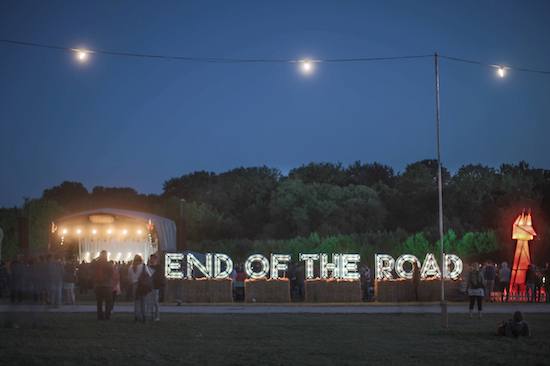

Photo by Richard Gray

End Of The Road is just that for the festival season: one last hurrah to signal its conclusion, balanced precariously on the border between a bluntness and mysticism, Wiltshere and Dorset, summer and winter. Cold enough to shake off those whose festival decision-making is a straight shoot-out with a package holiday and late enough in the day for artists, traders, organisers, punters to have surpassed that third weekend of August insanity. It is a tug of war between peacocks serenading you with squawks, sending notes via a foot-peddled postal service and utter picking mushrooms in the woods, gurning in a hall of mirrors weirdness. It’s these conditions that create opportunities for randomness, brilliance, and calamity, making End Of The Road a milieu for the memorable.

This is like a tenth birthday party

This year End Of The Road has thrown its own tenth birthday party. They’ve spent weeks crafting oversized paper-mache animals, bringing an organic wine company into their home and, being the warm-spirited kid in the neighbourhood, they’ve invited the foul smelling deadbeats from out of town around to play.

Much like a children’s pre-teen birthday party, it is soundtracked by a birthday cake of sweetly out-of-key melody. 2015 will surely become associated with the rise of low-slung, out-of-tune guitar, slack jaw vocals, and the migration of listeners dressed as Philadelphia’s McPoyles. Despite its familiarity, there’s a breadth to the writing of this movement that makes it more than sun cream slapped on an Archers Of Loaf revival, however. It’s nice to have the aforementioned characteristics stomped into your psyche by Madrid quartet Hinds, who are a shotgun of illogical, disjointed Velvet Underground-inspired pop. They’re like a cold breeze in prickly heat: inexplicably pleasurable.

Add Welsh melodic-contortionist H Hawkline to the list, actually. His pieces intriguingly exist on a tangent, propping up a strange culture of lyrics bereft of any real world sense. The audience seem to garner more from the elongated sections of chitchat between songs in Welsh than the obscurity of the lyrics themselves. It is the angular, nonsensical structuring beyond the nonplussed charm that interest.

That brings us to the lost uncle in the corner, the guest of honour, Sufjan Stevens: showing family holiday projections and exercising demons of loss. This freshman UK festival appearance for the American falls in support of Carrie And Lowell, an album about the recent loss of his mother. It is a set, however, that doesn’t really follow the same conceptual ambition as the record it’s devoted to. ‘Casimir Pulaski Day’, ‘Futile Devices’, ‘Concerning The UFO Sighting Near Highland, Illinois’: we’re walked through pieces from the extensive melodrama of his back catalogue, albeit along the folksier, storytelling path. Largely absent from the set, Stevens’ most remarkable live show and record The Age Of Adz is the elephant in the room, casting a shadow that manipulates the presence of cuts from Illinois and Michigan. The vertebrae-throttling subs specific to that album are reserved for the most delicate moments of newer pieces like ‘Fourth Of July’. A rush of songs from his new album kindles vociferous flames of physicality and imagination. The less he’s concerned with the attention of the crowd, the more compelling the show becomes, plunging us into uncomfortable, worrying and throttling sparseness.

Shortly before launching into a choice cut from his back catalogue, ‘Seven Swans’, Sufjan dedicates the song to the story of his sister "Megan, who changed her name to Liberty, and is thinking of changing it back to Megan." Beginning with a modest voice, rising as a phoenix, and eventually trying to relate to the human condition he abandoned: perhaps Sufjan’s focus on a trajectory of becoming Sufjan again is really at the nucleus of tonight.

