"Sound morsels and smoke drifts through neon and sky;

set back from that blurred life and its cellular air,

is the bar world, dark soul-holes, the modern plague lairs

where the stalk eyed sniff lines through quick powder stare

and booze children laugh as one culture of volume.

Orange light marks the floor through squares of stained glass

and religious, pale, soft, nudges time through the room.

Rick Holland – ‘Monument’

By rights Culture Of Volume – William Doyle’s second album as East India Youth which is released on XL this month – shouldn’t work. It should be something akin to a mad man’s breakfast. It is a rattlebag over-stuffed with ideas. It skips rapidly from one musical style to the next like a stone skimming across the top of a frozen pond. It switches emotional gear often and mercilessly.

But despite all of this it is a perfect aesthetic whole; these juxtapositions and contradictions are the dynamo that power it; it is a masterpiece of modern electronic pop music, facing forwards while standing on the rubble of much that has come before it.

Doyle, a 24-year-old musician from the British coastal town of Bournemouth who now lives in London, embraced the idea of crushing conflicting ideas, themes, styles and emotions together in order to make the album: “One of the things I tried with this album was to attempt to combine things that wouldn’t usually go together. The whole vibe of the album is certainly trying to force errors by making unlikely connections and seeing what happens.”

The two years of intense effort that has gone into the album (not to mention the mixing skills of British Sea Power and These New Puritans producer Graham Sutton) has transformed these unusual juxtapositions into its core strength; sequenced, as it is, to create a tangible emotional and textural narrative, rather than a confusion of ideas. The album opens and closes with austere, Bowie and Eno referencing synthesizer-based Krautrock.

There is a glistening Pet Shop Boys synth pop monster in ‘Beaming White’, while ‘Turn Away’ is reminiscent of Underworld at their most torrid and sensual. ‘Entirety’ forms a colossally high peak of intense industrial techno, off which the listener must plunge into the beautiful balefulness of ‘Carousel’, the album’s cathedral-like centrepiece which sounds like Scott Walker making a basilica of dub out of the wreckage of synth pop. If there is a more emotionally affecting track released this year I will eat my maudlin hat. (But Hell, if there is a better album released this year, I will eat my hat and your hat and then get stuck into all of the other hats that exist for desert.)

The track ‘End Result’ is one of several examples of the album deploying a steel fist encased in a velvet glove, its wide screen, dark pop sensibility initially distracting the listener from its ultimately fatalistic theme about the transience and unplannability of life. But the song also deals with the unpredictability of the artistic muse. Doyle says: “It’s about the sacrifices that people make to make the art that they make. It’s about how they’re totally at the mercy of how their creativity decides it is going to be on a particular day or a particular month or a particular year and how much that can hamper what they’re trying to create. But you don’t trade that – you wouldn’t trade it for anything.”

East India Youth has hardly been what you’d call quiet in its short existence. The Hostel EP was released on the Quietus Phonographic Corporation [tQPC] in March 2013 followed by the Mercury Prize nominated debut Total Strife Forever released on Stolen Recordings, in January 2014. But with Culture Of Volume Doyle has, commendably, set his sights even higher, in several respects.

I interviewed him over a very pleasant Turkish meal in Hackney, this February.

When did you start thinking about Culture Of Volume?

William Doyle: Pretty soon after I gave you the demo CD in August, 2012, was when I first started thinking about this album. I’d just finished the final mix on Total Strife Forever. I didn’t know what I was going to do with it, I didn’t know we would be doing anything with the Quietus yet. I was just riding a bit of wave. I felt like I’d achieved something. I started to feel quite positive and energetic. More so than when I was making Total Strife Forever which was the totally opposite feeling. I felt, “I can capture this feeling now. I’m going to be productive.” I was living in East India in the Docklands then, and the first track I created was the first track on the album, ‘The Juddering’. The second thing I created was the last track, ‘Montage Resolution’, which was still in 2012. So I had the bookends for the record and I knew straight away that’s how I wanted the album to start and end.

For me, ‘The Juddering’ is the clearest connection to Total Strife Forever.

