It all came extremely quickly to King Crimson. After just five shows, they found themselves supporting The Rolling Stones at Hyde Park in July of 1969, playing in front of somewhere between a quarter and half a million people. The endorsements came thick and fast after that. Following one particularly impressive performance in London, Jimi Hendrix enthusiastically stepped forward to press the flesh with Robert Fripp: “Shake my left hand because it’s closer to my heart,” he reportedly said. Then Pete Townshend called their debut album In The Court Of The Crimson King “an uncanny masterpiece”. Released precisely 335 days after the group had formed, it peaked at number five in the UK albums charts.

Conversely, by the time Robert Fripp and a slowly disintegrating third lineup of King Crimson came to record Red five years later, their de facto leader could only see end times ahead. The day before entering Olympic Studios, Fripp had been reading John G. Bennett’s book Is There Life On Earth?, an introduction to the teachings of philosopher and mystic George Gurdjieff, who believed that humans were able to reach a higher state of consciousness beyond the “waking sleep” of everyday existence. It would change the course of Fripp’s life. “The top of my head blew off,” he recalled, speaking to Melody Maker in 1979. “That’s the easiest way of describing it. And for a period of three to six months it was impossible for me to function.” But function, he must. “In terms of Crimson, it simply became apparent to me on a night in July 1974, that I would have to leave – even though the following day we were to begin recording Red.”

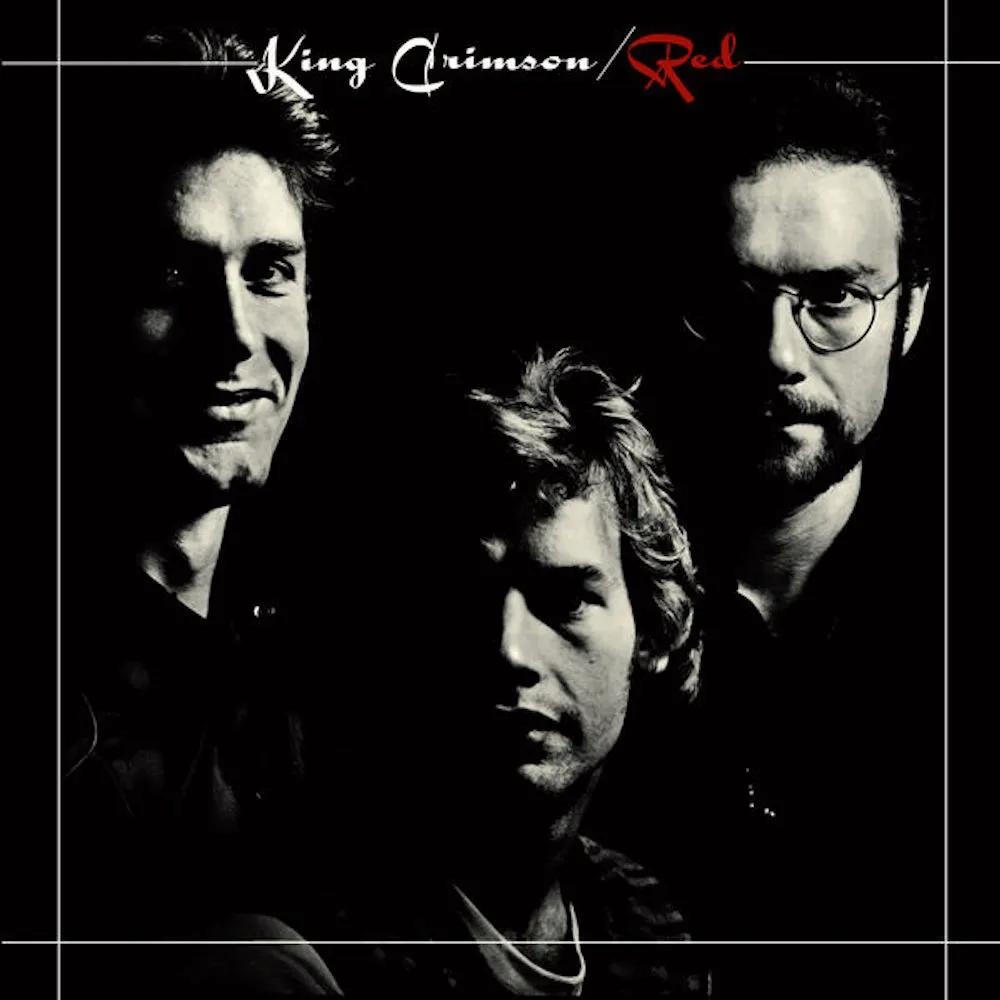

Where In The Court Of The Crimson King had been met with fanfare and a palpable sense that popular music had been changed as a result of its existence, Red’s release was a non-event. The album, recorded by the slimmed down trio of Fripp, bassist and singer John Wetton and former Yes drummer Bill Bruford, did receive broadly favourable reviews, with critics comparing it to John McLaughlin’s fusionists The Mahavishnu Orchestra, but on its release in October of that year it limped into the UK charts at number 45, hanging around for just one week.

