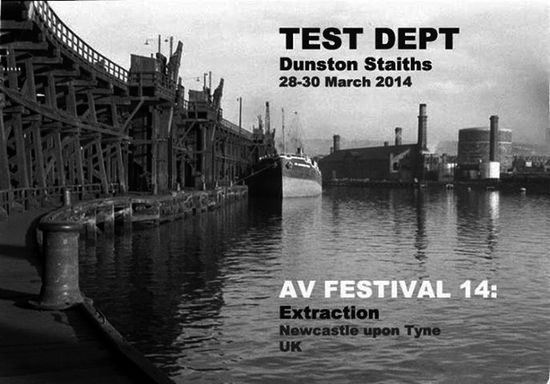

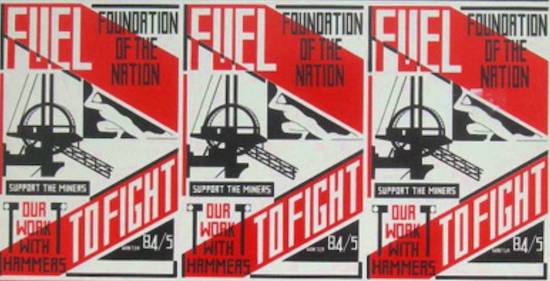

During the 1980s, Test Dept were one of the few second wave industrial groups to take the rattle, noise and provocation of industrial music into a political sphere, rather than yomping around in dank nightclubs in a pair of big boots. They were pioneers of multimedia live installations that did far more than combining music and film – in their hands, the spaces in which they appeared became integral to the performance, clobbered and battered and attacked to generate sound. Given the collapsing state of British industry during the period, this inevitably had a political impact, and in 1984 the group collaborated with the South Wales Striking Miners Choir for fundraising LP Shoulder To Shoulder. Thirty years later, founder members Paul Jamrozy and Graham Cunnington are reconvening for the 2014 AV Festival, at which they’ll be conducting a major Test Dept installation at Dunston Staithes. The theme of this year’s festival (the 2012 instalment is reviewed here) is Extraction, and involves artistic responses to the history and legacy of the North East’s coal industry, as well as examinations of post colonialism and environmental damage.

Dunston Staithes are a gigantic, dilapidated wooden structure in the River Tyne where, during the peak of the Northumbria coalfields, ships would be loaded with thousands of tonnes of the black stuff for export or transportation to steelworks and other industrial sites around the British coast. The infamous Paul Smith of Blast First records suggested that it might be timely to commemorate the Strike at AV Festival via the involvement of Test Dept, who handily enough were currently working to invigorate their archive for a book and a series of Test Dept Redux electronic remixes of their past work. Further contemporary resonance could be heard in their appearance at the Rich Mix Cinema in London a few weeks ago, where, at a fundraiser for a film version of Seumas Milne’s book about the Miners’ Strike, The Enemy Within, they spoke and DJ-d a collage of contemporary techno artists, including tQ favourite Perc, brought together with sound samples from the time.

What will the Dunston Staithes installation consist of?

Paul Jamrozy: It’s an audio visual, lighting, sonic installation. In effect the Staithes are the star of the show, because it’s the largest wooden structure in Europe, and it’s the only remaining sign of the industrial heritage along the Tyne. When you think of Newcastle as an industrial city and there’s nothing there to show its past, it’s odd how it it’s been totally erased. But the Staithes are in such a state, we looked at various possibilities of live stuff, how it could work, but the reality is the Staithes aren’t in a safe enough condition, in terms of putting in enough infrastructure to make a live thing work. There are a lot of health and safety issues, so in the end we thought it best it we work towards an installation.

Graham Cunnington: The audience will be on boats, there’ll be sound and film and light, and it’s also about the journey going there and back.

Can you tell us about the history of the Staithes?

PJ: The original wood was imported from Canada to build them. There used to be toll gates down the river, so in order to be competitive they thought, "Sod that, we’re not paying their tolls, we’ll bring it cross country by train, import all this wood from Canada and build our own staithe". It was a mad scheme idea, and I suppose in those days people did have mad scheme ideas like that, and it did the job, and did it well, because the structure’s lasted all this time.

GC: The key thing is that it’s this monument to all the industry on the Tyne, and through that to the coal industry. The coal drove the industry on the Tyne, all the steel, which then fed the shipbuilding industries and the railways.

PJ: The railways started up there. Stephenson started the railways to shift coal.

What technical challenges have their been?