WD: Yeah, there are a lot of similar sounds and effects to that record. I guess it was so soon after I’d finished that record. I still had ideas about making connections in similar ways. But I think that’s good. I wanted the start of this record to be a bridge back to the last record. I didn’t want it to be a case of throwing out the rule book and starting again. I wanted it to be a total progression.

It’s not your Young Americans.

WD: No, absolutely. I mean what was that – Bowie’s ninth album? So I wanted there to be some lines; some trajectory.

What was your initial idea for what you wanted the album to be like?

WD: Well, my initial idea for what I wanted it to be like was not what it’s turned out to be whatsoever. Because when I started making the first album in 2010, what I thought East India Youth was going to be was a more underground, left of centre, niche thing. I don’t know why I thought that but that’s how I saw it. I guess because I’d been playing in indie bands trying to – for want of a better word – hit the big time for ages, I knew I wasn’t interested in that any more. So because I disregarded that idea of trying to get big that’s what made Total Strife Forever come together. And starting with ‘The Juddering’ I initially thought it was going to keep on going down that instrumental route but since we did the Hostel EP with the Quietus in 2013 and then we released Total Strife Forever commercially with Stolen in 2014, something happened. I think it was performing live that made me realise that I wanted to be more of a front person; more of a pop star. I thought it would be good to take all of my influences from underground electronic music and all of the instrumental music I was listening to and make something a bit more mainstream but with those clear influences. But initially I thought this album was going to be was something more difficult than Total Strife Forever but what’s actually come out of it is a much more mainstream album. It’s not without its challenging moments but there are more songs on it. It’s much more melodic. There are more consciously pop moments on it. And after working on it for almost a year, that’s when I realised I wanted it to be my pop record.

The first lyrics you hear on the record are, “The end result is not what was in mind”, in a song that has numerous interpretations – one of them fairly dark. Is it coincidence that the end result you initially had in mind for Culture Of Volume is not what you initially had planned?

WD: Yeah, that is a coincidence. I only really considered that in that last couple of days. The lyrics I polished off quite late in the day – as I did with all the songs. But the lyric about “the end result” had always been part of the song since I wrote it back in 2010. Some people might find this song pretty dark and fatalistic but I find this song really funny. I guess it’s a weird way to show people your sense of humour – it is a very morbid song. I’m all about making albums into a journey and I know that some people bemoan the lack of sequencing in modern albums because listeners tend to cherry pick these days – and of course, people can do what they want – but I still make albums and I still make them to be heard as albums. I’m big on the idea of it being a journey and a journey that starts from quite a dark place. After all the first words on the record are: “The end”. I do find it funny. But apart from Carousel, I find this song the most emotionally intense on the record. ‘The End Result’ is about the sacrifice people make to do what it is they do. It’s not necessarily about me – it’s about the sacrifices that people make to create what they create, to make the art that they make, to do what they do. And you’re totally at the mercy of how your creativity decides it is going to be on a particular day or a particular month or a particular year or a particular part of your life and how much that can get in the way of everything else. But you don’t trade that. You wouldn’t trade that at all.

Was there anything in particular that sparked off those lyrics?

WD: Yeah, it can seem like a bit of a cliche but I got to the end of a relationship and I found it really hard in that time period to make music when I was living with this person in such close quarters. Maybe it was a psychological thing but when the relationship ended, the floodgates opened and everything started to roll out again. Even though I had a good time during the relationship I enjoyed it, I was afraid the whole time that this was what had been going on – I didn’t get much work done during that period. Generally I think my relationships with people suffer because you have to spend a certain amount of time making music. It’s weird, even though you know that you don’t think about changing your creativity for a second. You just think, “A lot of my personal relationships are going to suffer because of what I’m doing.” And you just get on with it. I felt in a way it just sums up that period in my life.

’The End Result’ is only the first of several what can only be described as epic, widescreen tracks. Is it a balancing act for you? Do you have an innate sense for when you’re gilding the lily or just going to far sonically speaking?

