Listen to Heaven 17 (and early Human League) here!

It’s about an hour into a chat with Glenn Gregory and Martyn Ware, two of the original members of Heaven 17, and the pair are reminiscing fondly about their “Sgt. Pepper’s moment”. During the recording of their vastly under-appreciated third album How Men Are, they were indulging in a coke fuelled attempt to capture the angst of potential nuclear holocaust, the irradiated zeitgeist, that was in the air in 1984. A suited and shaven headed Gregory rolls his eyes at the ridiculousness of what he’s saying but you can tell he’s enjoying reliving the moment: “You know that noise at the beginning of ‘And That’s No Lie’? That’s like 128 tracks of vocals and we had this on a massive tape loop about the size of this entire restaurant, going round the studio, going round pencils, people’s arms, pillars, giving it that… Waaaoooaaarrrrgggghhhhhhh sound. We were getting really far out.”

This story may ring a bell of recognition with fans of Continuum’s excellent 33 1/3 series, but this will have nothing to do with The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The journalist Hugo Wilcken in his book on Low describes a similar scene in which David Bowie, Tony Visconti and other associates sat in an occult trance, a drug-induced state trying to orchestrate a giant tape loop according to arcane principles (or narcotic idiocy if you like). The rest of his time in Berlin, the Thin White Duke was reportedly to be found trying to mow down his coke dealer in a paranoid rage, sitting on his own in bars crying, using cocaine and whisky binges to cure his smack habit, trying to avoid contact with his wife and young son and losing his mind, hallucinating leaches all over his skin.

But ask H17 how it was being famous, even during their “Sgt. Pepper’s moment” and they only have one word: “Fantastic.”

Even at their most whacked out, it sounds like they were having the time of their lives. Gregory’s urbane foil Ware takes up the story dryly: “The sounds on our third album are quite weird. Martian, even. The album is closest we got to that stream of consciousness thing we were trying for with the lyrics. And capturing the paranoia of the times. And a drug crazed freedom of expression, if I’m totally honest.”

Gregory laughs: “When we were recording ‘Five Minutes To Midnight’ we constructed a special vocal booth out of corrugated iron to get that sound. And I was running around the outside of the studio to get out of breath and then racing up to the mic, [panting] ‘Break or be broken, a sensitive target.’ And the running round the building again to try and get the angst. We were really out there.”

Ware sighs indulgently: “This is the problem of having an on-site cocaine dealer you see”, and the pair crease up. But other than this kind of pranksterish blow out, fame, it turns out, offered them the chance to pick up the cheque in restaurants, to treat their families, to get some big rounds in down the pub. Chances to capitalize on their success, not just here but in America (‘Let Me Go’ got to number one on the Billboard Dance charts Stateside) in the form of touring were turned down. In fact, before the late 80s they only played a handful of live shows, one of them in their local nightclub in Sheffield, another in Studio 54 in New York.

These decisions, it seems, were taken pragmatically along the lines of, ‘Will we enjoy this? No. Will this take us away from our original concept for the group? Yes. Will commerce come before art? Yes. Well, let’s not do it then…’

Friendship appears to be very important to the pair and it is the subject that comes up the most during the interview. They’re happy to see Chris Watson on the front cover of my copy of WIRE, he’s an old mate from Sheffield and the Cabaret Voltaire days. The whole business with Martyn getting the shove from The Human League only hurt so much because Phil Oakey was his best friend from school… they’re good mates again now. They’ve made friends with some unlikely people along the way, not the least of whom is John Lydon. They both break into peals of laughter at the mention of his name and the recollection of some hectic nights out.

It is rare to meet stars who are happy with their place in the bigger scheme of things. So rare in fact that it’s worth commenting on. And that wasn’t an underhand comment comparing them to Bowie above either. While I love the Thin White Duke, I also love Heaven 17 and I know whose 1984 output I prefer.

