For fans, free jazz is the most beautiful and liberatory music there is, yet the genre can be a step too far for many. With its unconventional approach to tonality, harmony and rhythm, free jazz can be difficult to get a hold on as a listener. Yet as with reading James Joyce’s Ulysses, the best approach is to just go with the flow and not to worry too much about “understanding” what’s going on. Before long, you realise the music isn’t so much “freeform” as creating its own forms, pulling them apart and recombining them in real time. The music can have melodies and grooves, but it takes them places. It can be cacophonous, but it can also be meditative, eerie, absurd and beautiful.

In this age of digital abundance, the music is easier to access than ever before, yet the sheer volume of it can be daunting. Where to begin? There are already a number of fine books to help you navigate the territory such as Val Wilmer’s As Serious As Your Life, John Litweiler’s The Freedom Principle, Derek Bailey’s Improvisation, David Toop’s Into The Maelstrom, and John Corbett’s A Listener’s Guide To Free Improvisation. Recently Byron Coley, Mats Gustafsson and Thurston Moore stepped up with Now Jazz Now, a monumental guide to 100 essential free jazz and improvisatory recordings from 1960 to 1980.

Aimed at newcomers and partisans alike, Now Jazz Now is testament to Moore, Coley and Gustafsson’s deep knowledge and passion for the music. Self-confessed discaholics, the three friends have spent years searching for the rarest jazz and improvisation releases, yet they’ve always shared the love. Moore has long been a booster for the music, whether hipping fans to key figures through interviews, articles, song titles and collaborations, or inviting the likes of New York Art Quartet, Wadada Leo Smith, David S. Ware and Descension to open for Sonic Youth. While not everyone was appreciative – back in 1996, Descension’s noisy improvised set nearly started a riot – many others came away with their minds blown. With his rock & roll attitude and openness to experimentation, Swedish saxophonist Gustafsson has been a major figure in leftfield music since the 1990s, while as a writer, poet, and label owner, Coley is a key node in connecting free jazz and underground rock.

Moore’s introduction to free jazz came in the 1980s, when Coley made him some cassettes of what he considered the essential jazz recordings. “He made me about 20 cassettes, and it was all the heavy hitters: Coltrane, Mingus, Miles, Dolphy,” Moore recalls. “There was some Sun Ra on there. And I was somewhat aware of Sun Ra, because he was an outsider that kind of transcended the jazz community into what was going on in the punk rock world. I really was studious listening to this music and being really curious about it, and it got me into reading all the literature I could find. It was John Litweiler’s The Freedom Principle book that really opened me up into European free improvisation, the world around FMP Records and Peter Brötzmann, and Incus Records with Derek Bailey. That side of the ocean created an identity of itself away from the typical model of what free jazz was coming out of the African-American culture, but always coexisting and being co-integrated with it.”

Moore was also attracted to the independent, artist-run nature of the music. “It wasn’t like punk rock started this business of having an alternate universe of recording. It was going on with these experimental jazz and improvisation musicians, and these labels, and it got me to wondering about who and what they were appealing to. It was appealing to me, just for the energy of it. There’s a certain bloody mindedness to a lot of it. But I realised that labels like Incus [in the UK], Po Torch [Germany/UK], Ictus in Italy, FMP in Germany and Instant Composers Pool in the Netherlands, in some ways, they were just creating missives from their localities to share with other localities, as opposed to trying to generate some response from the general listening public in the record store. They were just communicating with each other and sharing these ideas of improvisation as a dedicated vocation. I thought that was amazing because it reminded me of what I loved about the communitarianism of punk rock early on.”

