"We like the K-West because it’s so close to the Westfield", says Susan Ann Sulley, amping up her South Yorkshire accent by a couple of notches, while looking provocatively at the other two members of The Human League. Joanne Catherall giggles as if it is mischievous for them to be planning a shopping trip to a huge mall when in London for a day of press. "I’m sure Philip would prefer that we’d stayed in Claridges so he could swan round the West End", continues Susan almost giddily, her eyes glittering.

Philip Oakey purses his lips slightly and smiles indulgently at the two junior members of The Human League, pretending valiantly that his mind is on more esoteric matters than their shopping based banter.

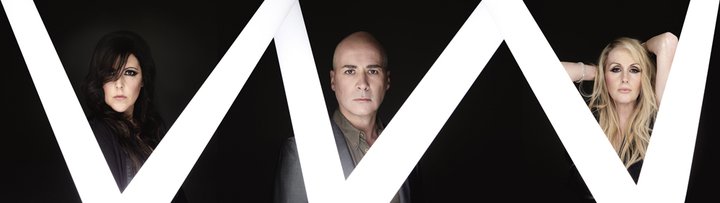

The trio are sat in the restaurant of a West London hotel at breakfast time but they’re dressed for any eventuality. It is, for reasons I can’t quite put my finger on, really great to see The Human League looking this good, dressed up to the nines as if they’re about to go out to some chic club in New York and not to an interview and then shopping. For more obvious reasons it’s also good to see the band in such good spirits. They revel in each others’ company, the two girls teasing the lead singer but also laughing heartily at his jokes.

The Human League mark one formed in Sheffield in 1977 as one of the UK’s first synthpop groups. They were declared the sound of the future by David Bowie and released a pair of patchy but occasionally astounding albums, Travelogue and Reproduction, as well as the seminal ‘Being Boiled’ 7". Their original manager Bob Last used simmering tensions between singer Philip Oakey and founding member Martyn Ware to manufacture a split. His intention was to try and set up Ware as a one-man production house for Virgin under the name of British Electric Foundation — leaving the League to pursue pop success, without the perceived intellectual baggage of their arty member. Things didn’t quite go according to plan: another member of The Human League, Ian Craig Marsh, left with Ware, and they recruited Glenn Gregory to form Heaven 17. Whether tricked or not, Ware had every right to feel upset after getting kicked out of his own band. The drive that eventually made Heaven 17 chart-toppers was, no doubt, partly a desire to get back at the people who thought he was standing in the way of the group’s success. To prove them wrong.

Ironically, however, The Human League mark two were feeling something similar in 1981. While they’d been press darlings up until this point, this changed after Oakey recruited two 17-year-old girls as backing dancers and singers after his then-girlfriend saw them performing a complex routine to Visage’s ‘Fade To Grey’ in a local nightclub. Despite being pretty much written off by the media, the band — Adrian Wright, Oakey and the two teenage members (and session musician Ian Burden from local band Graph) — quickly released two singles: first ‘Boys and Girls’, then the excellent ‘Sound Of The Crowd’. After further bolstering their line-up with Jo Callis of the recently defunct Rezillos, the League scored their first top ten hit with ‘Love Action (I Believe In Love)’.

Showing remarkable industry, they released another smash hit in the shape of ‘Open Your Heart’ and followed this with the album Dare. They also found time to write, record and release their next single, ‘Don’t You Want Me?’, which would sell over two million copies and become the 25th highest selling UK single of all time.

It’s worth mentioning this as it’s the only thing that resembles a cloud passing momentarily in front of the sun when you meet the group. Susan, like an actor referring to Macbeth as "The Scottish Play", simply calls it "that song". Despite having a distinguished career post-Dare the group clearly feel embattled by the monolithic shadow the album casts. (And to be fair, I probably don’t help by asking plenty of questions about it.)

It’s ten years since their last album, Secrets, suffered unfairly from record label Papillon collapsing just after its release. Now back with a thoroughly modern sounding album Credo, released next month on Wall Of Sound, things are looking much healthier for them. The album, recorded in conjunction with Sheffield electronic act I, Monster, not only comes out at a time when interest in vintage synth sounds has reached a peak, it’s also wisely aimed at dancefloors rather than radio playlists. It seems like an ideal time to ask them about the albums that have bookended the career of The Human League mark two so far.