WD: I remember saying when we wrapped this album, “I’m going to have to dial it back next time or I’m going to end up sounding like Muse or something.” I think it’s because I make music on my own in my bedroom and I have done for ten years now. And when you’re in that situation you can either make music that sounds like it was made in your bedroom or you can try and make something transportative thing that totally sends the listener somewhere else entirely. I always wanted to make quite sophisticated music using very unsophisticated means.

So to what extent was this album made in the same way as Total Strife Forever – in your bedroom?

WD: Yeah, 80% of it was. I did the vocals in a studio and I worked with an engineer this time so all I had to worry about was singing and not about pressing record and where the microphone was and stuff like that. I used to feel that you can lose a great deal of the emotional impact of the vocal take if all you are doing is worrying about the positioning of the mic. I know people who spend hours hanging towels up and putting the microphone in a wardrobe because they’re more worried about the reflections of the soundwaves than they are in the emotional impact of the vocal take and the emotion and energy you get from the take.

I also had a friend of mine, Hannah Peel record some strings for me. There are a lot of string sounds on the album – acoustic ones – but I wanted to layer them up to give them some depth. She is on ‘End Result’, ‘Carousel’ and ‘Manner Of Words’. And those strings were recorded in August in 2014, in Memetune studios in Hoxton which is really close to where I live in Bethnal Green. She recorded one of my songs, ‘Heaven, How Long’ for Musicbox and since then we’ve made a couple of tracks together. So I said, “I really want some strings on the record but I don’t have much money.” And she said that it was ok, that she could record as a quartet just by layering herself up.

You’ve signed to XL – I’m presuming there was more of a budget for recording Culture Of Volume, so was there any temptation to get in a drummer or to get in session musicians in – Pino Paladino on fretless bass and a gospel choir?

WD: There was no temptation at all. Because everything’s been going really well non-stop since I started this project in 2012. It’s like Jenga. You remove one piece and then try another piece back in, it might collapse the entire thing. So bringing in another musician wasn’t what I wanted to do. That I actually felt comfortable enough to get Hannah in to do her thing was pretty amazing on its own really.

Has working with Hannah given you any ideas about working with any other artists in the future?

WD: I’ve thought about this quite a lot. I think there’s a lot of expectation involved with me collaborating with other musicians. And I think I got carried away with that idea for a bit but then I stopped and took a step back to look at my working process. ‘The End Result’, for example, took two years to make. I’m not someone who’s going to go into the studio with someone for the afternoon and bang out a pop smash. As much as I’d love to be able to do that – it’s just not how I work. I have such a solitary way of working at the moment that I don’t really know how to integrate it with other people. So not really. Everyone always collaborates with everyone nowadays. Everyone is always going on about how they want to collaborate with X, Y and Z but I don’t know. I’d only like to collaborate with someone if I already had a personal relationship with them.

So were you just caught up in the excitement of the Mercury Prize when the story about you collaborating with FKA Twigs broke?

WD: I never said any of that though. It’s the only time I’ve ever been interviewed were it felt like I was dealing with a hack. I knew [the journalist] was trying to get a scoop out of me – I could sense it from a mile off. He asked me what my favourite record was off the list and out of all of the albums, the FKA Twigs record was easily the favourite. And he interviewed her directly after me and just sort of posed the question to her. She obviously hadn’t heard my record! I think she probably just said yes because she didn’t want to seem nasty I guess.

This feels like an album dealing with heightened states of experience.

WD: All of the tracks are kind of about separate things. I think that my life changed so much over the period of time that the record was done. The last record was me trying to beat some life out of the way I felt and ultimately dealing with it. This one was like… ‘Woah!’ It was like, ‘I need to be able to contain all of this stuff.’ It was like opening up a doorway and there being blinding light inside but to not be overwhelmed by this blinding light. So when it started to happen with Culture Of Volume, it was more a case of how will I contain all of this energy. So every moment on this record is the brain more stimulated for whatever reason, the general excitement of the time and the pace of my life when I was recording it.

Were you keenly aware of the pop potential of the record when you were making it?