The book comes illustrated with gems from the trio’s own record collection and gorgeous photographs of free jazz greats by Philippe Gras. Neneh Cherry provides a “foreverlogue”, testifying to the influence the music had on her growing up as the step-daughter of the peerless trumpeter-composer Don Cherry, while living legend Joe McPhee contributes an uproarious epilogue, “Fuck Free Jazz (In the voice of Samuel L. Jackson)… who started the rumour that jazz was free? Motherfucker! Musicians been payin’ for that shit since day one!” In addition to the list of 100 albums, the authors include a prologue with seven albums which answer the question, “What came before free jazz?” Plus there is a separate entry for Albert Ayler’s Spiritual Unity, a record that Moore considers the “holiest record… the be all and end all record for whatever our reasons are”.

Each of the texts for the 100 albums is written by Coley, Gustafsson or Moore (or sometimes all three), with their individual voices coming through. Their energy and enthusiasm are matched by their deep knowledge and insight. “We did intense research on these records. We really wanted to make sure that our data was correct,” says Moore. “It’s definitely a nerd Bible. Record nerds unite! We didn’t want it to be an academic tome. We wanted it to be joyful. We wanted to exemplify what the music meant to us, and it was this idea of excitement and joy and good energy, and also the mentality of the record collector as well. That’s what we wanted to share, more than anything.”

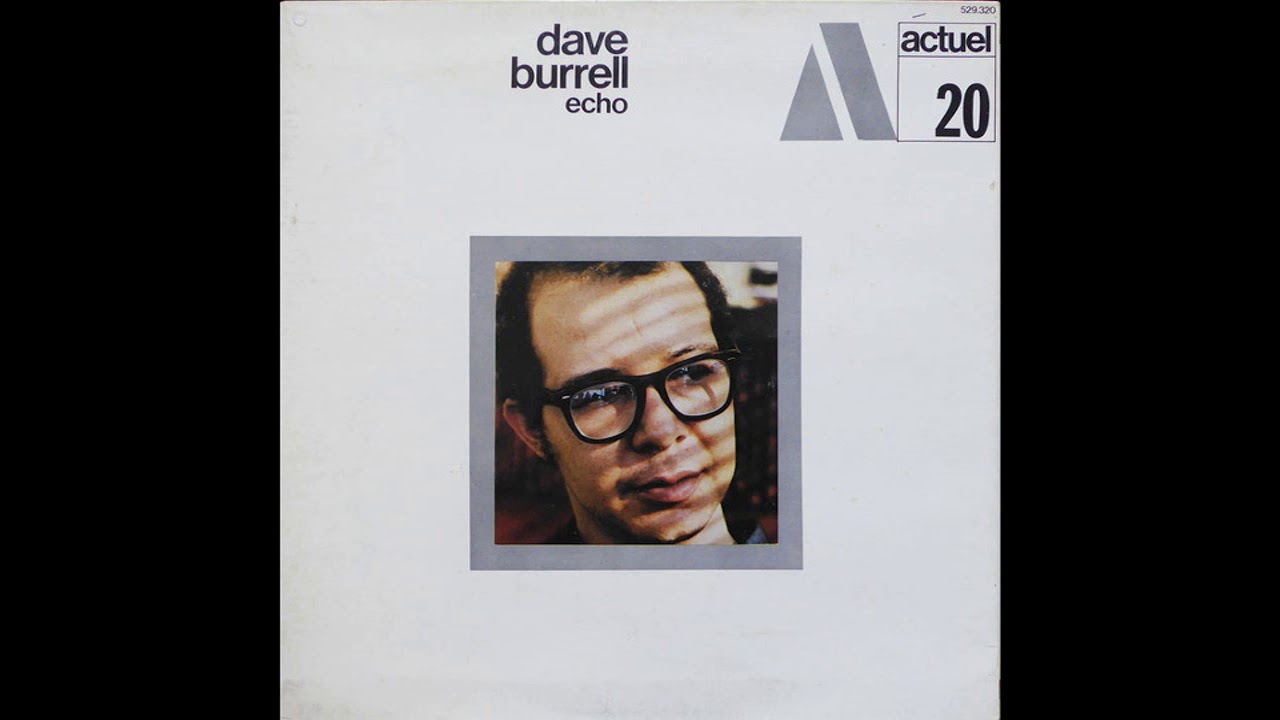

Dave Burrell – Echo (1969)

Pianist Dave Burrell reunites the all-star ensemble including Archie Shepp, Alan Silva and Sunny Murray, that he played with at the 1969 Pan-African Festival in Algiers for this monster session.