When I was listening to Credo this morning, I was thinking it’s been ten years since Secrets in 2001: what’s been going on since then?

Joanne Catherall: Well, our last record didn’t do as well as expected which was partially because the record label went bust on the day it was released. After that we started doing a bit of live work and instead of actively looking for a label which is what we’d done in the past we decided to concentrate on the live thing. We’d got a manager who made it so we could earn money from that. We did this for maybe seven years and then felt that we needed some new tracks and Philip started writing them with our drummer Rob. Eventually it came to the notice of Mark Jones [Wall Of Sound] and he came to us with a proposal: make a Human League album.

I’ve seen you live a few times and I think the last time was at a house music festival a few years ago called Homelands. And while there’s nothing wrong with the 80s revival circuit per se, I do think it’s nice to see you being presented in the context of being an electronic group again.

Susan Ann Sulley: I think we’ve got this 30-year history that can kick us in the head, it can be hard work dealing with it. Sometimes these revival things, you do them for the money because you need to earn some. But we wanted to get back and do something else. In this country we have a bit of a problem because we’re known as the group that sang ‘Don’t You Want Me’. We’ve made a lot more records than that. We wanted to get back to making music again so we wouldn’t be just stuck in that one genre.

Well, you’re in a much, much stronger position to do that now with outfits like Simian Mobile Disco and people like Little Boots and La Roux in the charts. Also you only have to look on eBay now to see how much more expensive it is to buy synthesizer gear. Obviously for a dyed in the wool synthpop fan like myself, who grew up listening to Gary Numan, yourself and and OMD, this is good news. But does it feel like the time is right to you?

Philip Oakey: I don’t know if it’s because of all that or just because we’re such single minded people. It’s good that all that stuff is out there and I’m glad you mentioned Simian Mobile Disco because when we heard Attack Decay Sustain Release we were like, ‘My God! That’s the record we would have made in 1978 if we had been able to get our sequencers to actually stay in time. Back then our biggest problem was we used synths to make bass drums and they would do two good hits, then two dodgy ones, then two good ones . . . but we couldn’t do anything about it, we didn’t have a sampler, we just had to stick with it the way it was. So the basic palette was the one we singlemindedly just stuck at. It got into my head with Walter Carlos, Giorgio Moroder, Donna Summer and even Keith Emmerson. It was around that period that it occured to me: analogue synths may change a little bit while you’re playing them but you don’t have to play them too much. You can have a little think about it while you’re doing it. And then we just added drum machines later on. We made two albums [Travelogue, Reproduction] without drum machines. Then we got a Boss DR 55 a drum machine with four skins on it. It had four crap sounds, but that’s exactly how we still work now.

I think I should point out here that Credo isn’t an exercise in early 80s synth fetishism though. The new album with tracks like ‘Never Let Me Go’, is engaged with club culture. Is it important for you to keep on progressing sonically?

PO: I love club culture. I became single about ten years ago, so suddenly I wasn’t forced to be home at a certain time any more and it was just when Gatecrasher was on its second wave. When Paul Van Dyk and people like that were huge. We got to know the guys who owned it and all the DJs and this connected me back to the music I used to buy when I was younger… even to Terry Riley and Philip Glass. I think clubbing music is the most exciting ever but clubbing music now is only really the same as when the Bee Gees came out. It was so exciting when disco started. It meant that much to people, that they could dance to it. The first single that we released [‘Night People’] from Credo was not designed to go on the radio; it was designed to go into clubs, to have remixes but suddenly it’s a single and it got played on Radio 2. What’s the point? There’s no one listening to that kind of music on Radio 2. It’s really strange.

What about the other extreme? Have you heard from DJs in clubs who have been playing ‘Night People’?

SAS: Yeah, we got a really good response. People have been really positive.

JC: I still think this version of the group found success initially by coming out of the clubs with the remixes that Martin Rushent was doing. And that’s still what we want to do now.