WD: When I was comfortable enough letting myself make the record that way, yes. That was a big deal. I didn’t feel comfortable for a long time with this idea or if the record could go down that route or even if it should go down that route. But I ended up realising that this is how I see myself now. And if I don’t do it now, I’ll never do it ever again. All my pop star ambitions exist right now in this space.

The first time you performed one of these songs – ‘Carousel’ – was at your headline Heaven show at the end of last year. Can you tell me about that.

WD: It was quite a big gesture, because I’d been stood behind the table for quite a while, two years and that’s quite an electronic musician stance. And that was a persona I was happy to adopt then but this new persona requires me to be a bit more flamboyant and a bit more energetic I think and just the simple gesture of walking out from behind the table and just standing there and singing and not even manipulating the sound or anything. Big pop stars get to sing over backing tracks… why can’t I do it as well?!

On Beaming White there is a slight influence of trance in the production which is something I wasn’t expecting. I can almost imagine some big EDM DJ swooping in, giving this a few tweaks and playing it at some massive rave.

WD: I know what you mean in terms of that song as because the chorus has this rising synth part. I can’t name you any names but when I was 15 and living with my parents in Southampton I used to go on Winamp and I used to listen to trance music non-stop, for days on end. It was weird because after that period I didn’t go back to dance music for a long time really but at the time it really appealed to me. But I never tried making anything like that before now, there are few things about that song… a few chords and cadences that are of that style. And I think those are just ingrained in me and they just kind of come out.

That is the first in a triptych of club-influenced tunes, and second ‘Hearts That Never’, is definitely a dance track. How much does going out in London clubbing influence you?

WD: Hugely. It’s only over the last few years that I’ve really got into that world. I remember going to a Blackest Ever Black night two years ago and Vatican Shadow were playing at that but that’s not really been my current experience of going clubbing as much as watching Perc. To be honest, Ali [Wells] has been one of my biggest influences. There’s just something about his brand of industrial techno that I find really… it makes me dance like nothing else as well. There’s just something about how intense it is. But when you talk to him he couldn’t be more different to the music he makes. There have been mainly countless nights at Corsica Studios, listening to industrial techno.

I think I first became aware of a style of electronic music which was designed to give the listener at home or on headphones a similar sense to what they would feel when they heard a much more minimal song out in a club, via acts like Underworld and I get a similar sort of feeling from some of the tracks on Culture Of Volume. These tracks are not necessarily going to get played by a techno DJ as they are but it gives me that kind of feeling at one step removed, just going about my business during the day.

WD: That was actually a consideration of mine when I made this album. I felt if I was going to include dance tracks on a pop record even though I’m not actually aiming to be a dance producer then I would have to make the sound reflect how much this music has had an effect on me without actually making music exactly like that. Because I have so much respect for that scene and what that culture has given to me as a producer and as a person, I didn’t want to look like I was just dabbling for no good reason. So for me it was a case of learning how to take dance music and pass it through the filter in my head and make it unique to my experience of dance music.

And then we move on to ‘Entirety’. In terms of texture and intensity, why did you go for this huge peak in the middle of the album?

WD: In terms of momentum I put this track where it is because it’s the same BPM as ‘Hearts That Never’ but also because I was thinking about how best to big up the emotional impact of ‘Carousel’ which comes after it. So the contrast between the two songs was key and if it had been any other song before it, would ‘Carousel’ have sounded as good?

This is what I was leading up to. In terms of volume and intensity, ‘Entirety’ is the peak of the album but actually the real peak of the album, is ‘Carousel’, even though it’s the slowest. This is the real key moment of the LP. It’s a great track, how long did it take you to write?

WD: Almost surprisingly easy and it’s the reason why it’s my favourite. While everything else has been quite meticulously put together this one came out quite easily so I’m more in awe of it. There is something that seems quite raw about it. I had the end part to this track for ages. I thought it might be a small vignette, like one of those really short instrumentals that you get on Another Green World by Brian Eno. You fade it in and fade it out and then it’s gone. But then I thought, ‘No, I kind of want it to keep on going.’ It’s really only one chord so in terms of musical structure it’s very simple but getting the right sound and right balance was difficult. I don’t play it to a click or anything like that, the chorus is in bars but the rest of it, I just played by how it felt. I recorded the demo vocals as I was recording it. It only took me an afternoon that one, it was really weird. You try so hard to chase those songs but it’s when you aren’t chasing them that you catch up with them.