Thurston Moore: Dave Burrell’s Echo would be the first totally “free jazz” LP experience for my already noise-exposed ears and mind. Sometime in the late 80s/early 90s, when deciding to investigate this music further by working my way through the BYG catalogue, a label then focused on documenting the ex-pat free jazz community from North America (finding welcome arms in France) I was stunned to hear such unbridled ensemble playing where high energy spontaneous collective sound explosions defined the performance. Two pieces: ‘Echo’ on Side 1 which comes out of the gate like the flurry of an action painting and ‘Peace’ on Side 2 which is more languid and driven by roiling dark swoops and swathes all at full force. It was the gateway record where I knew I found a scene of greatness to be forever explored.

Spontaneous Music Ensemble – Karyobin Are The Imaginary Birds Said To Live In Paradise (1968)

A landmark in British free improvisation, Spontaneous Music Ensemble’s second album features the heavy lineup of John Stevens, Evan Parker, Kenny Wheeler, Derek Bailey and Dave Holland.

TM: A lot of it has to do with the fact of living in London and being really engaged with the history of free improvisation in London, especially the classic players such as Derek Bailey, Evan Parker and Maggie Nicols. I was already very interested in that when I was living in the States. So to be living in North London for ten years, where I was very close to Café Oto, which was the critical listening room for a lot of this music at that time, it allowed me to be in the same room with these people and then to play with a few of them. It really allowed me to be more intimate with that scene without it feeling like I was a rock & roller slumming in the free improv world or something. I never wanted to be that perception, or I tried not to conduct myself like that.

It was always about being non-hierarchical socially in that scene. And when that record came out, it came out on a major label. Free improvised music was usually issued on smaller labels, or even artist labels. To be on Island Records was quite something. Whoever shepherded that record into that label, were they thinking that they were going to crack the charts? It was recorded at Olympic Studios, a very professional studio, which was really interesting to me as you have this Jimi Hendrix adjunct going on as well. Maybe they thought if you’re interested in what Hendrix is doing, you’ll be really interested in what Derek Bailey is doing as a guitar player. I don’t know, but it’s a wonderful record. The fact that it was recorded at Olympic gives it this patina that most of these records do not have, because they’re recorded under much more financial constraint.

Alan Silva and the Celestial Communication Orchestra – Seasons (1970)

Epic triple album featuring a formidable ensemble of US, European and South African musicians associated with BYG records, including Dave Burrell, Michael Portal, Joachim Kuhn and the Art Ensemble Of Chicago.

TM: When I first got really obsessed with collecting free jazz records in the late 80s into the 90s, there were certain records that were really mythic… but I could never find Seasons by Alan Silva. It was a triple LP on BYG and was the hardest to locate, because it was probably the hardest one to distribute, because of its shipping weight. It was a huge orchestra of free jazz, free improv people led by Alan Silva, the great bassist who played with Albert Ayler on his on his European tours, had his own record on ESP disc. He was really a heavy figure. So, what could that record sound like? I just happened to be visiting relatives in southern Florida, and there was a used record store and one day, I guess early 90s, that triple album, was sitting in one of the bins. I couldn’t believe it. It’s a document of a live concert in Paris and it took three records to capture it. And it starts off with a slow build, and it just keeps developing and slowly morphing and ascending to the fourth side, where the grooves at the end of the fourth side can hardly contain the full cavalcade of sound and energy coming off the bandstand. It’s an incredible listen, because you think your stereo is going to crumble. So that validated everything that I was hoping this music would sound like.

Peter Brötzmann Octet – Machine Gun (1968)

This ferociously beautiful slab of European free jazz is an essential entry point for punk, metal and noise heads, capturing the revolutionary tumult of 1968.