In the run up to the recording, however, a sense of momentum had been building, especially in America. A show played on 1 July in Central Park really hit the spot. Fripp called it “the first gig since the 1969 Crimson where the bottom of my spine registered ‘out of this world‘ to the same degree”. A newly radicalised Robert Fripp spent much of the album’s recording in a contemplative silence that could have been interpreted as passive aggression were it not for his ceding uncharacteristically to the other players’ artistic demands, suggesting instead that he’d undergone some kind of psychic change. It’s hard to contemplate how different or how more focused Red might have been, knowing now that the band leader’s mind was elsewhere throughout the process.

A week before its release on 25 September came the bombshell: Fripp announced that King Crimson had “ceased to exist” and was “completely over for ever and ever”. There’d be no tour or promotion from the band, which also would have hurt sales considerably.

Not that that bothered Fripp: his mind was too occupied with existential questions. He told Rolling Stone in December of that same year that he envisaged a societal breakdown on “a colossal scale”, a process of decadence and renewal that had already begun and would culminate in the early 1990s. “It’s no doomy thing – for the new world to flourish the old has to die,” he said, apparently with some relish. “But the depression era of the thirties will look like a Sunday outing compared to this apocalypse. I shall be blowing a bugle loudly from the sidelines.”

The sideline Fripp retreated to was Sherborne House in Gloucestershire, a 17th century Grade II-listed Georgian house where he planned to live a monastic existence following the esoteric teachings of Gurdjieff, known as The Fourth Way. Meanwhile, Wetton went off to temporarily take up bass for Roxy Music (a perpetual revolving door), and Bruford briefly joined Gong for a tour around France. Having just made the leap from Yes to Crimson, jumped ship from the former in 1972 just as they were in the process of selling a million copies of Close To The Edge – he was clearly the most put out by the split. “Bill was upset because Bill was very committed to the group, he was still getting an awful lot from it,” Fripp told International Musician & Recording World in 1975. The change of scene from Fripp’s austere crew to psychedelic magus and Gong leader Daevid Allen’s wild farmhouse commune in France was apparently all too much.

That said, not everybody had conformed to the high standards of the abstemious Fripp. Speaking to Innerviews in 2019, two years after Wetton’s death, Fripp admitted that “relations with John professionally became difficult because, John at the time – as he would later graciously and freely acknowledge – was doing a lot of coke and drinking. There were one or two very bad moments like at the Academy Of Music on 14th Street in New York. We had two shows. The second show began about 1:00 in the morning, and we came on a little after that I think. John was a bit revved from the first show with coke. So, management took him on the roof and gave him a donut and he washed it down with a little liquor. We walked onstage and played a piece called ‘Doctor Diamond’. I knew from the first minute that the show was dead.” Fripp reserved praise for Wetton, who’d turned things around in 12-step recovery before his death, stating that “John’s life was a triumph.”

Back to 1974 where everything was done and dusted… except, of course, it wasn’t. Fripp and Bruford would return with an all new King Crimson in 1981, while Red would only grow in stature and reputation after being criminally misunderstood on release, like Gainsbourg’s Histoire De Melody Nelson, Miles Davis’ On The Corner or Nirvana’s Bleach. As with those albums, it’s difficult to comprehend now what listeners were missing at the time. Red is practically faultless, save, perhaps, for one hard-to-get-excited-about foray into atmospheric free jazz (‘Providence’), though the sprawling, epic roller coaster of emotion and dexterity that follows (‘Starless’) surely makes up for any shortfall.

Half a century later, the album stands as the perfect distillation of the three-piece. It’s the exemplar of how to make a rock record with the barest of bones – admittedly augmented with clever, sporadic interjections of cornet, cello, oboe and sax by guest players. Red has a clarity and an emotional kick and at times it weeps like an open wound. What’s more, the pain from all the existential angst and the internal friction is channelled in a way that the perennially overrated Cream could have only dreamed of. Hendrix might have shaken Fripp’s fist enthusiastically with both hands had he lived to hear Red – The Jimi Hendrix Experience, after all, were really the Jimi Hendrix Experiment, with three wilful musicians playing against each other, a swirling tornado of chaos that somehow worked but lacked the collective precision or cohesion of the Crims’ seventh.

Later down the line, Kurt Cobain did dream of achieving those heights: Nirvana’s frontman had apparently been listening to Red intensively and had hoped to harness some of its raw energy for In Utero – with the guidance of Steve Albini, that wish was partially realised, with stylistic similarities between tracks like ‘Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge On Seattle’ and ‘One More Red Nightmare’ apparent, though not glaringly so. A key influence on the biggest alternative rock band of them all, then, Red was also the precursor for both math rock and avant-garde metal, a muscular, pared-down fulfilment of what had begun with Larks’ Tongues In Aspic the year before.