Bowie of course, being a man of exquisite taste, was an early doors fan of Martyn Ware’s former band The Human League and was spotted at some of their gigs, declaring them the “future of music”. Both bands would go on, temporarily to be both the future and the futurism of popular music. But in 1980 it was the cold, synthetic, futuristic element of Human League’s sound brought to the table by Ware and fellow synthesist Ian Craig Marsh that was deemed to be holding them back from chart topping success.

Well, by their manager Bob Last at least. In 1980 he took advantage of tensions in the group between Ware and Phil Oakey and engineered a split. This left the still smarting Ware and Craig Marsh to team up with their old mate and Sounds/NME photographer Glenn Gregory to form H17. Ware in particular was determined not to fall by the wayside while the newly popified League were groomed for TOTP glitz. Both bands raced to release their next statement. Heaven 17 with Penthouse And Pavement and The Human League with Dare.

H17’s debut is not just a brilliant British pop album but a truly individual work, subtly subversive, and amazingly prescient; despite it’s innate oddness, when it came out in 1980 it managed to simultaneously predict the first half of the coming decade and satirize a culture which barely even existed. And it is this album which the pair are touring later in the year and why I’m talking to them this afternoon.

On a personal note, I can’t stress how much I loved H17 when I was in school. My friend Philip and I played their first three albums on cassette continuously and obsessively, pouring over the lyrics tempted initially by the glistening pop but hooked in tight by the sheer oddness of them. It was impossible to pin down exactly what they were. It still is, in fact. So while I won’t apologize for the slight fanboy tone of some of my questions I will apologize for just ending up chatting with them and forgetting to ask a handful of questions that I fully meant to ask. (Why is Ian Craig Marsh not part of the tour? Did Anthony Burgess ever hear Heaven 17, and if so what did he think of them? And why does Glenn use that ridiculous Australian accent at the beginning of the remix of And That’s No Lie? “Now listen! Now, I don’t even wanna think about it! Ah just forget about it!” Answers on a postcard please.)

For fans of synth pop and new pop and post punk, which is what I grew up listening to in school, it’s good to see you being presented in the context of these Penthouse And Pavement show instead of one of Tony Denton’s Here & Now 80s package tours.

Glenn Gregory: Yeah. Well, we’ve done both to be honest but this is more true to how we are.

Martyn Ware: We’ve been doing Here & Now tours for quite a while now. We supproted Erasure in a big arena tour and supported Boy George and we’ve been kind of refining our act over a period of 12-years now. Because we only really started performing live in 1988, or something like that. Being the awkward buggers that we are we used to have this dogma about playing live. So we’re still kind of excited by the prospect which is kind of rare for people who have been together for thirty years. But when we came to looking at the 30th anniversary tour, we just thought wouldn’t it be nice to do it thoroughly, contextualize it with the whole B.E.F. thing and make it visually appealing as well.

GG: Me and Martin were in the pub discussing where to take it. Not like an 80s package thing but something else and that’s when it came to us, that it was 30 years since the first album… But the first thing after that was we wanted it to be an artistic thing, not a greatest hits, happy, joyous affair.

MW: Kind of how we would have done it then, when we were angst ridden post punks, post Human League. Full of energy. Full of resentful energy. [laughs]

I was going to ask you about the post punk thing. Obviously in some ways Heaven 17 was clearly pop music from the get go but at the same time with that mixture of funk and socialist/marxist message, subversive messing about with traditional song structures being subverted… did you see yourself as having stuff in common with Gang Of Four and The Pop Group?

MW: Well, we were on the same record label as Gang Of Four and The Fire Engines and people like that. I guess we were bound up with the punk and post punk thing in a way. If you go back to the early days of the Human League we thought it was two things. One, we wanted it to be revolutionary, which I guess it was for the time but also it needed to sound tough, aggressive and daring and a bit rough… Of course when it was time for the music to be mastered in them days, the mastering engineers were all used to working with the Eagles. They were used to working with bands who were smooth and they wanted to iron out all the creases. We didn’t know any better at that point so we didn’t have any option. Early Human League albums and Penthouse and Pavement which have been remastered using more modern techniques, they now sound as we had originally envisioned them. How they should have sounded at the time. So there’s a certain circularity to us finally doing the live show now.