TM: A lot of people were interested in Peter Brötzmann because of Caspar Brötzmann, his son, who [in the late 80s] was doing records that were more in tune with what bands like Sonic Youth, Swans, Einstürzende Neubauten were doing. In fact, Caspar Brötzmann Massaker, their very first gig was supporting Sonic Youth in Berlin. I bring that up because Peter Brötzmann’s Machine Gun was a record that you would hear about, it was a nuclear blast of a free improv record. The FMP label was not the easiest thing to find. The only way you could get the records was to order them from a small magazine called Cadence. They were the sole distributors of a lot of European free improvisation. It was a guessing game. You parse through the list and think God, that sounds interesting, but is it interesting? I just bought a handful, because I wasn’t willing [to hand] out that kind of money for a whole run of a label, but I did get Machine Gun, and I remember playing it, and it was kind of beyond my complacent ability to process what this music could possibly sound like in that context. If you know that record, it begins with Brötzmann playing tenor, as if it’s playing through the top of a snare head, this distorted rattle going on. It just comes banging out and then the percussion starts roiling on top and it’s this unstoppable freight train. That was my introduction to what’s going on in that world and there was no other record that was as high energy as that. But you kind of didn’t want anything more. It’s like, can we just take it down a notch and see what else is going on in this music?

Cecil Taylor – Akisakila (1973)

Pianist, composer and poet Cecil Taylor steers his Unit (saxophonist Jimmy Lyons and drummer Andrew Cyrille) way out on this stunning live recording.

TM: There’s so many incredible Cecil Taylor records that you can denote as being essential free jazz listening. The one we chose, Akisakila, it’s one of these records where I can experience the listening situation to like seeing Cecil Taylor live, where there’s so much information happening within a millisecond that your brain is not able to really process it in real time. I always found myself getting into this kind of narcotic state listening to Cecil Taylor, where I would just nod out. And it wasn’t out of boredom, that’s for sure. It was just out of complete mental exhaustion. This music would be in a flurry around your brain. I think if you were playing it, such as he was, you were fully engaged in it, like you were in a bicycle race, right? But to be sitting there and listening to it was really overwhelming. And I think that record really captures him in the heat of that. And it’s a beautiful looking record. It’s a Japanese gatefold, that has, if you’re lucky, this great, huge poster inside of it. I remember bringing that record back from when Sonic Youth was touring Japan. I found it in a record store and I brought it back to the USA, and I had this big pile of records that I was willing to trade. And Byron was going through them, and I was like, I might be willing to trade that Cecil Taylor record. And Byron was looking at it, and he pulled out the poster, and he was like, “did you know this was in there?” I was like, “No. In fact, thank you for showing me, that record is not for trade right now.” And then he was like, “I should have never pulled that poster out.” That’s how record nerds conduct business.

Archie Shepp – Blasé (1969)

A bluesy masterpiece from saxophonist Archie Shepp, with an unforgettable performance from the great vocalist Jeanne Lee on the title track.

TM: Archie Shepp’s Blasé was big for me. I was really interested in how he was incorporating more traditional big blues motifs into his playing as a jazz musician, and this idea of being untethered in the expression for your improvisation with jazz. He was a really important part of that story, coming out of Coltrane, and then getting into this territory of free playing. And then he would go back into investigating more traditional aspects of jazz music for a lot of his records in his later years. Blasé is from a live concert in France where it’s not exactly high energy free playing, but his sax playing, the way it’s recorded, it’s monstrous. In the title track, where it’s like a slow blues crawl, and then he introduces himself 30 seconds to a minute into the track with this intense honk and it’s shattering. And then you have this wonderful recitation by Jeanne Lee, who was singing free jazz and free improvisational, vocable stylings. Jeanne Lee is really important. There’s a Jeanne Lee record, Conspiracy, in the top 100 as well, that’s a really beautiful record. Her recitation on Blasé was just so heavy, you know, “blase, ain’t you, babe?” We talked to Neneh Cherry about this, because she said that was such an important record for her when she was growing up with Don and Moki Cherry in her house in Sweden.