Can you tell me how you came to work with Graham Sutton?

WD: My old band, Doyle And The Fourfathers made the Olympics Critical EP before we broke up in early 2012 and Graham mixed it. We felt that we needed someone to bring it out of the space that we’d created it in and we needed someone to challenge us a bit. We never met him or worked with him, we just sent him the tracks because he was living in Argentina at the time.

Did you know about his background?

WD: I only knew him through his work with British Sea Power because they’re one of my all time favourite groups – I think they’re amazing. I remember buying Do You Like Rock Music when it came out and noticing the producer name then. But I never went in search of Bark Psychosis or anything until I got him to do the mix of Culture Of Volume and then I went back to the last record he made, Codename: Dustsucker and then back into Hex, and I was like, “Woah, I’m well into that.” Then I got into the These New Puritans record Hidden as well.

So we’d worked with him but not met him before. The first time I met him he was working with These New Puritans finishing off Field Of Reeds and living in Brighton. I played a show in early 2013 at the Green Door Store and I’d sent him the same demo that I gave to you because the band had ended and I just wanted to let him know that I was still doing stuff. I wanted him to keep in touch because I admired him a lot. And he came to the gig, we hit it off and I kept in touch with him. And then Field Of Reeds came out and it was like my favourite record. And I kept on running into him at gigs and then at the Grumbling Fur gig at Total Refreshment Centre, I asked if he wanted to mix the record. I said to him, “Look I’ve been mixing this record as I’ve been going along because that’s the way I’ve been working but I feel it needs an extra step up.” We did it over the space of three weeks, most of the time he was on his own. It was quite important for me to relinquish control over the project once all of my parts were done. As much as I wanted to sit in the room with him, I thought it was important to give it to someone with their own pair of ears so they could have their own interpretation of it and then work backwards from there. And he did a great fucking job.

Did he just mix it?

WD: Well I’ve credited him with additional production on the album. I sent him the unmixed demos and he said, “I like it.” So we met up at XL’s studios to listen to it in detail. And straight away during the first track he said, ‘That’s too long.’ And I was like, “Ok…” because we hadn’t discussed what his involvement was going to be. We didn’t lose any tracks but the whole thing in its entirety changed because of him. I gave him everything, all my audio and midi files from day one. He could see everything I’d muted and was not including in the tracks, so he was able to go through and ‘resurrect’ certain tracks, he could go through and edit it again.

Bring back the melodica solo…

WD: Exactly. We finished the mixing in three days of non-stop 10am to 4am sessions with very little sleep in between. And he’s been at the forefront of such amazing British music for such a long time. I feel like people don’t know about him for some weird reason.

He’s a really down to Earth guy Graham…

WD: Well, that was really important to me because I really liked hanging out with him. And that’s been my modus operandi the whole time and it’s really worked to my advantage because I only hang out with people who I actually like. I know a lot of artists and musicians who would never even go for a drink with people they work with. Well, life’s too short for that, isn’t it? But they do it for opportunity’s sake. I’d sooner it took longer and I find the right people.

So, no Damon Albarn and Flea on the next record then. How did you find the experience of making the album overall?

WD: I guess what I haven’t mentioned so far is that it was a pain in the fucking arse. I suppose every record is going to be like that to some extent or other.

Why?

WD: Because it’s like banging your head against a wall 95% of the time… with the other 5% being achievement and euphoria… “Yes! I’ve got it!” When you realise what a particular chord or drum fill or flourish means, it’s great, but the rest of the time it feels like total futility. The home stretch is where it all starts to make sense. When you start pulling everything together is when it clicks, you’re like, “I get it now.” But it takes two years to get to that point and before that it’s really frustrating. You have all of these great ideas regarding what you want it to be like but it takes ages for anything to actually happen.