GG: We always had a connection with the more political, more angry, almost punk side but we were also listening to The Jackson Five and a lot of glam. We always had that mix, even before we started making music.

MW: It was quite Sheffield. Well, the North in general is like that but Sheffield in particular is a city of unexpected juxtapositions. Because part of it is good, honest, working class, put a lot of effort into it and it will sound great, craftsmanship and on the other hand, at the time, a desire to escape from the mundanity from unemployment and a lack of prospects. Of course it’s changed now and we’ve obviously done a lot of recontextualizing of it over the years but looking back now that seems to be what was going on. But that wasn’t what was driving us at the time. You just do it at the time. You don’t theorize about it. You just do it. In the fullness of time you can analyze why.

GG: I went back up to Sheffield to take pictures of Joe Jackson for Sounds or NME and met Martin who told me the League was splitting. He said do you fancy forming another band and two days later I was living back up North. Ten days later we’d recorded ‘Fascist Groove Thing’. There was that much fucking energy and enthusiasm and wanting to prove what we could do… For you [Martin] especially!

MW: Yeah, there were certain agendas…

GG: Climbing that mountain as quickly as possible.

MW: Also, Glenn and Ian [Craig-Marsh, original H17 member] were mates. We’d always just hung out if we’d not been in a band we’d still be mates now anyway.

GG: [nods] Absolutely.

Was there a community that you were part of? I mean I hear about these parties that used to go on round at Richard Kirk [Cabaret Voltaire]’s house…

Both: [laughing] Yeah!

GG: Yeah, it was definitely a community and a very close knit one at that.

MW: It wasn’t particularly clique-y though was it? I mean anyone was welcome into it. It wasn’t like ‘Oh, we’re the Pink Ladies’ or whatever.

Who are we talking here? Artery? Clock DVA?

MW: Yeah, well Adi [Newton] from Clock DVA used to be in a pre-Human League band with me and Ian called The Future. And he wanted to do stuff that was more avant garde and we wanted to write more pop music based stuff so that’s why we split up.

GG: I met Adi on the first day of my graphic design course at the art school but he was called Gary Coates and I said to him, ‘Gary. I hate that name Gary.’ And he said, ‘Well, call me whatever you want.’ I said, ‘I’m going to call you Adi.’ And he said, ‘Alright!’ So he was called Adi from then on…

MW: Adi was always into Throbbing Gristle, Aleister Crowley… the darker side of things. And members of his band… we had a good friend called Judd [Steven Turner] from Clock DVA who died of a heroin overdose… it was that darker end of things. We were more interested in this bizarre juxtaposition between banal pop music and electronics and later in H17 it was even more liberating when we could add elements like bass or strings.

So that’s the context of Penthouse And Pavement right there. Do you want to set the scene for us now as well by explaining briefly how you came to leave Human League, Martyn?

MW: Basically there was a band meeting called and I turned up at the studio. Bob Last our manager was there and Phil [Oakey] said, ‘Martyn, we’re throwing you out of the band.’ And I said, ‘I don’t think so, it’s my band!’ [laughs] This all came as a complete shock by the way, even though there had been some tension in the group; it had been a bit like two alpha males locking horns – we’re very similar characters. And we’re mates now by the way. It came as a bombshell to me. Ian had known what was going on behind the scenes for some time and didn’t like it. They assumed that Ian was going to jump to Phil’s camp but when push came to shove he came with me, for which I’m eternally grateful. Bob Last admitted recently, finally, that he manipulated the whole thing because he thought the band was going to split anyway – which it wasn’t. I would never have walked away from it. I would probably still be doing it now.

