resituates ABBA’s predilection for melancholy yearning (notice the motif of "staring at the wall" from ‘Ring Ring’ recurring here) to the modish glamour of the clubs; a sumptuous string arrangement wraps around funk guitars and buried horns, while the strident yet resigned chorus, sung with abandon, is the Voulez-Vous version of the downbeat style perfected on songs like ‘S.O.S.’ and ‘Knowing Me, Knowing You’ – where minor chord verses bloom into majestic choruses and where beauty emerges from loneliness and sadness. It is almost like a forebear of Robyn’s brand of sad electropop. Lyrically, it details Björn’s despair in the death throes of his marriage – "those lyrics were written during a period when I was feeling really depressed," he said. "I was down as hell". This hit-that-never-was was initially slated as the album’s lead single, and was even premiered on Japanese TV some six months before the album release, but in time was shelved in favour of a markedly different song.

‘Chiquitita,’ which developed in the final weeks of 1978, is a clear evocation of the creative indecision that marks Voulez-Vous. ‘If It Wasn’t For The Nights’ and especially ‘Summer Night City’ had been so boldly different for ABBA that <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5_GwjWux7Hw" target="out"">’Chiquitita’, a classic ballad in the mould of ‘Fernando’, smacks of cold feet about their possible new direction. There’s no way you can deny that it’s a definitive, truly beautiful ABBA song, with its soaring harmony vocals and warm melody, those crunchy mid-verse piano chords and rollicking coda betraying Benny’s classical roots. But taken within the context of the album, where ABBA seemed to be reaching for a new kind of modernity, it sounds comparatively regressive. There was continued tension between a hunger to move forward and a loyalty to their traditions, between Björn’s desire for disco dalliances and Benny’s reluctance to follow the pack. "It’s hard to try and achieve something that is outside of your own tradition," said Benny. "It’s so European to be ‘square.’" In short, there was a lack of commitment and an absence of clear vision.

By early 1979, with less than a side in the can, they decamped to the Bahamas in the pursuit of more creative inspiration and reluctantly accepted that outside stimulation might have been necessary to move this strange, uncooperative beast of an album along. ’Voulez-Vous’ is the song that finally propelled the album sessions. In February 1979, ABBA took the decision to record at Miami’s Criteria Studios, where the Bee Gees had created much of their music, and they made use of an expert disco backing band in Foxy, who were fresh off a US R&B No 1 hit with ‘Get Off’, and a producer/engineer in Tom Dowd, who had worked on music by Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, and Dusty Springfield, and had worked on ‘Layla’, ‘I Shot the Sheriff’, ‘Sailing’, and ‘The First Cut Is The Deepest’.

’Voulez-Vous’, then, is the sound of American R&B and funk done the Scandinavian way; it is a mysterious, elegant morsel of disco, burbling with sexual tension and dark majesty. "What I had in mind before I even had the title was a kind of nightclub scene, with a certain amount of sexual tension and eyes looking at each other," said Björn, and the ‘Lady Marmalade’-referencing title accentuates the taut eroticism.

It’s a Chic-esque tapestry of guitars, trombones, and tenor saxes; the vocals are aloof and enigmatic, and the production is modern and sleek. Where the disco of ‘Summer Night City’ had a layer of eccentric foreboding, and the disco of ‘If It Wasn’t For The Nights’ stiffened against the European melodies of classic ABBA, ‘Voulez-Vous’ took this contemporary inspiration to the nth degree. Working outside of their Stockholm enclave had proved a boon to their creativity in an unimaginable way. Benny and Björn deserve kudos here for recognising that their working methods weren’t working, and this is a prime example of a top pop act swallowing its pride and trying anything to get the wheels moving again. The desire to create was ultimately stronger than the lack of creativity, and if it meant hunting it down in unfamiliar locations, so be it.

Writing in the Bahamas and recording in Miami, working in different environs and with new people, had solidified a resolve that brought ABBA back to Stockholm with fresh impetus. Within two months, the rest of the material emerged in a tidal wave like the ABBA of old. But that isn’t to say that it was all of a piece – indeed, the general chaos surrounding the making of Voulez-Vous translated into chaotic music, music that was at odds sometimes even within the same song, let alone the same album. But finally, inspiration was there. The sonic palette of the record became an edgy, curious mix of disco beats, funk guitars, string arrangements, and traditional pop. The songs are a grab-bag of styles and sounds that make strange bedfellows yet somehow, texturally, complement each other.

