Photograph by kind permission of The Wire/Leon Chew

Newcastle took its time to get where it did today. Somewhere under a red concrete slab outside the Miner’s Institute on Westgate Road lies Hadrian’s Wall, which divided wilderness and the savage magic of the Celts from the Roman idea of civilisation. Now civilization marks this with a plaque on the wall, and a retired miner tells me of a plan to uncover the ancient foundations for public view.

Newcastle is a city sliding off itself into the waters of the Tyne, which finds its source high on the Northumberland uplands, one of the most sparsely inhabited places in the United Kingdom. It’s also one of those few cities where, standing in the centre, you can see outside, to distant hilltops, trees and hilltops clearly visible. The railway slices through the centre of the city, Victorian viaducts just yards from the walls of the Norman castle keep, built by Robert Curthose. Son of William the Conqueror, his surname is thought to have meant "short trouser".

"Well, here I am in Newcastle. I had then to consider the next move. The afternoon was nearly done. It was raining, though not hard, and the whole city seemed a black steaming mass." JB Priestly – An English Journey, 1934

"Aye, you liked it. You came on a sunny day." – Friend of the Quietus Geordie Mark, March 18, 2012.

Dividing Newcastle from Gateshead, and crossed by seven spectacular, diverse bridges, is the River Tyne. Down these waters from rural Cherryburn in the late summer of 1767 in came one of Newcastle’s more eccentric, even mystic sons. Thomas Bewick was a pioneering engraver and compiler of some of the first taxonomical records of bird life, in his History Of British Birds, published in 1797 (Land Birds) and 1804 (Water Birds). Controversially in his time, Bewick’s understanding of nature had led him to Deism, believing that the Biblical concept of original sin held people back from happiness, and did not "come within the scope of either rationality or justice." His knowledge of engraving giving him a perfect sense for the use of intricacy, he was one of the first to use the fingerprint as an identifying mark. His final woodcut, called Waiting For Death, was of a horse in a wild rural scene, suggesting a spirit about to become part of nature itself. A rather brutal tower block, Bewick Court, now rises above the centre of the city.

"Does death come alone / or with eager reinforcements / death is centrifugal / decadent and symmetrical / angels are mathematical / angels are bestial / man is the animal… Holy holy holy / holy holy" Coil – ‘Fire Of The Mind’

The curatorial theme of this year’s AV Festival, As Slow As Possible, sees a stunning collection of events taking place in Newcastle and the surrounding area over the month of March, with the two music-focussed weekends occurring across the spring equinox. Its myriad installations, events, talks, film screenings and walks exude the quiet confidence that you sense in Newcastle in 2012. It’s as if the local pride expressed in the many statues of men whose now-dead industries built the city has been transferred into new spaces, new forms, a new democratic creativity. After a bleak late 20th century for the region, perhaps it is now turning a corner.

There’s physical evidence for that, of course, right on the banks of the Tyne. In the Baltic Centre, over in Gateshead, is On Kawara’s One Million Years installation. The Japanese artist created two volumes of text, Past (years 998,031 BC to 1969 AD) and Future (1993 AD to 1,001,992 AD). In the sterile white room, two gallery invigilators read off a year at a time, wearily ticking off each 365 days as it is, an insignificant itch in time.

The L-shaped Newcastle Civic Centre across the Millennium Bridge and up the hill is a rare example of postwar architectural intelligence designed by local city architect George Kenyon. A rabbit (they have urban bunnies in Newcastle) hops though a flower bed next to where the emo teens sit. Under a part of the building, the concrete pillars of which lend an the air of a future sacred place, is Susan Stenger’s The Structures Of Everyday Life: Full Circle sound piece. Though it marks the birth and death of John Cage, it’s detached from that context for many who stumble across it. Six speakers are arranged in a circle with one in the middle, and they transmit a deep and calming drone. Some come into the circle by mistake and are caught short for a ponder, others pass through bemused. As you walk back out into the city and traffic, ears strain for the calm. "Me fucking laces," screams a girl heading for the boozers of the city’s Bigg Market, nearly going flying into a speaker.

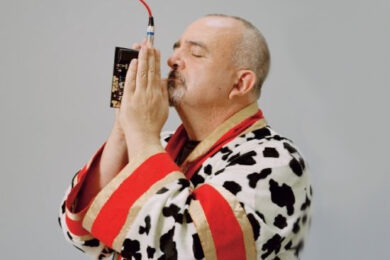

Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson died (on November 24th, 2010) before he was able to complete his commission for this year’s AV Festival. After his passing, Throbbing Gristle manager and Blast First Records’ Paul Smith and others felt it was appropriate to attempt to pick up some of the threads and turn what would have been Sleazy’s own performance into something of a memorial, under the title Wishful Thinking: In Remembrance of Peter Christopherson. These, as Smith puts it, would pick up on thoughts and discussions that Sleazy had already started to set down, to create "sketches in sound and light, nuances, essences, loose threads, glimpsed from the peripheral vision."

"If I think on you a while dear friend / All losses are restored / and sorrows end" Shakespeare’s Sonnet 30, from Derek Jarman’s The Angelic Conversation screened at Wishful Thinking

Silence is ushered in by the ting of a cymbal. Tibetan prayer bowls and bowed objects are all that’s audible in the hushed Tyneside Theatre. Attila Csihar (Mayhem, Sunn O)))) sits on the stage behind a candlelit table on which rest a mixer and various effects units. A sound recording of the interior of Durham Cathedral, made by Chris Watson, begins to fill the room.