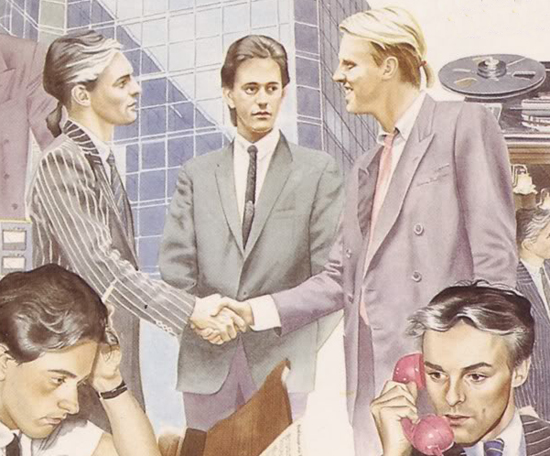

MW: So that was a very hurtful phase and I was determined that something positive should emerge from it. So rather than fighting for the name The Human League and going through a lot of messy legal battles I just decided to start something new and I was fairly confident that with Glenn and Ian’s help… because we were The Human League. We wrote all of the music apart from Phil [Adrian Wright] who wrote the top line melodies on some of the songs. But 50% of it, maybe more, was me and Ian. What was clear was that they wanted to make Phil into a massive pop star and earn lots of money. Which is fine. But we wanted to keep hold of that artistic integrity thing… and also be pop stars! So that meant that we had to do something strange, something unexpected like ‘Facist Groove Thing’. Which as a statement, it didn’t work did it? Because it got banned. It made the mistake of mentioning real people. And the idea that we could incorporate what was in our souls, which at the time was a political awareness. For example, we were fans of Gil Scott Heron, for instance. We were very influenced by black acts from America at the time. Curtis Mayfield, Parliament, Funkadelic, social activist. We had a certain empathy for what they were singing about… Chocolate City and that. It was almost as if we were the blacks of Sheffield… [laughs] It sounds ridiculous now! But that’s the way we were thinking. We felt like we were the underclass. But as soon as Phil started going on about him getting rid of the unaesthetic part of the group after the split, well that just wound me up. That was it. From that moment on we were determined that aesthetically we should be on the high ground. Not only in how we presented ourselves artistically but in terms of style, hence the suits, hence looking immaculate, hence spending a lot of money on videos with really good directors that we could be really proud of and could serve lots of different territories for us. It was a brand new world for us. It was almost like a race.

GG: It felt like a race to us. We were writing Penthouse And Pavement in the same recording space in Sheffield that they were writing Dare. There wasn’t enough room for everybody to work and write at the same time, so we just decided to do shifts. We did it two week shifts, one band on days and the other on nights, and at the end of the fortnight we’d change over. And you’d come in and find a bit of ‘Sound Of The Crowd’ on a tape, so we’d listen to that! [laughs] And they’d find a bit of ‘Fascist Groove Thing’ and be going ‘What the fuck’s this?!’ It did feel like a race. It was exciting.

Where did B.E.F. [British Electronic Foundation] come into it? I always get confused about the time line…

MW: Well, this was part of Bob Last’s masterplan. As soon as he provoked the split, he whisked me and my wife away to Edinburgh, to his home. I was devastated. Phil was my oldest and closest friend from school and I was heartbroken. So he whisked me off to Edinburgh to stay with him and he comes out with it, ‘I think with your talents, you should form a production company.’ He already had it all planned. He told me that he would negotiate a deal with Virgin so I could work with lots of different acts. It was a great idea but we didn’t have a name. I wanted something really portentous… something really corporate. So we actually did sign a contract with Virgin as B.E.F. saying – and this is utterly ridiculous – that we were allowed to present them with up to six albums a year. They’d finance the recording of it and we’d get a certain amount of advance for each one. And the first one of these projects was Heaven 17. So at the same time I was making Penthouse And Pavement I was also recording Music Of Quality And Distinction with a load of famous lead singers and it was kind of a manifesto for electronic music.

So it was parallel?

GG: It was parallel. I remember we were working on tracks in between. We’d do ‘Facist Groove thing’ then we’d do ‘Anyone Who Had A Heart’ next.

MW: It was like a crash course in how to do cover versions. I mean with The Human League we’d already done ‘You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling’ on the first album…

That whole concept was very ahead of the curve for the time. Later on it would become very normal for the Pet Shop Boys to work with Dusty Springfield or KLF to record with Tammy Wynette…

GG: It wasn’t normal at all at that time, no.