PO: We were kind of like the first commercial pop dub group. People were doing extended remixes and extended instrumental versions [in the early 80s]. And while we were doing our biggest album [Dare] our producer was in New York listening to Grandmaster Flash. We ended up doing an album called Love And Dancing [credited to The League Unlimited Orchestra] which was so innovative. Martin was splicing in empty tape so the music would jerk, and no one had done stuff like this before. The guys mastering the album were saying, ‘You can’t do this.’ It was that original. But that’s why we signed to Wall Of Sound this time. First of all Mark is incredibly enthusiastic and knows music but after that he knows DJs and can get remixes. To get a Cerrone remix after 30 years… and it’s good.

SAS: We don’t think that people who are fans of The Human League because of that song will get this version of the group. They won’t understand. They want to stay there and be nostalgic and get that warm funny feeling when they hear the first few bars of that song… This is not really for them, this is for what’s going on now. And I know you’re not supposed to still be doing it after 30 years, you’re supposed to have stopped by now.

PO: We’re supposed to be playing ballads on cruise ships.

Is this more The Human League who recorded ‘Hard Times’?

SAS: Yeah, I think it is.

PO: That’s the one from that time that they still play in some clubs. Although there was a conscious effort on songs such as ‘Privilege’ with the writing on it, we wanted to say: that will sit next to ‘Being Boiled’. Our producers are cleverer than us so they’ve taken it somewhere else but the idea was that you’d be able to mix the two together. That track is fixed in 1978.

Credo is a very Sheffield-based affair isn’t it?

SAS: We’ve always tried really hard not to do that. Have you ever been to Sheffield? It’s a big city but it’s also sort of like a small town. Everybody knows everybody else. Even when we started playing live about 15 years ago we tried really hard to not get Sheffield musicians because if we fell out with them we’d end up seeing them down town, and we didn’t want to do that and suddenly even the bloody producers are from Sheffield.

For those who don’t know, the production team are I, Monster who are probably best known for their ‘Daydream In Blue’ single. How did you meet them and how was it working with them? I believe it was quite a rapid process.

PO: Occasionally, when I’m drunk in bars people ask me to sing on their records and I say yes.

SAS: Ha ha ha! And you always regret it the next day! Ha ha ha!

PO: They had this song called ‘The First Man In Space’ with words by Jarvis Cocker and they wanted my voice on it, so I did that. I think Jarrod [Gosling] liked my voice. And later Dean [Honer] was producing a potentially great Sheffield band called Hive and I sang on their record but I don’t think it ever came out. I really like I, Monster by the way, which is weird because I don’t usually like lounge music but they’re just this side of it and they’re like the Moody Blues as well, which I like. But I was down the park one day walking the dog and Dean was there taking his kids out and he asked what I’d been up to and I told him he we’d recorded some tracks. And he just looked at me in the way that he does and said, ‘Oh, we’ll do some mixes for you.’ We gave him some 24-tracks and the first thing he said was, ‘These need simplifying.’ And that’s the key I think.

He took it away and erased all the drums, he kept some of the bits he liked. He added a few little tricks. He always adds a bit of noise in spare bars that you aren’t expecting and we just thought, ‘That’s fantastic.’ The first thing he gave us back, ‘Sky’ we just went, ‘Wow, how has he turned that into this?’ They’ve got a really good collection of synths. Dean’s got a Mini Moog, an OSCar, a Pro-One and really old stuff. They’ve got a Mellotron. Have you heard of an Optigan? You’ve got a great big disc of tracks on optical film and it will do a whole track and by pressing keys you can add rhythms and vocals. And they’ve even got a clavioline which is what The Tornados used on ‘Telstar’. We’re collectors of old synths and so are they. They do the same thing that Simian Mobile Disco did when we went round to see them. They said: "Just play it and if you need to move it round later in pro-tools you can." You want that more organic feel. If you’re making trance then you need everything to be metronomic and exactly looped, but for us, we want something that’s less precise. The thing you get from analogue synths.

Even if it’s only on a subconscious level, your brain can tell. I know people who when they’re creating beats, they use programmes to move the beats around fractionally. Consciously you can’t tell what’s happened but you respond like you’re hearing a drummer rather than a machine.

JC: I think that’s true and that would definitely be the case for vocals as well. You can’t just sing one chorus and think, ‘Well, that’s the perfect take’ and then cut and paste it through the rest of the song. It sounds wrong but you wouldn’t necessarily realise that was the reason. They’re all in tune and they’re all in time but there’s something not quite right about it.