"It came to my attention that Peter Martin Christopherson was (nearly) a local boy who spent his formative years growing up in nearby Durham. Durham Cathedral was a brooding presence over his young adulthood that offered his young mind little or no sanctuary but a strong memory of a transporting boys choir. The work was originally… to be staged at Durham Cathedral, in which he could revisit the ghosts of his adolescent frustrations, his subsequent triumphant blossoming, and his launch pad into the artistic world." – Paul Smith, writing in the Wishful Thinking programme notes.

A master of the recording and documentation of space – as was Sleazy, in both Coil and Throbbing Gristle – Watson beautifully utilises Durham Cathedral’s ability to magnify sound, capturing draughts in corners, the odd muttered voice, a rattle of metal that might suggest the profane as well as the sacred. When Attila Csihar lifts the microphone to his mouth and begins to chant, the physical reaction of all present is tangible. Considering that such a response to music is often provoked by the use of highly-amplified digital or analogue sound (something Christopherson and Throbbing Gristle understood so well), to hear such force from lungs and loops alone has an intense impact.

Behind Csihar are projections of collages and images by the visual artist Alex Rose. There’s a skull with what might be shells for its eyes, photographs of young boys in various states of undress, another skull chewing on a slab of rock. The changing of each slide is punctuated by the rattle-and-thunk foley recording of an old-fashioned projector. As well as being a reminder of Sleazy’s visual talents, the rhythm gives a sense of sacred punctuation, the thumbing of a prayer bead, a ritual aid to our thoughts.

Derek Jarman’s A Journey To Avebury, screened as part of Wishful Thinking is a complex meditation on the ancient magic monuments of England in the man-made landscape of the southern uplands, where copses of trees stand out eerily on distant hills, and the dark entrances to abandoned World War Two pillboxes are to be found in the hedgerows. Coil’s geiger counter soundtrack amplifies the glowing unreality of Jarman’s warm, yellow filters.

It must have been a strange kind of burden for Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti to take up the "final report" of Throbbing Gristle, a take on Nico’s 1971 album Desertshore, first conceived of by Sleazy back in 2006. I don’t think anyone in the audience quite knows what to expect they’ll have done with it, given that in the hands of this group the conventional has, over three decades, been given rather short shrift.

What happens is a quite remarkable set of songs, a repurposing of Nico’s maudlin, scraping sorrow into the deep mind-massaging electronics that characterized later live work by Throbbing Gristle, X-TG and Carter Tutti, arguably even Coil’s Ape Of Naples. Sleazy is present as a memory in the projected image of the Norfolk beach where he’d enjoy some seaside chips with Chris & Cosey on trips back to England from his adopted home of Thailand. Each track begins with sound materials left behind by Sleazy as part of his initial work on Desertshore. Tutti says these were then used by herself and Carter after Sleazy’s passing as the genesis for work on the Nico covers. ‘Abschied’ has vocals by Einsturzende Neubauten’s Blixa Bargeld, then ‘Le Petit Chevalier’ is dark and heavy, dense subterranean bass and Gasper Noe’s vocals cauterised by static and sounding barely human, a sort of mordant techno gasp. Sung live by Cosey herself, the wounded distraction of ‘My Only Child’ becomes brightly euphoric, the deep crashing of the music against the vocals a comforting, pop embrace. Most splendid of all is ‘Janitor Of Lunacy’, one of the most intense songs ever written by Nico. Sung by Antony Hegarty over Cosey’s cornet and steel-on-strings guitar, it takes on an entirely new life, very urban, nocturnal, erotic, very… well, sleazy.

They conclude not with a Nico track but an original composition. This is, says Cosey Fanni Tutti, "an au revoir, an adieu to Sleazy that features the many voices of those that were close to him." Over a more abstract soundtrack these voices all repeat the same line, "Meet me on the desert shore" rising and falling, as if they were members of a choir for that empty cathedral sketched by Chris Watson. It’s a lovely moment. The summing up of Throbbing Gristle’s ‘final report’ might well suggest that, over 30 years, the supposed nihilism of this group has been perhaps overstated. That was merely one element of their comprehensive and provocative embrace of the entirety of the human experience.

This performance, these sounds and these ideas now furthered under the Throbbing Gristle name in the absence of Sleazy, create a portrait of who he was (and always will be): the questing spirit voice and adventurer, a great wit, a transgressive explorer of what writer Rob Young, earlier in the day, had described as a kind of English reverse.

Peter Christopherson, a wrecker of civilisation? Hardly, civilisation is perfectly capable of wrecking itself (the midnight streets outside the Tyneside Cinema are evidence enough for that) on seas of booze and puke, the hard rocks of idiotic sex, the general fog of political complacency and its twin, cultural mundanity. By imagining an England both ancient and new, a more sensual and thoughtful place, his art offered a paradoxically slower, more nurturing alternative. This weekend in Newcastle proved that these embers shall and can never be extinguished, and remain for all who take the time to engage. In this slow world, Peter Sleazy Christopherson lives on.

"Remember we are all only temporary curators of our present bodies, which will all decay, sooner or later. In a hundred years or so ALL the humans currently alive will have died. I take great comfort in knowing, with certainty, that thing that makes us special, able to enrich our own lives and those of others, will not cease when our bodies do, but will be just starting and new (and hopefully even better) adventure… If we don’t get to meet in this Life, maybe in the next you can buy me a beer!" Peter Christopherson, writing in the Quietus comments section, July 31st 2010.