I guess a lot of the stars were… well, Gary Glitter’s stock hadn’t quite reached it’s nadir but, certainly Tina Turner’s had.

MW: We’d already arranged for James Brown to do ‘Ball Of Confusion’. We’d booked the studio in Atlanta and the day before we were due to fly out, his lawyer rang up and said, ‘We want three points on the whole album’, and we said, ‘Well, you can fuck off! It’s not going to happen!’ We were despairing when the Head Of Finance at Virgin said, ‘I know Tina Turner and I’m on my way to LA.’ I’d just been to see her doing ‘Proud Mary’ at The Venue, a real chicken in a basket show. I thought it was fantastic. I mean I’m a big fan of ‘River Deep, Mountain High’, it’s one of the greatest tracks ever. So I thought of her to replace James Brown. When she got to the studio it was the classic thing of, ‘Where’s the band?’ And I pointed to the Fairight and said, ‘It’s there!’ Ha ha!

Who made the biggest impression on you with their larger than life behaviour?

MW: Gary Glitter.

GG: Gary Glitter was pretty out there. We had the Glitter Band in there with Gary Glitter and it was the first time those two had ever recorded together to make a record. It was Mike Leander who played all the instruments. They made their own records and he made his own records but they never recorded together.

I like the Glitter Band.

MW: Yeah, the Glitter Band were great! I remember Gary Glitter took us to his favourite Indian restaurant which was in the basement of a building in Knightsbridge. He was completely off his nut and after we went down the stairs, instead of walking down, he fell. Literally he fell head over heels, somersaulted and landed on his feet at the bottom and went, ‘Da da!’ But then instead of getting a table, he insisted on taking us into the kitchen to meet all the chefs. But he was off his nut.

GG: We were in the studio with him one night with him and I was going out to a club. I said that I was going and he pulled me to one side and said, ‘I tell you what, bring me some girls back here.’ And like you say, he wasn’t at his lowest point given how bad it got but neither was he at the pinnacle of his career either. I said, ‘Gary… it doesn’t really work like that any more.’ I wasn’t going to start trawling round the Wag club, ‘Hello. Do you want to come back with me and meet Gary Glitter?’ [laughs and shakes head]

I was listening to Penthouse And Pavement on the way here and you can forget how hectic ‘Facist Groove Thang’ is. I mean it’s as fast as some thrash metal.

MW: Yeah, it’s about 157 bpm. Up until that point, dance music had only really gone up to around 135 bpm with Sylvester’s ‘You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)’ [1978].

GG: Yeah, it’s 152bpm. And it is fast! Which makes it all the more incredible that John Wilson did that incredible bass solo on it.

So it was quite a militant statement to start proceedings with. And the genesis was pretty quick you say?

GG: Yeah. It was the first thing we wrote. It was originally called ‘Brothers And Sisters How Much Longer Must We Tolerate This Fascist Groove Thing?’ [both laugh]

GG: Yeah, because if you take every other lyric away you’re just left with a potted history of fascism in Europe! [laughs] And the other half is disco rambling!

But it’s loads easier to accept or to take on board a message when it’s not one of Chumbawamba telling you off… if it’s a bit more surreal… if it’s a bit more mysterious…

GG: Well, that was always our intention.

And it’s not like you were operating at a time when being told off by Lefties in the format of a song was a particularly uncommon thing. I mean this was at the height of Red Wedge.

MW: Well, we were members of Red Wedge.

GG: There was a lot of it going on.

MW: Well we were the opposite to, say, Billy Bragg, who took a very literal, these are my beliefs, you should believe like I believe line. But it wasn’t just the coding of the lyrics but the fact that it came packaged as pop music. So it was delivered as one thing but if you delve into it, peel back a few layers, you find it’s also something else. Well, that’s what we tried to do anyway.

GG: As Martyn alluded to earlier it was always the three of us writing lyrics. We would all have piles of paper on the floor in front of us, all gradually getting mashed up. And often the song would mean a different thing to different members until about two thirds of the way through when we’d all go, ‘Ah! Right!’