So obviously there’s something about Sheffield, isn’t there, in that it’s produced Clock DVA, Artery, Cabaret Voltaire, The Human League, Heaven 17. . . . A lot of people presume it’s the influence of heavy industry, in the way that they presume that the industry of Birmingham influenced heavy metal.

JC: I think it is, all of the bands that you’ve mentioned are of our generation and they grew up with the backdrop of the steel industry. It must guide you subconsciously. The sounds are already there, so perhaps that makes you more electronic. But Sheffield isn’t just about that; obviously you’ve got the Arctic Monkeys as well. It’s a very, very arty town. It’s a bit dull…

SAS: I think it is because it’s a bit boring. There isn’t much going on. You only have to go across the Pennines to Manchester and suddenly you’re in a different world; it’s very cosmopolitan. You come back to Sheffield and it’s a bit… boring! And I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing because it creates creativity.

But that’s why good bands don’t come from London. Ambitious bands move to London to become famous but that’s not the same thing.

PO: Adam and the Ants . . . Sorry, I’ve spent some time thinking about this.

Fair enough but even during punk and post-punk when you had a lot of people coming through, a lot of these bands were more associated with places like Bromley, which are satellite towns or else they came from squatted communities where people couldn’t afford any of the entertainment options that London offered.

PO: This was part of our development actually. Our first tour was with Siouxsie and the Banshees and they were from Bromley. They were very, very supportive, there was the Banshees, Spizzoil and us. That was when we were getting our ideas together. We had nothing at that stage. Even if we went as far as somewhere like Bristol we’d have to go back to Sheffield that night so The Banshees would pay for us to have a hotel room. It was really incredible. And immediately after that tour we went to Europe with Iggy Pop. It was the Soldier tour. It was an eye-opener. It was while all the drugs were still going on. You’d come to breakfast in the morning and there’d be a couple of people missing. And the others would be like, ‘Yeah, they got taken to hospital.’ We had no money. We’d be in places like the Munich Hilton and on the days that we actually played a show we’d get £15 but sometimes we only played two shows a week so it was quite tough. It was before Joanne and Suzanne joined!

SAS: We had it a bit tough as well!

Well, it’s 30 years since you both joined. And I’m not really that interested in ‘that song’ myself, or about Phil asking you to join after his girlfriend saw you dancing in a nightclub. But I am interested in Dare because like a lot of people my age I rushed out to buy it. In fact I remember the temperature in my house dropping when I brought it home. It felt like my dad was gearing up to go mad when he saw the cover. He didn’t say anything but his face said: "Adam Ant was bad enough but this is some right Fall Of Rome shit going on here." But it was like the album artwork that summed up the period. Did it feel like you’d nailed something significant with that?

JC: Well, I think the idea was that you couldn’t really tell whether it was a man or a woman on the cover, that it was quite androgynous. I know you could tell really. Also the idea was to cut off things that would age it. So instead of having a full on picture of how we looked then, the idea was a photograph that had the hair style, the clothes and the entire era cropped out of it. We were very concerned about all aspects of what it was going to be. The music was right, we’d got Martin Rushent. The seven people involved with making the album were all right and then the cover had to be right as well. It was all part of the package.

SAS: And at that stage we had nothing to lose. So we went all out to make it exactly how we wanted. It was somebody else’s money. We’d made an album that we were really, really happy with but I don’t think we ever thought it would sell like it did. The cover was a complete and utter rip off. It was the front cover from a copy of German Vogue magazine. Was it Brooke Shields?

PO: No, just a model.

SAS: I think even before we started recording it, he was like, ‘If we finish this, then this is what the cover is going to be like.’ Virgin went mental because we made them put a special glaze on it so it would look shiny and glossy, so it cost 55 pence per more to make per copy than any other album on the shelves that year.

PO: Our manager was an architecture student so he knew about how to do a double glaze, so the white would go yellow much slower than on other album covers.

JC: They went mad about it being a gatefold as well. In fact I don’t know how they got away with it.

PO: We got away with it because we already owed them so much money.