Do you find it emotionally uncomfortable, or upsetting or depressing to write and perform certain songs?

WD: Writing, yes. Because I suppose you’re taking songs from certain [head] spaces and you’re doing this to frame darker aspects of your self. You’re doing this to give them a bit of context or to frame them in a certain way so then maybe you’re not as terrified of what it is anymore. But you are at one step removed, otherwise you wouldn’t get any work done. I find that I’m always referencing what it felt like to be in those situations mentally rather than being in them at the time of writing. I don’t know… you must feel like that writing sometimes. You can’t be in that space all the time.

I find that writing about personal things can make me extremely depressed. I think people presume that it’s going to be really cathartic but not for me, no.

WD: Yeah. Performing… well, with performing you become so numb to it after a while. I played my last show of last year in Istanbul and it was the end of a cycle I guess, I knew I was going to be retiring certain songs from the set and that I wouldn’t be playing them again for a while. ‘Glitter Recession’ for example won’t pop up in a set any time soon because it was the start of a set and now I’ve got a new one. And ‘Granular Piano’ as well, which is a really emotional song, so playing that for the last time was really like, ‘Woah.’ I afforded it that importance because I wanted it to have that importance. I have a really emotional connection to it. But normally, in a way, it’s a bit like choreography. There’s a certain sense to which you’re just going through the motions emotionally. It doesn’t mean you can’t be emotional and act emotionally but it doesn’t often take you back to the space you were in emotionally when you wrote it.

So when you write a certain melody, like ‘Don’t Look Backwards’, do you get a eureka moment?

WD: That’s one of my favourite bits of doing what I do because writing a melody is really fucking hard to do. But if you do it you feel a real sense of achievement. So the pop world that I’m part of – and I don’t mean the mega-mainstream pop world but more of an indie pop world on labels such as XL for example – the focus isn’t normally on melody as much as it used to be. The emphasis tends to be more on rhythm for example. Which is good but I feel like melody is so underplayed. I get more of a kick out of that than anything else when I’m listening to music and certainly when I’m writing music and I like to be able to write something that hasn’t been written before. And that’s one of the most totally amazing things about doing this.

Was there a specific carousel you were thinking about?

WD: When you’re a child, carousels can embody the total freedom of being a really young person without any anxieties or responsibilities but those same things that make you feel free are the same things that make you seem enclosed as you grow up. So the imagery of a carousel in perpetual motion means something you can’t get off, even if you were enjoying it to begin with. But now you’re on it and it’s spinning round… until you’re dead basically. [LAUGHS]

What does the title of the new album mean?

WD: It’s a partial quote from the poet Rick Holland. He’s a really nice guy. He came to watch one of my shows in Leeds. I got into him because of that record he did with Brian Eno, which I really loved. Then I bought his book, Story The Flowers. The whole line is nothing to do with the record but I really liked it…. the phrase really meant a lot to me and really summed up the last two years to me. Volume could have been talking about noise or capacity.

I think I’ve really taken the meaning of “culture of volume” out of context with his poem though. It means something else to me entirely. It just stuck in my mind for a while after reading it and I thought it was an evocative and potentially fitting title. This album is my musical diary of the last two years, where I have really entered and engaged with the culture of volume.

I should also say, Rick’s book Story The Flowers has always been a good source of inspiration. I find it difficult with words and I don’t get much lyrical inspiration from reading prose. Rick’s poetry was introduced to me via his work with Eno (which helps), but I’ve always found his own work really beautiful and it has referenced certain place names and resembled a few of my experiences and thoughts – but articulated in a much more poetic way.

What’s the cover art going to be and who did it?