Red’s impact wouldn’t really be felt until the Discipline-era King Crimson were hammering out intricately woven gamelan phrases with Tony Levin on Chapman stick in the first half of the 1980s. Their audience would need almost a decade to catch up, given all the ground they covered. Therefore back in 1974, it would have been easy to assume the highly schismatic Crimson and its facilitator Fripp were agents of their own undoing. To paraphrase Oscar Wilde: to lose one musician may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose 12 in the space of five years looks very careless. First to go were Ian McDonald and Michael Giles, who quit unexpectedly while on the road in America in early 1970, the kind of hammer blow that bands seldom recover from. Commercially that might be true of Crimson, though it was anything but the case artistically.

Like The Fall, King Crimson became an almost occultist institution led by one intransigent intermediary, working for a clandestine purpose that nobody else was party to. The musicians in both bands would be forced to prostrate themselves in service to these respective entities, often ending up broken. Members of both crews testified to periods that were so mentally punishing that the work seemed to be the only thing driving them on; Dave Simpson’s The Fallen is a litany of personal stories of woe and minimum wage slavery while Adrian Belew claimed the intensity of playing in Crimson made his hair fall out. King Crimson had a more modest turnover than The Fall, with 23 main players and around 10 axillary musicians who either contributed to studio albums, tours, or in Peter Sinfield and Richard Palmer-James’ case, lyrics – that’s around half the churn of The Fall, though it should be noted that Crimson would sit inactive for long periods of time. “King Crimson is, as always, more a way of doing things,” Fripp once said. “When there is nothing to be done, nothing is done: Crimson disappears. When there is music to be played, Crimson reappears.”

As the saying almost goes, if it’s Fripp and your granny on bongos in 13/4, it’s King Crimson; the difference being that most of the musicians in The Fall were plucked from obscurity and returned there once they were no longer of use, whereas Fripp was able to attract big name virtuosos like Bruford and Belew from other huge bands like Yes and Talking Heads, the damage done to them lived out in public afterwards.

Singer and bass player Greg Lake left soon after McDonald and Giles in 1970, and in 1972, Fripp dismissed the refreshed lineup of Mel Collins, Boz Burrell and Ian Wallace after their fourth studio album Islands, with lyricist Sinfield – the last remaining founding member, whose words had shaped their early incarnation and supposedly summoned the shadowy figure of the crimson king himself – also shown the door. With him gone, so too departed the mediaeval imagery of purple pipers, jugglers and jesters and Prince Rupert’s tears of glass. The more earthy and contemporary lyrics would be shared amongst Fripp, Wetton and Palmer-James; Red’s ‘Fallen Angel’, for instance, is a lament for a teenage brother felled in a New York gangland killing.

Fripp, Wetton and Bruford were joined on 1973’s Larks’ Tongues In Aspic by Scottish jazz percussionist Jamie Muir, a flamboyant, feathery presence with a dashing handlebar moustache with shaped curls, and the violinist David Cross. A bold reinvention took place. “It would still fall under the description of ‘prog’, but a different prog,” wrote Pete Tomsett in Fifty Shades Of Crimson, “one that bore little relation to Crimson Mk I, and none at all to Mk II. On Larks, the more recognisably rock elements were surrounded by all manner of atmospheric diversions, sound experiments and the sort of time signatures you would usually find in jazz.” Muir didn’t last long in the group either, though his presence brought a mystical flourish to that record.

David Cross would be next to take a ride in the ejector seat, the twelfth member to depart. Without Muir adding balance, he found it increasingly difficult to impose himself or his violin parts on an increasingly calcifying core made up of stronger personalities. He appears on one track on Red, though the previous album Starless And Bible Black, released in March 1974, would prove to be his swansong. It’s a peculiar cut-and-shut of an album featuring studio adorned embellishments of live recordings for the most part. It makes for a confused mix of improvisation and experimentation. While it has its moments, its unresolved nature makes it feel oddly liminal, like an open-ended episode stuck between a pilot and a season finale.

For anyone who would have been disappointed by Starless And Bible Black, they’d only have seven months to wait for King Crimson to get it right on Red. Of course, by that point, few people were paying attention; Fripp included, if that can be believed. The guitarist was dismissive of the album at the time, but there’s no hint of a musician going through the motions and deferring to muscle memory. Since then, the societal collapse that Fripp predicted is taking longer to come to fruition than he anticipated. Red, on the other hand, is now seen by a growing number of admirers as King Crimson’s true masterpiece. Things may have happened very quickly for King Crimson at the beginning, but Red is slow burning its way into the pantheon.