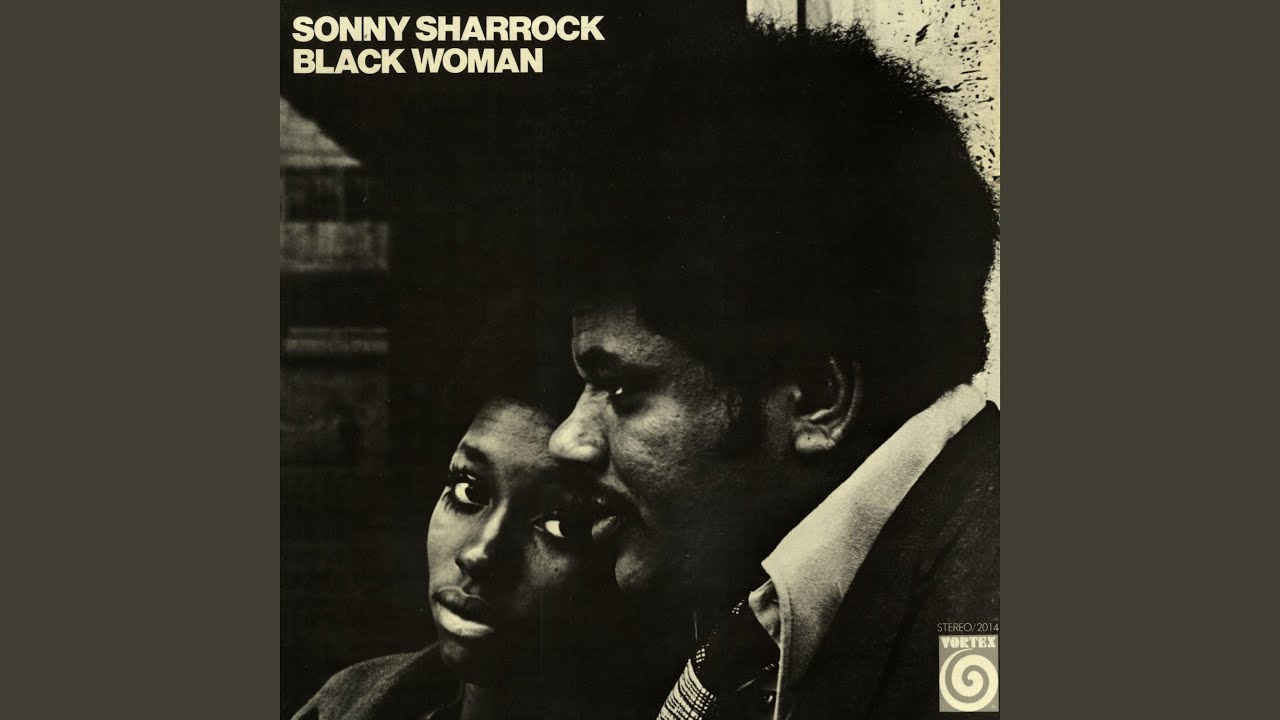

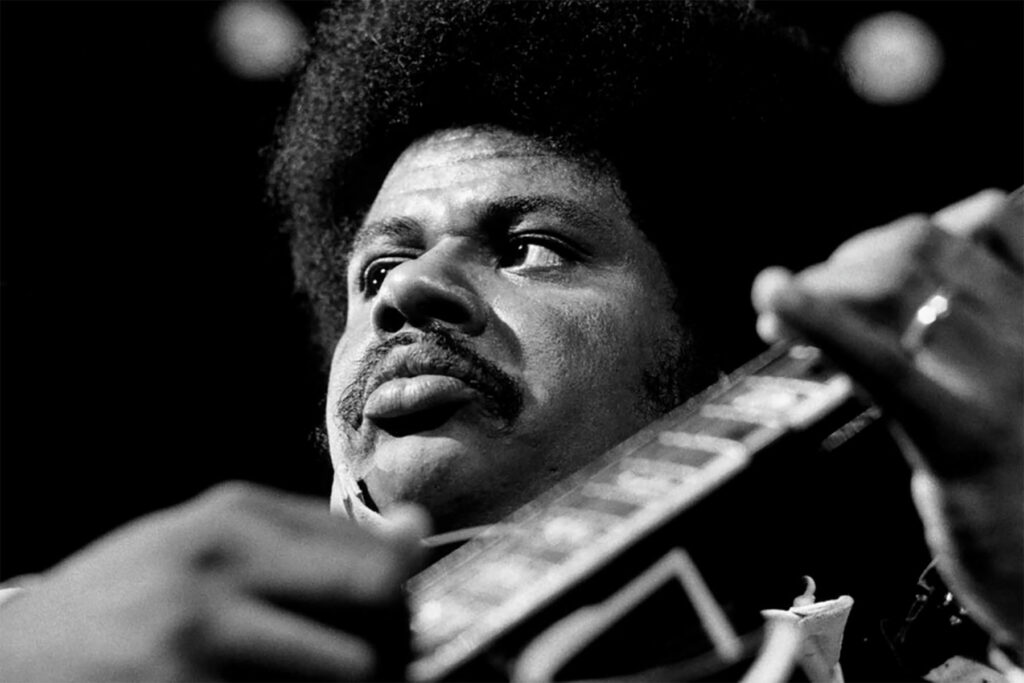

Sonny Sharrock – Black Woman (1969)

Guitarist Sonny Sharrock and vocalist Linda Sharrock wax ecstatic, channelling blues, raga, calypso and primal energies.

TM: The Sonny Sharrock record was this heavy document that you would know about, and to find it was almost impossible in the, 80s and 90s. I mean, it was probably in any cool record store in the 70s, but it was not a popular record, you know. It was kind of a jarring record to listen to, with Sonny’s guitar extrapolations and Linda Sharrock’s vocables, swooping – it was an intense record. There’s a Sonny Sharrock record on BYG called Monkey Pockey Boo. Again, finding that was near impossible. So, it was such an electric moment to find these records. It’s a beautiful looking record, I mean they’re just two stunning creatures with this beautiful, exalted yet calm visage. Really striking and really welcoming. And that music. it was heavy. You kind of knew about Sonny Sharrock from hearing him on Pharaoh Sanders’ Tauhid record: how much more of this guy can there be? Where is it? And you knew that he was on these Herbie Mann records, and there’d be these little instances of his breaking out on there. A lot of people claim I made this cassette of just the extrapolations of Sonny Sharrock’s playing on all the Herbie Mann records, sort of like the Dean Benedetti Charlie Parker recordings, where he just recorded the solos. I was doing that with Sonny Sharrock. I was like, maybe I did, my memory doesn’t serve me so well. I certainly talked about it.

Patty Waters – The College Tour (1966)

An avant-garde vocal classic, inspiring the likes of Yoko Ono and Diamanda Galas. Waters abstracts jazz standards and folk songs through sensuous, swooping and cathartic extended technique.

TM: I’m not sure where I first heard about Patty Waters, but I think it might have been through Lydia Lunch, who would mention how Patty Waters was somebody that she based her singing style on. She said, you ever heard ‘Black Is The Color Of My True Love’s Hair’ [from Patty Waters Sings, 1966]? It’s kind of blood curdling, the way she goes off with this really plaintive, kind of icy, stretching out on the notes and breaking them down into this really focused discord. And then coming across The College Tour in the nether regions of some record store, wow! It had this black and white photo of this woman with the ashes on her forehead. It’s a Catholic school rite of passage; you go and get the ashes on your forehead on Ash Wednesday every year. And the fact that that was her photo on the front, it was somewhat startling and audacious, because there was something very sacred in that Christian ritual. And here she was, putting it on a record cover. She looked very strange, so what could that record sound like? And the record was extremely strange sounding. It was a toss-up between Patty Waters Sings and The College Tour. We chose The College Tour because it’s more consistent with her expression, free jazz and free improv. With a lot of these records, we mentioned adjunct records by the artist within the text.