SAS: We had nothing to lose then. We didn’t have nice houses and cars and all the things that come with having a hit record. So when Simon Draper [founding member of Virgin Records along with Richard Branson and Nik Powell] told us to come to the Virgin offices and told us that it had to have guitars on it, we just said no. There was nothing they could do. They were contracted to put the record out and they’d already paid for it. But then when fame comes you start getting a bit scared and you suddenly don’t listen to your instincts any more.

I know from interviewing Martyn Ware and Glenn Gregory from Heaven 17 recently that for obvious reasons there was a certain sense of urgency to procedings after the split. Could you hear the drum beating in the background?

PO: Well, our first problem after they left was that we had some dates to do and at that stage of our lives, we owed Virgin an astronomical amount of money. It was something like £100,000. They agreed to split the debt with us but someone had to do the live dates otherwise we were going to get sued by promoters. Then we had to recruit people to do those dates. But we didn’t rush at Dare though did we?

SAS: No, not at all. I mean we didn’t even start out to make an album. We did ‘Sound Of The Crowd’ first and brought that out as a single. Then we did ‘Love Action’.

JC: Everyone forgets that after we did that tour and before we even did ‘Sound Of The Crowd’ and started on Dare, Phil and Adrian [Wright] did ‘Boys And Girls’. Even though we were on the cover of it, we didn’t have anything to do with the recording process.

Because you’d literally just joined?

SAS: It’s really weird: I think technically, we didn’t actually join until 1986. He never asked us to join, he only asked us to do the European leg of the tour that they were contracted to do. He asked us to do that, and it was four or five weeks in a Transit Van! But after four or five weeks of that, we all actually got on quite well. So when we got back from tour we’d be bumping into each other in nightclubs in Sheffield and about that time Adrian considered himself to be a photographer amongst other things, so he asked us if we wanted to be on the cover even though we don’t appear on it. I can’t believe we agreed!

JC: I know!

SAS: And then we did ‘Sound Of The Crowd’.

PO: Our manager was also managing The Rezillos who had just split up so that meant that Jo Callis was free to join the group. Jo had always got on with us really well. Adrian especially. They both collected toys I think.

JC: They liked Daleks… strange!

PO: Jo was a really good guitarist but he’d never really played keyboards. I think the manager had said to him, ‘Go and help them… they’re rubbish.’

SAS: To be fair, everyone at the time this was going on — NME, Sounds, everyone — they all said: "The talented two have left." Everyone thought we would fail.

To a certain extent Dare can be seen as a list of things that you were into: The Ramones, Get Carter, going out clubbing, 2000AD, Norman Wisdom…

PO: We were culture freaks. We loved music but we also loved film. Martyn and Ian were in a Sheffield theatre group called Meat Whistle.

And I tend to think of Dare as being synthpop’s Off The Wall in that any track could have been a single.

PO: ‘Get Carter’?

Joanne and Suzanne: Ha ha ha!

Alright smart arse. Apart from ‘Get Carter’… You two must have reacted to fame in a different way to Phil because he’d been plugging away for over five years. You two were thrust relatively quickly into the limelight. How did you find it?

SAS: Well, at first it was fun. Going to [Sheffield studio] Genetic … we’d never been to a proper recording studio before and then, there we were with proper headphones on and proper microphones, with a producer and engineers.

JC: When we did ‘Sound Of The Crowd’ it was fun. Doing Top Of The Pops was great because it was the programme that you’d always stayed in to watch all the way through your teenage life. It was only when the album came out and ‘Don’t You Want Me’ went huge that it went silly. Then we couldn’t go to a clothes shop without having to have the door locked behind us because there were so many people trying to get in after us.

SAS: I still remember the first time we went to New York and we got picked up in a limo. I was a little girl from Sheffield. I didn’t have wide horizons. I’d only been to Spain twice. Anyway I was very tired and I fell asleep. Our manager woke me up and said, ‘You have to see this now, because it will never be like this again.’ He lowered the window and there was that skyline of New York. And I cried. Because I was just a little girl from Sheffield seeing it for the first time. Those sort of things stay with you forever but all the other stuff that went with it, I didn’t like.

The single ‘Never Let Me Go’ is released on March 21 and the album Credo on March 28, both via Wall Of Sound