MW: Or even three months later, it might occur to you what the song was about. I remember we had a day left in the studio to write ‘Soul Warfare’ and we were on the roof writing lyrics. We were in that stream of consciousness mode where you just don’t know what it means anymore but you’re just writing stuff down. It just flows.

That’s interesting. I was listening to ‘Lady Hex And Mr Ice’ today and obviously the vocals are done in a fairly Frank Sinatra/show tune kind of way but I realised that the actual music and lyrics made me think of Underworld, who are another band who obviously went on to use stream of conscisouness lyrics, allowing meaning to coalesce round the various phrases that flow from Karl Hyde’s notebook…

Both: Yeah.

Penthouse And Pavement was very successful in predicting a lot of stuff about the 80s. The many bad things and, dare I say it, the one or two good things, that happened during the Thatcher administration. It parodied newly emerging classes before they’d barely existed. It used a new language of nuclear war as a metaphor for love affair. Or the free market as a metaphor for personal relationships. And vice versa…

MW: Well, on one level we acknowledged that love is the most popular subject matter for pop music, it’s just that we didn’t want to do that. In fact we had a list of words that we banned ourselves from using.

GG: And it was ever growing. If we ever found we were leaning on a word too much we banned ourselves from using it again. There’s no love on the first three albums. Then ‘dream’ was another one. ‘Game’ was another.

MW: We were always fighting against the banal I suppose. Any way we could make a metaphor using other structures that were around at the time. We found it interesting and apposite at the time. I mean, ‘I’m Your Money’ for example. I still think that’s funny now. It’s a very good analogy. And ‘Let’s All Make A Bomb’ I guess is quite clever. People interpreted it as let’s all make a lot of money, which is not what it meant at all. It was about mutually assured destruction and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. You’d never put those in the lyrics but that was the philosophical basis we were working from when we were writing it. If you take a cooking analogy, we were reducing a stock pot of ideas down to a [puts on exaggerated, pretentious accent] jus. A jus, I tell you! I need some more coffee…

So right from the get go you joined the auspicious ranks of the Sex Pistols [‘God Save The Queen’] and George Formby [‘When I’m Cleaning Windows’] in having a single banned.

GG: Yeah. That was a bit of a blow that because we loved that single. We thought it was a really bold statement of how we wanted to be seen and the press loved it. Record Mirror, NME, it was single of the week. We were overjoyed because they got it. But then…

MW: Then we got a panicky phone call from Virgin going ‘Oh my God! They’ve banned it! You’ve got to do a different version now!’ We actually went into the studio and changed the lyrics to the only thing we could think of. So there are 100 white labels out there with the line, “We don’t need that Axis groove thang” instead!

[both start laughing]

**I fucking hate Mike Read. He symbolizes everything that was wrong with Radio 1 in the 1980s.

And is probably still wrong with it now. Creepy old out and proud Conservatives with Cliff Richard haircuts hanging round with teenage girls. It’s just not right. It wasn’t enough that he ruined the Icicle Works’ entire career by saying that he had sex to ‘Love Is A Wonderful Colour’…**

MW: Oh my God!

Of course you were feted elsewhere though. Did it ring warning bells with you how much you were feted? Or did you enjoy the attention of people like Paul Morley, Simon Reynolds and David Stubbs and the focus on the so-called new pop movement?

GG: Paul always got stuff straight away. To be honest, you were grateful having someone like that in your corner. And I guess at the time you wouldn’t be wary of it. I think looking back you might think that you were picked up and put in a box that wasn’t of your choosing. You think that you’re not in a box at the time but of course you are…

MW: The more disturbing box was the whole new romantic box. We had nothing to do with that movement.

You weren’t that and you weren’t really synth pop either.

GG: Not ultimately no. I guess we were closer to new wave. New wave in Europe and America would have covered what we did but that phrase was quickly derided over here.