Alternative programming

You’ll find the finest, most remarkable qualities of End Of The Road beyond The Woods, Garden Stage, Big Top, and in its delicate cubbyholes. From the comical juxtaposition of Sleaford Mods cramped onto a twee library stage satirising the state of the country, the intensity of midnight Scrabble to the subtleties of an instant (and instantly forgettable) demo booth, befitting of today’s industry. It is in the depth of its woods that the festival’s uniqueness really manifests. Curator Will Hodgkinson’s shrewd, concept-a-day work in the cinema is crowned by the back-to-back screening of Sightseers coupled with a Q&A with its director Ben Wheatley. The film is set in some of the Midlands’ most deprived areas but refrains from painting the place as a backward, cheap, grinding vehicle for comedy as it so many films often do. Not-at-all patronising and somewhat refreshing, it offers the first positive portrayal of the region since the breakdown of its Heavy Rock factory in the 70s.

Some distance through the trees, nestled in an amphitheatre shaped bowl is a pulpit from which stand-up be proclaimed. A medium that is so often used to being cramped into basements in cities or sandwiched between circus acts and Zumba classes at festivals, Comedy is given a healthy platform at End Of The Road. Organisers hand the reins of organisation to Sarah Bennetto for this year and it proves to be a masterstroke. A lively participant on the alternative circuit, she has constructed a roster refreshingly reflective of the state of British Comedy in a climate where the scene is increasingly obsolete.

Bugle Podcast co-presenter Andy Zaltzman brings his Satirist For Hire show on Friday afternoon. Sharp and spontaneous, it is fuelled primarily by requests from a festival audience. Dominating the stage with obscene and poignant social commentary, his verbose tangents transport this timberland into the avant-garde of the London club scene. It is, however, the two-pronged appearance of stalwart Robin Ince that manages to offer some of the festival’s uttermost, dynamic comedic moments. His late-night ‘Dirty Book Club’ set is constructed of chosen passages read by choice comics from obscure and dated romantic novels. These blank-faced passions bleed into his hour the following day. We don’t know whether it’s his time spent in the stratosphere of Brian Cox, the birth of his child or the knowledge he plans to bow out from stand-up comedy soon, but this warped, edifying material comes from a man set to finish at his best.

Judging from the cute, dynamic scheduling and kindred respect it shows for the medium, End of the Road may well become a crucial heartbeat for the faltering art of British Alternative Comedy.

End Of The Road is built on an ancient spider burial ground

Awaking from the first night with around fifteen money spiders hanging from the ceiling of your tent is a shock; pulling a further three out of my hair becomes daily routine. Finding out that every other one of the 11,000 on site is undergoing the same daily ritual, you realise the severity of the dark spider spirits that we’re dealing with. Perhaps it’s the climax of cultural spider appropriation brought on by the festival’s liberal use of the hammock? One can’t possibly guess, but it’s time to start worrying.

EOTR knows how to throw a party without inviting anybody

Most of the medium-sized, alternative music festivals have their merits, but a penchant for concealed, unannounced shows belongs to the EOTR. The weekend isn’t a conveyer belt of opportunities for musicians to rock up with their varnished guitars and pose for a few shots but rather has few intriguing opportunities. There’s enjoyment to be found in the off-kilter modal interchange of Marika Hackman, or the impromptu collaboration of Rozi Plain and This Is The Kit, however it is a rare acoustic show from East India Youth that is truly remarkable. Still reeling from the raw physicality and blurred sketches from a familiar electronic set the previous night, stumbling on this is an achingly shy reflection. William Doyle plays through ‘Carousel’ and ‘Don’t Look Backwards’ on a piano buried deep in the woods. It sounds out a battle between an archaic education and his progressive leanings: tension is evident in both artist and audience.

It’s not all wildflowers, birdsong and late summer’s ambience though: Fat White Family are ready to pull out the daisies and start shitting on the soil over on the Tipi Stage. There’s a smattering of after hours shows that leak into the early hours of the morning over the weekend, honourable mentions for Meilyr Jones and unhinged Ex Hex, but it is the Saturday 2am secret slot of FWF that sets the cold air alight. They’re the kind of band you walk away from watching feeling like you’ve both simultaneously had years sliced-off and stapled back onto your life. It is the seizure-inducing madness that has become expected from the South London group but, if at all possible, the group manage to find another level of vibrancy to shunt at the crowd within the new material. By the sounds of it this is a group who, if they’re to achieve their full potential, won’t ever be shirked onto bigger stages but will be locked away and left to malform on top of one another in this exact type of environment.