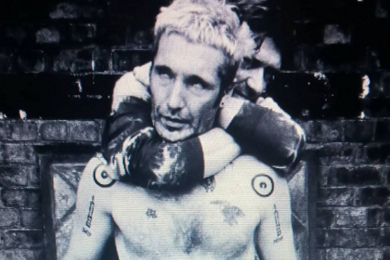

WD: I’ve been working with Dan Tombs who I met through touring with Factory Floor and his work with Perc and Luke Abbott. We’ve been getting on really well and I’ve been seeing a lot of him because he’s been doing visuals for Jon Hopkins and I’ve been at all the same festivals as Jon. It’s quite an interesting story actually, basically some archivists found floppy discs from when the first Amiga came out and were endorsed by Andy Warhol. They gave him a shit ton of money and free computers to endorse their new graphic software. He made a couple of really cool self-portraits. I saw it on one of those viral features that go round on social media. He looked really cool and it didn’t really look like his style. (I’m not a massive fan of his work to be honest, I thought he had a lot of good ideas and I think the mythology about him is really interesting but actually what he created, I’m not a huge fan of.) But how he looked in these self-portraits reminded me of how the recorded sounded in places. So I thought, “OK, what’s the best thing to do here? I think what I want to do is to use the same software on an Amiga and make a self-portrait. Not to ape Andy Warhol’s style on the floppy discs that were discovered but just as an inspiration for the process.” I mentioned this to Dan, he went to a photographer friend of his who took a load of photos of me and then Dan started feeding them into the Amiga. Except he blew up the Amiga so had to use a friend’s. But in the end we didn’t end up using the software – we didn’t get round to it. When he imported one of the images there was this really weird error and rather than trying to correct it he captured it and showed it to me. It had stretched my face in a really weird way. The pixels on an Amiga are really sharp and clear… it’s amazing. There is something quite weird and artificial about it. We made a composite out of the original photos we took; we spent quite a lot of time doing it and I’m really pleased with the results.

Now that the dust has settled, can you sum up how you feel about the whole Mercury experience?

WD: In the terms of us doing an indie campaign via Stolen Records, I feel like it was a complete victory. In terms of how we did in this country, the campaign couldn’t have gone any better. And in fact even if I had won it, it wouldn’t have been as good as having been just nominated for it. It was quite funny. On the week of the announcement I finished the last bit of recording for Culture Of Volume and on the night of the awards ceremony was the same week we finished the mix. It was really weird, so after I got nominated, I felt like I was in a really strong position, whatever happened with the prize. During the whole press cycle surrounding the prize, everyone always asks you, “Do you believe in the curse of the Mercury?” – which is kind of bullshit – but I do think it probably has some kind of impact on some people who win it or are nominated if they haven’t started on their next record yet especially if they’ve only just put out a debut album – instead of just drifting off in obscurity to make the next record, you’re now in the spotlight while having to make the next record. But for us, it came right at the end of the process for finishing our next record so we didn’t need to worry about it. Even if we had have won it nothing would have changed. We were sending it off to get mastered a couple of weeks later. There was literally nothing I could have done differently and because of that I enjoyed the whole process.

What was the ceremony like? Did you meet anyone interesting?

WD: It was great. It was really well put together and they looked after you really well… although no one had a dressing room. Everyone had to be in this weird communal space at the back. That bit wasn’t very glamorous. Andy [Inglis, EIY manager] found a room through these double doors down a corridor. We ended up in some disused office with rubble and wood in it and that’s where I got changed. It looked like a set from The Walking Dead. I talked to the winners Young Fathers, this batshit insane hip hop group from Edinburgh and they are the most lovely people. Perhaps it was understandable that they got all that shit for just saying “Cheers” and walking off but I don’t think it was an act. I met them the week before at a festival we were both playing in Dublin but we had a really nice time together chilling out. Lovely sweet people with really good ideas. I was made up they won.

And when did you start writing your third album?

WD: Early in 2014. [LAUGHS]

How long will East India Youth last? Do you have ambitions beyond it?

WD: I was trying to think recently whether it will be summed up by a period of time or whether it’s a lifelong thing. Where does me end and East India Youth begin… Because I’ve got such clear ideas about the third album and I have done for a long time, that I think that might be a natural place to conclude it. Which doesn’t mean that I’d stop making music, just that it was the natural place to stop the project. But I don’t know yet, I might get carried away and do loads more. We’ll have to wait and see.