The threat of nuclear war looms over the album. Retrospectively we tend to think of Sheffield and nuclear war in close terms because of the sheer brilliance of Threads but before that the link was there in the popular consciousness because of you. How real did the threat feel to you? Because it was something you were still writing about come How Men Are on ‘Five Minutes to Midnight’ and ‘Sunset Now!’

GG: It was incredibly real. They were showing that fucking stupid Protect And Survive film on TV all the time. It was part of your daily life.

MW: It was the zeitgeist. You look at that dream sequence in Terminator 2 or whatever were the whole of Manhattan is destroyed…

GG: I remember you having that vivid dream of a tower melting and the sky turning red…

MW: It obsessed everyone who was thinking.

‘Five Minutes To Midnight’ is my favourite song about a nuclear bomb going off. It captures the utter modernity of the sense of that much civilization getting wiped out in one fell swoop… without being too hysterical. And it’s probably quite easy to get hysterical while singing about nuclear armageddon.

MW: It didn’t seem fanciful.

GG: It seemed very fucking probable.

MW: I was just annoyed because we were having such a great time! I thought, ‘Why would the powers that be end it all?’! That’s what it felt like in a very simplistic way. And also how stupid they were. Who could believe in mutually assured destruction? What was going through their minds? In the same way that I can’t believe that we still fund Trident. So we’re going to launch a nuclear strike on someone from the Atlantic or the Arctic Circle are we? Er, and what’s going to stop them from retaliating and wiping out the UK? It’s just insane! The whole premise of it is insane. Everyone knows it’s economically driven. It’s not driven by any ideas of safety or protecting one’s borders, it’s just purely because of Aerospace jobs. End of story.

It’s kind of depressing listening to Penthouse And Pavement and realising how little things have changed. I was reading a H17 interview from 1980 this morning and Martyn’s calling for the banks to be nationalized. I mean fuck me, and here we still are…

[both laugh]

MW: You know, it’s funny. That was one of Tony Benn’s primary things at the time and we’re there but not in the way he envisioned it at all.

So now I have to bring up the elephant in the room, which is the Penthouse and Pavement photo shoot… Now Glenn, I’ve got to say that the combination of a turtle neck, a beret and a baseball bat… even as a callow youth I didn’t feel that threatened…

GG: [laughing] I’m not sure if it was supposed to be threatening… The Daily Express asked me to do an article called Why I Love This Photograph, so I chose that picture and I wrote a really witty and concise piece about how it came about and they came back to me and said, ‘We don’t want to use it… it’s too racy.’ Really?!

[Martyn cracks up]

Well, there is the Amyl Biker stood in the middle but it’s still hardly X-rated violence…

MW: It was more inspired by The Warriors. We didn’t want it to be too grimy. We wanted it to be a bit more comic book. We’d done the penthouse pictures in the suits and we needed some images to juxtapose against them. I think the most disturbing one in that is Ian because they’re his own clothes!

[Glenn laughs]

He’s wearing headphones! I’m terrified! So John Wilson, your guitar savant, how old was he when you started working with him?

GG: 17. Pretty early on we’d recorded ‘Facist Groove Thang’ and the backing track was down and we’d got this gap in the middle – a standard middle eight gap – and Martyn said, ‘Why don’t we do something really stupid like have a disco bass solo.’ We didn’t know any bass players who could do any more than play rubbish one note bass lines. At the time to get some money together I was working as a stage hand at the Crucible Theatre just doing the panto and shifting scenery. I asked in the green room if anyone played bass and this really quiet, nice guy called John Wilson put his hand up and said he played a bit. I said, ‘Brilliant. At lunch time can we go to yours, get your bass and you can come to the studio and play it.’ We got the bus to his, picked up his bass came to the studio and we recorded it in one take. He’s left handed but hadn’t restrung the bass, just learned how to play it upside down. He said, ‘Is that OK? Because I don’t usually play bass… I’m more of a rhythm guitar player.’ And we said, ‘Really? Can we go back to your house and get your rhythm guitar?’