William Breuker, Han Bennink – New Acoustic Swing Duo (1967)

The first release on the Instant Composers’ Pool label, this is an explosive early document of the Dutch scene, with Breuker tearing it up across several reeds while Bennink lets loose on an array of percussion.

TM: This album is really important, because it really works as an, ‘Oh, if they turn you off are you still there? No, I’m here.’ It’s an artist production, to the point where Han Bennink took it upon himself to illustrate each and every cover. The record would eventually be reissued with a generic cover, but when they first released it, Bennink adorned each cover with his pencil illustrations, because he’s a visual artist, as well as being a recognized free improvisor/drummer. His pedigree was pretty amazing, playing on Eric Dolphy’s Last Date and such. And the music is this very descriptive exponent of what was happening in the free improvised music scene in The Netherlands.

There was a sense of play there that you might not find so much in the other scenes, whether it’s the UK or Germany or Italy or France, this aspect of humour, all the while, people playing with this somewhat high technique. They were obviously very accomplished players in any traditional mode. And the fact that they were lending that that technique to this utterly free music that was really based on the mechanisms of response and in mutuality, that was really exciting. And the fact that they were keeping it “real” by saying, ‘We’re just going to make these homemade covers, and if you’re at the gig, you can buy one.’ You can’t even be a completist of that record, because you’d have to have every single copy manufactured. Mats has quite a few copies of that record. We have nine of them in the book on one page. I think those are all Mats’ copies. Almost every single record in the book is from Mats’ archive, because a lot of my holdings are still in the USA, Byron’s stuff is everywhere. Mats has a really dedicated man cave of a record room where he lives, so he was the only one who was able to pull these things out and scan them correctly. You can see the creases and the wear, and the time spent handling these records, which I think added to the aesthetic of the book, because we didn’t really want to have everything pristine. Records are used and you want them to be used.

Feminist Improvising Group – Feminist Improvising Group (1979)

Formed in 1977, FIG was a collective project whose core members were Maggie Nicols, Lindsay Cooper, Irene Schweizer, George Born and Sally Potter. They sought to challenge male dominance in free improvisation, including theatrical and satirical elements in their performances.

TM: This is the only cassette in the book. That was a very essential release. We were very concerned about having as much presence for female musicians. The Feminist Improvising Group cassette was something that we knew we wanted to put in there because of, because of what it denoted at the time, which was a group of women coming together to have a free improvising ensemble in the face of such a male-centric world of music, and to present itself without any kowtowing to the [established] model of improvising ensembles and really expressing their concerns in feminism through this. It’s a fascinating document. It’s a cassette of various live events that they had. They ran up against a lot of naysayers in the scene like, ‘that music really breaks from the tradition of what we’re doing.’ And no, it actually really furthers the tradition of this music. So, it really calls out these boneheaded takes.

Calling itself the Feminist Improvising Group, there’s something so pure about it, because they had no moniker for themselves. They were a group of women who decided to have an improvising ensemble and end of story, it’s like, why can’t we just be nameless. I think it was a promoter, as legend has it, that wrote, it’s a feminist improvising group, you know. And so, when they played that first concert, they were like, well, we didn’t name ourselves, that it’s just a descriptor, and they really have anything against it. They were refuting any kind of label for what they were, who they were, what they were – there’s nothing much more free than that.

Now Jazz Now100 Essential Free Jazz & Improvisation Recordings 1960-80 is out now via Ecstatic Peace

![Alan Silva and the Celestial Communication Orchestra - Seasons [full album]](https://thequietus.com/app/cache/flying-press/fb27096564884d8e0ba1170b8f598c74.jpg)