Just too Quiet for us?

Waiting eagerly for both elbows to the ribs and aural invasion from the bombastic trio METZ on Friday evening, I stand front centre, two back from the rail and insert my earplugs. The trio emerge from the back, jack up their instruments in and start gesturing from inside a glass box. After removing my plugs, I realise I can actually hear the groans of jumping, sweaty people over jagged guitars and pummelled cymbals. I find myself leaning in closer like a grandmother to her grandson throughout, trying to tune into the band’s monitor mix on stage. The group tear through an impressive performance but like a number of raucous acts interspersed across the weekend, their set is constantly undermined by the foible of repressed sound. Though not exclusively, it’s a problem that faces the Big Top Tent, with the likes of Ex Hex, Girlpool, Happyness faltering in the day and even Sleaford Mods to a certain extent in the night. The most baffling example of the weekend is for My Morning Jacket on the main stage, however. A loud group who routinely headline Bonnaroo, Lollapalooza and some of the largest festivals worldwide is sent to warm a crowd anticipating Sufjan Stevens. It’s a tantalising one-two in theory, but in reality is treated more like teenager’s set at the High School Prom before Fred Zeppelin arrives. Singer Jim James’ vocals are inaudible – not squeezed out due to pressure from other sound – but just not present. Stood in the front row, I’m sure I diagnose a guy coughing five rows back with some Vick’s VapoRub during the climactic ‘Touch Me I’m Going To Scream P2’. The experience is made more exasperating when Sufjan emerges and the sound is three-dimensional, perfect.

As somebody who has recently invested in earplugs and whose friends are dropping like flies to tinnitus, I’m well aware of the realities when it comes to volume at shows, but there’s a line in which you just shouldn’t cross duck below. It’s detrimental to the music and patronising to the audience, and unfortunately it occurs over the weekend.

The Garden Stage and one last hurrah

One conversation will have you exhausting the superlatives about the Victorian quintessence and wonderment of The Garden Stage. It is a Garden of Eden of post-Empire oriental treats running into a canopy. Security lounge like lions in front of the stage, allowing the crowd to – in the case of Ought – spin, dive and exist in a reality with no necessity for them. The Ottawa-based quartet showers the crowd throughout rangy, lengthened instrumentals with their aphotic, solemn rhetoric. They’re unusually able to bind the frustrated foils of destitution with rites of passage, and they still seem almost embarrassed at the response this attracts amongst guilt-ridden children of imperialism. Bobbing through "a few from the greatest hits" – the unexpectedly success that was ‘Today More Than Any Other Day’ – like a Byrnian caricature, vocalist Tim Darcy introduces pieces from their forthcoming release, ‘Sun Coming Down’. Less playful, more antisocial and insular, the group seem to be on the cusp of rare sophomore effort that rejects the lure of their debut and instead ventures deeper into the ground.

The intimacy of this large, open air space is almost paradoxical at times. Though there’s a charm to the layered density of Liverpudlian trio, Stealing Sheep, it rather lends itself to scarcity and silence in performances. In an almost Cagian manner, Low flamboyantly paint with dead air, stepping back for the environment to dictate the experience from there. Withholding harmony from arrangements and tailoring tender percussion, it leaves a ghost over the stage for the weekend that can only be quelled by a maestro like Howe Gelb of Giant Sand.

Like the festival itself, Giant Sand are celebrating an important birthday this weekend, though you wouldn’t know it. Despite it being the group’s thirty-year anniversary, he rejects sentimentality on both counts, sliding into "unrehearsed" and new material. Though not garnering the same attention as the Main Stage headliner War on Drugs – a sound better suited to a neglected cassette inside a security guard’s glove compartment – Gelb stands somewhat as the honest depiction of the self-sacrificial, work-focused artist that so many claim to be. If you try picturing it without braces or scuffs on its knees, you can see a silvering End Of The Road festival in two decades time doing the same. Existing head and shoulders above the white noise, still making decisions honest to its own ambitions.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/18746-things-learned-at-end-of-the-road-festival-review” data-width="550">