‘Does Your Mother Know’ is a Rod Stewart-inspired glam curio that was laced with disco zest during the sessions, an anomalous Björn lead vocal atop an underrated and expert dynamic mix; ‘As Good As New’ welds a buttoned-up baroque string arrangement by Rutger Gunnarsson to Janne Schaffer’s disco funk guitar, the polarities tensing along a propulsive disco beat; the schmaltzy peace anthem ‘I Have a Dream’ (working title: ‘Take Me In Your Armpit’), like ‘Chiquitita’, is more ‘ABBA of yore’, a simple, syrupy schlager with accompaniment from the International School of Stockholm Choir – like a cosy mulled wine at a Christmas market; the Bahamas-birthed ‘Kisses Of Fire’, meanwhile, bristles with sexual energy ("I’m at the point of no returning" was not your typical ABBA lyric), a dreamy introduction segueing into a power-pop chorus and a peculiar synth-accented midsection. There are, of course, perverse shades of Fleetwood Mac in Björn enlisting Agnetha to sing his lyrics about a sparkling new love affair ("I’ve had my share of love affairs, but they were nothing compared to this.")

And what of perhaps the two weirdest songs in the entire ABBA canon? The deconstructed disco of ‘The King Has Lost His Crown’ merges an unorthodox, jazzy verse replete with electric piano that wouldn’t be out of place on a mid-Seventies Steely Dan record with an angular, camp chorus that is surely one of ABBA’s most unusual. ‘Lovers (Live A Little Longer)’, meanwhile, crystallises ABBA’s newfound abundant sexuality, an offbeat funk experiment with a bewildering chorus unlike anything else in their catalogue. Descending chords, strings, and synths converge to create something oddly alluring but distinctly jarring.

For all its disjointedness, the album boasts many classic catalogue moments – who can resist that moment in the made-for-12" mix on ‘Voulez-Vous’ where the arrangement hollows out and the "a-ha"s punctuate that perfect rubbery bassline; or the first chorus of ‘As Good As New’, which thrums along with a string and rhythm section like a proto-‘Hounds Of Love’; even the elongated "believe" in ‘I Have A Dream’ is pure ABBA-esque ear candy. Then what about the manipulated vocaliser in ‘The King Has Lost His Crown’ that builds into a climactic final chorus, or the skittering synth pulses in the midsection of ‘Kisses Of Fire’ that preface the camp drama of "losing you!"; Agnetha’s cry of "I’m exploding!" on ‘Lovers’; or the dynamic "take it easy" post-chorus of ‘Does Your Mother Know’, borrowed from the discarded ‘Dream World’. These moments leap out like glittering strobe lights at Alexandra’s, the Stockholm club where the neon-hued album cover was shot. (Although in Ingmarie Halling and Carl Magnus Palm’s ABBA: The Backstage Story it is revealed that the photo session was regarded a "total fiasco from start to finish," at least according to photographer Ola Lager – it wouldn’t be Voulez-Vous without some pandemonium, would it?)

Voulez-Vous, then, is a pivotal point in the ABBA oeuvre. It marks something of a tipping point between their blockbuster commercial heyday and the monolithic artistic triumphs that followed at the dawn of the Eighties. Simply put, it is arguably their most important record in a) enabling them to continue as a group and b) allowing the production of the albums that followed. It’s the sound of a group torn between the elements – torn between following the trends of the day and setting their own agenda, between the traditional European music that had been their bread and butter and the quest for modernity, between shutting out the rest of the world, creating in isolation, and seeking inspiration outside of their comfort zone – literally. By latching onto disco trends, it was both firmly of its time and incredibly out of place with what else was coming out of the contemporary music scene of the late Seventies; but it is telling that Sid Vicious, Pete Townshend, and Elvis Costello all professed a love for ABBA.

While perhaps not their best work, Voulez-Vous was crucial in laying the foundations for arguably ABBA’s two greatest records, 1980’s Super Trouper and 1981’s The Visitors, austere synth-pop classics with a depth of emotion that influenced an entire generation. On those records, that insular cottage industry of the Polar Studios was completely fundamental to their success. On Voulez-Vous, at a time of all-encompassing pressures, it was uncomfortable, punishing, and stifling. And that’s why it’s so interesting – it says a lot about what happens when chartbusting groups hit artistic walls. It says a lot about the fight to find inspiration, a lot about how the love of music and drive for creativity can override the destruction of personal relationships, a lot about what it means for artists who must struggle through difficult moments, through creative sludge, to achieve their greatest triumphs. There’s both an angular stiffness and a footloose abandon about the music, which is probably no surprise considering its tense and troublesome gestation. It’s an example to follow for artists who find themselves at what appear to be consistent dead-ends. Forty years on, Voulez-Vous shows that sometimes dead-ends can become crossroads, if you keep plugging away.