[both laugh]

MW: I mean we’ve got a brilliant bass player for this tour coming up but he doesn’t play it exactly the same. I think it’s got something to do with John’s bass being upside down… so there are things about that bass part that you just can’t play in a conventional way. It was fate us meeting John like that.

So after Penthouse And Pavement you started having very big hits over here and around the world as well. Now, I know not everyone enjoys it but how was it for you when you became bona fide pop stars?

GG: Fantastic. I think part of it was that we weren’t really being pop stars. We were still running with the same people that we were running with when we were younger. All it meant for us was that we could buy our friends more drink and more food than we could previously.

MW: Yeah, it meant that we had full on party time for five years. It was good. We were in a good position because we were still in the ascendancy when we did The Luxury Gap. The record company had good faith in us and we still had a lot of resourcefulness left so they pretty much said we could have whatever we wanted to record the next album. And we had a deal which said that they would have no say in the creative side of things.

I guess the younger generation in this country will know you primarily for ‘Temptation’ as a radio staple and maybe because of the La Roux collaboration but that wasn’t your big hit in America was it? That was ‘Let Me Go’. What was it like having success Stateside?

GG: Obviously we just never translated into an enormous success because we didn’t play live and you have to go and do that. I was speaking to La Roux recently and they’re in the middle of doing that… And I look at Ellie and think, ‘Thank fuck we never had to do that!’

MW: We saw other people emerging from our scene who decided to go down that route and they were successful but it destroyed them as well. Simple Minds went down that stadium rock route but they couldn’t maintain that energy or interest.

GG: ‘Let Me Go’ was the hit in America. ‘Temptation’ was never released in America. ‘Let Me Go’ got to number one in the dance charts and we did actually go over and perform in Studio 54. And John Lydon went to see us play there. And I didn’t know that until many years afterwards.

MW: We’re mates with John now. He told us that he’d come to see us and we were like, ‘Fuck off!’ You wouldn’t think that he would be a Heaven 17 fan but he loves our stuff.

GG: We’ve had some funny nights with him.

MW: [shivers] You can go into detox just thinking about it!

Who was the most star-like star you bumped into on Top Of The Pops?

GG: Elvis Costello once accosted me backstage because I’d given his single a bad review once in Melody Maker. He asked me why I’d done it and I said it was because I didn’t fucking like it! [laughs] I wasn’t picking on him but he just didn’t get it!

MW: Jimmy Saville was just bloody wrong!

GG: [laughing] He was amazing! And Tony Blackburn. He looked like an animatronic. I actually got really shirty with one of them the first time we did it. We were on doing ‘Play To Win’ and I lost my temper with Simon Bates. They were stood behind him clapping but they weren’t doing it properly so he was having a go at them, really shouting at them. And I was like, ‘Excuse me! There’s no bloody need to talk to people like that!’ It was a bit ‘Oooooh!’ [mimes handbags]

Bar John Peel, they were like the Tory cabinet then weren’t they? By the late 80s you had acid house, hip hop, bands like the Mary Chain, the Pixies, Sonic Youth, the Stone Roses and the Happy Mondays… and the radio at lunch time you’d have Dave Lee Travis, the hairy cornflake playing ‘Hotel California’ by the Eagles. Insane!

MW: You really had to play the game back then to get on the radio. They really made you jump through some hoops.

It’s worth pointing out I guess that there was a lot more at stake in the 80s. That even some of the bands who would get played on John Peel’s show would still probably sell a lot of records.

MW: Yeah, it’s true. And it wasn’t 100% play listed then either. The shows would have their own producers and would sometimes just drop records because they felt like it. I think that was a healthy thing. Now it’s all completely computerized. So even if Dave Lee Travis did play ‘Hotel California’, at least it was because he wanted to.

Heaven 17’s 30th Anniversary Penthouse And Pavement Tour starts November 22nd.

Click here for ticket details.

November

22: Edinburgh HMV Picture House

23: Glasgow O2 ABC

25: Manchester Ritz

26: Birmingham HMV Institute

28: Lonon HMV Forum

29: Oxford O2 Academy

30: Brighton Corn Exchange

December

01: Bristol O2 Academy