GC: We came across some in the design stage, working out how it could be viewed from a boat, all the angles and the tides, and in the final week before the show we’ll probably come across some more.

PJ: Even just for rigging there are only certain parts of the stage that you can physically get on, that are safe. There are lots of limitations and restrictions on doing it. We’ve been working with Martin [Hulse] from the Tyne & Wear Trust, and they’ve raised a lot of the money for the event to promote the Staithes. They know them inside out and what’s possible. It’s a challenge, but it’s an interesting challenge.

Are you projecting work from Test Dept’s history? Will you be using material from Shoulder To Shoulder?

PJ: It’s to celebrate the strike, and our engagement with the miners was during the strike, so a lot of that stuff’s relevant.

GC: It’s introducing the Staithes. The strange thing is that they’re there in the river, but they’ve been left to dilapidate a bit, they’re ignored. There are a lot of people who love them, you can see them from the bridges, but a lot of people don’t know what they are. It’s bringing them back to life, introducing their history, bringing in the connection with the coal mining industry, and then onto the connection to the strike and our connection with it as well.

When you were working in the 80s, a lot of the industries were only recently closed. With the anniversary of the strike, do you get concerned people have forgotten these things?

PJ: I think for the younger generation these things have been erased, so they don’t have the same awareness. But for the people who took part in it and lived through it, it’s certainly not forgotten, and bringing up the 30 years of the strike brings it to the fore. People are still very bitter, there’s a lot of anger. I think it’s important to engage with that. Seumas Milne is bringing out the new Enemy Within book, and there’s some stuff coming out with the Freedom Of Information Act, there are people still looking for some truth and justice to come out of it, with Orgreave and how the strike was policed. So that’s why it’s become important for this year, more than maybe 10 years ago. For the younger people it’s important that there is a connection with the past, that it’s not completely erased and that people understand where they come from. Coal and the North East – it is a very important part of their culture.

GD: The Staithes being the only monument to that, not just on the river but anywhere…

PJ: There’s the mining museum, there’s Beamish, there’s the Durham miners’ gala, which is a big event, in the 50s there were 300,000 people turning up to these events. They nearly died out in the post-strike years, but it’s become reinvigorated and become more international.

The installation will have a strong resonance with what’s happening under the current government, and how that sort of politics operates.

GC: The same things are coming out of their mouths. But it’s also the fact that the Miners’ Strike was the beginning of this situation of neoliberal, rampant free market capitalism, where there isn’t any protection, there’s nothing to stop them, because it’s accepted as the norm. The Miners’ Strike was the start of that, because Thatcher knew that she had to defeat the unions to do all of that, she had to get the miners out of the way. It was the kicking in of the door to bringing all of that in here, to the current situation we’re in.

PJ: It was also the first signs of the militarisation of the police force in a way that is now just accepted: whether you’re a pensioner or a student you’re going to come across against people in full riot gear ready to attack you at the slightest excuse. That all became normalised during the Miners’ Strike.

GC: And as we’re hearing now, well it was widely known then but it’s being more generally portrayed in the media, the surveillance, that widespread public surveillance started there. We didn’t have any internet but phones were tapped, spies were infiltrated in, there was a huge amount of it going on. Our own phones, we believe, were tapped. Obviously it was going on a bit before that, but mass public surveillance became more widespread then.

You and Laibach, who you played with during the 80s, are coming back now; do you find there’s not much politics among younger avant-garde or ‘noise’ groups?

GC: I think that’s true. Politics is a dirty word, and people don’t want to get involved in the same way.

PJ: I think it was a fairly dirty word back then. People might look at the Second World War, and Nazism and totalitarianism in general, but in terms of engaging with contemporary politics it was quite unfashionable then as well as now, amongst the avant-garde musicians. People may have touched on it, but it wasn’t very from many people. I think it’s interesting now because there’s the social media and during the Strike the State had all the power. I think if they’d had social media then possibly the Strike might have been more successful because of more coordination of different people around the country. It’s quite interesting.

How do you see the future for Test Dept? Will there be more installations and activity?

PJ: A lot of people have expectations about who Test Dept are and what they represent, and they have to appreciate that the high energy of what we were doing back in our heyday was quite physically damaging for us then, and being slightly more mature, that physicality would be life-threatening. So it’s a challenge to actually try and capture that spirit and that energy in rework it in less physical ways, or get other people involved, that could be interesting. For ourselves, playing 150 beats per minute and wielding a sledgehammer is possibly slightly physically beyond us.

The AV Festival is happening throughout March at venues across Newcastle and the North East. For more information and tickets, please visit the AV Festival Website